The Afghan Wars, 1839-42 and 1878-80 (1892)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US, Missile Defence and the Iran Threat

IDSA Monograph Series No. 9 December 2012 In Pursuit of a Shield: US, Missile Defence and the Iran Threat S. Samuel C. Rajiv US, MISSILE DEFENCE AND THE IRAN THREAT | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 9 December 2012 In Pursuit of a Shield: US, Missile Defence and the Iran Threat S. Samuel C. Rajiv 2 | IDSA MONOGRAPH SERIES Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-08-6 Disclaimer: It is certified that views expressed and suggestions made in this Monograph have been made by the author in his personal capacity and do not have any official endorsement. First Published: December 2012 Price: Rs. 299/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Cover & Layout by: Geeta Kumari Printed by: Omega Offset 83, DSIDC Complex, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase I New Delhi-110 020 Mob. 8826709969, 8802887604 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.omegaoffset.co.nr US, MISSILE DEFENCE AND THE IRAN THREAT | 3 Contents Acknolwedgement.......................................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................7 II. US AND IRAN: THREE DECADES OF CONTENTIOUS RELATIONS..................................................10 III. US STRATEGIC ASSESSMENTS AND IRAN.....................16 Missile Threat Nuclear Threat IV. -

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

List of Signatories Family Members of the Victims and Former Political

List of Signatories Family Members of the Victims and Former Political Prisoners 1 Abani, Ali Former Political Prisoner, Political Activist and University Professor 2 Alavi, Dr. Hossain Physician and brother of the victim Mehdi Alavi Shushtari 3 Alavi, Edina M. Family member of the victim Mehdi Alavi Shushtari 4 Alavi, Laleh Sister of the victim Mehdi Alavi Shushtari 5 Alavi, Mark M. Brother of the victim Mehdi Alavi Shushtari 6 Alavi, Ramin Nephew of the victims Mehdi Alavi Shushtari 7 Alizadeh, Solmaz Daughter of the victim Mahmoud Alizadeh 8 Bakian, Hasti Niece of the victim Bijan Bazargan 9 Bakian, Kayhan Nephew of the victim Bijan Bazargan 10 BaniAsad, Hanna Niece of the victim Bijan Bazargan 11 BaniAsad, Leila Niece of the victim Bijan Bazargan 12 Bazargan, Babak Brother of the victim Bijan Bazargan 13 Bazargan, Banafsheh Sister of the victim Bijan Bazargan 14 Bazargan, Dr. Niloofar Physician and sister of the victim Bijan Bazargan 15 Bazargan, Laleh Sister of the victim Bijan Bazargan 16 Bazargan, Lawdan Former Political Prisoner & Sister of the victim Bijan Bazargan & Political & Human Rights Activist 17 Behkish, Mansureh Former Political Prisoner & Sister of the Victims Zahra Behkish, Mohammad Reza Behkish, Mohsen Behkish, Mohammad Ali Behkish, Mahmoud Behkish and Sister- in-Law of victim Siamak Asadian 18 Boroumand, Dr. Ladan Co-founder of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation; Daughter of the Victim Abdorrahman Boroumand 19 Boroumand, Dr. Roya Executive Director of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation; Daughter of the Victim Abdorrahman Boroumand 20 Damavandi, Ali Brother of the victim Mohammad Seyed Mohesen Damavandi 21 Damghani, Saman Family Member of one of the Victims of 1988 22 Ebrahim Zadeh, Bagher Brother of the victim Dr. -

