Contextualizing Indigenous Church Principles: an African Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICA's ANNEXATION of HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE

A LUSCIOUS FRUIT: AMERICA’S ANNEXATION OF HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR JOSEPH A. FRY KARI FREDERICKSON LISA LIDQUIST-DORR STEVEN BUNKER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Becky L. Bruce 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the annexation of Hawaii was not the result of an aggressive move by the United States to gain coaling stations or foreign markets, nor was it a means of preempting other foreign nations from acquiring the island or mending a psychic wound in the United States. Rather, the acquisition was the result of a seventy-year relationship brokered by Americans living on the islands and entered into by two nations attempting to find their place in the international system. Foreign policy decisions by both nations led to an increasingly dependent relationship linking Hawaii’s stability to the U.S. economy and the United States’ world power status to its access to Hawaiian ports. Analysis of this seventy-year relationship changed over time as the two nations evolved within the world system. In an attempt to maintain independence, the Hawaiian monarchy had introduced a westernized political and economic system to the islands to gain international recognition as a nation-state. This new system created a highly partisan atmosphere between natives and foreign residents who overthrew the monarchy to preserve their personal status against a rising native political challenge. These men then applied for annexation to the United States, forcing Washington to confront the final obstacle in its rise to first-tier status: its own reluctance to assume the burdens and responsibilities of an imperial policy abroad. -

New England Congregationalists and Foreign Missions, 1800-1830

University of Kentucky UKnowledge History of Religion History 1976 Rebuilding the Christian Commonwealth: New England Congregationalists and Foreign Missions, 1800-1830 John A. Andrew III Franklin and Marshall College Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Andrew, John A. III, "Rebuilding the Christian Commonwealth: New England Congregationalists and Foreign Missions, 1800-1830" (1976). History of Religion. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_history_of_religion/3 REBUILDING THE CHRISTIAN COMMONWEALTH New England Congregationalists & Foreign Missions, 1800-1830 Rebuilding the Christian Commonwealth John A. Andrew III The University Press of Kentucky ISBN: 0-8131-1333-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-38214 Copyright © 1976 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Search for Identity 4 2. A Panorama of Change 25 3. The New England Clergy and the Problem of Permanency 36 4. The Glory Is Departed 54 5. Enlisting the Public 70 6. -

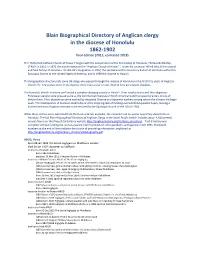

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the Diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican clergy in the Diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902 The ‘Reformed Catholic Church of Hawai’i’ began with the consecration of the first bishop of Honolulu, Thomas Nettleship STALEY in 1861. In 1872 the diocese became the Anglican church of Hawai’i, under his successor Alfred WILLIS the second bishop of Honolulu. On WILLIS’s resignation in 1902, the see became a missionary district within the Episcopal Church of the United States of America, and in 1969 the diocese of Hawai'i. This biographical directory lists over 50 clergy who passed through Honolulu in the first forty years of Anglican church life. Few priests were in the diocese of Honolulu more than a year or two. Many biographies reveal visionary hopes and bitter disappointments. Several lives are shadowy to the point of invisibility. At the end of the sections in the biographies, bracketed numbers indicate the sources of preceding information. The Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the South Pacific (which includes some 1,650 priests) may be found on the Kinder library website, in Auckland New Zealand. These bracketed numbers are there given bibliographical substance in a document accompanying the biographical directory. The compiler points out that this directory has been researched and compiled without funding. I am very grateful to the hundreds of correspondents and agencies who have voluntarily assisted me on this work since the early 1990s. The compiler welcomes corrections and additions sent to [email protected]. Such will be incorporated in the master-copy held in Wellington New Zealand, and in due course in the online version of this directory with Project Canterbury. -

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Abcfm)

AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS (ABCFM) AND “NOMINAL CHRISTIANS”: ELIAS RIGGS (1810-1901) AND AMERICAN MISSIONARY ACTIVITIES IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE by Mehmet Ali Dogan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Studies/History Department of Languages and Literature The University of Utah May 2013 Copyright © Mehmet Ali Dogan 2013 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Mehmet Ali Dogan has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Peter Sluglett Chair 4/9/2010 Date Approved Peter von Sivers Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved Roberta Micallef Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved M. Hakan Yavuz Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved Heather Sharkey Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved and by Johanna Watzinger-Tharp Chair of the Department of Middle East Center and by Donna M. White, Interim Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I investigate the missionary activities of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Ottoman Empire. I am particularly interested in exploring the impact of the activities of one of the most important missionaries, Elias Riggs, on the minorities in the Ottoman Empire throughout the nineteenth century. By analyzing the significance of his missionary work and the fruits of his intellectual and linguistic ability, we can better understand the efforts of the ABCFM missionaries to seek converts to the Protestant faith in the Ottoman Empire. I focus mainly on the period that began with Riggs’ sailing from Boston to Athens in 1832 as a missionary of the ABCFM until his death in Istanbul on January 17, 1901. -

Full Issue: Volume 5, Number 1 (2020)

Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology Volume 5 Number 1 Article 1 2020 Full Issue: Volume 5, Number 1 (2020) Spiritus Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/spiritus Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Spiritus Editors (2020) "Full Issue: Volume 5, Number 1 (2020)," Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/spiritus/vol5/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Theology & Ministry at Digital Showcase. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology by an authorized editor of Digital Showcase. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume'5' ' Number'1''Spring'2020 Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology Volume 5, Number 1 (Spring 2020) ISSN: 2573-6345 Copyright © 2020 Oral Roberts University; published by ORU’s College of Theology and Ministry and the Holy Spirit Research Center. All rights reserved. To reproduce by any means any portion of this journal, one must first receive the formal consent of the publisher. To request such consent, write Spiritus Permissions – ORU COTM, 7777 S. Lewis Ave., Tulsa, OK 74171 USA. Spiritus hereby authorizes reproduction (of content not expressly declared not reproducible) for these non- commercial uses: personal, educational, and research, but prohibits re-publication without its formal consent. -

Hawaii: the Past, Present, and Future of Its Island-Kingdom"

Full text of "Hawaii: the past, present, and future of its island-kingdom" � � � � � � � � � �Sign In Full text of "Hawaii: the past, present, and future of its island-kingdom" See other formats This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was c arefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A pub lic domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may var y country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often dif ficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a remi nder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely acc essible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep p roviding this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we r equest that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. -

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the Diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902 Final Edition (2012, Corrected 2018)

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican clergy in the diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902 final edition (2012, corrected 2018) The “Reformed Catholic Church of Hawai’i” began with the consecration of the first bishop of Honolulu, Thomas Nettleship STALEY in 1861. In 1872 the diocese became the “Anglican Church of Hawai’i”, under his successor Alfred WILLIS the second and final bishop of Honolulu. On WILLIS’s resignation in 1902, the see became the missionary district of Honolulu within the Episcopal Church of the United States of America, and in 1969 the diocese of Hawai'i. This biographical directory lists some 58 clergy who passed through the diocese of Honolulu in the first forty years of Anglican church life. Few priests were in the diocese more than a year or two. Several lives are evasive shadows. The Honolulu church initiative confronted a complex changing society in Hawai’i. Their royal patrons and the indigenous Polynesian people were pressed aside as the commercial interests of North American (and European) planters drove all before them. Their plantations were worked by imported Chinese and Japanese workers among whom the diocese did begin work. The inadequacies of diocesan leadership and the crippling lack of funding overwhelmed quixotic hopes, leaving a divided and worn Anglican remnant to be rescued by the Episcopal church of the USA in 1902. While these entries were compiled from the best evidence available, the compiler had no access to primary documents in Honolulu. The full Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the South Pacific (which includes about 1,500 priests) may be found on the Project Canterbury website http://anglicanhistory.org/nz/blain_directory/ That directory was compiled without funding but with assistance from hundreds of correspondents and agencies from 1991. -

