The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.Documentals, Pel.Lícules, Concerts, Ballet, Teatre

2.DOCUMENTALS, PEL.LÍCULES, CONCERTS, BALLET, TEATRE..... L’aparició del format DVD ha empès a que molts teatres, televisions, productores, etc hagin decidit reeeditar programes que havien contribuït a popularitzar i divulgar diferents aspectes culturals. També permet elaborar documents que en altres formats son prohibitius, per això avui en dia, hi ha molt a on triar. En aquest arxiu trobareu: -- Documentals a) dedicats a Wagner o la seva obra b) dedicats a altres músics, obres, cantants, directors, ... -- Grabacions de concerts i recitals a) D’ obres wagnerianes b) D’ altres obres i compositors -- Pel.lícules que ens acosten al món de la música -- Ballet clàssic -- Teatre clàssic Associació Wagneriana. Apartat postal 1159 Barcelona Http://www. associaciowagneriana.com. [email protected] DOCUMENTALS A) DEDICATS A WAGNER O LA SEVA OBRA 1. “The Golden Ring” DVD: DECCA Film de la BBC que mostre com es va grabar en disc La Tetralogia en 1965, dirigida per Georg Solti. El DVD es centre en la grabació del Götterdämmerung. Molt recomenable 2. Sing Faster. The Stagehands’Ring Cycle. DVD: Docurama Filmat per John Else presenta com es va preparar el montatge de la Tetralogia a San Francisco. Interesant ja que mostra la feina que cal realitzar en diferents àmbits per organitzar un Anell, però malhauradament la producció escenogrficament és bastant dolenta. 3. “Parsifal” DVD: Kultur. Del director Tony Palmer, el que va firmar la biografia deplorable del compositor Wagner, aquest documental ens apropa i allunya del Parsifal de Wagner. Ens apropa en les explicacions de Domingo i ens allunya amb les bestieses de Gutman. Prescindible. B) DEDICATS A ALTRES MÚSICS, OBRES, CANTANTS, DIRECTORS, .. -

Bolshoi Theater

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Dick Caples Tel: 212.221.7909 E-mail: [email protected] Lar Lubovitch awarded the 20th annual prize for best choreography by the Prix Benois de la Danse at the Bolshoi Theater. He is the first head of an American dance company ever to be so honored. New York, NY, May 23, 2012 – Last night at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, Lar Lubovitch was awarded the 20th annual prize for best choreography by the Prix Benois de la Danse. Lubovitch is the first head of an American dance company ever presented with the award. He was honored for his creation of Crisis Variations, which premiered at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York City on November 9, 2011. The work, for seven dancers, is set to a commissioned score by composer Yevgeniy Sharlat, and the score was performed live at its premiere by the ensemble Le Train Bleu, under the direction of conductor Ransom Wilson. To celebrate the occasion, the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company performed the duet from Meadow for the audience of 2,500 at the Bolshoi. The dancers in the duet were Katarzyna Skarpetowska and Brian McGinnis. The laureates for best choreography over the previous 19 years include: John Neumeier, Jiri Kylian, Roland Petit, Angelin Preljocaj, Nacho Duato, Alexei Ratmansky, Boris Eifman, Wayne McGregor, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and Jorma Elo. Other star performers and important international figures from the world of dance received prizes at this year’s award ceremony. In addition to the award for choreography given to Lubovitch, the winners in other categories were: For the best performance by a ballerina: Alina Cojocaru for the role of Julie in “Liliom” at the Hamburg Ballet. -

Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique Free Download

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET: RUSSIAN BALLET TECHNIQUE FREE DOWNLOAD Agrippina Vaganova,A. Chujoy | 175 pages | 01 Jun 1969 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486220369 | English | New York, United States Classical Ballet Technique Vaganova was a student at the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburggraduating in Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique dance professionally with the school's parent company, the Imperial Russian Ballet. Vaganova —not only a great dancer but also the teacher of Galina Ulanova and many others and an unsurpassed theoretician. Balanchine Method dancers must be extremely fit and flexible. Archived from the original on The stem of aplomb is the spine. Refresh and try again. A must Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique for any classically trained dancer. Enlarge cover. Can I view this online? See Article History. Jocelyn Mcgregor rated it liked it May 28, No trivia or quizzes yet. Black London. The most identifiable aspect of the RAD method is the attention to detail when learning the basic steps, and the progression in difficulty is often very slow. En face is the natural direction for the 1st and 2nd positions and generally they remain so. Trivia About Basic Principles This the book that really put the Vaganova method of ballet training on the map-a brave adventure, and a truly important book. Helps a lot during my russian classes. Through the 30 years she spent teaching ballet and pedagogy, Vaganova developed a precise dance technique and system of instruction. Rather than emphasizing perfect technique, ballet dancers of the French School focus instead on fluidity and elegance. -

Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova

Compiled by Irina Kuzmina Marina Medkova English version Olga Perevezentseva Dmitry Osipenko Digital version Dmitry Osipenko Graphic Design Lilia Garifullina Theatre Union of the Russian Federation Strastnoy Blvd., 10, Moscow, 107031, Russia Tel: +7 (495) 6502846 Fax: +7 (495) 6500132 e-mail: [email protected] www.stdrf.ru Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova. Moscow, Theatre Union of Russia, April 2016 A reference book with information about the structure, locations, addresses and contacts of organisers of theatre festivals of all disciplines in the Russian Federation as of April, 2016. The publication is addressed to theatre professionals, bodies managing culture institutions of all levels, students and lecturers of theatre educational institutions. In Russian and English. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. The publisher is very thankful to all the festival managers who are being in constant contact with Theatre Union of Russia and who continuously provide updated information about their festivals for publication in electronic and printed versions of this Guide. The publisher is particularly grateful for the invaluable collaboration efforts of Sergey Shternin of Theatre Information Technologies Centre, St. Petersburg, Ekaterina Gaeva of S.I.-ART (Theatrical Russia Directory), Moscow, Dmitry Rodionov of Scena (The Stage) Magazine and A.A.Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum. 3 editors' notes We are glad to introduce you to the third edition of the Russian Theatre Festival Guide. -

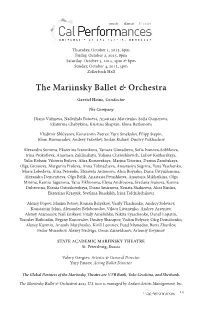

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria

Friday 24 April Sadler’s Wells Digital Stage An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria Natalia Osipova is a major star in the dance world. She started formal ballet training at age 8, joining the Bolshoi Ballet at age 18 and dancing many of the art form’s biggest roles. After leaving the Bolshoi in 2011, she joined American Ballet Theatre as a guest dancer and later the Mikhailovsky Ballet. She joined The Royal Ballet as a principal in 2013 after her guest appearance in Swan Lake. This showcase comprises of three of Natalia’s most captivating appearances on the Sadler’s Wells stage. Featuring Valse Triste, specially created for Natalia and American Ballet Theatre principal David Hallberg by Alexei Ratmansky, and the beautifully emotive Ave Maria by Japanese choreographer Yuka Oishi set to the music of Schubert, both of which premiered in 2018 at Sadler’s Wells’ as part of Pure Dance. The programme will also feature Qutb, a uniquely complex and intimate work by Sadler’s Wells Associate Artist Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, which premiered in 2016 as part of Natalia’s first commission alongside works by Arthur Pita and fellow Associate Artist Russell Maliphant. VALSE TRISTE, PURE DANCE 2018 Natalia Osipova Russian dancer Natalia Osipova is a Principal of The Royal Ballet. She joined the Company as a Principal in autumn 2013, after appearing as a Guest Artist the previous Season as Odette/Odile (Swan Lake) with Carlos Acosta. Her roles with the Company include Giselle, Kitri (Don Quixote), Sugar Plum Fairy (The Nutcracker), Princess Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty), Lise (La Fille mal gardée), Titania (The Dream), Marguerite (Marguerite and Armand), Juliet, Tatiana (Onegin), Manon, Sylvia, Mary Vetsera (Mayerling), Natalia Petrovna (A Month in the Country), Anastasia, Gamzatti and Nikiya (La Bayadère) and roles in Rhapsody, Serenade, Raymonda Act III, DGV: Danse à grande vitesse and Tchaikovsky Pas de deux. -