Resettlement Policy Framework

Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) Project (Component II- Economic Corridor Development) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Peshawar Public Disclosure Authorized March 2020 RPF for Khyber Pass Economic Corridor Project (Component II) List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected household AI Access to Information APA Assistant Political Agent ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan BHU Basic Health Unit BIZ Bara Industrial Zone C&W Communication and Works (Department) CAREC Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation CAS Compulsory acquisition surcharge CBN Cost of Basic Needs CBO Community based organization CETP Combined Effluent Treatment Plant CoI Corridor of Influence CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor CR Complaint register DPD Deputy Project Director EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency ERRP Emergency Road Recovery Project ERRRP Emergency Rural Road Recovery Project ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FBR Federal Bureau of Revenue FCR Frontier Crimes Regulations FDA FATA Development Authority FIDIC International Federation of Consulting Engineers FUCP FATA Urban Centers Project FR Frontier Region GeoLoMaP Geo-Referenced Local Master Plan GoKP Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa GM General Manager GoP Government of Pakistan GRC Grievances Redressal Committee GRM Grievances Redressal Mechanism IDP Internally displaced people IMA Independent Monitoring Agency -

Vol 66 No 3: September 2014

www.gurkhabde.com/publication The magazine for Gurkha Soldiers and their Families PARBVolAT 66 No 3: SeptemberE 2014 Gurkha permanent staff with the World Marathon Champion Mr Kiprotich during the Bupa Great North Run 2014 ii PARBATE Vol 66 No 3 September 2014 PARBATE ENTERING A MODERN ERA HQ Bde of Gurkhas, FASC, Sandhurst, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ. All enquiries Tel: 01276412614 / 94261 2614 Fax: 0127641 2694 / 94261 2694 Email: [email protected] Editor Cpl Sagar Sherchan 0127641 2614 [email protected] Comms Officer Cpl Sagar Sherchan GSPS Mr Ken Pike 0127641 2776 [email protected] elcomeelcome to to a a brand brand new new edition edition with with lots lots of of changes changes Please send your articles together with high WWinin terms terms of of the the outline outline and and design. design. Lots Lots of of attractive attractive quality photographs (min 300dpi), through your unit’s Parbate Rep, to: subjectssubjects and and some some great great photographs photographs from from around around the the globe globe The Editor, Parbate Office, awaitawait our our readers. readers. HQBG, FASC, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ AsA soperations operations in in Afghanistan Afghanistan gradually gradually wind wind down, down, Parbate is published every month by kind permission soldierssoldiers from from 1 1 RGR RGR settled settled in in Brunei Brunei focusing focusing on on getting getting of HQBG. It is not an official publication and the views expressed, unless specifically stated otherwise, do backback the the basics basics right right (page (page 2). 2). not reflect MOD or Army policy and are the personal views of the author. -

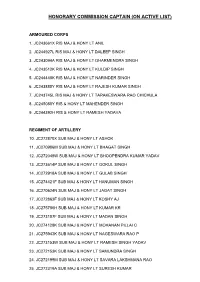

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Reconstructing Our Understanding of the Link Between Services and State Legitimacy Working Paper 87

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Reconstructing our understanding of the link between services and state legitimacy Working Paper 87 Aoife McCullough, with Antoine Lacroix and Gemma Hennessey June 2020 Written by Aoife McCullough, with Antoine Lacroix and Gemma Hennessey SLRC publications present information, analysis and key policy recommendations on issues relating to livelihoods, basic services and social protection in conflict affected situations. This and other SLRC publications are available from www.securelivelihoods.org. Funded by UK aid from the UK Government, Irish Aid and the EC. Disclaimer: The views presented in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies or represent the views of Irish Aid, the EC, SLRC or our partners. ©SLRC 2020. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from SLRC for their own publications. As copyright holder SLRC requests due acknowledgement. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Overseas Development Institute (ODI) 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 3817 0031 F +44 (0)20 7922 0399 E [email protected] www.securelivelihoods.org @SLRCtweet Cover photo: DFID/Russell Watkins. A doctor with the International Medical Corps examines a patient at a mobile health clinic in Pakistan. B About us The Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) is a global research programme exploring basic services, and social protection in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Funded by UK Aid from the UK Government (DFID), with complementary funding from Irish Aid and the European Commission (EC), SLRC was established in 2011 with the aim of strengthening the evidence base and informing policy and practice around livelihoods and services in conflict. -