Forty-Ninth Report American Board Of

FORTY-NINTH REPORT OP THE AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS, PRESENTED A.T THE MEETING- HELD AT DETROIT, MICHIGAN, SEPTEM BER 7 — 10, 1858 . BOSTON: PRESS OF T. R. MARVIN & SON, 42 CONGRESS STREET. 1858. /S 'E 6 ZS’ A v.49- S'S MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL MEETING. T he A m erican B oard of C ommissioners fo r F oreign M issions held its Forty-ninth Meeting in the First Presbyterian Church, Detroit, Michigan, commencing Tuesday, September 7, 1858, at 4 o’clock, P. M., and closing Friday, September 10, at 10 o’clock, A . M. CORPORATE MEMBERS PRESENT. Maine. Rhode Island. John W . Chickering, D . D'. Thomas Shepard, D . D. George E . Adams, D.D. John Kingsbury, LL. D. New Hampshire. Zedekiah S. Bar stow, D . D. Connecticut. Alvan Bond, D . D. Vermont. Leonard Bacon, D . D. Rev. David Greene. Silas Aiken, D.D. New York. "Willard Child, D . D. Nathan S. S. Beman, D. D. Massachusetts. Reuben H . Walworth, LL. D. Mark Hopkins, D . D. Calvin T. Hulburd, Esq. Henry Hill, Esq. Simeon Benjamin, Esq. Rufus Anderson, D.D. Rev. George W . Wood. Rev. Aaron AVamer. Rev. William S. Curtis. Ebenezer Alden, M. D . Jacob M. Schermerhpm, Esq. Swan Lyman Pomroy, D.D. Rev. Selah B. Treat. New Jersey. Hon. Linns Child. J. Marshal Paul, M. D . Henry B. Hooker, D . D . Rev. Thornton A . Mills. Samuel M. Worcester, D.D. Lyndon A . Smith, M. D. iAndrew W . Porter, Esq. Hon. William T. Eustis. Pennsylvania. ft Hon. John Aiken. * 1James M. Gordon, Esq. -

I FOSTERING SUSTAINABILITY & MINIMIZING DEPENDENCY IN

FOSTERING SUSTAINABILITY & MINIMIZING DEPENDENCY IN MISSION FINANCES by Ken Stout An Integrative Thesis Submitted to the faculty Of Reformed Theological Seminary in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Religion) Approved: Thesis Advisor: ________________________________ The Rev. Samuel H. Larsen, Ph.D. RTS/Virtual President: ___________________________ Andrew J. Peterson, Ph.D. October 2008 i ABSTRACT Fostering Sustainability & Minimizing Dependency in Mission Finances Ken Stout There has arisen over the past several decades in the Western church a renewed interest in the debate concerning the use of finances in missions. Missionary efforts from developed nations must embrace practices which minimize dependency on foreign funding and emphasize local sustainability in order to achieve long-term spiritual vitality among developing-world congregations. In the colonial era, most mission organizations retained nearly total control over their ministries in the receiving nations and financed their mission efforts via donations from sending nations. In the post-colonial era, many denominations and agencies began to consider how to increase indigenous leadership and drafted plans whereby funding would transfer from sending to receiving nations. Since 1990, the concept of partnership in ministry between developed and developing-world churches has grown in popularity. Dependency occurs when a local church requires funding or leadership from outside of its own members in order carry out the core biblical responsibilities of a local church under normal conditions. Consequences of financial dependency include a lack of ownership, stunted growth, mixed motives in leadership, confused accountability, suspicion of foreign influence, and compromised witness. For a church to be sustainable it must be able to carry out its core biblical functions without relying on foreign funding or leadership. -

