The Ngāpuhi Mandate Inquiry Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Draft.21

9th Annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Virtual Symposium “Food is Resistance” Saturday, June 5th 2021 Hosted by University of Washington’s American Indian Studies Department and the Na’ah Illahee Fund Find us at: https://livingbreathfoodsymposium.org/ www.facebook.com/UWLivingBreath Twitter - @LivingBreathUW Welcome from our Symposium Committee! First, we want to acknowledge and pay respect to the Coast Salish peoples whose traditional territory our event is normally held on at the University of Washington’s wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ Intellectual House. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to come together last year but we are so grateful to be able to reunite this year in a safe virtual format. We appreciate the patience of this community and our presenters’ collective understanding and we are thrilled to be back. We hope to be able to gather in person in 2022. We are also very pleased you can join us today for our 9th annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Symposium. This event brings together individuals to share their knowledge and expertise on topics such as Indigenous foodways and ecological knowledge, Tribal food sovereignty and security initiatives, traditional foods/medicines and health/wellness, environmental justice, treaty rights, and climate change. Our planning committee is composed of Indigenous women who represent interdisciplinary academic fields of study and philanthropy and we volunteer our time to host this annual symposium. We are committed to Indigenous food, environmental, and social justice and recognize the need to maintain a community-based event as we all carry on this important work. We host this event and will continue to utilize future symposia to better serve our Indigenous communities as we continue to foster dialogue and build collaborative networks to sustain our cultural food practices and preserve our healthy relationships with the land, water, and all living things. -

Te Runanga 0 Ngai Tahu Traditional Role of the Rona!Sa

:I: Mouru Pasco Maaka, who told him he was the last Maaka. In reply ::I: William told Aritaku that he had an unmerried sister Ani, m (nee Haberfield, also Metzger) in Murihiku. Ani and Aritaku met and went on to marry. m They established themselves in the area of Waimarama -0 and went on to have many children. -a o Mouru attended Greenhills Primary School and o ::D then moved on to Southland Girls' High School. She ::D showed academic ability and wanted to be a journalist, o but eventually ended up developing photographs. The o -a advantage of that was that today we have heaps of -a beautiful photos of our tlpuna which we regard as o priceless taolsa. o ::D Mouru went on to marry Nicholas James Metzger ::D in 1932. Nick's grandfather was German but was o educated in England before coming to New Zealand. o » Their first son, Nicholas Graham "Tiny" was born the year » they were married. Another child did not follow until 1943. -I , around home and relished the responsibility. She Mouru had had her hopes pinned on a dainty little girl 2S attended Raetihi School and later was a boarder at but instead she gave birth to a 13lb 40z boy called Gary " James. Turakina Maori Girls' College in Marton. She learnt the teachings of both the Ratana and Methodist churches. Mouru went to her family's tlU island Pikomamaku In 1944 Ruruhira took up a position at Te Rahui nui almost every season of her life. She excelled at Wahine Methodist Hostel for Maori girls in Hamilton cooking - the priest at her funeral remarked that "she founded by Princess Te Puea Herangi. -

Treaty Rights in the Waitangi Tribunal

© New Zealand Centre for Public Law and contributors Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand December 2010 The mode of citation of this journal is: (2010) 8 NZJPIL (page) The previous issue of this journal is volume 8 number 1, June 2010 ISSN 1176-3930 Printed by Geon, Brebner Print, Palmerston North Cover photo: Robert Cross, VUW ITS Image Services CONTENTS Judicial Review of the Executive – Principled Exasperation David Mullan .......................................................................................................................... 145 Uncharted Waters: Has the Cook Islands Become Eligible for Membership in the United Nations? Stephen Smith .......................................................................................................................... 169 Legal Recognition of Rights Derived from the Treaty of Waitangi Edward Willis.......................................................................................................................... 217 The Citizen and Administrative Justice: Reforming Complaint Management in New Zealand Mihiata Pirini.......................................................................................................................... 239 Locke's Democracy v Hobbes' Leviathan: Reflecting on New Zealand Constitutional Debate from an American Perspective Kerry Hunter ........................................................................................................................... 267 The Demise of Ultra Vires in New Zealand: -

