Learning from the Experience of Others a Selection of Case Studies About Siting Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Integrated Solid Waste Resource Management ("TIRM") Process - Request for Proposals for Disposal Services

Toronto Integrated Solid Waste Resource Management ("TIRM") Process - Request for Proposals for Disposal Services (City Council on June 7, 8 and 9, 2000, amended this Clause by deleting from the recommendation of the Works Committee, after the words “Emergency Services”, the words “a verifiable environmental”, and inserting in lieu thereof the words “an environmental”, and adding to such recommendation the words “verifiable to the satisfaction of the Commissioner of Works and Emergency Services”, so that the recommendation of the Works Committee shall now read as follows: “The Works Committee recommends that TIRM Respondents offering disposal services be required to have in place at the time of contract implementation, or an implementation schedule acceptable to the Commissioner of Works and Emergency Services, an environmental management system for their disposal, operations and applicable transportation systems, verifiable to the satisfaction of the Commissioner of Works and Emergency Services.”) The Works Committee recommends that TIRM Respondents offering disposal services be required to have in place at the time of contract implementation, or an implementation schedule acceptable to the Commissioner of Works and Emergency Services, a verifiable environmental management system for their disposal, operations and applicable transportation systems. The Works Committee reports, for the information of Council, having received presentations by the following Respondents to the TIRM Request for Proposals for Disposal Services: - Essex-Windsor Solid Waste Authority, represented by: - Mr. Todd R. Pepper, General Manager, Essex-Windsor Solid Waste Authority. (A copy of the aforementioned presentation was submitted to the Committee.) - Green Lane Landfill, represented by: - Ms. Anne Hiscock, Green Lane Landfill. (A copy of the aforementioned presentation was submitted to the Committee.) - Onyx North America Corporation (formerly Browning Ferris Industries), represented by: - Mr. -

Canadian-American Environmental Relations: a Case Study of the Ontario-Michigan Municipal Solid Waste Dispute

Canadian-American Environmental Relations: A Case Study of the Ontario-Michigan Municipal Solid Waste Dispute by Taylor Ann Heins A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies in Environment and Resource Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2007 ©Taylor A. Heins 2007 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Canada and the United States are faced with many cross-border environmental issues and therefore must negotiate potential solutions with one another. Complicating such negotiations is the fact that both countries are federal systems which require negotiations and decision-making interactions amongst various levels of government domestically which, in turn, influence and are influenced by bilateral relations. Therefore, this study focuses on governmental relations both within each country (intergovernmental relations) and between the two countries (bilateral/international relations). Using the Ontario-Michigan Municipal Solid Waste dispute (1996-2006) as a case study, this thesis advances an organizational framework for the examination of the role of formal and informal interactions in shaping bilateral environmental policy. Through application of this framework, it is revealed that both formal and informal federal level relations in the U.S. prevented sub-national and local level authorities from effectively developing a solution to the dispute. Future studies which apply the organizational framework used in this thesis to other cross-border environmental issues are needed in order to determine whether such conclusions hold true in the case of all cross border disputes. -

Lesson's Learned

What’s Up Up North!!! Lesson’s Learned Sustainable Integrated Solid Waste Resource Management in Canada in the 21st Century © 2014 HDR, all rights reserved. Background Key Projects Key Lessons Learned Summary BACKGROUND BY THE NUMBERS Population: ~35 million (1/10 the US) about approximately the size of California Landmass: ~ 9.9 M sq km (slightly larger than the US) 13 Provinces and Territories Approximately 90% of the population is concentrated within 160 km (100 mi) of the US border Generates ~ 25 million tonnes per year ( ~ 27 M tons) WASTE MANAGEMENT IN CANADA KEY CANADIAN PROJECTS KEY PROJECTS City of Toronto Regions of Durham/ York City of Edmonton Southern Alberta Energy from Waste Alliance City of Surrey This image cannot currently be displayed. CITY OF TORONTO Over 4 million inhabitants Generates over 1,000,000 tonnes per year Separate collection of Recyclables and Organics Key City Owned Facilities: o Dufferin Creek AD Plant – 27,500 tons per year o Disco Road AD Plant – 83,000 tons per year o Green Lane Landfill (out-of-City) – capacity to 2040 TORONTO’S WASTE STRATEGY VISION Reduce the amount of waste generated, reuse what they can, and recycle and recover the remaining resources to reinvest back into the economy. Embrace a waste management system that is user friendly with programs and facilities that balance the needs of the community and environment with long term financial sustainability. Ensure a safe, clean, beautiful and healthy City for the future. EVALUATING LONG TERM OPTIONS EVOLUTION OF WASTE MANAGEMENT IN DURHAM REGION Durham Region was established in 1974. -

