THERMODYNAMICS, HEAT TRANSFER, and FLUID FLOW, Module 3 Fluid Flow Blank Fluid Flow TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Che 253M Experiment No. 2 COMPRESSIBLE GAS FLOW

Rev. 8/15 AD/GW ChE 253M Experiment No. 2 COMPRESSIBLE GAS FLOW The objective of this experiment is to familiarize the student with methods for measurement of compressible gas flow and to study gas flow under subsonic and supersonic flow conditions. The experiment is divided into three distinct parts: (1) Calibration and determination of the critical pressure ratio for a critical flow nozzle under supersonic flow conditions (2) Calculation of the discharge coefficient and Reynolds number for an orifice under subsonic (non- choked) flow conditions and (3) Determination of the orifice constants and mass discharge from a pressurized tank in a dynamic bleed down experiment under (choked) flow conditions. The experimental set up consists of a 100 psig air source branched into two manifolds: the first used for parts (1) and (2) and the second for part (3). The first manifold contains a critical flow nozzle, a NIST-calibrated in-line digital mass flow meter, and an orifice meter, all connected in series with copper piping. The second manifold contains a strain-gauge pressure transducer and a stainless steel tank, which can be pressurized and subsequently bled via a number of attached orifices. A number of NIST-calibrated digital hand held manometers are also used for measuring pressure in all 3 parts of this experiment. Assorted pressure regulators, manual valves, and pressure gauges are present on both manifolds and you are expected to familiarize yourself with the process flow, and know how to operate them to carry out the experiment. A process flow diagram plus handouts outlining the theory of operation of these devices are attached. -

Stall/Surge Dynamics of a Multi-Stage Air Compressor in Response to a Load Transient of a Hybrid Solid Oxide Fuel Cell-Gas Turbine System

Journal of Power Sources 365 (2017) 408e418 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Power Sources journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpowsour Stall/surge dynamics of a multi-stage air compressor in response to a load transient of a hybrid solid oxide fuel cell-gas turbine system * Mohammad Ali Azizi, Jacob Brouwer Advanced Power and Energy Program, University of California, Irvine, USA highlights Dynamic operation of a hybrid solid oxide fuel cell gas turbine system was explored. Computational fluid dynamic simulations of a multi-stage compressor were accomplished. Stall/surge dynamics in response to a pressure perturbation were evaluated. The multi-stage radial compressor was found robust to the pressure dynamics studied. Air flow was maintained positive without entering into severe deep surge conditions. article info abstract Article history: A better understanding of turbulent unsteady flows in gas turbine systems is necessary to design and Received 14 August 2017 control compressors for hybrid fuel cell-gas turbine systems. Compressor stall/surge analysis for a 4 MW Accepted 4 September 2017 hybrid solid oxide fuel cell-gas turbine system for locomotive applications is performed based upon a 1.7 MW multi-stage air compressor. Control strategies are applied to prevent operation of the hybrid SOFC-GT beyond the stall/surge lines of the compressor. Computational fluid dynamics tools are used to Keywords: simulate the flow distribution and instabilities near the stall/surge line. The results show that a 1.7 MW Solid oxide fuel cell system compressor like that of a Kawasaki gas turbine is an appropriate choice among the industrial Hybrid fuel cell gas turbine Dynamic simulation compressors to be used in a 4 MW locomotive SOFC-GT with topping cycle design. -

CFD Based Design for Ejector Cooling System Using HFOS (1234Ze(E) and 1234Yf)

energies Article CFD Based Design for Ejector Cooling System Using HFOS (1234ze(E) and 1234yf) Anas F A Elbarghthi 1,*, Saleh Mohamed 2, Van Vu Nguyen 1 and Vaclav Dvorak 1 1 Department of Applied Mechanics, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Liberec, Studentská 1402/2, 46117 Liberec, Czech Republic; [email protected] (V.V.N.); [email protected] (V.D.) 2 Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Masdar Institute, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, UAE; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 February 2020; Accepted: 14 March 2020; Published: 18 March 2020 Abstract: The field of computational fluid dynamics has been rekindled by recent researchers to unleash this powerful tool to predict the ejector design, as well as to analyse and improve its performance. In this paper, CFD simulation was conducted to model a 2-D axisymmetric supersonic ejector using NIST real gas model integrated in ANSYS Fluent to probe the physical insight and consistent with accurate solutions. HFOs (1234ze(E) and 1234yf) were used as working fluids for their promising alternatives, low global warming potential (GWP), and adhering to EU Council regulations. The impact of different operating conditions, performance maps, and the Pareto frontier performance approach were investigated. The expansion ratio of both refrigerants has been accomplished in linear relationship using their critical compression ratio within 0.30% accuracy. The results show that ± R1234yf achieved reasonably better overall performance than R1234ze(E). Generally, by increasing the primary flow inlet saturation temperature and pressure, the entrainment ratio will be lower, and this allows for a higher critical operating back pressure. -

