Pirate Strategies Database and Distributed Over the Boundless.Coop Wireless Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Foster Carries on Hating Keith Listens To

April 2017 April 96 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Chuck Berry, Capital Radio Jazzfest, Alexandra Palace, London, 21-07-79, © Paul Harris Neil Foster carries on hating Keith listens to John Broven The Frogman's Surprise Birthday Party We “borrow” more stuff from Nick Cobban Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 2 An unidentified man spotted by Bill Haynes stuffing a pie into his face outside Wilton’s Music Hall mumbles: “ HOLD THE THIRD PAGE! ” Hi Gang, Trust you are all well and as fluffy as little bunnies for our spring edition of Tales From The Woods Magazine. WOW, what a night!! I'm talking about Sunday 19th March at Soho's Spice Of Life venue. Charlie Gracie and the TFTW Band put on a show to remember, Yes, another triumph for us, just take a look at the photo of Charlie on stage at the Spice, you can see he was having a ball, enjoying the appreciation of the audience as much as they were enjoying him. You can read a review elsewhere within these pages, so I won’t labour the point here, except to offer gratitude to Charlie and the Tales From The Woods Band for making the evening so special, in no small part made possible by David the excellent sound engineer whom we request by name for our shows. As many of you have experienced at Rock’n’Roll shows, many a potentially brilliant set has been ruined by poor © Paul Harris sound, or literally having little idea how to sound up a vintage Rock’n’Roll gig. -

PROTOCOLOS E CÓDIGOS NA ESFERA PÚBLICA INTERCONECTADA Revista De Sociologia E Política, Vol

Revista de Sociologia e Política ISSN: 0104-4478 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Paraná Brasil Silveira, Sergio Amadeu da NOVAS DIMENSÕES DA POLÍTICA: PROTOCOLOS E CÓDIGOS NA ESFERA PÚBLICA INTERCONECTADA Revista de Sociologia e Política, vol. 17, núm. 34, octubre, 2009, pp. 103-113 Universidade Federal do Paraná Curitiba, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=23816088008 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto REVISTA DE SOCIOLOGIA E POLÍTICA V. 17, Nº 34 : 103-113 OUT. 2009 NOVAS DIMENSÕES DA POLÍTICA: PROTOCOLOS E CÓDIGOS NA ESFERA PÚBLICA INTERCONECTADA Sergio Amadeu da Silveira RESUMO O texto propõe a existência de uma divisão básica na relação entre política e Internet: a política “da” Internet e a política “na” Internet. Em seguida, agrega os temas das políticas da internet em três campos de disputas fundamentais: sobre a infra-estrutura da rede; sobre os formatos, padrões e aplicações; e sobre os conteúdos. Analisa os temas políticos atuais mais relevantes de cada campo conflituoso, articulando dois aspectos: o tecno-social e o jurídico-legislativo. Este artigo trabalha com o conceito de arquitetura de poder, uma extensão da definição de Alexander Galloway sobre o gerenciamento protocolar, e com a perspectiva de Yochai Benkler sobre a existência de uma esfera pública interconectada. Sua conclusão indica que a liberdade nas redes cibernéticas depende da existência da navegação não-identificada, ou seja, do anonimato. -

The Truth About Big Oil and Climate Change РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS Is the German model broken? Iran, 40 years after the revolution China’s embrace of intellectual property On the economics of species FEBRUARY 9TH–15TH 2019 Crude awakening The truth about Big Oil and climate change РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS World-Leading Cyber AI РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News" VK.COM/WSNWS Contents The Economist February 9th 2019 3 The world this week United States 6 A round-up of political 19 After the INF treaty and business news 20 Missiles and mistrust 21 Virginia and shoe polish Leaders 21 Union shenanigans 9 Energy and climate Crude awakening 22 Botox bars Elizabeth Warren’s ideas 10 Germany’s economy 23 Time to worry 24 Lexington Donald Trump and conservatism 10 Arms control Death of a nuclear pact The Americas 12 Iran’s revolution at 40 Dealing with the mullahs 25 Canada in the global jungle On the cover 13 A new boss for the World Bank 26 Jair Bolsonaro’s The oil industry is making a A qualified pass congressional win bet that could wreck the 28 Bello The Venezuelan climate: leader, page 9. Letters dinosaur ExxonMobil, a fossil-fuel On the Democratic titan, gambles on growth: 14 Republic of Congo, Asia Briefing, page 16. The Green hygiene, Brexit, chicken, New Deal pays little heed to 29 India’s Congress party King Crimson, airlines economic orthodoxy: Free 30 Avoiding military service exchange, page 67 in South Korea Briefing • Is the German model broken? 31 Turmoil in Thai politics 16 ExxonMobil An economic golden age could 31 Facial fashions in Bigger oil, amid efforts to be coming to an end: leader, Pakistan hold back climate change page 10. -