Claiming Christianity: the Struggle Over God and Nation in Hawaiʻi, 1880–1900

CLAIMING CHRISTIANITY: THE STRUGGLE OVER GOD AND NATION IN HAWAIʻI, 1880–1900 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DECEMBER 2013 By Ronald C. Williams Jr. Dissertation Committee: Jonathan K. Osorio, Chairperson David Hanlon David Chappell Suzanna Reiss Noenoe Silva Copyright © 2013 Ronald Clayton Williams Jr. All rights reserved i This work is dedicated to the many remarkably generous, kind, and gracious folks who, without pause, opened their churches, their homes, and their lives to me over the past ten years as we listened to voices and shared stories. This story is yours, and that of your kūpuna, and I am humbled to have been given the opportunity to discover it along with you. Also, to the numerous writers of the past, who, with foresight and dedication, documented their unending devotion to their ‘āina and their lāhui. I am sincerely blessed to have been a part of all that has happened during this work. Mahalo nō hoʻi. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Anyone who has taken on a project such as this knows well the great debt that is owed to the numerous people that have contributed to its completion in a variety of ways. It exists because of each of them, and in this work, I am deeply grateful to all. I start with thanks to my first kumu, the late Akoni Akana, who took a skinny, haole, farm-boy from Arkansas under his wing and generously shared much more than I deserved. -

FULL ISSUE (44 Pp., 2.2 MB PDF)

A quarterly publication of the Overseas Ministries Study Center Vol. 3. No.3 continuing the Occasional Bulletin from the Missionary Research Library July, 1979 ccaslona • etln• Communication-In Word and Deed ommunicating the gospel, the primary task of Christian Thanks, and a Request C mission, is an ongoing process. It is not merely verbal, and it is never a monologue. The enormous complexity of the task is The circulation of the Occasional Bulletin has grown dramatically to reflected in the articles comprising this issue of the Occasional more than 7000 in just two years. We are gratified by this response Bulletin. and by the numerous letters of appreciation and inquiry (even Tracey K. Jones, [r., examines the possibilities for communica telephone calls from as far away as Alaska and Hawaii). It would tion between worldwide Christianity and the People's Republic of help us further if subscribers would notify our circulation depart China, the largest nation on earth. "Over the past 1600 years," he ment immediately of any change-of-address, and please send in writes, lithe Christian faith has entered China four times. Three your subscription renewal promptly. times it has been swallowed up and disappeared." Our fourth and most recent experience also indicates the precariousness of the Christian dialogue with the Chinese people. Foreseeing missionary directions in the 1980s, Johannes Verkuyl addresses the difficulties of communicating the gospel in a religiously plural world. He contends for fresh ways to express the gospel's universality in a real encounter with people of other 90 Christian Mission among the Chinese People: faiths, eliminating the dichotomy between verbal proclamation on Where Do We Go from Here? the one hand, and koinonia, diakonia, and the struggle for justice on Tracey K. -

Christian Missions, Anti-Slavery and the Claims of Humanity, C

1 Christian Missions, Anti-Slavery and the Ambiguities of ‘Civilisation’, c. 1813-18731 Brian Stanley University of Cambridge 1. Introduction During this period Protestant forms of Christianity were implanted in southern and western Africa and Australasia, greatly extended their existing limited influence in south Asia, the Caribbean, and the Dutch East Indies, and gained precarious footholds in east Africa and the vast Chinese empire. In terms of geographical coverage, though not of numbers of converts, this was an age of rapid Protestant missionary expansion. At the beginning of this period, the Catholic presence in the non-western world was weak in comparison. Despite Napoleon’s reconstitution of the French religious orders in 1805 and Pius VII’s re-establishment of the Jesuit order in 1814, Catholic missions had not yet recovered from the catastrophes of the revolutionary era. It is estimated that in 1815 there were no more than twenty missionary priests in India, and 270 throughout the globe.2 By 1873, Catholic missions were again a force to be reckoned with, and increasingly feared by their Protestant rivals. Old orders had been reconstituted, and new ones founded, among them the Marists (1817), the Missionaries of the Most Holy Heart of Mary (1841), and the Society of Missionaries of Africa or White Fathers (1868). Other missionary orders, such as the Paulist 1 Some of this paper was subsequently published in my article ‘Christian missions, antislavery, and the claims of humanity, c. 1813-1873’ in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley (eds.), World Christianities, c. 1815-c. 1914: The Cambridge History of Christianity volume 8 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp.