Acta 91.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

-

Development of Passenger Train Transport in the Brno Urban Region Between 1980 and 2010

ISSN 1426-5915 e-ISSN 2543-859X 20(2)/2017 Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG 2017, 20(2), 43-56 DOI 10.4467/2543859XPKG.17.010.7392 DeveloPmenT of PassenGer Train TransPorT in The Brno urBan reGion BeTween 1980 anD 2010 Rozwój pasażerskiego transportu kolejowego w rejonie miejskim Brna w latach 1980-2010 Jiří Dujka (1), Daniel seidenglanz (2) (1) Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University Brno, Kotlářská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic e-mail: [email protected] (2) Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University Brno, Kotlářská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Dujka J., Seidenglanz D., 2017, Development of passenger train transport in the Brno urban region between 1980 and 2010, Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG, 20(2), 43-56. abstract: The lengthy timespan of thirty years shall be a playground of many changes and variations in all spheres of social life and technical world. Public transportation is an integral part of both mentioned fields and co-operates with their changes. The urban region of Brno, the second largest city in the Czech Republic, is the region with a strong core (city of Brno) and thus it is a rail hub as well. Since 1980, the whole urban region underwent several changes in an industrial structure (from industrialization and preference of heavy industries to de-industrialization and dominance of services), a social organization (transition from industrial to post-industrial patterns of life, from urbanization to suburbanization and subruralization), an arrangement of the settlement system (from densely-populated estates on the edges of the city to suburbanization) and transportation patterns (moving from public transportation to individual road transportation). -

1 Česká Republika

Česká republika - Okresní soud Brno-venkov Spr 1411/2018 Brno dne 13. 11. 2018 ROZVRH PRÁCE Okresního soudu Brno-venkov pro rok 2019 ___________________________________________________________________________ Pružná pracovní doba : Základní pracovní doba : 8.00 – 14.00 hodin Volitelná pracovní doba : 6.00 – 8.00 hodin, 14.00 – 18.00 hodin Doba pro styk s veřejností : u předsedkyně soudu středa od 9.00 – 11.00 hod., od 13.00 – 15.00 hodin u místopředsedy soudu úterý od 9.00 – 11.00 hod., od l3.00 – 15.00 hodin informační oddělení pondělí, úterý, čtvrtek od 8.00 – 15.30 hodin a podatelna středa od 8,00 – 16.30 hodin pátek od 8,00 – 14.30 hodin ledaže by opatřením předsedkyně soudu byla ad hoc na konkrétní den stanovena úřední doba jinak. Předsedkyně soudu : JUDr. Ivana Losová vykonává státní správu okresního soudu dle § 127 zákona č. 6/2002 Sb. v platném znění, řídí a kontroluje činnost na úseku občanskoprávním a opatrovnickém a vyřizuje stížnosti na těchto úsecích, vyřizuje žádosti o informace dle zákona č. 106/1999 Sb., v platném znění na úseku občanskoprávním a opatrovnickém, je příkazcem operací ve smyslu zákona č. 320/2001 Sb. a Instrukce předsedkyně Okresního soudu Brno-venkov Spr 1467/2004 pro všechny operace Místopředsedkyně soudu : Mgr. Lenka Šebestová zastupuje v době nepřítomnosti předsedkyni soudu, řídí a kontroluje činnost na úseku trestním, exekučním, dědickém a úschov, vyřizuje stížnosti na těchto úsecích, provádí výkon státního dohledu nad činností soudních exekutorů a notářů, vyřizuje žádosti o informace dle zákona č. 106/1999 Sb., v platném znění, na úseku trestním, exekučním, dědickém a úschov, je příkazcem operací v případě nepřítomnosti předsedkyně soudu ve smyslu zákona č. -

Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Klárov 3 Workplace Barrandov Branch Brno Erbenova 348, P

Headquarters | Central Laboratory | Applied & Regional Regional Office | Applied & Regional Geochemistry | Geology | Laboratory of Cor Shed | Geology | Publishing Economic Geology Organic Geochemistry | Bookshop Dpt. | IT Centre | Archive | GIS & DB | Collections | Library | Library & Archive | Bookshop Bookshop Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey Klárov 3 Workplace Barrandov Branch Brno Erbenova 348, P. O. Box 65 118 21 PRAHA 1 Geologická 6 Leitnerova 22 790 01 JESENÍK Phone: +420 257 089 411 152 00 PRAHA 5 658 69 BRNO Phone/fax: +420 584 412 081 Czech Geological Survey Fax: +420 257 531 376 Phone: +420 251 085 111 Phone: +420 543 429 200 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +420 251 818 748 Fax: +420 543 212 370 Annual Review 2004 Geological research & mapping Geochemistry & environmental studies Mineral resources & mining impact Applied geology & natural hazards Management & delivery of geodata Laboratory services & research International activities & cooperation For other contacts and information please see p. 33 or visit us at: ISBN 80-7075-652-7 www.geology.cz oobalkabalka rrevieweview vvnitrninitrni sstrany.inddtrany.indd 2 55.10.2005.10.2005 116:22:536:22:53 www.geology.cz Czech Geological Survey Czech Geological Survey | Organizational Structure 2004 Contents since 1919 Foreword 1 Mission Geological research & mapping 2 • collecting, assessment and dissemination of data on the geological composition, mineral resources and natural Geochemistry & environmental studies 6 risks of -

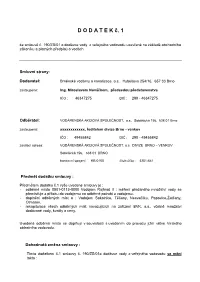

D O D a T E K Č

D O D A T E K č. 1 ke smlouvě č. 190/ZS/01 o dodávce vody z veřejného vodovodu uzavřené na základě obchodního zákoníku a platných předpisů o vodách. Smluvní strany: Dodavatel: Brněnské vodárny a kanalizace, a.s., Hybešova 254/16, 657 33 Brno zastoupené: Ing. Miroslavem Nováčkem, předsedou představenstva IČO : 46347275 DIČ : 288 - 46347275 Odběratel: VODÁRENSKÁ AKCIOVÁ SPOLEČNOST, a.s., Soběšická 156, 638 01 Brno zastoupená: xxxxxxxxxxxx, ředitelem divize Brno - venkov IČO : 49455842 DIČ : 290 - 49455842 zasílací adresa: VODÁRENSKÁ AKCIOVÁ SPOLEČNOST, a.s. DIVIZE BRNO – VENKOV Soběšická 156, 638 01 BRNO bankovní spojení: KB 0100 číslo účtu : 3201-641 Předmět dodatku smlouvy : Předmětem dodatku č.1 výše uvedené smlouvy je : - odběrné místo 0501-0113-0000 Vodojem Rajhrad II : měření předaného množství vody se přemísťuje z přítoku do vodojemu na odběrné potrubí z vodojemu. - doplnění odběrných míst o : Vodojem Sokolnice, Těšany, Nesvačilku, Popovice,Žatčany, Otmarov. - rekapitulace všech odběrných míst navazujících na zařízení BVK, a.s., včetně množství dodávané vody, kvality a ceny. Uvedená odběrná místa se doplňují v souvislosti s uvedením do provozu jižní větve Vírského oblastního vodovodu. Dohodnutá změna smlouvy : Tímto dodatkem č.1 smlouvy č. 190/ZS/01o dodávce vody z veřejného vodovodu se mění takto : 1. II. odběrné místo vody 1. 0501-0097-0000 Vodojem ŽELEŠICE 2. 0501-0117-0000 Vodojem RAJHRAD II 3. 0501-0112-0000 Výtlak čerpací stanice pro vodojem HAJANY umístěné ve vodojemu RAJHRAD I 4. 0501-0085-0000 Bílovice, v šachtě ulice Obřanská 5. 0501-0057-0000 Šlapanice, v šachtě ulice Mikulčická 6. 0501-0115-0000 Malhostovice (z VOV) – šachta 7. -

Žádost O Zveřejnění Veřejné Vyhlášky Opatření Obecné Povahy, Kterým Se Zřizuje Ochranné Pásmo Radiolokátoru Sokolnice

Sekce nakládání s majetkem Ministerstva obrany odbor ochrany územních zájmů a státního odborného dozoru oddělení státního dozoru Olomouc Dobrovského 6, Olomouc, PSČ 771 11, datová schránka x2d4xnx Váš dopis zn. Ze dne: Naše čj. MO 309116/2020-1150Ol Sp. zn. SpMO 26814-193/2019-1216Ol Vyřizuje Ing. Bc. Dagmar Geratová podle rozdělovníku Telefon 973 401 522 Mobil 602 204 260 E-mail: [email protected] Datum: 9. listopadu 2020 Žádost o zveřejnění veřejné vyhlášky opatření obecné povahy, kterým se zřizuje ochranné pásmo radiolokátoru Sokolnice Ministerstvo obrany jako speciální stavební úřad (dále jen „úřad“) podle § 15 odst. 1 písm. a) zákona číslo 183/2006 Sb., o územním plánování a stavebním řádu (stavební zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů (dále jen "stavební zákon"), v souladu s ustanovením § 43 zákona číslo 49/1997 Sb., o civilním letectví a o změně a doplnění zákona číslo 455/1991 Sb., o živnostenském podnikání (živnostenský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů (dále jen "zákon o civilním letectví"), pro vojenská letiště, vojenské letecké stavby a jejich ochranná pásma, a v souladu s ustanovením § 173 zákona číslo 500/2004 Sb., správní řád (dále jen „správní řád“) zřizuje podle § 37 zákona o civilním letectví ochranné pásmo vojenského leteckého pozemního zařízení radiolokátoru Sokolnice (dále jen „OP“). Počínaje dnem 23. 11. 2020 do 8. 12. 2020 je možno se seznámit s úplným zněním veřejné vyhlášky opatření obecné povahy (dále jen „OOP“), včetně grafických příloh (Ochranná pásma radiolokátoru Sokolnice - Dokumentace ochranných pásem, Příloha č. 1 – OP Sokolnice, celková situace, Příloha č. 2 - OP Sokolnice, sektor A a B do 5000 m, Příloha č. 3 - OP Sokolnice, sektor A a B do 30 000 m pro posouzení vlivu větrných elektráren) dálkovým přístupem na elektronické úřední desce Ministerstva obrany. -

Abecední Seznam

INTEGROVANÝ DOPRAVNÍ SYSTÉM JIHOMORAVSKÉHO KRAJE ABECEDNÍ SEZNAM OBCE DLE ZÓN ZASTÁVKY MIMO ZÓNY 100 A 101 ZASTÁVKY V ZÓNÁCH 100 A 101 Stav k 11. 12. 2016 Informační telefon: +420 5 4317 4317 Verze 161211 Zařazení obcí do zón IDS JMK Zóna Obec Zóna Obec Zóna Obec Zóna Obec 225 Adamov 650 Brumovice 286 Dolní Poříčí [Křetín] 468 Horní Kounice 447 Alexovice [Ivančice] 575 Břeclav 280 Dolní Smržov [Letovice] 235 Horní Lhota [Blansko] 652 Archlebov 561 Březí 552 Dolní Věstonice 340 Horní Loučky 220 Babice nad Svitavou (obec) 220 Březina (u Křtin) 695 Domanín 286 Horní Poříčí 215 Babice nad Svitavou (žel. s.) 330 Březina (u Tišnova) 370 Domanín [Bystřice n. Pernštejnem] 290 Horní Smržov 425 Babice u Rosic 290 Březina (u V. Opatovic) 430 Domašov 270 Horní Štěpánov 275 Babolky [Letovice] 295 Březová nad Svitavou 831 Domčice [Horní Dunajovice] 552 Horní Věstonice 275 Bačov [Boskovice] 550 Břežany 255 Doubravice nad Svitavou 235 Hořice [Blansko] 810 Bantice 645 Bučovice 350 Doubravník 720 Hostěnice 552 Bavory 447 Budkovice [Ivančice] 260 Drahany 459 Hostěradice 257 Bedřichov 260 Buková 350 Drahonín 610 Hostěrádky-Rešov 610 Bedřichovice [Šlapanice] 662 Bukovany 581 Drasenhofen (A) 845 Hostim 832 Běhařovice 247 Bukovice 320 Drásov 750 Hoštice-Heroltice 350 Běleč 220 Bukovina 730 Dražovice 660 Hovorany 260 Benešov 220 Bukovinka 652 Dražůvky 560 Hrabětice 280 Bezděčí [Velké Opatovice] 735 Bukovinka (Říčky, hájenka) 551 Drnholec 330 Hradčany 815 Bezkov 562 Bulhary 256 Drnovice (u Lysic) 839 Hrádek 215 Bílovice nad Svitavou 246 Býkovice 730 Drnovice (u Vyškova) 265 Hrádkov [Boskovice] 447 Biskoupky 297 Bystré 877 Drosendorf (A) 477 Hrotovice 843 Biskupice-Pulkov 370 Bystřice nad Pernštejnem 280 Drválovice [Vanovice] 945 Hroznová Lhota 857 Bítov 695 Bzenec 750 Drysice 955 Hrubá Vrbka 835 Blanné 280 Cetkovice 917 Dubňany 447 Hrubšice [Ivančice] 235 Blansko 815 Citonice 457 Dukovany 912 Hrušky (u Břeclavi) 232 Blansko (Skalní Mlýn) 277 Crhov 467 Dukovany (EDU) 620 Hrušky (u Slavkova) 945 Blatnice pod Sv. -