MSME with Depth in Fluid Mechanics

MSME with depth in Fluid Mechanics The primary areas of fluid mechanics research at Michigan State University's Mechanical Engineering program are in developing computational methods for the prediction of complex flows, in devising experimental methods of measurement, and in applying them to improve understanding of fluid-flow phenomena. Theoretical fluid dynamics courses provide a foundation for this research as well as for related studies in areas such as combustion, heat transfer, thermal power engineering, materials processing, bioengineering and in aspects of manufacturing engineering. MS Track for Fluid Mechanics The MSME degree program for fluid mechanics is based around two graduate-level foundation courses offered through the Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME). These courses are ME 830 Fluid Mechanics I Fall ME 840 Computational Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer Spring The ME 830 course is the basic graduate level course in the continuum theory of fluid mechanics that all students should take. In the ME 840 course, the theoretical understanding gained in ME 830 is supplemented with material on numerical methods, discretization of equations, and stability constraints appropriate for developing and using computational methods of solution to fluid mechanics and convective heat transfer problems. Students augment these courses with additional courses in fluid mechanics and satisfy breadth requirements by selecting courses in the areas of Thermal Sciences, Mechanical and Dynamical Systems, and Solid and Structural Mechanics. Graduate Course and Research Topics (Profs. Benard, Brereton, Jaberi, Koochesfahani, Naguib) ExperimentalResearch Many fluid flow phenomena are too complicated to be understood fully or predicted accurately by either theory or computational methods. Sometimes the boundary conditions of real-world problems cannot be analyzed accurately. -

Heat Transfer in Flat-Plate Solar Air-Heating Collectors

Advanced Computational Methods in Heat Transfer VI, C.A. Brebbia & B. Sunden (Editors) © 2000 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISBN 1-85312-818-X Heat transfer in flat-plate solar air-heating collectors Y. Nassar & E. Sergievsky Abstract All energy systems involve processes of heat transfer. Solar energy is obviously a field where heat transfer plays crucial role. Solar collector represents a heat exchanger, in which receive solar radiation, transform it to heat and transfer this heat to the working fluid in the collector's channel The radiation and convection heat transfer processes inside the collectors depend on the temperatures of the collector components and on the hydrodynamic characteristics of the working fluid. Economically, solar energy systems are at best marginal in most cases. In order to realize the potential of solar energy, a combination of better design and performance and of environmental considerations would be necessary. This paper describes the thermal behavior of several types of flat-plate solar air-heating collectors. 1 Introduction Nowadays the problem of utilization of solar energy is very important. By economic estimations, for the regions of annual incident solar radiation not less than 4300 MJ/m^ pear a year (i.e. lower 60 latitude), it will be possible to cover - by using an effective flat-plate solar collector- up to 25% energy demand in hot water supply systems and up to 75% in space heating systems. Solar collector is the main element of any thermal solar system. Besides of large number of scientific publications, on the problem of solar energy utilization, for today there is no common satisfactory technique to evaluate the thermal behaviors of solar systems, especially the local characteristics of the solar collector. -

Manual for Lab #2

CE 321 INTRODUCTION TO FLUID MECHANICS Fall 2009 LABORATORY 3: THE BERNOULLI EQUATION OBJECTIVES To investigate the validity of Bernoulli's Equation as applied to the flow of water in a tapering horizontal tube to determine if the total pressure head remains constant along the length of the tube as the equation predicts. To determine if the variations in static pressure head along the length of the tube can be predicted with Bernoulli’s equation APPROACH Establish a constant flow rate (Q) through the tube and measure it. Use a pitot probe and static probe to measure the total pressure head h Tm and static pressure head h Sm at six locations along the length of the tube. The values of h Tm will show if total pressure head remains constant along the length of the tube as required by the Bernoulli Equation. Using the flow rate and cross sectional area of the tube, calculate the velocity head h Vc at each location. Use Bernoulli’s Equation, h Tm and h Vc to predict the variations in static pressure head h St expected along the tube. Compare the calculated and measured values of static pressure head to determine if the variations in fluid pressure along the length of the tube can be predicted with Bernoulli’s Equation. EQUIPMENT Hydraulic bench with Bernoulli apparatus, stop watch THEORY Considering flow at any two positions on the central streamline of the tube (Fig. 1), Bernoulli's equation may be written as V 2 p V 2 p 1 + 1 + z = 2 + 2 + z (1) 2g γ 1 2g γ 2 1 Bernoulli’s equation indicates that the sum of the velocity head (V 2/2g), pressure head (p/ γ), and elevation (z) are constant along the central streamline. -

Chapter 1 PROPERTIES of FLUID & PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

Fluid Mechanics & Machinery Chapter 1 PROPERTIES OF FLUID & PRESSURE MEASUREMENT Course Contents 1. Introduction 2. Properties of Fluid 2.1 Density 2.2 Specific gravity 2.3 Specific volume 2.4 Specific Weight 2.5 Dynamic viscosity 2.6 Kinematic viscosity 2.7 Surface tension 2.8 Capillarity 2.9 Vapor Pressure 2.10 Compressibility 3. Fluid Pressure & Pressure Measurement 3.1 Fluid pressure, Pressure head, Pascal‟s law 3.2 Concept of absolute vacuum, gauge pressure, atmospheric pressure, absolute pressure. 3.3 Pressure measuring Devices 3.4 Simple and differential manometers, 3.5 Bourdon pressure gauge. 4. Total pressure, center of pressure 4.1 Total pressure, center of pressure 4.2 Horizontal Plane Surface Submerged in Liquid 4.3 Vertical Plane Surface Submerged in Liquid 4.4 Inclined Plane Surface Submerged in Liquid MR. R. R. DHOTRE (8888944788) Page 1 Fluid Mechanics & Machinery 1. Introduction Fluid mechanics is a branch of engineering science which deals with the behavior of fluids (liquid or gases) at rest as well as in motion. 2. Properties of Fluids 2.1 Density or Mass Density -Density or mass density of fluid is defined as the ratio of the mass of the fluid to its volume. Mass per unit volume of a fluid is called density. -It is denoted by the symbol „ρ‟ (rho). -The unit of mass density is kg per cubic meter i.e. kg/m3. -Mathematically, ρ = -The value of density of water is 1000 kg/m3, density of Mercury is 13600 kg/m3. 2.2 Specific Weight or Weight Density -Specific weight or weight density of a fluid is defined as the ratio of weight of a fluid to its volume. -

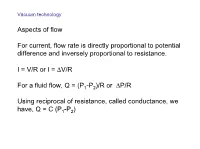

Aspects of Flow for Current, Flow Rate Is Directly Proportional to Potential

Vacuum technology Aspects of flow For current, flow rate is directly proportional to potential difference and inversely proportional to resistance. I = V/R or I = V/R For a fluid flow, Q = (P1-P2)/R or P/R Using reciprocal of resistance, called conductance, we have, Q = C (P1-P2) There are two kinds of flow, volumetric flow and mass flow Volume flow rate, S = vA v – the average bulk velocity, A the cross sectional area S = V/t, V is the volume and t is the time. Mass flow rate is S x density. G = vA or V/t Mass flow rate is measured in units of throughput, such as torr.L/s Throughput = volume flow rate x pressure Throughput is equivalent to power. Torr.L/s (g/cm2)cm3/s g.cm/s J/s W It works out that, 1W = 7.5 torr.L/s Types of low 1. Laminar: Occurs when the ratio of mass flow to viscosity (Reynolds number) is low for a given diameter. This happens when Reynolds number is approximately below 2000. Q ~ P12-P22 2. Above 3000, flow becomes turbulent Q ~ (P12-P22)0.5 3. Choked flow occurs when there is a flow restriction between two pressure regions. Assume an orifice and the pressure difference between the two sections, such as 2:1. Assume that the pressure in the inlet chamber is constant. The flow relation is, Q ~ P1 4. Molecular flow: When pressure reduces, MFP becomes larger than the dimensions of the duct, collisions occur between the walls of the vessel. -

Sensitivity Analysis of Non-Linear Steep Waves Using VOF Method

Tenth International Conference on ICCFD10-268 Computational Fluid Dynamics (ICCFD10), Barcelona, Spain, July 9-13, 2018 Sensitivity Analysis of Non-linear Steep Waves using VOF Method A. Khaware*, V. Gupta*, K. Srikanth *, and P. Sharkey ** Corresponding author: [email protected] * ANSYS Software Pvt Ltd, Pune, India. ** ANSYS UK Ltd, Milton Park, UK Abstract: The analysis and prediction of non-linear waves is a crucial part of ocean hydrodynamics. Sea waves are typically non-linear in nature, and whilst models exist to predict their behavior, limits exist in their applicability. In practice, as the waves become increasingly steeper, they approach a point beyond which the wave integrity cannot be maintained, and they 'break'. Understanding the limits of available models as waves approach these break conditions can significantly help to improve the accuracy of their potential impact in the field. Moreover, inaccurate modeling of wave kinematics can result in erroneous hydrodynamic forces being predicted. This paper investigates the sensitivity of non-linear wave modeling from both an analytical and a numerical perspective. Using a Volume of Fluid (VOF) method, coupled with the Open Channel Flow module in ANSYS Fluent, sensitivity studies are performed for a variety of non-linear wave scenarios with high steepness and high relative height. These scenarios are intended to mimic the near-break conditions of the wave. 5th order solitary wave models are applied to shallow wave scenarios with high relative heights, and 5th order Stokes wave models are applied to short gravity waves with high wave steepness. Stokes waves are further applied in the shallow regime at high wave steepness to examine the wave sensitivity under extreme conditions. -

