People and Trees: Providing Benefits, Overcoming Impediments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Forest Trees of NC

FFOORREESSTT TTRREEEESS OF NORTH CAROLINA North Carolina Forest Service TWENTIETH EDITION 2012 North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services The North Carolina Forest Service is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. Its programs, activities and employment practices are available to all people regardless of race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, handicap or political affiliation. COMMON FOREST TREES OF NORTH CAROLINA ( R E V I S E D ) A POCKET MANUAL Produced by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consum er Services North Carolina Forest Service Wib L. Owen, State Forester TWENTIETH EDITION 2012 Foreword Trees may be the oldest and largest living things in nature. They are closely associated with our daily lives, yet most of us know little about them and barely can tell one type of tree from another. Sixteen editions of this handy pocket guide have been printed since John Simcox Holmes, North Carolina's first State Forester, put together the first edition in 1922. Holmes' idea was to provide an easy-to-use reference guide to help people of all ages recognize many of our common forest trees on sight. That goal has not changed. Although the book has changed little, some uses of wood and general information about the trees have. Carriages and wagons, for example, aren't often made from Shagbark hickory (or anything else) anymore, and Loblolly pine now is used for making tremendous amounts of pine plywood, something unheard of in the 1920's. Keeping these changes in mind, we revised Common Forest Trees of North Carolina in 1977 and 1995. -

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

An Analysis of the Devil in the Original Folk and Fairy Tales

Syncretism or Superimposition: An Analysis of the Devil in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm Tiffany Stachnik Honors 498: Directed Study, Grimm’s Fairy Tales April 8, 2018 1 Abstract Since their first full publication in 1815, the folk and fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm have provided a means of studying the rich oral traditions of Germany. The Grimm brothers indicated time and time again in their personal notes that the oral traditions found in their folk and fairy tales included symbols, characters, and themes belonging to pre-Christian Germanic culture, as well as to the firmly Christian German states from which they collected their folk and fairy tales. The blending of pre-Christian Germanic culture with Christian, German traditions is particularly salient in the figure of the devil, despite the fact that the devil is arguably one of the most popular Christian figures to date. Through an exploration of the phylogenetic analyses of the Grimm’s tales featuring the devil, connections between the devil in the Grimm’s tales and other German or Germanic tales, and Christian and Germanic symbolism, this study demonstrates that the devil in the Grimm’s tales is an embodiment of syncretism between Christian and pre-Christian traditions. This syncretic devil is not only consistent with the history of religious transformation in Germany, which involved the slow blending of elements of Germanic paganism and Christianity, but also points to a greater theme of syncretism between the cultural traditions of Germany and other -

Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-Current

Sunshine Coast Street Tree Master Plan 2018 Part A: Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-current. Sunshine Coast Council™ is a registered trademark of Sunshine Coast Regional Council. www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au [email protected] T 07 5475 7272 F 07 5475 7277 Locked Bag 72 Sunshine Coast Mail Centre Qld 4560 Acknowledgements Council wishes to thank all contributors and stakeholders involved in the development of this document. Disclaimer Information contained in this document is based on available information at the time of writing. All figures and diagrams are indicative only and should be referred to as such. While the Sunshine Coast Regional Council has exercised reasonable care in preparing this document it does not warrant or represent that it is accurate or complete. Council or its officers accept no responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting in reliance upon any material contained in this document. Foreword Here on our healthy, smart, creative Sunshine Coast we are blessed with a wonderful environment. It is central to our way of life and a major reason why our 320,000 residents choose to live here – and why we are joined by millions of visitors each year. Although our region is experiencing significant population growth, we are dedicated to not only keeping but enhancing the outstanding characteristics that make this such a special place in the world. Our trees are the lungs of the Sunshine Coast and I am delighted that council has endorsed this master plan to increase the number of street trees across our region to balance our built environment. -