Statement of Claim, As Required by the Proceedings Against the Crown Act

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats by contacting us. Contenu archivé L'information archivée sur le Web est disponible à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de dossiers seulement. Elle n’a été ni modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date d’archivage. Les pages archivées sur le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez obtenir cette information dans un format de rechange en communiquant avec nous. UNDER THE UNCITRAL ARBITRATION RULES AND SECTION B OF CHAPTER Ii OF TIlE NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN: VITO G. GALLO Investor v GOVERNMENT OF CANADA (“Canada”) Party STATEMENT OF CLAIM A. NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE PARTIES CLAIMANT! INVESTOR: Vito G. GallooAc) ENTERPRISE: 1532382 Ontario Inc. 225 Duncan Mill Road Suite 101 Don Mills, Ontario M3B 3K9 Canada PARTY: GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Office of the Deputy Attorney General of Canada Justice Building 239 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario KIA 0H8 Canada 1. The Investor alleges that the Government of Canada has breached, and continues to breach, its obligations under Chapter 11 of the NAFTA, including, but not limited to: (i) Article 1105, The Minimum Standard of Treatment (ii) Article 111 0, Expropriation and Compensation 2. -

Claimant Post-Hearing Submission (Redacted)

UNDER THE UNCITRAL ARBITRATION RULES AND SECTION B OF CHAPTER 11 THE NORTH AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN: VITO GALLO Claimant /Investor v. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA ("Canada") Respondent/Party CLAIMANT'S POST -HEARING BRIEF RE: OWNERSHIP OF THE INVESTMENT REDACTED April8, 2011 BENNETT GASTLE Professional Corporation Lawyers 36 Toronto Street, Suite 250 Toronto, ON M5C 2C5 Charles M. Gastle Tel: 416.361.3319ext.222 Fax: 416.361.1530 MURDOCH R. MARTYN Barrister and Solicitor 33 Hazelton Avenue, Suite 94 r.rr.nTr- ON M5R 2E3 the Investor Tel: 416.433.2890 Fax: 416.964.2328 Of counsel, TODD WEILER UNDER THE UNCITRAL ARBITRATION RULES AND SECTION B OF CHAPTER 11 OF THE NORTH AMERICAN AGREEMENT BETWEEN: VITO G. GALLO Investor V. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA ("Canada") Party CLAIMANT'S POST -HEARING BRIEF 1. The issue before the Tribunal is whether Mr. Vito Gallo ("Gallo") owned or controlled 1532382 Ontario Inc. (the "Enterprise") prior to the introduction of the Adams Mine Lake Act ("AMLA") into the Ontario legislature on April 51h, 2004. The Claimant met his burden of proof by placing the Enterprise's Minute Book into the evidentiary record and by proving how Ontario law the applicable law under NAFTA Article 11 17 - recognizes that Gallo has controlled the Enterprise since its incorporation in 2002. The Minute Book contained both the original shareholders' register and the original share certificates. None of the evidence adduced at the hearing suggested otherwise. Instead, the forensic evidence and the viva voce evidence support and verify the authenticity of the documents. no answer this prima claim. All of hopes were tests, the of which only strengthened the Claimant's prima facie case. -