Heat Transfer (Heat and Thermodynamics)

Heat Transfer (Heat and Thermodynamics) Wasif Zia, Sohaib Shamim and Muhammad Sabieh Anwar LUMS School of Science and Engineering August 7, 2011 If you put one end of a spoon on the stove and wait for a while, your nger tips start feeling the burn. So how do you explain this simple observation in terms of physics? Heat is generally considered to be thermal energy in transit, owing between two objects that are kept at di erent temperatures. Thermodynamics is mainly con- cerned with objects in a state of equilibrium, while the subject of heat transfer probes matter in a state of disequilibrium. Heat transfer is a beautiful and astound- ingly rich subject. For example, heat transfer is inextricably linked with atomic and molecular vibrations; marrying thermal physics with solid state physics|the study of the structure of matter. We all know that owing matter (such as air) in contact with a heated object can help `carry the heat away'. The motion of the uid, its turbulence, the ow pattern and the shape, size and surface of the object can have a pronounced e ect on how heat is transferred. These heat ow mechanisms are also an essential part of our ventilation and air conditioning mechanisms, adding comfort to our lives. Importantly, without heat exchange in power plants it is impossible to think of any power generation, without heat transfer the internal combustion engine could not drive our automobiles and without it, we would not be able to use our computer for long and do lengthy experiments (like this one!), without overheating and frying our electronics. -

(CFD) Modelling and Application for Sterilization of Foods: a Review

processes Review Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Modelling and Application for Sterilization of Foods: A Review Hyeon Woo Park and Won Byong Yoon * ID Department of Food Science and Biotechnology, College of Agricultural and Life Science, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-33-250-6459 Received: 30 March 2018; Accepted: 23 May 2018; Published: 24 May 2018 Abstract: Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a powerful tool to model fluid flow motions for momentum, mass and energy transfer. CFD has been widely used to simulate the flow pattern and temperature distribution during the thermal processing of foods. This paper discusses the background of the thermal processing of food, and the fundamentals in developing CFD models. The constitution of simulation models is provided to enable the design of effective and efficient CFD modeling. An overview of the current CFD modeling studies of thermal processing in solid, liquid, and liquid-solid mixtures is also provided. Some limitations and unrealistic assumptions faced by CFD modelers are also discussed. Keywords: computational fluid dynamics; CFD; thermal processing; sterilization; computer simulation 1. Introduction In the food industry, thermal processing, including sterilization and pasteurization, is defined as the process by which there is the application of heat to a food product in a container, in an effort to guarantee food safety, and extend the shelf-life of processed foods [1]. Thermal processing is the most widely used preservation technology to safely produce long shelf-lives in many kinds of food, such as fruits, vegetables, milk, fish, meat and poultry, which would otherwise be quite perishable. -

Waves and Structures

WAVES AND STRUCTURES By Dr M C Deo Professor of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Bombay Powai, Mumbai 400 076 Contact: [email protected]; (+91) 22 2572 2377 (Please refer as follows, if you use any part of this book: Deo M C (2013): Waves and Structures, http://www.civil.iitb.ac.in/~mcdeo/waves.html) (Suggestions to improve/modify contents are welcome) 1 Content Chapter 1: Introduction 4 Chapter 2: Wave Theories 18 Chapter 3: Random Waves 47 Chapter 4: Wave Propagation 80 Chapter 5: Numerical Modeling of Waves 110 Chapter 6: Design Water Depth 115 Chapter 7: Wave Forces on Shore-Based Structures 132 Chapter 8: Wave Force On Small Diameter Members 150 Chapter 9: Maximum Wave Force on the Entire Structure 173 Chapter 10: Wave Forces on Large Diameter Members 187 Chapter 11: Spectral and Statistical Analysis of Wave Forces 209 Chapter 12: Wave Run Up 221 Chapter 13: Pipeline Hydrodynamics 234 Chapter 14: Statics of Floating Bodies 241 Chapter 15: Vibrations 268 Chapter 16: Motions of Freely Floating Bodies 283 Chapter 17: Motion Response of Compliant Structures 315 2 Notations 338 References 342 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction The knowledge of magnitude and behavior of ocean waves at site is an essential prerequisite for almost all activities in the ocean including planning, design, construction and operation related to harbor, coastal and structures. The waves of major concern to a harbor engineer are generated by the action of wind. The wind creates a disturbance in the sea which is restored to its calm equilibrium position by the action of gravity and hence resulting waves are called wind generated gravity waves.