Public Key Encryption with Keyword Search (PEKS) Scheme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public-Key Cryptography

Public Key Cryptography EJ Jung Basic Public Key Cryptography public key public key ? private key Alice Bob Given: Everybody knows Bob’s public key - How is this achieved in practice? Only Bob knows the corresponding private key Goals: 1. Alice wants to send a secret message to Bob 2. Bob wants to authenticate himself Requirements for Public-Key Crypto ! Key generation: computationally easy to generate a pair (public key PK, private key SK) • Computationally infeasible to determine private key PK given only public key PK ! Encryption: given plaintext M and public key PK, easy to compute ciphertext C=EPK(M) ! Decryption: given ciphertext C=EPK(M) and private key SK, easy to compute plaintext M • Infeasible to compute M from C without SK • Decrypt(SK,Encrypt(PK,M))=M Requirements for Public-Key Cryptography 1. Computationally easy for a party B to generate a pair (public key KUb, private key KRb) 2. Easy for sender to generate ciphertext: C = EKUb (M ) 3. Easy for the receiver to decrypt ciphertect using private key: M = DKRb (C) = DKRb[EKUb (M )] Henric Johnson 4 Requirements for Public-Key Cryptography 4. Computationally infeasible to determine private key (KRb) knowing public key (KUb) 5. Computationally infeasible to recover message M, knowing KUb and ciphertext C 6. Either of the two keys can be used for encryption, with the other used for decryption: M = DKRb[EKUb (M )] = DKUb[EKRb (M )] Henric Johnson 5 Public-Key Cryptographic Algorithms ! RSA and Diffie-Hellman ! RSA - Ron Rives, Adi Shamir and Len Adleman at MIT, in 1977. • RSA -

Public Key Cryptography And

PublicPublic KeyKey CryptographyCryptography andand RSARSA Raj Jain Washington University in Saint Louis Saint Louis, MO 63130 [email protected] Audio/Video recordings of this lecture are available at: http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-11/ Washington University in St. Louis CSE571S ©2011 Raj Jain 9-1 OverviewOverview 1. Public Key Encryption 2. Symmetric vs. Public-Key 3. RSA Public Key Encryption 4. RSA Key Construction 5. Optimizing Private Key Operations 6. RSA Security These slides are based partly on Lawrie Brown’s slides supplied with William Stallings’s book “Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice,” 5th Ed, 2011. Washington University in St. Louis CSE571S ©2011 Raj Jain 9-2 PublicPublic KeyKey EncryptionEncryption Invented in 1975 by Diffie and Hellman at Stanford Encrypted_Message = Encrypt(Key1, Message) Message = Decrypt(Key2, Encrypted_Message) Key1 Key2 Text Ciphertext Text Keys are interchangeable: Key2 Key1 Text Ciphertext Text One key is made public while the other is kept private Sender knows only public key of the receiver Asymmetric Washington University in St. Louis CSE571S ©2011 Raj Jain 9-3 PublicPublic KeyKey EncryptionEncryption ExampleExample Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman at MIT RSA: Encrypted_Message = m3 mod 187 Message = Encrypted_Message107 mod 187 Key1 = <3,187>, Key2 = <107,187> Message = 5 Encrypted Message = 53 = 125 Message = 125107 mod 187 = 5 = 125(64+32+8+2+1) mod 187 = {(12564 mod 187)(12532 mod 187)... (1252 mod 187)(125 mod 187)} mod 187 Washington University in -