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

A Remix Manifesto

An Educational Guide About The Film In RiP: A remix manifesto, web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers. The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash‐up musician topping the charts with his sample‐based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil, and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow also come along for the ride. This is a participatory media experiment from day one, in which Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org for anyone to remix. This movie‐as‐mash‐up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle. Which side of the ideas war are you on? About The Guide While the film is best viewed in its entirety, the chapters have been summarized, and relevant discussion questions are provided for each. Many questions specifically relate to music or media studies but some are more general in nature. General questions may still be relevant to the arts, but cross over to social studies, law and current events. Selected resources are included at the end of the guide to help students with further research, and as references for material covered in the documentary. This guide was written and compiled by Adam Hodgins, a teacher of Music and Technology at Selwyn House School in Montreal, Quebec. -

IKF ITT Maps A3 X6

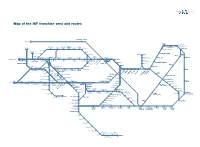

51 Map of the IKF franchise area and routes Stratford International St Pancras Margate Dumpton Park (limited service) Westcombe Woolwich Woolwich Abbey Broadstairs Park Charlton Dockyard Arsenal Plumstead Wood Blackfriars Belvedere Ramsgate Westgate-on-Sea Maze Hill Cannon Street Erith Greenwich Birchington-on-Sea Slade Green Sheerness-on-Sea Minster Deptford Stone New Cross Lewisham Kidbrooke Falconwood Bexleyheath Crossing Northfleet Queenborough Herne Bay Sandwich Charing Cross Gravesend Waterloo East St Johns Blackheath Eltham Welling Barnehurst Dartford Swale London Bridge (to be closed) Higham Chestfield & Swalecliffe Elephant & Castle Kemsley Crayford Ebbsfleet Greenhithe Sturry Swanscombe Strood Denmark Bexley Whitstable Hill Nunhead Ladywell Hither Green Albany Park Deal Peckham Rye Crofton Catford Lee Mottingham New Eltham Sidcup Bridge am Park Grove Park ham n eynham Selling Catford Chath Rai ngbourneT Bellingham Sole Street Rochester Gillingham Newington Faversham Elmstead Woods Sitti Canterbury West Lower Sydenham Sundridge Meopham Park Chislehurst Cuxton New Beckenham Bromley North Longfield Canterbury East Beckenham Ravensbourne Brixton West Dulwich Penge East Hill St Mary Cray Farnigham Road Halling Bekesbourne Walmer Victoria Snodland Adisham Herne Hill Sydenham Hill Kent House Beckenham Petts Swanley Chartham Junction uth Eynsford Clock House Wood New Hythe (limited service) Aylesham rtlands Bickley Shoreham Sho Orpington Aylesford Otford Snowdown Bromley So Borough Chelsfield Green East Malling Elmers End Maidstone -

Remix and Rebalance: Copyright and Fair Use Issues in the Digital Age and English Studies Scott A

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects 4-1-2013 Remix and Rebalance: Copyright and Fair Use Issues in the Digital Age and English Studies Scott A. inS gleton Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Singleton, Scott A., "Remix and Rebalance: Copyright and Fair Use Issues in the Digital Age and English Studies" (2013). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 558. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. Remix and Rebalance: Copyright and Fair Use Issues in the Digital Age and English Studies By Scott A. Singleton A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in The Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2013 3 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Writing in the Twenty‐First Century 10 Chapter 2: Creativity 19 Chapter 3: Remix 24 Chapter 4: Plagiarism 28 Chapter 5: Fair Use 35 Chapter 6: The Original Purpose of Copyright 44 Chapter 7: Creative Commons 51 Conclusion 53 Appendix A: Three Mini‐Lessons 56 Appendix B: Three Small Assignments 61 Works Cited for Appendices A and B 67 Additional Resources 68 Works Cited 69 Curriculum Vitae 73 4 Introduction “Never in our history have fewer had a legal right to control more of the development of our culture than now.” – Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture This thesis addresses both the need and specific ways to increase conversations on copyright law, fair use, and intellectual property in the composition classroom. -