ARV79: Annual Report, Mining Operations, 1969

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

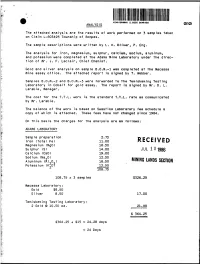

Bompass Twp Prop

42Aeiswe*ei 2.9235 BOMPASS 010 ANALYSIS The attached analysis are the results of work performed on 1 samples taken on Claim L-803495 Township of Bompas. The sample descriptions were written by L. K. O liver, P. Eng. The analysis for iron, magnesium, sulphur, calcium, sodium, aluminum, and potassium were completed at the Adams Wine Laboratory under the direc tion of Mr. J. F. Leclair, Chief Chemist. Gold and silver analysis on sample 8.0.M.-l was completed at the Macassa Wine assay office. The attached report is signed by T. Webber. Samples B.O.M.-2 and B.O.M.-3 were forwarded to the Temiskaming Testing Laboratory in Cobalt for gold assay. The report is signed by Mr. D. L. Larabie, Manager. The cost for the T.T.L. work is the standard T.T.L. rate as communicated by Mr. Larabie. The balance of the work is based on Swastika Laboratory fee schedule a copy of which is attached. These fees have not changed since 1984. On this basis the charges for the analysis are as follows: ADAMS LABORATORY Sample preparation 2.75 D C f C 11/C rx Iron (total Fe) 11.00 K t L 11 V C D Magnesium (MgO) 18.50 sulphur is) u.oo JUL 1 01986 Calcium !CaO) 19.00 Sodium (Na^O) 12.50 Aluminum Slip.),,,..~, le.©so MINING LANDS SECTION Potassium (K^OT 12.50 108.75 108.75 x 3 samples 1326.25 Macassa Laboratory: Gold S8.50 Silver 8.50 17.00 Temiskaming Testing Laboratory: 2 Gold @ 10.50 ea. -

Under the Uncitral Arbitration

UNDER THE UNCITRAL ARBITRATION RULES AND SECTION B OF CHAPTER Ii OF TIlE NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN: VITO G. GALLO Investor v GOVERNMENT OF CANADA (“Canada”) Party STATEMENT OF CLAIM A. NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE PARTIES CLAIMANT! INVESTOR: Vito G. GallooAc) ENTERPRISE: 1532382 Ontario Inc. 225 Duncan Mill Road Suite 101 Don Mills, Ontario M3B 3K9 Canada PARTY: GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Office of the Deputy Attorney General of Canada Justice Building 239 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario KIA 0H8 Canada 1. The Investor alleges that the Government of Canada has breached, and continues to breach, its obligations under Chapter 11 of the NAFTA, including, but not limited to: (i) Article 1105, The Minimum Standard of Treatment (ii) Article 111 0, Expropriation and Compensation 2. The relevant portions of the NAFTA are attached as “Appendix ‘A” hereto. B. FACTS SUPPORTING THE CLAIM B. I IDENTITY OF THE cLAIMANT, THE INVESTMENT, AND THE ENTERPRISE 3. This claim is brought on behalf of 1532382 Ontario Inc. (“the Enterprise”). The Enterprise was incorporated under the laws of Ontario on June 26, 2002.1 4. The Enterprise owns and controls what had been a licensed waste site whose lands included a former iron ore mine located in Northern Ontario, known as the Adams Mine Site 2. Adams Mine Site is approximately 10 kilornetres south-east of the (“the Investment”)3The town of Kirkland Lake. 4 5. The Investor, Mr. Vito Gallo, is a national of the United States, resident in Pennsylvania. 6. Mr. Brent Swanick is the President and sole director of the Enterprise. -

Resources – Not Garbage Municipal Solid Waste in Ontario

RESOURCES – NOT GARBAGE MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE IN ONTARIO By John Jackson Prepared for The Environmental Agenda for Ontario Project March 1999 SUMMARY Current Status In 1996, almost 9 million tonnes of municipal solid wastes were generated in Ontario. This amount was almost identical to the amount of wastes generated in 1987, almost ten years earlier. Approximately 80% of the waste generated was dumped into landfills in 1996. As of 1996, garbage disposal had been reduced by 22% from 8.9 million tonnes in 1987 to seven million tonnes in 1996. This means that four years after the provincially-set 1992 interim target date, we still have not met the interim target of 25% reduction. This makes it very unlikely that the target of 50% reduction by 2000 will be achieved. Disposal of garbage from residences has increased by 2.6% between 1987 and 1996. Disposal from the industrial, commercial and institutional sectors has decreased by 60%. This failure to reduce wastes generated and disposed of results in: wasted valuable resources, increased energy use, increased contamination at both the production and disposal stages, increased use of water at the production stage, increased climate change because of the release of methane by decomposing garbage, and the release of toxic contaminants from waste disposal facilities to the air and to surface and ground waters. The failure to reduce garbage generation and disposal to a greater extent has resulted in proposals for the expansions of many landfills across the province and for the creation of new mega-sites such as the Adams Mine in northern Ontario. -

