Download 1 File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO ME WITHOUT YOU Thesis Submitted to the College of Arts

NO ME WITHOUT YOU Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English By Sandra E. Riley, M.Ed UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2017 NO ME WITHOUT YOU Name: Riley, Sandra Elizabeth APPROVED BY: ____________________________________ PJ Carlisle, Ph.D Advisor, H.W. Martin Post Doc Fellow ____________________________________ Andrew Slade, Ph.D Department Chair, Reader #1 ____________________________________ Bryan Bardine, Ph.D Associate Professor of English, Reader #2 ii ABSTRACT NO ME WITHOUT YOU Name: Riley, Sandra Elizabeth University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. PJ Carlisle This novel is an exploration of the narrator‟s grief as she undertakes a quest to understand the reasons for her sister‟s suicide. Through this grieving process, the heroine must confront old family traumas and negotiate ways of coping with these ugly truths. It is a novel about family secrets, trauma, addiction, mental illness, and ultimately, resilience. iii Dedicated to JLH iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my earliest reader at the University of Dayton—Dr. Meredith Doench, whose encouragement compelled me to keep writing, despite early frustrations in the drafting process. Thank you to Professor Al Carrillo—our initial conversations gave me the courage to keep writing, and convinced me that I did in fact have the makings of a novel. Thank you to Dr. Andy Slade, who has been gracious and accommodating throughout my journey to the MA, and to Dr. PJ Carlisle, who not only agreed to be my thesis advisor her last semester at UD, but gave me the direction and input I needed while understanding my vision for No Me Without You. -

DIE RPG BETA V1.3

DIE RPG BETA v1.3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1) RULE CHANGES 2) ADVANCEMENT 3) RUNNING THE ARCHETYPES (ERRATA & ADDITIONS) RUNNING THE MASTER RUNNING THE GODBINDER RUNNING THE FOOL RUNNING THE NEO NON-MASTER ANTAGONISTS NON-PLAYER ARCHETYPES 4) SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL DIE: DO YOU REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME (WE KILLED A KOBOLD AND TOOK ITS STUFF) DESIGNER NOTES 5) HANDOUTS (CHARACTER SHEETS & REFERENCE) CHARACTER SHEETS GM SHEETS, CHECKLISTS AND CHEAT SHEETS KIERON GILLEN © 2020 ART BY STEPHANIE HANS Copyright © 2020 Lemon Ink Ltd & Stéphanie Hans Studio. All rights reserved. DIE, the Die logos, and the likenesses of all characters herein or hereon are trademarks of Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (except for short excerpts for journalistic or review purposes) without the express written permission of Lemon Ink Ltd & Stéphanie Hans Studio. All names, characters, events, and places herein are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events, or places is coincidental. Representation: Law Offices of Harris M. Miller II, P.C. ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION v1.3 Hi again. As I said last time, I suspect this is the last of the Beta add-ons for DIE, at least in terms of new major content. It basically completes what I consider the core DIE Beta experience. It takes the form of the previous update, in terms of working as an errata to what already exists in the main manuals. This release also includes what was in the 1.2 release, with some more tweaks. -

HARP to Rolemaster Conversion

HARP to RMFRP Conversion Introduction This article offers some guidelines for converting characters from the High Adventure Role Playing (HARP) system to the Rolemaster Fantasy Role Playing (RMFRP) system. The systems are similar in nature, so conversions between them are reasonably simple. Types of Conversions There are several ways that characters can be converted from HARP to RMFRP. The method chosen depends on how concerned you are with having a “legal” RMFRP character and how much time you are willing to spend doing the conversion. A big influence on this choice will be the importance of the character being converted. A Player Character that is going to be around for a long time (with any luck!) should have more time and effort spent on the conversion process than a minor NPC that is only going to be encountered once. I’ve described several methods below, of course these are just guidelines and you may well choose a method that falls somewhere between any of these. Strictly Legal Method (SL): This method uses the HARP character information as a guideline for creating a new RMFRP Character from scratch. The RMFRP rules take precedence in all cases. Temporary and Potential Stats are generated, skills are purchased at each level using the available Development points, spell lists are picked and developed, etc. The character’s level may end up different than their level in HARP. Basically the character could keep adding levels until their stats and skills are close to the HARP values. This is the recommended method for Player Characters and very important NPC’s Pretty Darn Close Method (PDC). -