Hacker Culture & Politics

HACKER CULTURE & POLITICS COMS 541 (CRN 15368) 1435-1725 Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University Professor Gabriella Coleman Fall 2012 Arts W-220/ 14:35-17:25 Professor: Dr. Gabriella Coleman Office: Arts W-110 Office hours: Sign up sheet Tuesday 2:30-3:30 PM Phone: xxx E-mail: [email protected] OVERVIEW This course examines computer hackers to interrogate not only the ethics and technical practices of hacking, but to examine more broadly how hackers and hacking have transformed the politics of computing and the Internet more generally. We will examine how hacker values are realized and constituted by different legal, technical, and ethical activities of computer hacking—for example, free software production, cyberactivism and hactivism, cryptography, and the prankish games of hacker underground. We will pay close attention to how ethical principles are variably represented and thought of by hackers, journalists, and academics and we will use the example of hacking to address various topics on law, order, and politics on the Internet such as: free speech and censorship, privacy, security, surveillance, and intellectual property. We finish with an in-depth look at two sites of hacker and activist action: Wikileaks and Anonymous. LEARNER OBJECTIVES This will allow us to 1) demonstrate familiarity with variants of hacking 2) critically examine the multiple ways hackers draw on and reconfigure dominant ideas of property, freedom, and privacy through their diverse moral 1 codes and technical activities 3) broaden our understanding of politics of the Internet by evaluating the various political effects and ramifications of hacking. -

Selected Filmography of Digital Culture and New Media Art

Dejan Grba SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY OF DIGITAL CULTURE AND NEW MEDIA ART This filmography comprises feature films, documentaries, TV shows, series and reports about digital culture and new media art. The selected feature films reflect the informatization of society, economy and politics in various ways, primarily on the conceptual and narrative plan. Feature films that directly thematize the digital paradigm can be found in the Film Lists section. Each entry is referenced with basic filmographic data: director’s name, title and production year, and production details are available online at IMDB, FilmWeb, FindAnyFilm, Metacritic etc. The coloured titles are links. Feature films Fritz Lang, Metropolis, 1926. Fritz Lang, M, 1931. William Cameron Menzies, Things to Come, 1936. Fritz Lang, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, 1960. Sidney Lumet, Fail-Safe, 1964. James B. Harris, The Bedford Incident, 1965. Jean-Luc Godard, Alphaville, 1965. Joseph Sargent, Colossus: The Forbin Project, 1970. Henri Verneuil, Le serpent, 1973. Alan J. Pakula, The Parallax View, 1974. Francis Ford Coppola, The Conversation, 1974. Sidney Pollack, The Three Days of Condor, 1975. George P. Cosmatos, The Cassandra Crossing, 1976. Sidney Lumet, Network, 1976. Robert Aldrich, Twilight's Last Gleaming, 1977. Michael Crichton, Coma, 1978. Brian De Palma, Blow Out, 1981. Steven Lisberger, Tron, 1982. Godfrey Reggio, Koyaanisqatsi, 1983. John Badham, WarGames, 1983. Roger Donaldson, No Way Out, 1987. F. Gary Gray, The Negotiator, 1988. John McTiernan, Die Hard, 1988. Phil Alden Robinson, Sneakers, 1992. Andrew Davis, The Fugitive, 1993. David Fincher, The Game, 1997. David Cronenberg, eXistenZ, 1999. Frank Oz, The Score, 2001. Tony Scott, Spy Game, 2001. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2016, London

