Critical Multicultural Analysis of Reconstructed Folk Tales : Rumpelstiltskin Is My Name, Power Is My Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

The Caldecott Medal 2021

Caldecott Medal Books oppl.org/kids-lists The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children. It is given to the illustrator of the most distinguished American picture book published the preceding year. The name of Randolph Caldecott, an English illustrator of books for children, was chosen for the medal because his work best represented the “joyousness of picture books as well as their beauty.” The horseman on the medal is taken from one of Caldecott’s illustrations for “The Diverting History of John Gilpin” (1878). The medal was originally donated by publisher Frederic G. Melcher (1879–1963), and is now donated by his son, Daniel. 1939 Mei Li Handforth 1972 One Fine Day Hogrogian 1940 Abraham Lincoln d’Aulaire 1973 The Funny Little Woman Lent 1941 They Were Strong and Good Lawson 1974 Duffy and the Devil Zemach 1942 Make Way for Ducklings McCloskey 1975 Arrow to the Sun McDermott 1943 The Little House Burton 1976 Why Mosquitoes Buzz in 1944 Many Moons Slobodkin People’s Ears Dillon 1945 Prayer for a Child Jones 1977 Ashanti to Zulu: 1946 The Rooster Crows Petersham African Traditions Dillon 1947 The Little Island Weisgard 1978 Noah’s Ark Spier 1948 White Snow, Bright Snow Duvoisin 1979 Girl Who Loved Wild Horses Goble 1949 The Big Snow Hader 1980 Ox-Cart Man Cooney 1950 Song of the Swallows Politi 1981 Fables Lobel 1951 The Egg Tree Milhous 1982 Jumanji Van Allsburg 1952 Finders Keepers Mordvinoff 1983 Shadow Brown 1953 The Biggest Bear Ward 1984 The Glorious Flight Provensen 1954 Madeline’s Rescue -

Caldecott Medal Winners

C A L D E C O T T 1951 The Egg Tree by Katherine Milhous 1943 The Little House by Virginia Lee Burton M EDAL 1942 Make Way for Ducklings by Robert INNERS 1950 Song of the Swallows by Leo Politi W McCloskey 1949 The Big Snow by Berta and Elmer Hader 1941 They Were Strong and Good by Robert Law- son The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the Association of Library Service to Children, a divi- 1948 White Snow, Bright Snow by Alvin Tres- 1940 Abraham Lincoln by Ingri Parin D’Aulaire sion of the American Library Association, to the illustrator of the most distinguished American pic- selt, ill by Roger Duvoisin 1939 Mei Li by Thomas Handforth ture book for children. The medal honors Randolph Caldecott, a famous English illustrator of children’s 1938 Animals of the Bible by Helen D. Fish, 1947 The Little Island by Golden MacDonald ill by Dorothy Lathrop 2011 A Sick Day for Amos McGee ill Erin Stead Ill by Leonard Weisgard 2010 The Lion and the Mouse by Jerry Pinkney 2009 The House in the Night by Susan Swanson 1946 Rooster Crows by Maud and Miska Peter- 2008 The Invention of Hugo Cabaret by Brian Sel- znik sham 2007 Flotsam by David Wiesner 2006 The Hello, Goodbye Window by Chris Raschka 2005 Kitten’s First Full Moon by Kevin Henkes 1945 Prayer for a Child by Rachel Field, 2004 The Man Who Walked between Two Towers by Mordicai Gerstein Ill by Elizabeth Orton Jones 2003 My Friend Rabbit by Eric Rohmann 2002 The Three Pigs by David Wiesner 2001 So You Want to Be President by Judith 1944 Many Moons by James Thruber, Ill by St.George 2000 Joseph Had A little Overcoat by Simms Tabak Louis Slobodkin 1999 Snowflake Bentley by Jacqueline Briggs Mar- tin 1998 Rapunzel by Paul O. -