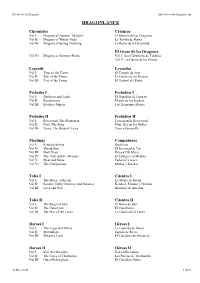

Lista De Libros En

El Orbe de los Dragones http://www.orbedragones.com DRAGONLANCE Chronicles Crónicas Vol I: Dragons of Autumn Twilight El Retorno de los Dragones Vol II: Dragons of Winter Night La Tumba de Huma Vol III: Dragons of Spring Dawning La Reina de la Oscuridad El Ocaso de los Dragones Vol IV: Dragons of Summer Flame Vol I: Los Caballeros de Takhisis Vol II: La Guerra de los Dioses Legends Leyendas Vol I: Time of the Twins El Templo de Istar Vol II: War of the Twins La Guerra de los Enanos Vol III: Test of the Twins El Umbral del Poder Preludes I Preludios I Vol I: Darkness and Light El Guardián de Lunitari Vol II: Kendermore El país de los kenders Vol III: Brothers Majere Los Hermanos Majere Preludes II Preludios II Vol I: Riverwind, The Plainsman La misión de Riverwind Vol II: Flint, The King Flint, Rey de los Gullys Vol III: Tanis, The Shadow Years Tanis el Semielfo Meetings Compañeros Vol I: Kindred Spirits Qualinost Vol II: Wanderlust El Incorregible Tas Vol III: Dark Heart Kitiara Uth Matar Vol IV: The Oath and the Measure El Código y la Medida Vol V: Steel and Stone Pedernal y acero Vol VI: The Companions Mithas y Karthay Tales I Cuentos I Vol I: The Magic of Krynn La Magia de Krynn Vol II: Kender, Gully Dwarves, and Gnomes Kenders, Enanos y Gnomos Vol III: Love and War Historias de Ansalon Tales II Cuentos II Vol I: The Reign of Istar El Reino de Istar Vol II: The Cataclysm El Cataclismo Vol III: The War of the Lance La Guerra de la Lanza Heroes I Héroes I Vol I: The Legend of Huma La Leyenda de Huma Vol II: Stormblade Espada de Reyes -

Experts Share Tips for Staying Safe

Radio: Updates on AM Friday 89 / 74 89 / 74 88 / 75 1290 and News 95.7 Today Saturday Sunday Full forecast by WHIO. Live radar at July 21, 2017 Chance of storms Chance of storms Chance of storms Eric Elwell, C4 WHIO.com COMPLETE. IN-DEPTH. DEPENDABLE. MUSIC |ARTS|M $2.00 OVIES|F OOD &DRINK |RECREATION |Friday,Jul PO y21,2017 WEREDBY BUSINESS, A11 LOCAL& STATE, B1 IN GO! NASCARLEGENDHELPSOPEN POLICEPROBEWHYSEMI HIT AC1 A$20 3-COURSE RESTAURANT SPECTRUM BRANDSFACILITY BEAVERCREEK FAMILY’SVAN WEEK MEAL?YOUBET! THETABLE ISSET JULY PAGES 8-9 23-30. LOCAL ECONOMY CRIME& COURTS Home values across Feds indict 8 in pharmacy Montgomery on rise robberies Southern suburbs, led by Kettering, account Unsealed court records for majority of gains. call Jamar Warren of Dayton the organizer. By Chris Stewart Staff Writer By Mark Gokavi Staff Writer Home and commercial prop- erty values have risen in nearly Federal prosecutors have identi- Jamar Warren (left) and David all areas of Montgomery County fied the ringleader of a suspected Harris are two of eight suspects over the past three years, the pharmacy robbery operation, in a string of pharmacy robberies. county auditor reported Thursday. according to recently unsealed A revaluation of property val- federal court records. ues in the county found higher Eight serial pharmacy robbery Warren didn’t appear Thursday home values in all but one juris- Kettering’s gain of more than $235 million was the county’s highest suspects have been re-indicted as for a scheduled preliminary hear- diction in the county. That will in a tentative update of property values. -