London Register 2016 HERITAGE AT RISK 2016 / LONDON Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Reducing the risks XI Key statistics XIV Publications and guidance XV Key to the entries XVII Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Greater London 1 Barking and Dagenham 1 Barnet 2 Bexley 5 Brent 5 Bromley 6 Camden 11 City of London 20 Croydon 21 Ealing 24 Enfield 27 Greenwich 30 Hackney 34 Hammersmith and Fulham 40 Haringey 43 Harrow 47 Havering 50 Hillingdon 51 Hounslow 58 Islington 64 Kensington and Chelsea 70 Kingston upon Thames 81 Lambeth 82 Lewisham 91 London Legacy (MDC) 95 Merton 96 Newham 101 Redbridge 103 Richmond upon Thames 104 Southwark 108 Sutton 116 Tower Hamlets 117 Waltham Forest 123 Wandsworth 126 Westminster, City of 129 II London Summary 2016 he Heritage at Risk Register in London reflects the diversity of our capital’s historic environment. It includes 682 buildings and sites known to be at risk from Tneglect, decay or inappropriate development - everything from an early 18th century church designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, to a boathouse built during WWI on an island in the Thames. These are sites that need imagination and investment. In London the scale of this challenge has grown. There are 12 more assets on the Heritage at Risk Register this year compared to 2015. We also know that it’s becoming more expensive to repair many of our buildings at risk. In the face of these challenges we’re grateful for the help and support of all those who continue to champion our historic environment. -

Buses from Catford East

Buses from Catford East Key N171 continues to 181 284 202 Lewisham Tottenham Court Road D Blackheath 124 Day buses in black Royal Standard Camberwell Green N171 Night buses in blue O Connections with London Underground Lewisham Prince Charles Road — Town Centre o Connections with London Overground Peckham Road R Connections with National Rail Lewisham Courthill Road DI Connections with Docklands Light Railway Leisure Centre Blackheath B Connections with river boats Peckham Ladywell Hither Green Lane Town Centre Thornford Road Ladywell Road Wearside Road Lee Road Chudleigh Road Manor Way QueenÕs Road Peckham Phoebeth Road Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus Hither Green Lane service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop in the Theodore Road Chudleigh Road Burnt Ash Road street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). Foxborough Gardens N171 Lee Road New Cross Hither Green Lane Hither Green Bus Garage Bexhill Road George Lane Hail & RideManwood section Road Burnt Ash Road Micheldever Road Ravensbourne Park Hither Green Lane Route finder New Cross Gate Bankhurst Road Duncrievie Road Day buses Lee Ravensbourne Park Catford Road Bus route Towards Bus stops Brockley Cross Torridon Road 124 Catford UWXY for Brockley Hither Green Lane Burnt Ash Hill Ravensbourne Park 'P1ndar Westhorne Avenue Eltham HJST D Playing Fields Westdown Road A F St Mildreds Road O Baring Road Westhorne Avenue Middle Park Avenue Catford VWXY R C G 160 D Horn Park Lane Kingsground Crofton Park ROAD D BROWNHILL Sidcup HJKL R A St Mildreds Road Westhorne Avenue Eltham Ravensbourne Park M M D B A N Eltham Plassy Road B T. -

Collisions. Parks Bridge Junction and Bromley Junction

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT RAILWAY ACCIDENT Report on the Collisions that occurred on 18th August 1981 at Parks Bridge Junction and on 13th November 1981 at Bromley Junction IN THE SOUTHERN REGION OF BRITISH RAILWAYS LONDON: HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE RAILWAYINSPLC IORAT~, DEPARTMEYI ok TRANSPORT, 2 MARSHAMSTKFET. LONDONSWlP3EB, 15th December 1983 SIR, I have the honour to report for the information of the Secretary of State in accordance with the Direction dated 27th August, 1981, the result of my Inquiry into the collision between two electric passenger trains at 08.05 on Tuesday, 18th August, 1981. at Parks Bridge Junction. between London Bridge and Hither Green, and in accordance with the Direction dated 19th November, 1981, the result of my Inquiry into the collision between two electric passenger trains at 08.28 on Friday, 13th November, 1981, at Bromley Junction, between Norwood Junction and Crystal Palace, in the Southern Region of British Railways. Although the two collisions were not directly connected. thev were in manv, wavs, similar and thus I consider itappropriate to deal with both the acfidents in a sing]; report with conclusions, remarks and recommendations drawn from the Inquiry into each accident as is appropriate. In the first collision, the driver of the 07.49 Charing Cross to Bromley North electric multiple-unit passenger train, 2504, consisting of eight coaches and travelling on the Down Fast line, passed a signal at Danger and observed the 06.18 Dover Priory to Cannon Street electric multiple-unit express passenger train, 1G51, consisting of twelve coaches, crossing from the Up Fast line to the Up Slow line ahead of him.