A LANDSCAPE-ECOLOGICAL STUDY Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Methodology

BRNO AND ITS SURROUNDINGS: A LANDSCAPE-ECOLOGICAL STUDY Jaromír Demek, Marek Havlí ček, Peter Mackov čin, Tereza Stránská Silva Tarouca Research Institute for Landscape and Ornamental Gardening (VÚKOZ) Pr ůhonice, Department of Landscape Ecology Brno, Lidická 25/27, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic, email:[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] , [email protected] Abstract Authors used historical maps from the period 1760 to 2005 for the study of spatial development of the city of Brno and its surroundings (Czech Republic). The City of Brno is the second largest urban agglomeration in the Czech Republic. Historical topographic maps are very useful source of information for the landscape-ecological studies of such urbanized and rural landscapes. Digital processing of maps in GIS milieu enables a high-quality assessment of changes occurring in the landscape. An interesting result of the study is the fact that in spite of the location of the region under study within the hinterland of the city of Brno, 60% of the territory shows stability in the monitored time interval. Multiple land use changes were observed on the peripheries of the urban agglomeration. Less stable are also floodplain landscapes. Key words : city of Brno, urban landscapes, impact of the city development on landscapes in its hinterland, use of historical maps in landscape-ecological studies in GIS environment 1. Introduction The Department of landscape ecology at VÚKOZ is engaged with the development of Czech landscape in the last 250 years on the basis of studying data contained in large-scale digitalized historical topographic maps in GIS milieu. -

