An Analysis of the Devil in the Original Folk and Fairy Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Forest Trees of NC

FFOORREESSTT TTRREEEESS OF NORTH CAROLINA North Carolina Forest Service TWENTIETH EDITION 2012 North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services The North Carolina Forest Service is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. Its programs, activities and employment practices are available to all people regardless of race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, handicap or political affiliation. COMMON FOREST TREES OF NORTH CAROLINA ( R E V I S E D ) A POCKET MANUAL Produced by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consum er Services North Carolina Forest Service Wib L. Owen, State Forester TWENTIETH EDITION 2012 Foreword Trees may be the oldest and largest living things in nature. They are closely associated with our daily lives, yet most of us know little about them and barely can tell one type of tree from another. Sixteen editions of this handy pocket guide have been printed since John Simcox Holmes, North Carolina's first State Forester, put together the first edition in 1922. Holmes' idea was to provide an easy-to-use reference guide to help people of all ages recognize many of our common forest trees on sight. That goal has not changed. Although the book has changed little, some uses of wood and general information about the trees have. Carriages and wagons, for example, aren't often made from Shagbark hickory (or anything else) anymore, and Loblolly pine now is used for making tremendous amounts of pine plywood, something unheard of in the 1920's. Keeping these changes in mind, we revised Common Forest Trees of North Carolina in 1977 and 1995. -

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

People and Trees: Providing Benefits, Overcoming Impediments

63 PEOPLE AND TREES: PROVIDING BENEFITS, OVERCOMING IMPEDIMENTS Dr Jane Tarran Honorary Associate, University of Technology Sydney Former Senior Lecturer and Course Director, BSc (Urban Ecology) Faculty of Science University of Technology Sydney 1.INTRODUCTION The present paper deals with an area that would be familiar to many in the audience on a daily basis, as they manage trees in urban environments with people. Audience members would also be well aware that it is an area fraught with difficulties, as any community includes people with a vast range of attitudes towards trees. Urban tree management involves managing not just the trees, but also the people, particularly their preferences and expectations, regarding the trees in their community. As our knowledge of tree biology continues to improve, and as we understand more and more about what trees require for establishment and continued healthy growth, we are better placed to know what we should be doing to provide what trees need, even if constraints in the trees' environments often make this difficult. The same cannot be said for our knowledge and understanding of people in relation to trees. Whilst there is an increasing body of research on the benefits to people of ‘green environments’, including trees and other plants, there has been little research to date on people's perceptions of, and attitudes towards, trees. Yet people have a profound impact on the existence and survival of urban trees, and whether or not we can achieve worthwhile and sustainable urban forests. Trees and other plants have the potential to make enormous contributions to the economic, environmental and social sustainability of our human settlements. -

Download Season 5 Grimm Free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online

download season 5 grimm free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online. On Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, Nick struggles with how to move forward after the beheading of his mother, the death of Juliette and Adalind being pregnant. Watch Similar Shows FREE Amazon Watch Now iTunes Watch Now Vudu Watch Now YouTube Purchase Watch Now Google Play Watch Now NBC Watch Now Verizon On Demand Watch Now. When you watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 online, the action picks up right where the season finale of Grimm Season 4 left off, with Juliette dead in Nick's arms, Nick's mother's severed head in a box, and Agent Chavez's goons coming to kidnap Trubel. Nick is apparently drugged, and when he awakes, there is no sign that any of this occurred: no body, no box, no head, no Trubel. Was it all a truly horrible dream? Or part of a larger conspiracy? When he tries to tell his friends what happened, they hesitate to believe his claims, especially when he lays the blame at the feet of Agent Chavez. As his mental state deteriorates, will Nick be able to discover the truth about what happened and why? Where is Trubel now, and why did Chavez and her people come to kidnap her? Will his friends ever believe him, or will they continue to doubt his claims about what happened? And what will Nick do now that his and Adalind's baby is on the way? Tune in and watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, "The Grimm Identity," online right here at TV Fanatic to find out what happens. -

1812 GRIMM's FAIRY TALES DEATH's MESSENGERS Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm DEATHS MESSENGERS

1 1812 GRIMM’S FAIRY TALES DEATH’S MESSENGERS Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm Grimm, Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) - German philologists whose collection “Kinder- und Hausmarchen,” known in English as “Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” is a timeless literary masterpiece. The brothers transcribed these tales directly from folk and fairy stories told to them by common villagers. Death’s Messengers (1812) - Death is beaten by a giant then nursed back to life by a kind young man; Death pays the man back by promising to send messengers before coming to end his life. DEATHS MESSENGERS IN ANCIENT TIMES a giant was once traveling on a great highway, when suddenly an unknown man sprang up before him, and said, “Halt, not one step farther!” “What!” cried the giant, “a creature whom I can crush between my fingers, wants to block my way? Who art thou that thou darest to speak so boldly?” “I am Death,” answered the other. “No one resists me, and thou also must obey my commands.” But the giant refused, and began to struggle with Death. It was a long, violent battle. At last the giant got the upper hand, and struck Death down with his fist, so that he dropped by a stone. The giant went his way, and Death lay there conquered, and so weak that he could not get up again. “What will be done now,” said he, “if I stay lying here in a corner? No one will die now in the world, and it will get so full of people that they won’t have room to stand beside each other.” In the meantime a young man came along the road, who was strong and healthy, singing a song, and glancing around on every side. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