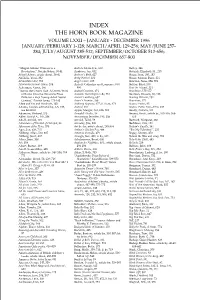

Index the Horn Book Magazine

INDEX THE HORN BOOK MAGAZINE VOLUME LXXII – JANUARY - DECEMBER 1996 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1-128; MARCH/APRIL 129-256; MAY/JUNE 257- 384; JULY/AUGUST 385-512; SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 513-656; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 657-800 “Abigail Adams: Witness to a Andrew McAndrew, 690 Batboy, 346 Revolution,” Natalie Bober, 38-41 Andrews, Jan, 632 Battrick, Elizabeth M., 239 Abigail Adams, article about, 38-41 Andrew’s Bath, 627 Bauer, Joan, 180, 183 Abolafia, Yossi, 332 Andy Warhol, 301 Bauer, Marion Dane, 221 Abracadabra Kid, 758 Angel’s Gate, 205 Bawden, Nina, 354; 591 Absolutely Normal Chaos, 204 Anholt, Catherine and Laurence, 689, Baylor, Byrd, 100 Ackerman, Karen, 186 690 Bear for Miguel, 331 “Across the Center Line: A Dozen Years Animal Crackers, 474 Beardance, 175-177 of Books from the Delacorte Press Animals That Ought to Be, 754 Bearden, Romare, 86; 185 Prize for a First Young-Adult Novel Anisett Lundberg, 637 Bearing Witness, 232 Contest,” Patrick Jones, 178-183 Annie’s Promise, 486 Bearstone, 175 Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, 102 Anthony Reynoso, 477; il. from, 478 Beatrix Potter, 95 Adams, Lauren, editorial by, 4-5; 133; Antics!, 484 Beatrix Potter 1866–1943, 239 see Booklist Apple, Margot, 484; 626; 765 Beatty, Patricia, 101 Adamson, Richard, 573 Armadillo Rodeo, 59 Beavin, Kristi, article by, 105-109; 566- Adler, David A., 187, 236 Armstrong, Jennifer, 193, 236 573 Adoff, Arnold, 103 Arnold, Tedd, 59 Bechard, Margaret, 360 Adventures of Hershel of Ostropol, 83 Arnosky, Jim, 220 Beddows, Eric, 721 Afternoon of the Elves, 573 Art books, article about, 295-304 Beduin’s Gazelle, 341 Agee, Jon, 626; 715 Arthur’s Chicken Pox, 484 “Bee My Valentine!”, 235 Ahlberg, Allan, 590; 687 Artist in Overalls, 479 Begay, Shonto, 470 Ahlberg, Janet, 687 Aruego, Jose, 458; il. -

The Books That Are Caldecott Honors Winners Will Be Marked with a Spine Label

2013 “THIS IS NOT MY HAT” EASY K 2014 “LOCOMOTIVE” J 385.097 FLOCA 2015 “ADVENTURES OF BEEKLE” EASY S 2016 “FINDING WINNIE: THE TRUE STORY OF THE WORL’DS MOST FAMOUS BEAR” The books that are Caldecott medal winners will be marked with a spine label. The books that are Caldecott Honors winners will be marked with a spine label. Kingsport Public Library 400 Broad Street Kingsport, TN 37660 www.kingsportlibrary.org (423) 229-9366 Updated 4/22/2015 The Caldecott Medal was named in honor of nineteenth-century English 1962 “ONCE A MOUSE” EASY B 1990 “LON PO PO: A RED-RIDING illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is 1963 “THE SNOWY DAY” EASY K HOOD STORY FROM CHINA” awarded annually by the Association 1964 “WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE” EASY S J 398.2 Young for Library Service to Children, a 1991 “BLACK AND WHITE” EASY M division of the American Library 1965 “MAY I BRING A FRIEND” EASY D Association, to the artist of the most 1966 “ALWAYS ROOM FOR ONE MORE” 1992 “TUESDAY” EASY W distinguished American picture book EASY L 1993 “MIRETTE ON THE HIGH WIRE” for children. 1967 “SAM, BANGS & MOONSHINE” EASY M 1938 “ANIMALS OF THE BIBLE” 1968 “DRUMMER HOFF” EASY E 1994 “GRANDFATHER’S JOURNEY” J 220.8 Lathrop 1969 “THE FOOL OF THE WORLD & THE EASY S 1939 “MEI LI” Easy H FLYING SHIP” 1995 “SMOKY NIGHT” 1940 “ARAHAM LINCOLN” JB Lincoln 1970 “SYLVESTER AND THE MAGIC PEBBLE” 1996 “OFFICER BUCKLE AND 1941 “THEY WERE STRONG AND EASY A GLORIA” EASY R GOOD” J 920 LAWSON 1971 “A STORY-A STORY: AN AFRICAN TALE” 1997 “GOLEM” EASY W 1942 “MAKE WAY FOR DUCKLINGS” J 398.2 Haley EASY M 1972 “ONE FINE DAY” EASY H 1998 “RAPUNZEL” EASY Z 1943 “THE LITTLE HOUSE” 1973 “THE FUNNY LITTLE WOMAN” EASY M 1999 “SNOWFLAKE BENTLEY” 1944 “MANY MOONS” EASY T 1974 “DUFFY AND THE DEVIL” J 551.5784 MARTIN 1945 “PRAYER FOR A CHILD” 1975 “ARROW TO THE SUN” 2000 “JOSEPH HAD A LITTLE J 242.62 Field OVERCOAT” EASY T 1976 “WHY MOSQUITOES BUZZ IN PEOPLE’S 1946 “THE ROOSTER CROWS” EASY P 2001 “SO YOU WANT TO BE PRESI- EARS” EASY A DENT” J 973.099 St. -