I/03.15 Návrh Uspořádání Dálniční a Silniční Sítě

tpÆnovice Závist jezd u ¨ernØ Hory II Krasová / 7 8 387 7 VARIANTA S.9.3 3 Lomnièka 37 / I/ I II I I /38 II / 5 Vechovice 374 Doln LouŁky eleznØ Skalièka Milonice Kotvrdovice II/389 Blansko II/373 D`LNI¨N˝ A SILNI¨N˝ S˝ II/379 Tinov Vilémovice Krásensko Laany STAV NÁVRH 9 II/37 Jedovnice I / PłedklÆteł 43 DÁLNICE TRASA DÁLNICE 9 Podom Drásov II/37 NelepeŁ-ernøvka Lipùvka Senetáøov 43 / II/379 I MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA ebrov-Katełina su II/379 II/379 NA DÁLNICI NA DÁLNICI Hradèany Malhostovice Rudice Svinoice SILNICE I. T˝DY TRASA KAPACITNÍ KOMUNIKACE Vohanèice Bøezina II Ruprechtov /385 Olomuèany I I/37 9 ¨ebn TUNEL NA SILNICI I. T˝DY MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA Vranov II / 37 II / 386 385 II/ 3 NA KAPACITNÍ KOMUNIKACI Heroltice Sentice Habrùvka Køtiny Jekovice MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA TRASA DAL˝ KOMUNIKACE Kuøim Bukovinka NA SILNICI I. T˝DY II/38 Lelekovice Bukovina 5 SILNICE II. T˝DY MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA Chudèice II/386 Adamov I/43 NA DAL˝ KOMUNIKACI II / MoravskØ Knnice 3 MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA KE ZRUEN˝ Èeská 74 Marov NA SILNICI II. T˝DY Babice nad Svitavou Bøezina LaÆnky VeverskÆ Btka SILNICE III. T˝DY A M˝STN˝ KOMUNIKACE RaŁice-Pstovice Jinaèovice MIMOROVOV` KIOVATKA II /386 cmanice Javùrek Ochoz u Brna Rozdrojovice Nemojany NA OSTATNÍCH KOMUNIKACÍCH /383 II II/383 Olany Kanice Blovice nad Svitavou II I / /38 4 Hostnice 3 VeverskØ Knnice 4 D Hvozdec 1 386 II/ 640 II/ 374 / II Habrovany 373 II/ Mokrá-Horákov PODKLAD Łany l/42 I Pozoøice l/602 HRANICE PLOCHY PRO PROVEN˝ ZEMN˝ STUDI˝ DLE ZR JMK 42 Ostrovaèice II l/ /384 642 ll/ Sivice -

Transformace Regionu SO ORP Po Roce 1989 Na Příkladu SO ORP Kuřim Se Zaměřením Na Obyvatelstvo a Sídla

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA GEOGRAFICKÝ ÚSTAV Transformace regionu SO ORP po roce 1989 na příkladu SO ORP Kuřim se zaměřením na obyvatelstvo a sídla Bakalářská práce Petra Zavřelová Vedoucí práce: doc. RNDr. Milan Jeřábek, Ph.D. BRNO 2015 Bibliografický záznam Autor: Petra Zavřelová Přírodovědecká fakulta, Masarykova univerzita Geografický ústav Název práce: Transformace regionu SO ORP po roce 1989 na příkladu SO ORP Kuřim se zaměřením na obyvatelstvo a sídla Studijní program: Geografie a kartografie Studijní obor: Geografie Vedoucí práce: doc. RNDr. Milan Jeřábek, Ph.D. Akademický rok: 2014/2015 Počet stran: 55+1 Klíčová slova: Transformace regionu, SO ORP Kuřim, dojíţďka, bytová výstavba Bibliografic Entry Author: Petra Zavřelová Faculty of Science, Masaryk University Department of Geography Title of Thesis: The transformation of the region (locality) in 1989 for example SO ORP Kuřim focusing on population and settlements Degree Programme: Geography and Cartography Field of Study: Geography Supervisor: doc. RNDr. Milan Jeřábek, Ph.D. Academic Year: 2014/2015 Number of Pages: 55+1 Keywords: Transformation of the region, SO ORP Kuřim, commuting, housing Abstrakt Závěrečná práce zkoumá vývoj vybraných charakteristik v SO ORP Kuřim po roce 1989. Je rozdělena na dvě části, první se věnuje analýze dojíţďky za prací a do škol, druhá je zaměřena na změny a trendy v bytové výstavbě. Dílčí výsledky jsou porovnávány s jinými administrativními jednotkami a na závěr je shrnuto, do jaké míry ke změnám došlo a zda byly stanovené hypotézy potvrzeny nebo vyvráceny. Kvantitativní část výzkumu představoval sběr dat nejčastěji ze sčítání, popřípadě z dalších zdrojů a poté jsou některé výsledky doloţeny i terénním průzkumem nebo satelitními snímky. -