Submission on Water Issues in Aotearoa New Zealand

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights United Nations Office CH 1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland Submission on Water Issues in Aotearoa New Zealand By Dr Maria Bargh 1 This submission is provided in two Parts: Part One: Overview of the significance of water to Māori and current national legislation relating to water. Part Two: Overview of the potential impacts of the New Zealand government’s proposals on Māori, including with regard to private sector provisions of related services. Introduction In 2003 the New Zealand government established a Sustainable Water Programme of Action to consider how to maintain the quality of New Zealand’s water and its sustainable use. One of the models being proposed for the more efficient management of water is the market mechanism. Dominant theories internationally put forward the market as the best mechanism by which to manage resources efficiently. Given that all life on the planet needs water for survival its appropriate management, use and sustainability is of vital concern. However many communities, including Indigenous peoples, have widely critiqued the market, and the neoliberal policies which promote it, highlighting the responsiveness of the market to money rather than need. In the case of Aotearoa, moves to further utilise the market mechanism in the governance of water raises questions, not simply around the efficiency of the market in this role but also around the Crown i approach which is one of dividing the issues of marketisation, ownership and sustainability in the same manner in which they assume the river/lake beds, banks and water can be divided. -

And Did She Cry in Māori?”

“ ... AND DID SHE CRY IN MĀORI?” RECOVERING, REASSEMBLING AND RESTORYING TAINUI ANCESTRESSES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Diane Gordon-Burns Tainui Waka—Waikato Iwi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Canterbury 2014 Preface Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha Waikato River, the ancestral river of Waikato iwi, imbued with its own mauri and life force through its sheer length and breadth, signifies the strength and power of Tainui people. The above proverb establishes the rights and authority of Tainui iwi to its history and future. Translated as “Waikato of a hundred chiefs, at every bend a chief, at every bend a chief”, it tells of the magnitude of the significant peoples on every bend of its great banks.1 Many of those peoples include Tainui women whose stories of leadership, strength, status and connection with the Waikato River have been diminished or written out of the histories that we currently hold of Tainui. Instead, Tainui men have often been valorised and their roles inflated at the expense of Tainui women, who have been politically, socially, sexually, and economically downplayed. In this study therefore I honour the traditional oral knowledges of a small selection of our tīpuna whaea. I make connections with Tainui born women and those women who married into Tainui. The recognition of traditional oral knowledges is important because without those histories, remembrances and reconnections of our pasts, the strengths and identities which are Tainui women will be lost. Stereotypical male narrative has enforced a female passivity where women’s strengths and importance have become lesser known. -

Document 2 Contributors

DOCUMENT 2 CONTRIBUTORS Architects and Builders: Health: Barnaby Bennett, Architect Northland DHB Harnett Building Tiaho Trust NZ Institute of Building Maoridom: Arts: Elizabeth Ellis and Patu Hohepa Hamish Keith Hihiaua Cultural Centre Trust, Richard Drake Barnaby Weir, Musician Maori Advisory Panel, Elizabeth Ellis Jenny Bennett Group, Artists Te Huinga, Pita Tipene Paul McLaney, Mushroom Music Steve Moase, Artist and Musician Sport: Dianne Swann - Musician Activ8 Business: Northland Football League Sport Northland Advantage Business Northland Andrew Garratt, Human Resources Manager Stats and Surveys: Northland Chamber of Commerce Golden Kiwi Holdings Holiday Park Stats Northland Economic Action Group Legacy of Hundertwasser in Kawakawa Sir Michael Hill Survey report for Cruise NZ Webb Ross Lawyers Te Taitokerau Teachers Survey Whangarei Economic Development Group Latest Media Release Cruise NZ_ 30-09-2014 Whangarei CBD Hospitality Group Photgraphic Parking Survey_C King World of Decor Burning Issues Gallery - Jan Twentyman Tourism: Northland Branch Hospitality NZ Jane Scripps, B&B manager Marsden Woods Inskip Smith - Lawyers Positively Wellington Shorestone - Consultants Sir Bob Harvey Hospitality Northland Top Ten Holiday Park, Kevin and Linda Lloyd Tourism Bay of Plenty Education: Tourism N.Z. Adrian Smith, Principals Association Whangarei Visitors Group Julia Parry, Teacher Tourism Industry Association People Potential Pompellier College students Under 40’s: Whangarei Boys High School Board of Trustees Ben Tomason Group Taleesha -