Grimm's Fairy Stories

Grimm's Fairy Stories Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm The Project Gutenberg eBook, Grimm's Fairy Stories, by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Illustrated by John B Gruelle and R. Emmett Owen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Grimm's Fairy Stories Author: Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm Release Date: February 10, 2004 [eBook #11027] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES*** E-text prepared by Internet Archive, University of Florida, Children, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 11027-h.htm or 11027-h.zip: (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h/11027-h.htm) or (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h.zip) GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES Colored Illustrations by JOHN B. GRUELLE Pen and Ink Sketches by R. EMMETT OWEN 1922 CONTENTS THE GOOSE-GIRL THE LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER HANSEL AND GRETHEL OH, IF I COULD BUT SHIVER! DUMMLING AND THE THREE FEATHERS LITTLE SNOW-WHITE CATHERINE AND FREDERICK THE VALIANT LITTLE TAILOR LITTLE RED-CAP THE GOLDEN GOOSE BEARSKIN CINDERELLA FAITHFUL JOHN THE WATER OF LIFE THUMBLING BRIAR ROSE THE SIX SWANS RAPUNZEL MOTHER HOLLE THE FROG PRINCE THE TRAVELS OF TOM THUMB SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THE THREE LITTLE MEN IN THE WOOD RUMPELSTILTSKIN LITTLE ONE-EYE, TWO-EYES AND THREE-EYES [Illustration: Grimm's Fairy Stories] THE GOOSE-GIRL An old queen, whose husband had been dead some years, had a beautiful daughter. -

An Analysis of the Devil in the Original Folk and Fairy Tales

Syncretism or Superimposition: An Analysis of the Devil in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm Tiffany Stachnik Honors 498: Directed Study, Grimm’s Fairy Tales April 8, 2018 1 Abstract Since their first full publication in 1815, the folk and fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm have provided a means of studying the rich oral traditions of Germany. The Grimm brothers indicated time and time again in their personal notes that the oral traditions found in their folk and fairy tales included symbols, characters, and themes belonging to pre-Christian Germanic culture, as well as to the firmly Christian German states from which they collected their folk and fairy tales. The blending of pre-Christian Germanic culture with Christian, German traditions is particularly salient in the figure of the devil, despite the fact that the devil is arguably one of the most popular Christian figures to date. Through an exploration of the phylogenetic analyses of the Grimm’s tales featuring the devil, connections between the devil in the Grimm’s tales and other German or Germanic tales, and Christian and Germanic symbolism, this study demonstrates that the devil in the Grimm’s tales is an embodiment of syncretism between Christian and pre-Christian traditions. This syncretic devil is not only consistent with the history of religious transformation in Germany, which involved the slow blending of elements of Germanic paganism and Christianity, but also points to a greater theme of syncretism between the cultural traditions of Germany and other -