Mikroregion Kahan

WWW.MIKROREGIONKAHAN.CZ Hutni osada 14 664 84, Zastavka Tel.: +420 546 429 048 Fax: +420 546 429 048 E-mail: [email protected] MIKROREGION KAHAN Dobrovolný svazek obcí Mikroregion Kahan byl založen v roce 2000 na základě vůle obcí za účelem: Ochrana životního prostředí Společný postup při dosahování ekologické stability Koordinace významných investičních akcí Koordinace obecních územních plánů a územní plánování v regionálním měřítku Slaďování zájmů a činností místních samospráv Vytváření, zmnožování a správa společného majetku svazku Zastupování členů svazku při jednání o společných věcech s třetími osobami Zajišťování a vedení předepsané písemné, výkresové, technické agendy jednotlivých společných akcí Propagace svazku a jeho území MIKROREGION KAHAN MIKROREGION KAHAN 13 členských obcí, 20 000 obyvatel, rozloha 10 500 ha Babice u Rosic Kratochvilka Lukovany Ostrovačice Příbram na Moravě Rosice Říčany Tetčice Újezd u Rosic Vysoké Popovice Zakřany Zastávka Zbýšov MIKROREGION KAHAN Partneři Muzeum průmyslových železnic Vlastivědný spolek Rosicko-Oslavanska Skupina ČEZ Partnerství, o.p.s. Mikroregion Velká Fatra Mighty Shake Zastávka KTS EKOLOGIE MAS Brána Brněnska MIKROREGION KAHAN KTS EKOLOGIE Funkční příklad kvalitní meziobecní spolupráce MIKROREGION KAHAN MIKROREGION KAHAN Společnost KTS EKOLOGIE s.r.o. byla založena 14. října 2008 a vznikla zápisem do OR vedeného Krajským soudem v Brně dne 12. listopadu 2008. Zapsaným sídlem společnosti je Hutní osada 14, 664 84 Zastávka. Předmět činnosti: – -

Dálnice D52 Brno, Jižní Tangenta Včetně Zkapacitnění D2

Dálnice D52 Brno, Jižní tangenta včetně zkapacitnění D2 Ostopovice 41 stavba I/41 a I/42 Brno VMO centrum výhled dle ÚP Brno Dálnice D52 Bratislavská radiála INFORMAČNÍ LETÁK, stav k 09/2021 Rosice Slavkov stavba centrum 1 Šlapanice u Brna Ivančice Brno, Jižní tangenta včetně zkapacitnění D2 Praha Bučovice Střelice stavba D1 01311 Brno jih – Brno východ III/15273 stavba D1 01191.C Brno centrum – Brno jih Moravský Brno jih Ostrava Krumlov III/15275 stavba D1 01191.B MÚK Brno západ – MÚK Brno centrum stavba D1 01191.A MÚK Brno jih Židlochovice III/15275 Moravany Pohořelice III/15275 III/15268 380 Brněnské III/15277 IKEA Ivanovice Hustopeče III/15276 Brno III/15278 III/15281 Radostice Nebovidy Dolní Heršpice 2 380 Mikulov Holásky Břeclav Přízřenice 52 III/15280 Chrlice I III/15282 Chrlice Modřice III/15278 152 Želešice 152 152 Hajany Chrlice II Ořechov 52 řešená stavba jiné stavby III/41614 III/00219 Popovice Rajhrad Rebešovice 2 0 1 2 km stavba D52 rozšíření odpočívky Rajhrad 425 III/41610 Otmarov Geografická data poskytl VGHMÚř Dobruška, © MO ČR, 2013 III/41617 52 Rajhradice B27 III/39513 Rajhrad Syrovice III/41614 Mělčany Syrovice III/42510 III/15266 Wien A Holasice Bratislava SK Bratčice Opatovice Brno, Jižní tangenta včetně zkapacitnění D2 Dálnice D52 DOPRAVNÍ VÝZNAM STAVBY UMÍSTĚNÍ A POPIS STAVBY Dálnice D52 spojuje Brno, resp. dálnici D1 s Po- V červnu 2015 byla zpracována technická studie, ve Popovic. Trasa končí za odpočívkou Rajhrad. Se sil- hořelicemi, Mikulovem a Rakouskem. Důležitá které byla trasa navržena ve dvou variantách vedení nicí III/39513 bude vybudována MÚK Syrovice, která je i pro spojení Brna se Znojmem.