Lititz Borough Shade Tree List Growth Habit Key Columnar Vase Shaped

Lititz Borough Shade Tree List Growth Habit Key Columnar Vase Shaped Pyramidal Rounded Spreading Small Trees – Mature Height Less Than Thirty Feet (30’) Species Common Name Growth Habit Form Description Crategus Winter King Hawthorn 20-35’ Broad, round head Multi- viridis colored ‘Winter bark, King’ ornamental fruit Prunus x incam Okame Cherry 15-25’ Vase-shaped, Attractive bark; ‘Okame’ becoming rounded with pink flowers in age early spring Syringa reticulata Ivory Silk Tree Lilac 20-25’ Uniform rounded White flowers ‘Ivory Silk’ shape in mid- Summer Medium Trees – Approximate Mature Height of Thirty to Fifty Feet (30-50’) Species Common Name Growth habit Form Description Carpinus American Hornbeam 20-30’ Round spreading, caroliniana native, fall color, to compaction tolerant Gleditsia Thornless Honeylocust 30-40’ Pyramidal Small, lightweight triancanthos var. leaves; Golden yellow inermis fall color; Produces ‘Imperial’ , light shade ‘Skyline’, or ‘Moraine’ Nyssa sylvatica Blackgum 20-30’ Fall foliage includes many shades of yellow, orange, red, purple and scarlet Ostrya American Hophornbeam 25-40’ Pyramidal in youth Attractive bark and virginiana becoming broad hop- like fruit; native to Quercus Sawtooth Oak 35-40’ Pyramidal in youth, Yellow fall color; acutissima becoming rounded attractive bark; to acorns Large Trees – Mature Height Greater Than Fifty Feet (50’) Species Common Name Form Growth Habit Description Acer rubrum Columnar Red Maples 50-60’ Columnar Red flowers, fruit, and ‘Bowhall’ or fall color; native Armstrong Acer rubrum -

Download Season 5 Grimm Free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online

download season 5 grimm free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online. On Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, Nick struggles with how to move forward after the beheading of his mother, the death of Juliette and Adalind being pregnant. Watch Similar Shows FREE Amazon Watch Now iTunes Watch Now Vudu Watch Now YouTube Purchase Watch Now Google Play Watch Now NBC Watch Now Verizon On Demand Watch Now. When you watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 online, the action picks up right where the season finale of Grimm Season 4 left off, with Juliette dead in Nick's arms, Nick's mother's severed head in a box, and Agent Chavez's goons coming to kidnap Trubel. Nick is apparently drugged, and when he awakes, there is no sign that any of this occurred: no body, no box, no head, no Trubel. Was it all a truly horrible dream? Or part of a larger conspiracy? When he tries to tell his friends what happened, they hesitate to believe his claims, especially when he lays the blame at the feet of Agent Chavez. As his mental state deteriorates, will Nick be able to discover the truth about what happened and why? Where is Trubel now, and why did Chavez and her people come to kidnap her? Will his friends ever believe him, or will they continue to doubt his claims about what happened? And what will Nick do now that his and Adalind's baby is on the way? Tune in and watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, "The Grimm Identity," online right here at TV Fanatic to find out what happens. -

1812 GRIMM's FAIRY TALES DEATH's MESSENGERS Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm DEATHS MESSENGERS

1 1812 GRIMM’S FAIRY TALES DEATH’S MESSENGERS Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm Grimm, Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) - German philologists whose collection “Kinder- und Hausmarchen,” known in English as “Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” is a timeless literary masterpiece. The brothers transcribed these tales directly from folk and fairy stories told to them by common villagers. Death’s Messengers (1812) - Death is beaten by a giant then nursed back to life by a kind young man; Death pays the man back by promising to send messengers before coming to end his life. DEATHS MESSENGERS IN ANCIENT TIMES a giant was once traveling on a great highway, when suddenly an unknown man sprang up before him, and said, “Halt, not one step farther!” “What!” cried the giant, “a creature whom I can crush between my fingers, wants to block my way? Who art thou that thou darest to speak so boldly?” “I am Death,” answered the other. “No one resists me, and thou also must obey my commands.” But the giant refused, and began to struggle with Death. It was a long, violent battle. At last the giant got the upper hand, and struck Death down with his fist, so that he dropped by a stone. The giant went his way, and Death lay there conquered, and so weak that he could not get up again. “What will be done now,” said he, “if I stay lying here in a corner? No one will die now in the world, and it will get so full of people that they won’t have room to stand beside each other.” In the meantime a young man came along the road, who was strong and healthy, singing a song, and glancing around on every side. -