Chairman's Report

CHAIRMAN'S 05 REPORT 10 F E E S & Building the 06 07 ATTENDANCE INTRODUCTION TRUSTEES Hauraki nation, 10 STRATEGY IWI REGISTER 12 & PLANNING together! 13 14 24 ASSETS INTERACTIONS FINANCIALS - IWI, MARAE,MATAURANGA EDUCATION & SPORTS 48 16 GRANTS SCORECARD Ngā Puke ki Hauraki ka tarehu Nga mihinui Kia koutou i tenei wa As other opportunities come our way in E mihi ana ki te whenua aquaculture and fin fish farming we look forward On behalf of the Trustees of the Pare Hauraki to working alongside the company to realise the E tangi ana ki te tangata Fishing Trust I am pleased to present this Annual potential of those opportunities and to enable Report for 1st October 2017 to 30th September further economic growth and opportunities for E ngā mana, e ngā Iwi, 2018. business and employment for our people in the future. E ngā uri o ngā Iwi o Hauraki The Trust’s fundamental function is to provide the Iwi, Marae Development, Education, Mātauranga Because of the strength of our collective fisheries Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, (Culture & Arts) and Sports grants on an annual assets we are having a strong influence in basis. This has been a very good way to assist our aquaculture and fisheries development across our Tēnā tātou katoa. people of Ngā Iwi o Hauraki and our many Marae. rohe and the country. Our Annual Report identifies where those grants As we need necessary infrastructure to support were allocated and their purpose and it will be our growth we are also engaging strongly great to hear from some of those recipients at our with Local and Central Government to work Annual General Meeting as we have heard from collaboratively to secure resource, particularly other recipients in previous years. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

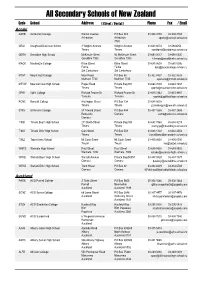

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Whale Rider: the Re-Enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Kevin V

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 16 Article 9 Issue 2 October 2012 10-1-2012 Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Kevin V. Dodd Watkins College of Art, Design, and Film, [email protected] Recommended Citation Dodd, Kevin V. (2012) "Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 16 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol16/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Whale Rider: The Re-enactment of Myth and the Empowerment of Women Abstract Whale Rider represents a particular type of mythic film that includes within it references to an ancient sacred story and is itself a contemporary recapitulation of it. The movie also belongs to a further subcategory of mythic cinema, using the double citation of the myth—in its original form and its re-enactment—to critique the subordinate position of women to men in the narrated world. To do this, the myth is extended beyond its traditional scope and context. After looking at how the movie embeds the story and recapitulates it, this paper examines the film’s reception. To consider the variety of positions taken by critics, it then analyses the traditional myth as well as how the book first worked with it. The onclusionc is, in distinction to the book, that the film drives a wedge between the myth’s original sacred function to provide meaning in the world for the Maori people and its extended intention to empower women, favoring the latter at the former’s expense. -

Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Annual Report 2020 Nga Rarangi Take

Nga Rarangi Take Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Annual Report 2020 Nga Rarangi Take Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi When the old net is cast aside, the new net goes fishing, our new strategy remains founded on our vision. Nga Rarangi Take CONTENTS Nga Rarangi Take Introduction/Snapshot 4 Te Arawa 500 scholarships 26 Highlights - 2020 5 Iwi Partnership Grants Programme 27 Your Te Arawa Fisheries 6 Te Arawa Mahi 28 Our Mission/Vision 8 INDIGI-X 29 Message form the Chair 9 Looking to the Future 30 CEO’s Report 10 Research and Development 31 COVID-19 11 Smart Māori Aquaculture Ngā Iwi i Te Rohe o Te Waiariki 32 Rotorua Business Awards Finalist 12 Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao te Rangatahi Taking our Strategy to the next level 14 Te Arawa Fisheries Climate Change Strategy 34 Governance Development 16 Aka Rākau Strategic Partnerships and Investing for the Future 18 Te Arawa Carbon Forestry Offset Programme 36 Te Arawa Fresh - What Lies Beneath 20 Te Arawa Fresh Online 21 APPENDIX 1: T500 Recipients 38 Our People 22 APPENDIX 2: 2019-2020 Pataka Kai Recipients 40 Our Team 22 APPENDIX 3: AGM Minutes of the Meeting for Te Arawa Fisheries 42 Diversity Report 24 Financial Report 2020 45 Our board of trustees: from left to right. Tangihaere MacFarlane (Ngati Rangiwewehi), Christopher Clarke (Ngati Rangitihi), Blanche Reweti (Ngati Tahu/Whaoa), Dr Kenneth Kennedy (Ngati Rangiteaorere), back Willie Emery (Ngati Pikiao), in front of Dr Ken Roku Mihinui (Tuhourangi), Paeraro Awhimate (Ngati makino), in front Pauline Tangohau (Te Ure o Uenukukopako), behind Punohu McCausland (Waitaha), Tere Malcolm (Tarawhai) Nga Rarangi Take Introduction/Snapshot Timatanga Korero e Kotahitanga o Te Arawa Waka Fisheries Trust Board was legally established on T19 December 1995 by a deed of trust. -