DIE ARCHETYPE SHEETS (Full Versions)

DIE ARCHETYPE SHEETS (Full Versions) Print if you want to use the full range of archetypes’ powers. THE NEO YOUR NAME: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ CLASS DICE: D10 STATS Adventurers’ lust for gold makes them all thieves, which Assign to your stats: 4, 4, 3, 3, 2 and 2. makes the prejudice against rogues a little odd. They all Underlined statistics are the ones most associated with do it. But everyone knows why people are suspicious this class. about Neo… STRENGTH DEXTERITY CONSTITUTION The Neo’s magical technology needs to be activated by Physicality, hand-to-hand Dodging, ranged combat, Health, amount of Fair Gold every day. It disappears every dawn. If they combat, etc. initiative, etc. damage you take, etc. can’t find enough then all their gifts means nothing. They chase it. Some practically, some obsessively, most selfishly. Adventurers all want gold but only Neo need it. WISDOM INTELLIGENCE CHARISMA Understanding, Specific knowledge, Personal skills, willpower, etc perception, etc. attractiveness, etc. DON’T READ THIS BIT ALOUD. Hey, Player. You can make choices as the player or persona or both. No matter what, please select options as the sheet describes. EQUIPMENT You start with all the following: • A Dagger (or any pointy thing which stabs) • Another Close Weapon (short sword, a second dagger or _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _) • A Ranged Weapon (shortbow, crossbow, pistol or _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _) • Leather Armour (Defence 1) YOUR LOOK Choose one of the following: • Black Leather, studs and chrome • White leather, bleach and catsuits • Billowing black cloak and sinister scarlet eyes • Exposed metallic exoskeleton and vat grown muscle • Your own idea: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ DEFENSIVE STATS CORE MECHANIC REDUX GUARD HEALTH • Roll a number of normal D6 equal to your (Guard = Dexterity) (Health = Constitution) statistic plus (if directed) your class dice. -

Cnc DLA Turambar

1 2 Dragonlance Adventures Castles & Crusades campaign sourcebook Players Handbook by Antonio Eleuteri v3.4 to my wife, Lida, and her first Dragonlance character, Nikol the aspiring knight 3 Index Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Races .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Languages ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Racial ages ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Attributes ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Human............................................................................................................................................. 6 Kender ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Elf..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Half-elf............................................................................................................................................ -

Ancient Krynn

v.1.00 Table of Contents A Travelers Guide to Ancient Istar Savage Lands: A Traveler's Guide to Nordmaar In Darkest Days: The Lost Battles and the Priests of the Moons The Holy Order of the Stars Sons of Kiri-Jolith: The Order of the Divine Hammer Campaigning through the First Cataclysm All writings and credit goes to John Grubber and all sources can be found on John Grubber’s website: http://www3.sympatico.ca/john.grubber This is an Unofficial Dragonlance Document. I am just a big fan of John’s work with some time on my hands. You can find me Canlocu at [email protected] The Glorious Empire A Travelers Guide to Ancient Istar By John Grubber Tucuri Citizens The text included here is unofficial, and is based on the Dragonlance game and fiction world, wholly owned by Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Its origins lie in an email from Chris Pierson, one of my fellow Dragonlance authors (and fellow Canadian) searching for information about Istar for a trilogy he was writing. This series of books would eventually become 'The Kingpriest Trilogy', published from 2001-2004 (Chosen of the Gods, Divine Hammer and Sacred Fire). For a fiction world nearing 20 years old, there was a great dearth of information about the greatest empire in its history. After speaking with Chris, I set about to fix this. Readers familiar with the trilogy will recognize many things in these pages- though there are many changes from the world of the novels as well. This is a natural part of the fiction writing process- some things worked, others did not. -