Adams 20Mine 20Decision

EAB Decision: Notre Development Corporation EA-97-01 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT BOARD EA-97-01 Notre Development Corporation (Adams Mine Site) Decision and Reasons for Decision In the matter of an application submitted by Notre Development Corporation for the development and operation of the South Pit of the Adams Mine as a Landfill located in Boston Township, south east of the Town of Kirkland Lake; And in the matter of the questions concerning the proposed “hydraulic containment” design, as referred to the Board by the Minister of the Environment, pursuant to Section 9.2 of the Environmental Assessment Act; And in the matter of the Environmental Assessment Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.E- 18, as amended. Before: Len Gertler - Chair Pauline Browes - Member Don Smith - Member (Dissenting) Dated at Toronto this 19th Day of June, 1998. 2300 Yonge Street Suite 1201 Toronto, Ontario M4P 1E4 Tel: (416) 314-4600 Table of Contents EAB Decision: Notre Development Corporation EA-97-01 Appearances ............................................................1 Participants .............................................................1 Witnesses ..............................................................2 The Decision ............................................................3 Reasons for Decision .....................................................4 1. Introduction .......................................................4 1.1 The Application and the Minister’s Referral .........................4 1.2 The Hearing Process ...........................................7 -

Northeastern Ontario Faces Threat of Adams Mine Dump ... Again

Northeastern Ontario Faces Threat of Adams Mine Dump ... Again A highly controversial proposal to ship Toronto's garbage 8 hours north for dumping in an abandoned open pit mine has been pushed back into the limelight, amid a rash of controversies and charges of unfair dealing. Secret land deals, million dollar political donations and interference from the highest level of government have all been part of the picture as garbage entrepreneur and recently convicted tax evader Gordon McGuinty of Notre Development tries once again to lure Toronto trash away from the waste company currently contracted to ship the municipality's solid waste to private landfills in Michigan. When the City of Toronto walked away from the deal in the fall of 2000 because of liability concerns, local residents breathed a sigh of relief, after having fought the deal for more than decade. But accounts of meetings in February between Notre Development and CN Rail to map out a strategy to foment discontent over Toronto's shipping of garbage to Michigan signaled an end to that respite. In the intervening months tension has steadily built, as local activists and politicians drew the connecting lines between several powerful new players backing the most recent version of the Adams Mine deal. New on the scene is Mario Cortellucci, a multi-millionaire land developer in the Toronto region. Cortellucci is also the new owner of the Adams Mine, and the single largest donor to the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party, having donated over a million dollars since the Conservatives came to power in 1995. One of the issues at the heart of the current controversy is a land deal which would see the Province of Ontario sell Cortellucci 2,000 acres of land surrounding the mine pits - the land acquisition is key to the project going ahead - for just $22 per acre. -

Redacted Version

IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER CHAPTER ELEVEN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT and THE UNCITRAL ARBITRATION RULES between VITO G. GALLO (Claimant) and THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA (Respondent) AWARD ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL Professor Juan Fermindez-Armesto (President) Professor Jean-Gabriel Castel, OC, Q.C. Dr. Laurent Levy Secretary to the Tribunal: Mrs. Deva Villanua Gomez Registry: Permanent Court of Arbitration (Mr. Martin Doe) Gallo v. Canada Page 2 of73 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE PARTIES 4 II. THE TRIBUNAL 5 III. PROCEDURAL HISTORY 6 IV. INTRODUCTION 18 v. POSITION OF THE PARTIES 19 1. The Claimant's case 19 2. The Respondent's case 22 VI. FACTS 25 1. Dramatis Res et Personae 25 2. The purchase of the Adams Mine 26 3. Incorporation of the Enterprise 30 4. The Limited Partnership and related Agreements 41 5. Management of the Enterprise and of the Adams Mine 43 6. Tax returns of Mr. Gallo and of the Enterprise 45 7. Mr. Gallo's activities in the US 46 8. Efforts to resell the Adams Mine: the li{jg Agreement 47 9. Enactment of the AMLA 50 VII. ASSESSMENT OF EVIDENCE 53 1. Introduction: The burden of proof 53 2. Weighing of Evidence regarding the Factual Record 53 PCA 55798- NAFTA Gallo v Canada Gallo v. Canada Page 3 of73 VIII. LEGAL ANALYSIS 62 I. Introduction 62 2. Lack of Jurisdiction Ratione Temporis 63 IX. CONCLUSION 66 X. COSTS 69 I. The Costs of Arbitration 70 2. The Costs of Legal Representation and Assistance 71 XI. DECISION 72 PCA 55798 - NAFTA Gallo v Canada Gallo v.