CS 255: Intro to Cryptography 1 Introduction 2 End-To-End

Programming Assignment 2 Winter 2021 CS 255: Intro to Cryptography Prof. Dan Boneh Due Monday, March 1st, 11:59pm 1 Introduction In this assignment, you are tasked with implementing a secure and efficient end-to-end encrypted chat client using the Double Ratchet Algorithm, a popular session setup protocol that powers real- world chat systems such as Signal and WhatsApp. As an additional challenge, assume you live in a country with government surveillance. Thereby, all messages sent are required to include the session key encrypted with a fixed public key issued by the government. In your implementation, you will make use of various cryptographic primitives we have discussed in class—notably, key exchange, public key encryption, digital signatures, and authenticated encryption. Because it is ill-advised to implement your own primitives in cryptography, you should use an established library: in this case, the Stanford Javascript Crypto Library (SJCL). We will provide starter code that contains a basic template, which you will be able to fill in to satisfy the functionality and security properties described below. 2 End-to-end Encrypted Chat Client 2.1 Implementation Details Your chat client will use the Double Ratchet Algorithm to provide end-to-end encrypted commu- nications with other clients. To evaluate your messaging client, we will check that two or more instances of your implementation it can communicate with each other properly. We feel that it is best to understand the Double Ratchet Algorithm straight from the source, so we ask that you read Sections 1, 2, and 3 of Signal’s published specification here: https://signal. -

Choosing Key Sizes for Cryptography

information security technical report 15 (2010) 21e27 available at www.sciencedirect.com www.compseconline.com/publications/prodinf.htm Choosing key sizes for cryptography Alexander W. Dent Information Security Group, University Of London, Royal Holloway, UK abstract After making the decision to use public-key cryptography, an organisation still has to make many important decisions before a practical system can be implemented. One of the more difficult challenges is to decide the length of the keys which are to be used within the system: longer keys provide more security but mean that the cryptographic operation will take more time to complete. The most common solution is to take advice from information security standards. This article will investigate the methodology that is used produce these standards and their meaning for an organisation who wishes to implement public-key cryptography. ª 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction being compromised by an attacker). It also typically means a slower scheme. Most symmetric cryptographic schemes do The power of public-key cryptography is undeniable. It is not allow the use of keys of different lengths. If a designer astounding in its simplicity and its ability to provide solutions wishes to offer a symmetric scheme which provides different to many seemingly insurmountable organisational problems. security levels depending on the key size, then the designer However, the use of public-key cryptography in practice is has to construct distinct variants of a central design which rarely as simple as the concept first appears. First one has to make use of different pre-specified key lengths. -

Basics of Digital Signatures &

> DOCUMENT SIGNING > eID VALIDATION > SIGNATURE VERIFICATION > TIMESTAMPING & ARCHIVING > APPROVAL WORKFLOW Basics of Digital Signatures & PKI This document provides a quick background to PKI-based digital signatures and an overview of how the signature creation and verification processes work. It also describes how the cryptographic keys used for creating and verifying digital signatures are managed. 1. Background to Digital Signatures Digital signatures are essentially “enciphered data” created using cryptographic algorithms. The algorithms define how the enciphered data is created for a particular document or message. Standard digital signature algorithms exist so that no one needs to create these from scratch. Digital signature algorithms were first invented in the 1970’s and are based on a type of cryptography referred to as “Public Key Cryptography”. By far the most common digital signature algorithm is RSA (named after the inventors Rivest, Shamir and Adelman in 1978), by our estimates it is used in over 80% of the digital signatures being used around the world. This algorithm has been standardised (ISO, ANSI, IETF etc.) and been extensively analysed by the cryptographic research community and you can say with confidence that it has withstood the test of time, i.e. no one has been able to find an efficient way of cracking the RSA algorithm. Another more recent algorithm is ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm), which is likely to become popular over time. Digital signatures are used everywhere even when we are not actually aware, example uses include: Retail payment systems like MasterCard/Visa chip and pin, High-value interbank payment systems (CHAPS, BACS, SWIFT etc), e-Passports and e-ID cards, Logging on to SSL-enabled websites or connecting with corporate VPNs. -