Friedrich Nietzsche Beyond Good and Evil a New Translation by Marion Faber

Friedrich Nietzsche Beyond Good and Evil A new translation by Marion Faber OXFORD WORLD'S CLASSICS --�- --�'-- ' OXFORD WORLD S CLASSICS BEYOND GOOD AND EVIL FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE (1844-1900) was born in Rocken, Saxony, and educated at the universities of Bonn and Leipzig. At the age of only 24 he was appointed Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Basle, but prolonged bouts of ill health forced him to resign from his post in 1879. Over the next decade he shuttled between the Swiss Alps and the Mediterranean coast, devoting himself entirely to thinking and writing. His early books and pamph lets (The Birth o.fTragedy, Untimely Meditations) were heavily influ enced by Wagner and Schopenhauer, but from Human, All Too Human (1878) on, his thought began to develop more indepen dently, and he published a series of ground-breaking philosophical works (The Gay Seima, Thus Spake Zarathustra, Beyond Go()d and Evil, On the Genealogy ofJl,forals) which culminated in a frenzy of production in the dosing months of 1888. In January 1889 Nietz sche suffered a mental breakdown from which he was never to recover, and he died in Weimar eleven years later. MARION FABER is Professor of German at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. Her earlier translations include Nietzsche's Human, All Too Human (1994) and Wolfgang Hildesheimer's Afozal't (1983), a nominee for the American Book Award in trans lation. ROBERT C. HOLUB teaches German intellectual, cultural, and literary history in the German department at the University of California, Berkeley. Among his numerous publications on these topics are Reflections of Realism (1991); Jurgen Habermas: Critic in the Public Sphere (1991); Crossing Borders: Reception Them)!, Poststruauralism, Deconstruction (1992); and Friedrich Nietzsche (1995)· He is the editor of Impure Reason: Dialectic of Enlightenment in Germany (1993), Resp()nsibiliZy and Commitment (1996), and Hein rich Heine '5 Contested Identities (1998). -

HARP Template

HARP Lite™ 1 Credits Designers: Tim Dugger & Heike A. Kubasch; name” Clark, Ben Cox, DaNita “Mahalla” Editors: Heike A. Kubasch, Tim Dugger; Crawford, Jonathan Dale, Carolyn Dennis, Patrick Additional Developers & Material: Chris Farley, Matt Fitzgerald, Hunter Fowler, Keith Adams, Gavin Bennett, Nicholas H.M. Caldwell, Grainge, Bruce Gulke, Teri Gulke, Dan Harris, Bruce Neidlinger, John Seal, Brad Williams; Richard Henderson, Michael “Daeryn” Hollis, Mark “Zelnam” Long, Jessica “Izzy” Long, David Special Contributions: Chris Adams, Gavin “Devan” Malabar, Joe Martin, Tracy McCormick, Bennett, Bjørn T. Bøe, Nicholas H.M. Caldwell, Trevor “Tor” Payne, Dave Prince, John Ross, John Brent Knorr, Bruce Neidlinger, Andrew Ridgway, “GM” Seal, Karen J. Setze, Josh Siegel, Aaron John Seal, Brad Williams, Peter Wrede, Special Smalley, David Smalley, Shaun Steere, Zack Thanks to all the fans on the ICE forums, and Troute, Stephen Watts, Scott Welker, David Sami Pyörre and his Everchanging Book of Weyth, Melissa Weyth, Jody Willson, Jesse Wood, Names (EBoN), a shareware random name Russell Wood, Phil “Yukohno” Wright; generator used to generate many of the names in ICE Staff— this product. It can be downloaded from http:// ebon.pyorre.net; President: Heike A. Kubasch; CEO: Bruce Neidlinger; Cover Art: Ciruelo: “Fafner”; Managing Editor: Heike A. Kubasch; Interior Art: Toren “MacBin” Atkinson, Peter Editing, Development, & Production Staff: Heike Bergting, David Bezzina, Matt Foster, Eric Hotz, A. Kubasch, Bruce Neidlinger, Tim Dugger, Mike Jackson, Jeff Laubenstein, Pat Ann Lewis, Lori Dugger; Larry MacDougall, Jennifer Meyer, Colin Web Mistress: Monica L. Wilson; Throm, Kieran Yanner; Corporate Mascots: Gandalf T. Cat, Rajah T. Art Direction: Jeff Laubenstein; Cat, Phoebe T. -

