Access Article In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Complete Course

A Complete Course Forum Theological Midwest Author: Rev.© Peter V. Armenio Publisher:www.theologicalforum.org Rev. James Socias Copyright MIDWEST THEOLOGICAL FORUM Downers Grove, Illinois iii CONTENTS xiv Abbreviations Used for 43 Sidebar: The Sanhedrin the Books of the Bible 44 St. Paul xiv Abbreviations Used for 44 The Conversion of St. Paul Documents of the Magisterium 46 An Interlude—the Conversion of Cornelius and the Commencement of the Mission xv Foreword by Francis Cardinal George, to the Gentiles Archbishop of Chicago 47 St. Paul, “Apostle of the Gentiles” xvi Introduction 48 Sidebar and Maps: The Travels of St. Paul 50 The Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 49– 50) 1 Background to Church History: 51 Missionary Activities of the Apostles The Roman World 54 Sidebar: Magicians and Imposter Apostles 3 Part I: The Hellenistic Worldview 54 Conclusion 4 Map: Alexander’s Empire 55 Study Guide 5 Part II: The Romans 6 Map: The Roman Empire 59 Chapter 2: The Early Christians 8 Roman Expansion and the Rise of the Empire 62 Part I: Beliefs and Practices: The Spiritual 9 Sidebar: Spartacus, Leader of a Slave Revolt Life of the Early Christians 10 The Roman Empire: The Reign of Augustus 63 Baptism 11 Sidebar: All Roads Lead to Rome 65 Agape and the Eucharist 12 Cultural Impact of the Romans 66 Churches 13 Religion in the Roman Republic and 67 Sidebar: The Catacombs Roman Empire 68 Maps: The Early Growth of Christianity 14 Foreign Cults 70 Holy Days 15 Stoicism 70 Sidebar: Christian Symbols 15 Economic and Social Stratification of 71 The Papacy Roman -

Special Report on Religious Life

Catholic News Agency and women who Year-long MAJOR ORDERS TYPES OF RELIGIOUS ORDERS dedicate their lives celebrations AND THEIR CHARISMS to prayer, service The Roman Catholic Church recognizes different types of religious orders: and devotion. Year of Marriage, A religious order or congregation is Many also live as Nov. 2014- distinguished by a charism, or particular • Monastic: Monks or nuns live and work in a monastery; the largest monastic order, part of a commu- Dec. 2015 grace granted by God to the institute’s which dates back to the 6th century, is the Benedictines. nity that follows a founder or the institute itself. Here • Mendicant: Friars or nuns who live from alms and actively participate in apostolic work; specific religious Year of Faith, are just a few religious orders and the Dominicans and Franciscans are two of the most well-known mendicant orders. rule. They can Year of Prayer, congregations with their charisms: • Canons Regular: Priests living in a community and active in a particular parish. include both Oct. 2012- • Clerks Regular: Priests who are also religious men with vows and who actively clergy and laity. Nov. 2013 Order/ participate in apostolic work. Most make public Congregation: Charism: vows of poverty, Year for Priests, obedience and June 2009- Dominicans Preaching and chastity. Priests June 2010 teaching who are religious Benedictines Liturgical are different from Year of St. Paul, prayer and diocesan priests, June 2008- monasticism who do not take June 2009 Missionaries Serving God vows. of Charity among the Religious congregations differ from reli- “poorest of the gious orders mainly in terms of the vows poor” that are taken. -

The Dialogue Between Religion and Science in Today's World from The

International Journal of Orthodox Theology 8:3 (2017) 203 urn:nbn:de:0276-2017-3075 Gavril Trifa The Dialogue between Religion and Science in Today’s World from the View of Orthodox Spirituality Abstract One of the core issues of today’s world, the dialogue between science and religion has recently come to the attention of new fields of knowledge, which points to a change in some of the “classical” elements. Having a different history in the East and the West, in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, the relation between faith and science has lived through some problematic centuries, marked by the attempt of some scientific domains to prove the universe’s materialist ontology and thus the uselessness of religion. This paper aims to present an overview of the Rev. Assist. Prof. Ph.D. stages that marked the often radical Gavril Trifa, Faculty of separation of science from religion, by Orthodox Theology of the highlighting the mutations recorded West University of Timi- during the past few decades not only şoara, Romania 204 Gavril Trifa in society but also in the lives of the young, as a result of the unprecedented development of technology. With technology failing to raise both communication and interpersonal communication to the anticipated level, recent research does not hesitate in emphasizing the unfavourable consequences bring about by the development of the means of communication, regarding the human being’s relation to oneself and one’s neighbours. The solutions we have identified enable an update of the patristic model concerning the relation between religion and science, in the spirit of humility, the one that can bring the Light of life. -

Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R

Marian Studies Volume 36 Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth National Convention of The Mariological Society of America Article 11 held in Dayton, Ohio 1985 Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R. Vasey Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vasey, Vincent R. (1985) "Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ," Marian Studies: Vol. 36, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol36/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vasey: Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle MARY IN THE DOCTRINE OF BERULLE ON THE MYSTERIES OF CHRIST Two monuments Berulle left the Church, aere perennina: more enduring than bronze, are his writings and his Congrega tion of the Oratory. He took part in the great controversies of his time, religious and political, but his figure takes its greatest lus ter with the passing of years because of his spiritual work and the influence he exerts in the Church by those endued with his teaching. From his integrated life originated both his works and his institution; that is why both his writings and the Oratory are intimately connected. His writings in their final synthesis-and we are concerned above all with the culmination of his contem plation and study-center about Christ, and his restoration of the priesthood centers about Christ. -

Mendicant Orders of the Middle Ages

Mendicant Orders of the Middle Ages The Monks and Monasteries of the early Middle Ages played a critical roal in the preservation and promotion of Christian culture. The accomplishments of the monks, especially during the 'Dark Ages', are too numerous to list. They were the both missionaries and custodians of Catholic culture for generations, and the monastic reforms of the tenth century paved the way for the reforms of the secular clergy that followed. By the beginning of the 13th century, however, there was seen a need for a new type of religious community, and thus were born the Mendicant Orders. The word 'Mendicant' means beggar, and this was due to the fact that the Mendicant Friars, in contrast to the Benedictine Monks, lived primarily in towns, rather than on propertied estates. Since they did not own property, they were not beholden to secular rulers and were free to serve the poor, preach the gospel, and uphold Christian ideals without compromise. The Investiture Controversy of the previous century, and the underlying problems of having prelates appointed by and loyal to local princes, was one of the reasons for the formation of mendicant orders. Even though monks took a vow of personal poverty, they were frequently members of wealthy monasteries, which were alway prone to corruption and politics. The mendicant commitment to poverty, therefore, prohibited the holding of income producing property by the orders, as well as individuals. The poverty of the mendicant orders gave them great freedom, in the selection of their leaders, in the their mobility, and in their active pursuits. -

The Mendicant Preachers and the Merchant's Soul

MARK HANSSEN THE MENDICANT PREACHERS AND THE MERCHANT'S SOUL THE CIVILIZATION OF COMMERCE IN THE LATE- MIDDLE AGES AND RENAISSANCE ITALY (1275-1425) Tesis doctoral dirigida por PROF. DR. MIGUEL ALFONSO MARTÍNEZ-ECHEVARRÍA Y ORTEGA PROF. DR. ANTONIO MORENO ALMÁRCEGUI FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES PAMPLONA, 2014 Table of contents Prologue .......................................................................................................... 7 PART I: BACKGROUND Chapter 1: Introduction The Merchant in the Wilderness ............................. 27 1. Economic Autarky and Carolingian Political "Augustinianism" ........................ 27 2. The Commercial Revolution ................................................................................ 39 3. Eschatology and Civilization ............................................................................... 54 4. Plan of the Work .................................................................................................. 66 Chapter 2: Theology and Civilization ........................................................... 73 1. Theology and Humanism ..................................................................................... 73 2. Christianity and Classical Culture ...................................................................... 83 3. Justice, Commerce and Political Society............................................................. 95 PART II: SCHOLASTIC PHILOSOPHICAL-THEOLOGY, ETHICS AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Introduction................................................................................................ -

UNIFICATION and CONFLICT the Church Politics Of

STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXVI UNIFICATION AND CONFLICT The Church Politics of Alonso de Montúfar OP, Archbishop of Mexico, 1554-1572. Magnus Lundberg COPYRIGHT © Magnus Lundberg 2002 Lund University Department of Theology and Religious Studies Allhelgona kyrkogata 8, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden PRINTED IN SWEDEN BY KFS i Lund AB, Lund 2002 ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 91-85424-69-2 PUBLISHED AND DISTRIBUTED BY Swedish Institute of Missionary Research P.O. Box 1526 SE-751 45 Uppsala, Sweden 2 Alonso de Montúfar OP The Metropolitan Cathedral, Mexico City. Photo: Magnus Lundberg. 3 Alonso de Montúfar OP Santa Cruz la Real, Granada. Photo: Roberto Travesí. (Huerga 1995:81). 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of a doctoral dissertation implies many hours of solitary work. This is not least the case if you spend most of your days in the company of a man who died over four hundred years ago, as I have done in the last couple of years. Therefore, I here want to take the opportunity to acknowledge some of the many people who have made my work less lonely and who have helped me in various ways. My first sincere words of acknowledgement are due to my supervisor Dr. Aasulv Lande, Professor of Missiology with Ecumenical Theology at Lund University, who has been an unfailing source of encouragement during my years of undergraduate and graduate studies. In particular I want to thank him for believing in my dissertation project even in the dark periods when I did not do so myself. Likewise, I am especially indebted to Professor emeritus Magnus Mörner, who kindly accepted to become my assistant supervisor. -