Research Notices

AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Research in Collegiate Mathematics Education. V Annie Selden, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Ed Dubinsky, Kent State University, OH, Guershon Hare I, University of California San Diego, La jolla, and Fernando Hitt, C/NVESTAV, Mexico, Editors This volume presents state-of-the-art research on understanding, teaching, and learning mathematics at the post-secondary level. The articles are peer-reviewed for two major features: (I) advancing our understanding of collegiate mathematics education, and (2) readability by a wide audience of practicing mathematicians interested in issues affecting their students. This is not a collection of scholarly arcana, but a compilation of useful and informative research regarding how students think about and learn mathematics. This series is published in cooperation with the Mathematical Association of America. CBMS Issues in Mathematics Education, Volume 12; 2003; 206 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3302-2; List $49;AII individuals $39; Order code CBMATH/12N044 MATHEMATICS EDUCATION Also of interest .. RESEARCH: AGul<lelbrthe Mathematics Education Research: Hothomatldan- A Guide for the Research Mathematician --lllll'tj.M...,.a.,-- Curtis McKnight, Andy Magid, and -- Teri J. Murphy, University of Oklahoma, Norman, and Michelynn McKnight, Norman, OK 2000; I 06 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-20 16-8; List $20;AII AMS members $16; Order code MERN044 Teaching Mathematics in Colleges and Universities: Case Studies for Today's Classroom Graduate Student Edition Faculty -

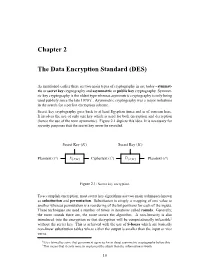

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

A Decade of Lattice Cryptography

Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/0400000074 A Decade of Lattice Cryptography Chris Peikert Computer Science and Engineering University of Michigan, United States Boston — Delft Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/0400000074 Foundations and Trends R in Theoretical Computer Science Published, sold and distributed by: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 1024 Hanover, MA 02339 United States Tel. +1-781-985-4510 www.nowpublishers.com [email protected] Outside North America: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 179 2600 AD Delft The Netherlands Tel. +31-6-51115274 The preferred citation for this publication is C. Peikert. A Decade of Lattice Cryptography. Foundations and Trends R in Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 283–424, 2014. R This Foundations and Trends issue was typeset in LATEX using a class file designed by Neal Parikh. Printed on acid-free paper. ISBN: 978-1-68083-113-9 c 2016 C. Peikert All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publishers. Photocopying. In the USA: This journal is registered at the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. Authorization to photocopy items for in- ternal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by now Publishers Inc for users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC). The ‘services’ for users can be found on the internet at: www.copyright.com For those organizations that have been granted a photocopy license, a separate system of payment has been arranged. -

The Best Nurturers in Computer Science Research

The Best Nurturers in Computer Science Research Bharath Kumar M. Y. N. Srikant IISc-CSA-TR-2004-10 http://archive.csa.iisc.ernet.in/TR/2004/10/ Computer Science and Automation Indian Institute of Science, India October 2004 The Best Nurturers in Computer Science Research Bharath Kumar M.∗ Y. N. Srikant† Abstract The paper presents a heuristic for mining nurturers in temporally organized collaboration networks: people who facilitate the growth and success of the young ones. Specifically, this heuristic is applied to the computer science bibliographic data to find the best nurturers in computer science research. The measure of success is parameterized, and the paper demonstrates experiments and results with publication count and citations as success metrics. Rather than just the nurturer’s success, the heuristic captures the influence he has had in the indepen- dent success of the relatively young in the network. These results can hence be a useful resource to graduate students and post-doctoral can- didates. The heuristic is extended to accurately yield ranked nurturers inside a particular time period. Interestingly, there is a recognizable deviation between the rankings of the most successful researchers and the best nurturers, which although is obvious from a social perspective has not been statistically demonstrated. Keywords: Social Network Analysis, Bibliometrics, Temporal Data Mining. 1 Introduction Consider a student Arjun, who has finished his under-graduate degree in Computer Science, and is seeking a PhD degree followed by a successful career in Computer Science research. How does he choose his research advisor? He has the following options with him: 1. Look up the rankings of various universities [1], and apply to any “rea- sonably good” professor in any of the top universities. -

Algebraic Pseudorandom Functions with Improved Efficiency from the Augmented Cascade*