Legendofmana.Pdf

Introduction egend of Mana is a game of epic magnitude. It isn't a straightforward RPG like most others on the market today. Instead, you pick your own quests, and how to build your character. You choose how to build the land and who to help over the course of your adventures. You'll meet many memorable characters over your travels, some of which will join you, while the others will oppose you. The Legend of Mana takes place in the same world as the Secret of Mana for the Super Nintendo. But it is many years later and the Mana Tree is dying. The world is in ruins and you have to use the power of your mind to reconstruct it with the help of powerful artifacts. It is up to you to bring peace back to the land and rebuild it. Foremost, you are to witness what is happening in the land, as people return to the lives they had before the land was torn apart. This game contains beautifully hand-drawn backgrounds and characters. The music is great as well. But what draws me to the game is the long list of quests that are to be done, as well as the more than 200 special moves! The extra features available at your Home are also a plus.This is a great game that will have you coming back for more and more! The game can also be played with a second player, but it is not like in the Secret of Mana. It is no longer coop, but more of a follower situation. -

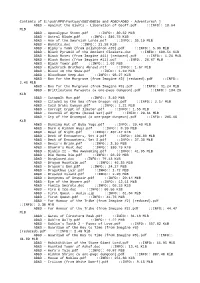

Contents of E:\Pub\RPG\Fantasy\D&D\D&D1e

Contents of E:\pub\RPG\Fantasy\D&D\D&D1e and AD&D\AD&D - Adventures\ ] AD&D - Against the Giants - Liberation of Geoff.pdf ::INFO:: 18.64 MiB AD&D - Apocalypse Stone.pdf ::INFO:: 30.62 MiB AD&D - Astral Blade.pdf ::INFO:: 346.78 KiB AD&D - Axe of the Dwarvish Lords.pdf ::INFO:: 35.19 MiB AD&D - Bandits.doc ::INFO:: 21.58 KiB AD&D - Bigby's Tomb (from polyhedron #20).pdf ::INFO:: 5.36 MiB AD&D - Black Pyramid of the Ancient Cloakers.doc ::INFO:: 180.51 KiB AD&D - Black Roses (from Imagine #11) (reduced).pdf ::INFO:: 1.21 MiB AD&D - Black Roses (from Imagine #11).pdf ::INFO:: 20.67 MiB AD&D - Black Tower.pdf ::INFO:: 1.63 MiB AD&D - Blackrock Brothers Abroad.rtf ::INFO:: 1.67 MiB AD&D - Blood on the Snow.pdf ::INFO:: 1.10 MiB AD&D - Bloodbane Keep.doc ::INFO:: 98.27 KiB AD&D - Box for the Margrave (from Imagine #3) (reduced).pdf ::INFO:: 2.48 MiB AD&D - Box for the Margrave (from Imagine #3).pdf ::INFO:: 31.24 MiB AD&D - Brittlestone Parapets (a one-page dungeon).pdf ::INFO:: 134.29 KiB AD&D - Catapult Run.pdf ::INFO:: 3.10 MiB AD&D - Citadel by the Sea (from Dragon 78).pdf ::INFO:: 2.17 MiB AD&D - Cold Drake Canyon.pdf ::INFO:: 1.21 MiB AD&D - Corrupt Crypt of Ilmater.pdf ::INFO:: 1.55 MiB AD&D - Council of Wyrms (boxed set).pdf ::INFO:: 29.61 MiB AD&D - Cry of the Gravegod (a one-page dungeon).pdf ::INFO:: 285.16 KiB AD&D - Dancing Hut of Baba Yaga.pdf ::INFO:: 29.48 MiB AD&D - Dark & Hidden Ways.pdf ::INFO:: 8.20 MiB AD&D - Dead of Night.pdf ::INFO:: 402.42 KiB AD&D - Deck of Encounters, Set 1.pdf ::INFO:: 104.80 MiB AD&D - Deck of Encounters,