Reading Records of Literary Authors: a Comoatisom.Of Some Publishedfaotebocks

DOCUMENT INSURE j ED41.820. CS 204 003 0 AUTHOR Murray, Robin Mark '. TITLE. Reading Records of Literary Authors: A ComOatisom.of Some Publishedfaotebocks. PUB DATE Dec 77 NOTE 118p.; N.A. thesis, The Ilniversity.of Chicago . I EDRS PRICE f'"' NF-S0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; Bibliographies;_ Rooks; ,ocompcsiticia (Literary); *Creative Writing; *Diariei; Literature* Masters Theses; *Poets; Reading Habits; Reading Materials; *Recrtational Reading; Study Habits IDENTIFIERS Notebooks;.*Note Taking - ABSTRACT The significance ofauthore reading notes may lie not only in their mechanical function as inforna'tion storage devices providing raw materials for writing, but also in their ability to 'concentrate and to mobilize the latent ,emotional and. creative 1 resources of their keepers. This docmlent examines records of 'reading found in the published notebcols'of eight najcr_British.and United States writers of the sixteenth through twentieth. centuries. Through eonparison of their note-taking practices, the following topics are explored: how each author came to make reading notes, the,form.in which notes were' made, and the vriteiso habits of consulting; and using their notes (with special reference to distinctly literary uses). The eight writers whose notebooks ares-exaninea in dtpth are Francis Badonc John Milton, Samuel Coleridge,.Ralph V. Emerson, Henry D. Thoreau, Mark Twain, Thomas 8ardy, and Thomas Violfe.:The trends that emerge from these eight case studiesare discussed, and an extensive bibliograity of published -

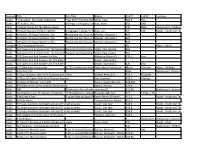

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

What's New About the New Evangelization?

SILVER LAKE COLLEGE OF THE HOLY FAMILY What’s New About the New Evangelization? Learning from our heritage Sister Marie Kolbe Zamora, S.T.L. Contents What’s New About the New Evangelization? Learning from our heritage. .................................................. 3 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Purpose of this Presentation ........................................................................................................................ 3 Outline of this Presentation .......................................................................................................................... 4 What IS the New Evangelization? ................................................................................................................. 4 Overcoming Obstacles .............................................................................................................................. 5 Defining Evangelization ............................................................................................................................. 5 First Wave of Evangelization - Evangelizing Greco-Roman World ................................................................ 6 Era Context / Recipients............................................................................................................................ 6 First Wave of Evangelization Details: ....................................................................................................... -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: an Overview of Recent Literature

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: An Overview of Recent Literature Caroline Bruzelius European cities of any size had one or more mendicant convents. These institutions re- shaped the topographical, social, and economic realities of urban life in the late Middle Ages; they also often de-stabilized traditional parochial organization and created new poles of influence and activity within cities. Mendicants expanded and “anchored” new suburbs, but they sometimes also settled in the heart of a city, destroying neighborhoods in the process. As the thirteenth century progressed, friars increasingly inserted large conventual complexes within densely inhabited urban space. In Italy in particular they also carved out open areas (piazzas) for preaching. Yet, although it is hard to imagine any medieval city without its mendicant convents, the reconstruction of their presence as a physical, spiritual, economic, and social phenomenon after the systematic and thorough destruction that began as early as the sixteenth-century Reformation remains a challenging task. This essay is an overview of the main themes in recent literature on mendicant build- ings in the Middle Ages 1. A number of books on the architecture of the friars have appeared in the past twenty years. These are dominated by three broad types of analysis. The first focuses on an individual site, either a church alone or a convent as a whole (a few examples are GAI, 1994; BARCLAY LLOYD, 2004; CERVINI, DE MARCHI, 2010; DE MARCHI, PIRAZ, 2011). The second category consists of the survey that covers a region and/or an extended chrono- logical period (DELLWING, 1970, 1990; SCHENKLUHN, 2000, 2003; COOMANS, 2001; VOLTI, 2003; TODENHÖFER, 2010).