Maples in the Landscape Sheriden Hansen, Jaydee Gunnell, and Andra Emmertson

EXTENSION.USU.EDU Maples in the Landscape Sheriden Hansen, JayDee Gunnell, and Andra Emmertson Introduction Maple trees (Acer sp.) are a common fixture and beautiful addition to Utah landscapes. There are over one hundred species, each with numerous cultivars (cultivated varieties) that are native to both North America and much of Northern Europe. Trees vary in size and shape, from small, almost prostrate forms like certain Japanese maples (Acer palmatum) and shrubby bigtooth maples (Acer grandidentatum) to large and stately shade trees like the Norway maple (Acer platanoides). Tree shape can vary greatly, ranging from upright, columnar, rounded, pyramidal to spreading. Because trees come in a Figure 1. Severe iron chlorosis on maple. Note the range of shapes and sizes, there is almost always a interveinal chlorosis characterized by the yellow leaves spot in a landscape that can be enhanced by the and green veins. Spotting on the leaves is indicative of the addition of a maple. Maples can create a focal point beginning of tissue necrosis from a chronic lack of iron. and ornamental interest in the landscape, providing interesting textures and colors, and of course, shade. some micronutrients, particularly iron, to be less Fall colors typically range from yellow to bright red, available, making it difficult for certain trees to take adding a burst of color to the landscape late in the up needed nutrients. A common problem associated season. with maples in the Intermountain West is iron chlorosis (Figure 1). This nutrient deficiency causes Recommended Cultivars yellowing leaves (chlorosis) with green veins, and in extreme conditions, can cause death of leaf edges. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Shade Tree Info – the Maples

Shade Tree Info – The Maples Acer rubrum is commonly known as Red Maple, or Swamp Maple. Varieties of Acer rubrum offered by Four Seasons include: ‘Autumn Flame’ – one of the first Red Maples to show fall color, Autumn Flame has smaller leaves than most other Red Maples. The branching habit is excellent and the rate of growth is medium. The bright medium-red fall color occurs about 2 weeks earlier than ‘Red Sunset.’ Height x width in 20 years = 30-35’ x 30-35’ ‘Red Sunset’ (A. r. “Franksred’)– has consistently been rated as one of the top 5 shade trees in America since it’s introduction in the mid 1960’s. The clean green leaves turn a fiery orange-red every fall and the symmetrical branching of ‘Red Sunset’ make for a great specimen tree. Height x width in 20 years = 35-40’ x 30-35’ ‘October Glory’ – is the last of the Red Maples to show fall color, with leaves turning deep red about 2 weeks after ‘Red Sunset.’ As with all the rubrum Maples we offer, excellent branching structure and bright light gray bark is a trademark of ‘October Glory.’ Height x width in 20 years = 35-40’ x 30-35’ General notes: Acer rubrum varieties prefer moist soils (remember, they are also known as Swamp Maple) and they require a soil pH below 7. Therefore, rubrum Maples are NOT a good choice for planting in parkways where their roots will wander into the limestone base of a street. But for open lawn areas, they are beautiful trees, and the color they reliably achieve each fall is intense. -

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

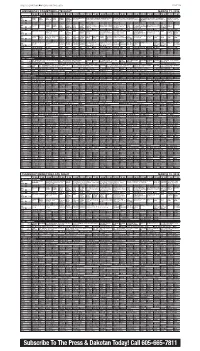

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Reommended Trees for Colo Front Range Communities.Pmd

Recommended Trees for Colorado Front Range Communities A Guide for Selecting, Planting, and Caring For Trees Do Not Top Your Trees! http://csfs.colostate.edu www.coloradotrees.org Trees that have been topped may become hazardous and unsightly. Avoid topping trees. Topping leads to: • Starvation www.fs.fed.us • Shock • Insects and diseases • Weak limbs • Rapid new growth • Tree death • Ugliness Special thanks to the International Society of Arboriculture for • Increased maintenance costs providing details and drawings for this brochure. Eastern redcedar* (Juniperus virginiana) Tree Selection Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree, green summer foliage, rusty brown in the winter Tree selection is one of the most important investment decisions a home owner makes when landscaping a new home or replacing a Rocky Mountain juniper* (Juniperus scopulorum) tree lost to damage or disease. Most trees can outlive the people Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree who plant them, therefore the impact of this decision is one that can influence a lifetime. Matching the tree to the site is critical; the following site and tree demands should be considered before buying and planting a tree. Trees to avoid! Site Considerations Selecting the right tree for the right place can help reduce the potential • Available space above and below ground for catastrophic loss of trees by insects, disease or environmental factors. We can’t control the weather, but we can use discernment in • Water availability selecting trees to plant. A variety of tree species should be planted so no • Drainage single species represents more than 10-15 percent of a community’s • Soil texture and pH total tree population.