Anarchy No. 42

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/hums-4904a-schedule-mondays-11-35-2-25-each-session-is-in-two-halves-a-and-b-86562.webp)

HUMS 4904A Schedule Mondays 11:35 - 2:25 [Each Session Is in Two Halves: a and B]

CARLETON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES Humanities 4904 A (Winter 2011) Mahatma Gandhi Across Cultures Mondays 11:35-2:25 Prof. Noel Salmond Paterson Hall 2A46 Paterson Hall 2A38 520-2600 ext. 8162 [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays 2:00 - 4:00 (Or by appointment) This seminar is a critical examination of the life and thought of one of the pivotal and iconic figures of the twentieth century, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – better known as the Mahatma, the great soul. Gandhi is a bridge figure across cultures in that his thought and action were inspired by both Indian and Western traditions. And, of course, in that his influence has spread across the globe. He was shaped by his upbringing in Gujarat India and the influences of Hindu and Jain piety. He identified as a Sanatani Hindu. Yet he was also influenced by Western thought: the New Testament, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, Count Leo Tolstoy. We will read these authors: Thoreau, On Civil Disobedience; Ruskin, Unto This Last; Tolstoy, A Letter to a Hindu and The Kingdom of God is Within You. We will read Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, and a variety of texts from his Collected Works covering the social, political, and religious dimensions of his struggle for a free India and an India of social justice. We will read selections from his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the book that was his daily inspiration and that also, ironically, was the inspiration of his assassin. We will encounter Gandhi’s clash over communal politics and caste with another architect of modern India – Bimrao Ambedkar, author of the constitution, Buddhist convert, and leader of the “untouchable” community. -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

1. Letter to Children of Bal Mandir

1. LETTER TO CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR KARACHI, February 4, 1929 CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR, The children of the Bal Mandir1are too mischievous. What kind of mischief was this that led to Hari breaking his arm? Shouldn’t there be some limit to playing pranks? Let each child give his or her reply. QUESTION TWO: Does any child still eat spices? Will those who eat them stop doing so? Those of you who have given up spices, do you feel tempted to eat them? If so, why do you feel that way? QUESTION THREE: Does any of you now make noise in the class or the kitchen? Remember that all of you have promised me that you will make no noise. In Karachi it is not so cold as they tried to frighten me by saying it would be. I am writing this letter at 4 o’clock. The post is cleared early. Reading by mistake four instead of three, I got up at three. I didn’t then feel inclined to sleep for one hour. As a result, I had one hour more for writing letters to the Udyoga Mandir2. How nice ! Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 9222 1 An infant school in the Sabarmati Ashram 2 Since the new constitution published on June 14, 1928 the Ashram was renamed Udyoga Mandir. VOL.45: 4 FEBRUARY, 1929 - 11 MAY, 1929 1 2. LETTER TO ASHRAM WOMEN KARACHI, February 4, 1929 SISTERS, I hope your classes are working regularly. I believe that no better arrangements could have been made than what has come about without any special planning. -

Kasturba Gandhi an Embodiment of Empowerment

Kasturba Gandhi An Embodiment of Empowerment Siby K. Joseph Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai 2 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong. First Published February 2020 Reprint March 2020 © Author Published by Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai Mani Bhavan, 1st Floor, 19 Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007, MS, India. Website :https://www.gsnmumbai.org Printed at Om Laser Printers, 2324, Hudson Lines Kingsway Camp – 110 009 Siby K. Joseph 3 CONTENTS Foreword Raksha Mehta 5 Preface Siby K. Joseph 7-12 1. Early Life 13-15 2. Kastur- The Wife of Mohandas 16-24 3. In South Africa 25-29 4. Life in Beach Grove Villa 30-35 5. Reunion 36-41 6. Phoenix Settlement 42-52 7. Tolstoy Farm 53-57 8. Invalidation of Indian Marriage 58-64 9. Between Life and Death 65-72 10. Back in India 73-76 11. Champaran 77-80 12. Gandhi on Death’s door 81-85 13. Sarladevi 86-90 14. Aftermath of Non-Cooperation 91-94 15. Borsad Satyagraha and Gandhi’s Operation 95-98 16. Communal Harmony 99-101 4 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. 17. Salt Satyagraha 102-105 18. Second Civil Disobedience Movement 106-108 19. Communal Award and Harijan Uplift 109-114 20. -