Algebraic Pseudorandom Functions with Improved Efficiency from the Augmented Cascade* DAN BONEH† HART MONTGOMERY‡ ANANTH RAGHUNATHAN§ Department of Computer Science, Stanford University fdabo,hartm,[email protected] September 8, 2020 Abstract We construct an algebraic pseudorandom function (PRF) that is more efficient than the classic Naor- Reingold algebraic PRF. Our PRF is the result of adapting the cascade construction, which is the basis of HMAC, to the algebraic settings. To do so we define an augmented cascade and prove it secure when the underlying PRF satisfies a property called parallel security. We then use the augmented cascade to build new algebraic PRFs. The algebraic structure of our PRF leads to an efficient large-domain Verifiable Random Function (VRF) and a large-domain simulatable VRF. 1 Introduction Pseudorandom functions (PRFs), first defined by Goldreich, Goldwasser, and Micali [GGM86], are a fun- damental building block in cryptography and have numerous applications. They are used for encryption, message integrity, signatures, key derivation, user authentication, and many other cryptographic mecha- nisms. Beyond cryptography, PRFs are used to defend against denial of service attacks [Ber96, CW03] and even to prove lower bounds in learning theory. In a nutshell, a PRF is indistinguishable from a truly random function. We give precise definitions in the next section. The fastest PRFs are built from block ciphers like AES and security is based on ad-hoc inter- active assumptions. In 1996, Naor and Reingold [NR97] presented an elegant PRF whose security can be deduced from the hardness of the Decision Diffie-Hellman problem (DDH) defined in the next section. -

Dan Boneh Cryptography Professor, Professor of Electrical Engineering and Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Computer Science

Dan Boneh Cryptography Professor, Professor of Electrical Engineering and Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Computer Science CONTACT INFORMATION • Administrator Ruth Harris - Administrative Associate Email [email protected] Tel (650) 723-1658 Bio BIO Professor Boneh heads the applied cryptography group and co-direct the computer security lab. Professor Boneh's research focuses on applications of cryptography to computer security. His work includes cryptosystems with novel properties, web security, security for mobile devices, and cryptanalysis. He is the author of over a hundred publications in the field and is a Packard and Alfred P. Sloan fellow. He is a recipient of the 2014 ACM prize and the 2013 Godel prize. In 2011 Dr. Boneh received the Ishii award for industry education innovation. Professor Boneh received his Ph.D from Princeton University and joined Stanford in 1997. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS • Professor, Computer Science • Professor, Electrical Engineering • Senior Fellow, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies HONORS AND AWARDS • ACM prize, ACM (2015) • Simons investigator, Simons foundation (2015) • Godel prize, ACM (2013) • IACR fellow, IACR (2013) 4 OF 6 PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION • PhD, Princeton (1996) LINKS • http://crypto.stanford.edu/~dabo: http://crypto.stanford.edu/~dabo Page 1 of 2 Dan Boneh http://cap.stanford.edu/profiles/Dan_Boneh/ Teaching COURSES 2021-22 • Computer and Network Security: CS 155 (Spr) • Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies: CS 251 (Aut) • -

Remote Side-Channel Attacks on Anonymous Transactions

Remote Side-Channel Attacks on Anonymous Transactions Florian Tramer and Dan Boneh, Stanford University; Kenny Paterson, ETH Zurich https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity20/presentation/tramer This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium. August 12–14, 2020 978-1-939133-17-5 Open access to the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX. Remote Side-Channel Attacks on Anonymous Transactions Florian Tramèr∗ Dan Boneh Kenneth G. Paterson Stanford University Stanford University ETH Zürich Abstract Bitcoin’s transaction graph. The same holds for many other Privacy-focused crypto-currencies, such as Zcash or Monero, crypto-currencies. aim to provide strong cryptographic guarantees for transaction For those who want transaction privacy on a public confidentiality and unlinkability. In this paper, we describe blockchain, systems like Zcash [45], Monero [47], and several side-channel attacks that let remote adversaries bypass these others offer differing degrees of unlinkability against a party protections. who records all the transactions in the network. We focus We present a general class of timing side-channel and in this paper on Zcash and Monero, since they are the two traffic-analysis attacks on receiver privacy. These attacks en- largest anonymous crypto-currencies by market capitaliza- able an active remote adversary to identify the (secret) payee tion. However our approach is more generally applicable, and of any transaction in Zcash or Monero. The attacks violate we expect other anonymous crypto-currencies to suffer from the privacy goals of these crypto-currencies by exploiting similar vulnerabilities. side-channel information leaked by the implementation of Zcash and Monero use fairly advanced cryptographic different system components.