Premieres on the Cover People

PDL_REGISTRATION_210x297_2017_Mise en page 1 01.06.17 10:52 Page1 Premieres 18 Bertaud, Valastro, Bouché, BE PART OF Paul FRANÇOIS FARGUE weighs up four new THIS UNIQUE ballets by four Paris Opera dancers EXPERIENCE! 22 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas MIKE DIXON considers Daniel de Andrade's take on John Boyne's wartime novel 34 Swan Lake DEBORAH WEISS on Krzysztof Pastor's new production that marries a slice of history with Reece Clarke. Photo: Emma Kauldhar the traditional story P RIX 38 Ballet of Difference On the Cover ALISON KENT appraises Richard Siegal's new 56 venture and catches other highlights at Dance INTERNATIONAL BALLET COMPETITION 2017 in Munich 10 Ashton JAN. 28 TH – FEB. 4TH, 2018 AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal DE Ballet's last programme in London this Whipped Cream 42 season AMANDA JENNINGS savours the New York premiere of ABT's sweet confection People L A U S ANNE 58 Dangerous Liaisons ROBERT PENMAN reviews Cathy Marston's 16 Zenaida's Farewell new ballet in Copenhagen MIKE DIXON catches the live relay from the Royal Opera House 66 Odessa/The Decalogue TRINA MANNINO considers world premieres 28 Reece Clarke by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck EMMA KAULDHAR meets up with The Royal Ballet’s Scottish first artist dancing 70 Preljocaj & Pite principal roles MIKE DIXON appraises Scottish Ballet's bill at Sadler's Wells 49 Bethany Kingsley-Garner GERARD DAVIS catches up with the Consort and Dream in Oakland 84 Scottish Ballet principal dancer CARLA ESCODA catches a world premiere and Graham Lustig’s take on the Bard’s play 69 Obituary Sergei Vikharev remembered 6 ENTRE NOUS Passing on the Flame: 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 78 Luca Masala 101 WHAT’S ON AMANDA JENNINGS meets the REGISTRATION DEADLINE contents 106 PEOPLE PAGE director of Academie de Danse Princesse Grace in Monaco Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle in Ashton's Marguerite and Armand. -

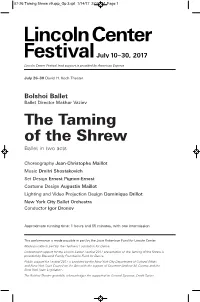

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4

07-26 Taming Shrew v9.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 26–30 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev The Taming of the Shrew Ballet in two acts Choreography Jean-Christophe Maillot Music Dmitri Shostakovich Set Design Ernest Pignon-Ernest Costume Design Augustin Maillot Lighting and Video Projection Design Dominique Drillot New York City Ballet Orchestra Conductor Igor Dronov Approximate running time: 1 hours and 55 minutes, with one intermission This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of The Taming of the Shrew is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. 07-26 Taming Shrew.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/18/17 12:10 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Wednesday, July 26, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. The Taming of the Shrew Katharina: Ekaterina Krysanova Petruchio: Vladislav Lantratov Bianca: Olga Smirnova Lucentio: Semyon Chudin Hortensio: Igor Tsvirko Gremio: Vyacheslav Lopatin The Widow: Yulia Grebenshchikova Baptista: Artemy Belyakov The Housekeeper: Yanina Parienko Grumio: Georgy Gusev MAIDSERVANTS Ana Turazashvili, Daria Bochkova, Anastasia Gubanova, Victoria Litvinova, Angelina Karpova, Daria Khokhlova SERVANTS Alexei Matrakhov, Dmitry Dorokhov, Batyr Annadurdyev, Dmitri Zhuk, Maxim Surov, Anton Savichev There will be one intermission. -

St. Petersburg Is Recognized As One of the Most Beautiful Cities in the World. This City of a Unique Fate Attracts Lots of Touri

I love you, Peter’s great creation, St. Petersburg is recognized as one of the most I love your view of stern and grace, beautiful cities in the world. This city of a unique fate The Neva wave’s regal procession, The grayish granite – her bank’s dress, attracts lots of tourists every year. Founded in 1703 The airy iron-casting fences, by Peter the Great, St. Petersburg is today the cultural The gentle transparent twilight, capital of Russia and the second largest metropolis The moonless gleam of your of Russia. The architectural look of the city was nights restless, When I so easy read and write created while Petersburg was the capital of the Without a lamp in my room lone, Russian Empire. The greatest architects of their time And seen is each huge buildings’ stone worked at creating palaces and parks, cathedrals and Of the left streets, and is so bright The Admiralty spire’s flight… squares: Domenico Trezzini, Jean-Baptiste Le Blond, Georg Mattarnovi among many others. A. S. Pushkin, First named Saint Petersburg in honor of the a fragment from the poem Apostle Peter, the city on the Neva changed its name “The Bronze Horseman” three times in the XX century. During World War I, the city was renamed Petrograd, and after the death of the leader of the world revolution in 1924, Petrograd became Leningrad. The first mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, returned the city its historical name in 1991. It has been said that it is impossible to get acquainted with all the beauties of St. -

The History of Russian Ballet

Pet’ko Ludmyla, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Savina Kateryna Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Institute of Arts, student THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN BALLET Петько Людмила к.пед.н., доцент НПУ имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев) Савина Екатерина Национальный педагогический университет имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев), Інститут искусствб студентка Annotation This article is devoted to describing of history of Russian ballet. The aim of the article is to provide the reader some materials on developing of ballet in Russia, its influence on the development of ballet schools in the world and its leading role in the world ballet art. The authors characterize the main periods of history of Russian ballet and its famous representatives. Key words: Russian ballet, choreographers, dancers, classical ballet, ballet techniques. 1. Introduction. Russian ballet is a form of ballet characteristic of or originating from Russia. In the early 19th century, the theatres were opened up to anyone who could afford a ticket. There was a seating section called a rayok, or «paradise gallery», which consisted of simple wooden benches. This allowed non- wealthy people access to the ballet, because tickets in this section were inexpensive. It is considered one of the most rigorous dance schools and it came to Russia from France. The specific cultural traits of this country allowed to this technique to evolve very fast reach his most perfect state of beauty and performing [4; 22]. II. The aim of work is to investigate theoretical material and to study ballet works on this theme. To achieve the aim we have defined such tasks: 1. -

Kirov Ballet & Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre

Cal Performances Presents Tuesday, October 14–Sunday, October 19, 2008 Zellerbach Hall Kirov Ballet & Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre (St. Petersburg, Russia) Valery Gergiev, Artistic & General Director The Company Diana Vishneva, Irma Nioradze, Viktoria Tereshkina Alina Somova, Yulia Kasenkova, Tatiana Tkachenko Andrian Fadeev, Leonid Sarafanov, Yevgeny Ivanchenko, Anton Korsakov Elena Bazhenova, Olga Akmatova, Daria Vasnetsova, Evgenia Berdichevskaya, Vera Garbuz, Tatiana Gorunova, Grigorieva Daria, Natalia Dzevulskaya, Nadezhda Demakova, Evgenia Emelianova, Darina Zarubskaya, Lidia Karpukhina, Anastassia Kiru, Maria Lebedeva, Valeria Martynyuk, Mariana Pavlova, Daria Pavlova, Irina Prokofieva, Oksana Skoryk, Yulia Smirnova, Diana Smirnova, Yana Selina, Alisa Sokolova, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Lira Khuslamova, Elena Chmil, Maria Chugay, Elizaveta Cheprasova, Maria Shirinkina, Elena Yushkovskaya Vladimir Ponomarev, Mikhail Berdichevsky, Stanislav Burov, Andrey Ermakov, Boris Zhurilov, Konstantin Zverev, Karen Ioanessian, Alexander Klimov, Sergey Kononenko, Valery Konkov, Soslan Kulaev, Maxim Lynda, Anatoly Marchenko, Nikolay Naumov, Alexander Neff, Sergey Popov, Dmitry Pykhachev, Sergey Salikov, Egor Safin, Andrey Solovyov, Philip Stepin, Denis Firsov, Maxim Khrebtov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vasily Sherbakov, Alexey Timofeev, Kamil Yangurazov Kirov Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre U.S. Management: Ardani Artists Management, Inc. Sergei Danilian, President & CEO Made possible, in part, by The Bernard Osher Foundation, in honor of Robert -

World Ballet Day 2014

GLOBAL FIRST: FIVE WORLD-CLASS BALLET COMPANIES, ONE DAY OF LIVE STREAMING ON WEDNESDAY 1 OCTOBER www.roh.org.uk/worldballetday The A u str a lia n B a llet | B o lsho i B a llet | The R o y a l B a llet | The N a tio n a l B a llet o f C a n a d a | S a n F r a n c isc o B a llet T h e first ev er W o r ld B a llet D a y w ill see an u n p rec ed en ted c ollab oration b etw een fiv e of th e w orld ‘s lead in g b allet c om p an ies. T h is on lin e ev en t w ill tak e p lac e on W ed n esd ay 1 O c tob er w h en eac h of th e c om p an ies w ill stream liv e b eh in d th e sc en es ac tion from th eir reh earsal stu d ios. S tartin g at th e b egin n in g of th e d an c ers‘ d ay , eac h of th e fiv e b allet c om p an ies œ The A u str a lia n B a llet, B o lsho i B a llet, The R o y a l B a llet, The N a tio n a l B a llet o f C a n a d a an d S a n F r a n c isc o B a llet œ w ill tak e th e lead for a fou r h ou r p eriod stream in g liv e from th eir h ead q u arters startin g w ith th e A u stralian B allet in M elb ou rn e.