PBS Lesson Series

PBS Lesson Series ELA: Grade 2, Lesson 6, Rumpelstiltskin Lesson Focus: Students will build knowledge about fairy tales. Practice Focus: Sequencing story events in notes and rewriting for a retelling of Rumpelstiltskin Objective: Students will use Rumpelstiltskin to take notes on a graphic organizer with a focus on summarizing the fairy tale. Academic Vocabulary: royal, royalty, straw TN Standards: 2.RL.KID.2, 2.RL.KID.3, 2.FL.PWR.3 Teacher Materials: The teacher packet for ELA, Grade 2, Lesson 6 Chart paper – one page is prepared with the word “Rumpelstiltskin” written and divided into syllables Markers Two pieces of paper to model with Student Materials: Two pieces of paper and a pencil, and a surface to write on Crayons, markers, or colored pencils The student packet for ELA, Grade 2, Lesson 6 which can be found at www.tn.gov/education Teacher Do Students Do Opening (1 min) Students gather materials for the Hello! Welcome to Tennessee’s At Home Learning Series for lesson and prepare to engage with literacy! Today’s lesson is for all our 2nd graders out there, the lesson’s content. though everyone is welcome to tune in. This lesson is the first in this week’s series. My name is ____ and I’m a ____ grade teacher in Tennessee schools. I’m so excited to be your teacher for this lesson! Welcome to my virtual classroom! If you didn’t see our previous lesson, you can find it on www.tn.gov/education. You can still tune in to today’s lesson if you haven’t seen any of our others. -

Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme

Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 6 Article 4 1-1-1998 Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme Kimberly J. Pierson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierson, Kimberly J. (1998) "Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme," Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIRCLES 1998 Vol. VI REVENGE AND PUNISHMENT: LEGAL PROTOTYPE AND FAIRY TALE THEME By Kimberly J. Pierson' The study of the interrelationship between law and literature is currently very much in vogue, yet many aspects of it are still relatively unexamined. While a few select works are discussed time and time again, general children's literature, a formative part of a child's emerging notion of justice, has been only rarely considered, and the traditional fairy tale2 sadly ignored. This lack of attention to the first examples of literature to which most people are exposed has had a limiting effect on the development of a cohesive study of law and literature, for, as Ian Ward states: It is its inter-disciplinary nature which makes children's literature a particularly appropriate subject for law and literature study, and it is the affective importance of children's literature which surely elevates the subject fiom the desirable to the necessary. -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

Caldecott Medal Winners

Hey, Al by Arthur Yorinks (1987) Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears by Caldecott Location: Picture Book Yorinks Verna Aardema (1976) Location: Picture Book Tales Why The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg Medal (1986) Arrow to the Sun by Gerald McDermott Location: Kids Holiday Christmas Van Allsburg (1975) Location: Picture Book Tales Arrow Winners Saint George and the Dragon by Marga- ret Hodges (1985) Duffy and the Devil by Harve Zemach Location: Kids 398.2342 Hodges (1974) The Randolph Caldecott Medal is awarded Location: Picture Book Tales Duffy Shadow by Blaise Cendrars annually by the Association for Library Service (1983) The Funny Little Woman by Arlene Mosel to Children to “the artist of the most distin- Location: Picture Book Tales (1973) guished American picture book for children.” Shadow Location: Picture Book Tales Funny One Fine Day by Nonny Hogrogian (1972) Jumanji by Chris Van Allsburg (1982) Location: Picture Book Hogrogian Location: Kids Illustrated Fiction Van Allsburg A Story A Story: An African Tale by Gail E. Fables by Arnold Lobel (1981) Haley (1971) Location: Picture Book Tales Collection Location: Picture Book Tales Story Ox-Cart Man by Donald Hall (1980) Sylvester and the Magic Pebble Location: Picture Book Hall by William Steig (1970) Location: Picture Book Steig The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses by Paul Goble (1979) Location: Picture Book Tales Girl Noah's Ark by Peter Spier (1978) Wilmington Memorial Library Location: Picture Book Spier 175 Middlesex Ave Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions by Wilmington, MA 01887 Margaret Musgrove (1977) wilmlibrary.org/kids Location: Kids 960 Musgrove Youth Services: 978-694-2098 Wolf in the Snow by Matthew The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Rapunzel by Paul O.