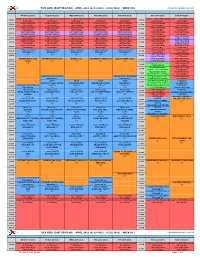

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

From Tenino to Ghana

Halloween Edition Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Battle of the Swamp W.F. West to Take On Centralia in Rivalry Classic / Inside Food Stamp Increase Expires REDUCTION: Cuts Depend the American Recovery and Rein- maximum benefit, for example, will vestment Act, which raised Supple- see a reduction of $29 a month from on Income, Expenses mental Nutrition Assistance Pro- $526 to $497. By Lisa Broadt gram benefits to help people affected A single adult receiving the maxi- by the recession. [email protected] mum benefit will go from $189 to Monthly food benefits vary based $178. The federal government’s tem- on factors such as income, living ex- Pete Caster / [email protected] Households that receive help porary boost in food assistance pro- penses and the number of people in through the state-funded Food Lisa and Jerry Morris stand outside the Lewis County oice of grams ends Friday. the household. the Department of Social and Health Service in Chehalis Oct. 2. In April 2009, Congress passed A family of three receiving the please see FOOD, page Main 11 Overbay, Students Gather Books and Supplies, Sending Support Others to Headline From Tenino to Ghana ‘Men’s Night Out’ ADVICE: Prostate Cancer Survivor, Lyle Overbay and Health Experts to Share Experiences at Tuesday Forum By Kyle Spurr [email protected] Arnie Guenther, a retired Centralia banker, avoided the doctor’s office for physical checkups until last year when his wife finally convinced him to make an appointment. Guenther felt fine, but results from the checkup showed he had prostate cancer. -

A Comparative Study of the Use of Folktales in Nazi Germany and in Contemporary Fiction for Young Adults

SPINNING THE WHEEL: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE USE OF FOLKTALES IN NAZI GERMANY AND IN CONTEMPORARY FICTION FOR YOUNG ADULTS by Kallie George B.A., University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Children's Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2007 © Kallie George, 2007 Abstract This thesis compares a selection of contemporary Holocaust novels for young adults that rework Grimm folklore to the Nazi regime's interpretation and propagandistic use of the same Grimm folklore. Using the methodology of intertextuality theory, in particular Julia Kristeva's concepts of monologic and dialogic discourse, this thesis examines the transformation of the Grimms' folktales "Hansel and Gretel," "Briar Rose," "Aschenputtel" and "Fitcher's Bird" in Louise Murphy's The True Story of Hansel and Gretel, Jane Yolen's Briar Rose and Peter Rushforth's Kindergarten. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract " Table of Contents iii Acknowledgements iv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Brothers Grimm 1 1.2 Folktales between the Era of the Brothers Grimm and the Nazi Era 9 1.3 Nazi Germany and the Use and Abuse of Folktales 12 1.4 Holocaust Literature for Children and Young Adults 15 1.5 Holocaust Novels by Louise Murphy, Jane Yolen and Peter Rushforth 23 1.6 Principal Research Questions 26 1.7 Methodology 28 2 Literature Review 31 2.1 Overview 31 2.2 Folklore Discourse and the Brothers Grimm : 31 2.3 Structuralism 33 2.4 Grimms' Retellings - Postmodernism -

The Vibrant Body of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales, Which Do Not

INTRODUCTION The Vibrant Body of the Grimms’ Folk and Fairy Tales, Which Do Not Belong to the Grimms The example of the Brothers Grimm had its imitators even in Russia, including the person of the first editor of Russian Folk Tales, A. N. Afanasyev. From the viewpoint of contemporary folkloristics, even a cautious reworking and stylization of the texts, written down from their performers, is considered absolutely inadmissible in scientific edi- tions. But in the era of the Brothers Grimm, in the world of romantic ideas and principles, this was altogether permissible. To the credit of the Brothers Grimm, it must be added that they were almost the first to establish the principle of publication of the authentic, popular oral poetic productions. — Y. M. Sokolov, Russian Folklore (1966)1 It is the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm who illustrate the connec- tion between folklore and textual criticism most powerfully, just as they demonstrate the continuing influence of Herder on thought. Nationalist politics and folkloric endeavours intertwine throughout all the Grimm brothers’ projects, but the Europe-wide significance of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen (first edition 1812) was the inspiration it provided to proto- folklorists to go out and collect “vom Volksmund,” that is from the mouth of the people (whether or not this was the Grimms’ own practice). — Timothy Baycroft and David Hopkin, Folklore and Nationalism in Europe During the Long Nineteenth Century (2012)2 Just what is a legacy, and what was the corpus of folk and fairy tales that the Broth- ers Grimm passed on to the German people—a corpus that grew, expanded, and eventually spread itself throughout the world? What do we mean when we talk about cultural legacy and memory? Why have the Grimms’ so- called German 1 2 INTRODUCTION tales spread throughout the world and become so universally international? Have the Grimms’ original intentions been betrayed? Did they betray them? If we fail to address these questions, the cultural legacy of the Grimms’ tales and their relevance cannot be grasped.