Report to Te Rūnanga O Ngāi Tahu: Māori Educational Achievement in the Christchurch Health and Development Study

Report to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu: Māori Educational Achievement in the Christchurch Health and Development Study David M. Fergusson, Geraldine F.H. McLeod, Te Maire Tau, Angus H. Macfarlane Copyright © 2014 David M. Fergusson, Geraldine F.H. McLeod, Te Maire Tau, Angus H. Macfarlane The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-473-27220-3 A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand (Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa). This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The opinions expressed and conclusions drawn in this Working Paper are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, University of Canterbury. For further information or additional copies of the Working Paper, please contact the publisher. Ngāi Tahu Research Centre University of Canterbury Private Bag 4800 Christchurch 8140 New Zealand Email: [email protected] www.ntrc.canterbury.ac.nz Cover: Background image – from Tom Green’s notebook (c. 1860s, Christchurch, University of Canterbury, Macmillan Brown Library, Ngāi Tahu Archives, M 22.) Report to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu: Māori Educational Achievement in the Christchurch Health and Development Study AUTHORS David M. Fergusson Christchurch Health and Development Study at the University of Otago, Christchurch Geraldine F.H. McLeod Christchurch Health and Development Study at the University of Otago, Christchurch Te Maire Tau Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, University of Canterbury, Christchurch Angus H. -

AFF / NFF Idme Ground Codes Northland

AFF / NFF iDMe Ground Codes Northland DGCUL McKay Stadium Office (NFF) IGUFE Ruakaka UGQSQ Awanui Sports Complex MVPEW Ruawai College WDHHV Bay of Islands College PXUGO Russell Primary School FKJNO Bay of Islands International Academy FYVDL Russell Sports Ground KIPEO Baysport Waipapa EFIXD Semenoff Stadium HHHKU Bledisloe Domain GGPPR Taipa School ERHSY Bream Bay College ECNNG Tarewa Park JWFFS Dargaville High School JYRVA Tauraroa Area School TUILP Huanui College OKGJA Tikipunga High School PNJUW Hurupaki School XLYCV Tikipunga Park MYCUE Kaitaia College FQFLT Wentworth College EDDPP Kamo High School GFREY Whangarei Boys High School KAQYF Kamo Sports Park HCWJP Whangarei Events Centre VJXGP Kensington Park OXMXD Whangarei Girls High School PMYOV Kerikeri Domain AJBAU Whangarei Heads School HJLJR Kerikeri High School LONEC Whangaroa College TPSGS Kerikeri Primary School ORKEG William Fraser Park OQVUW Koropupu Sports Park YDFDF Lindvart Park SLRHR Mangakahia Sports Complex 1 CMLAN Mangawhai Beach School THSQQ Mangawhai Domain YTMYF Maunu School DCSID Memorial Park (Dargaville) HWBQQ Moerewa School GHNSJ Morningside Park KBAHC Ngunguru Sports Complex JQPCR Northland College IFAWA Ohaeawai Primary School FQRIG Okaihau College RMTIB Okaihau Primary School YNQBF Omapare School VMEXN Onerahi Airport IQRIR Opononi Area School YBNXY Oromahoe Primary School FYMAM Otaika Domain AYIUU Otamatea High School MUQPV Parua Bay School SIERO Pompallier College JYTGB Puriri Park Reserve ELXMD Riverview Primary School North Harbour / Waitakere GNOFF North