The Khyber Pass the Khyber Pass Is a Narrow, Steep-Sided Pass That Connects Northern Pakistan with Afghanistan

Name ___________________ Date ____ Class _____ Physical Geography of South Asia DiHerentiated Instrudion The Khyber Pass The Khyber Pass is a narrow, steep-sided pass that connects northern Pakistan with Afghanistan. (A pass is a lower point that allows easier access through a mountain range.) The Khyber Pass winds for about 30 miles (48 km) through the Safed Koh Mountains, which are part of the Hindu Kush range on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Roads through the pass link the cities of Peshawar, Pakistan, . and Kabul, Afghanistan. Because of its strategic location, the Khyber Pass has been a vital trade-and invasion-route from Central Asia to South Asia for centuries. About 326 B.C., Alexander the Great moved his troops through the pass on the way to India. British and Indian forces used it as an entry point for their invasions of Afghanistan during the three Afghan Wars (the last occurring in 1919). Some historians have even theorized that the Aryan people originally migrated to India by going through the Khyber Pass. Today two highways snake through the Khyber Pass-one for vehicles and the other for traditional camel caravans. A railway line also winds through the pass. Recently, the Khyber Pass has been used by refugees from the Afghanistan civil war to get into Pakistan, and by arms dealers transporting weapons into Afghanistan. The people who live in the villages along the Khyber Pass are mainly ethnic Pashtuns. During the Afghan-Soviet War (1979-1989), Pashtuns were important members of the mujahideen. These are Islamic guerrilla groups that fought the Soviets during their takeover of Afghanistan. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

18Cboes of Tbe Lpast.'

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-59-03-08 on 1 September 1932. Downloaded from G. A. Kempthorne 217 effect of albumin is rememberep.. 'l'hus, where a complete method of steam sterilization by downward displacement cannot be used, the method of first washing in hot water, and then leaving the utensils to stand in ' potassium permanganate 1 in 1000 solution is recommended. Irieffective methods of sterilization are dangerous, in that they give a false sense of security. A,considerable number of experiments were done in the Pat-hological Department of Trinity College, Dublin; and my thanks are due to Professor J. W. Bigger, who gave me the facilities for carrying them out, and for many helpful suggestions. I should also like to thank Dr. G. C. Dockery and Dr. L. L. Griffiths for their advice.. and help . 18cboes of tbe lPast.' THE SECOND AFGHAN WAR., 1878-1879. guest. Protected by copyright. By LIEUTENANT·COLONEL G. A. KEMPTHORNE, D.S.O., Royal Army Medical Corps (R.P.). THE immediate cause of the Afghan Wars ofl878-1880 was the reception of a Russian Mission at Kabul and the refusal of the AmiI', Shere Ali, to admit a British one. War was declared in November, 1878, when three columns crossed into Afghanistan by way of the Khyber, the Kuram Valley, and the Khojak Pass respectively. The first column consisted of 10,000 British and Indian troops under Sir Samuel Browne, forming a division; the Kuram force, under Sir Frederick Roberts, was 5,500 strong; Sir Donald Stewart, operating through Quetta, bad a division equal to tbe first. -

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism Mohammad Rezaie Yazdi A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Political Science and International Studies University of Birmingham March 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran was based and formed upon the concept of Khomeinism, the religious, political, and social ideas of Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini. While the Iranian revolution was carried out with the slogans of independence, freedom, and Islamic Republic, Khomeini's framework gave it a specific impetus for the unity of people, religious culture, and leadership. Khomeinism was not just an effort, on a religious basis, to alter a national system. It included and was dependent upon the projection of a clash beyond a “national” struggle, including was a clash of ideology with that associated with the United States. Analysing the Iran-US relationship over the past century and Khomeini’s interpretation of it, this thesis attempts to show how the Ayatullah projected "America" versus Iranian national freedom and religious pride.