Quiz 1. What Is the Full Name of Mahatma Gandhi? Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Answers for Gandhi Jayanthi Day - Quiz 1. What is the full name of Mahatma Gandhi? Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 2. Where was Gandhiji pushed off a train? Pietermaritzburg 3. Who gave the title Mahatma to Mr. Gandhi? Rabindranath Tagore 4. What is the Tamil version of Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography? Sathya sothanai 5. Where did the attire change of Mahatma Gandhi take place? Madurai 6. What is the message he gave to the World? Satyagraha or Non-violence 7. Who was the political guru of Mahatma Gandhi? Gopal Krishna Gokhale 8. At which place was Gandhiji arrested for the first time by the British Government for sedition? Ahmedabad 9. This march was launched by the Mahatma Gandhi in March 1930 to produce what? Salt 10. When was the Mahatma Gandhi - Irwin Pact signed? March 5, 1931. 11. When did Mahatma Gandhi given the slogan ‘Do or Die’? Quit India movement. 12. Which book did Gandhiji translate into the Gujarati language? “Unto This Last” by John Ruskin. 13. Gandhiji confessed his guilt of stealing for what purpose? Smoking. 14. Although he had the support of Gandhiji, he lost the presidential election of Congress against Bose. Who is he? Pattabhi Sitaramayya 15. Which is the weekly run by Gandhiji? Harijan 16. Congress President said “never before was so great an event consummated with such little bloodshed and violence.” Who was he? J B Kripalani 17. Motilal Nehru said “Like the historic march of Ramchandra to Lanka, the march of Gandhi will be memorable”. What march is that? Dandi march 18. At which place did he undertake his last fast on January 13, 1948? Delhi 19. -

GANDHIJI in SOUTH AFRICA Reminiscences of His Contemporaries

1 GANDHIJI IN SOUTH AFRICA Reminiscences of his Contemporaries Compiled by: E. S. Reddy [NOTE: This compilation consists of selected articles and short passages in books. For additional information, please see appendix.] 2 CONTENTS ANDREWS, C. F. “The Tribute of a Friend” (in Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., Mahatma Gandhi: Essays and Reflections on His Life and Work. Fourth edition. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1977. Originally published in 1939.) CATT, Mrs. Carie Chapman “Gandhi and South Africa” (in The Woman Citizen, March 1922) CURTIS, Lionel “Two meetings with Gandhi” (in Radhakrishnan, op. cit.) DESAI, Pragji “Satyagraha in South Africa” (in Chandrashanker Shukla, ed., Reminiscences of Gandhiji by Forty-eight Contributors. Bombay: Vora & Co., 1951.) GANDHI, Manilal “Memories of Gandhiji” (in Indian Review, Madras, March 1952) KRAUSE, F.E.T. “Gandhiji in South Africa” (in Shukla, op. cit.) LAWRENCE, Vincent “Sixty Years Memoir” (extract) MEHTA, P.J. “M.K. Gandhi and the South African Indian Problem” (in Indian Review, Madras, May 1911) PHILLIPS, Agnes M. “Recollections” (in Shukla, op. cit.) POLAK, H.S.L. “South African Reminiscences” (in Indian Review, Madras, February, March and May 1925) “A South African Reminiscence” (in Indian Review, October 1926) “Memories of Gandhi” (in Contemporary Review, London, March 1948) “Some South African Reminiscences” (in Chandrashanker Shukla, ed., Incidents of Gandhiji’s Life, by Fifty-four Contributors. Bombay: Vora & Co., 1949.) 3 POLAK, Mrs. Millie Graham “In the South African Days” (in Shukla, Incidents of Gandhiji’s Life.) “My South African Days with Gandhi” (in Indian Review, October 1964) POLAK, H.S.L. AND Mrs. Millie Graham “Gandhi, the Man” (in Indian Review, October 1929) SMUTS, J.C. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Selfsame Spaces: Gandhi, Architecture and Allusions in Twentieth Century India. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Venugopal Maddipati IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Catherine Asher, Adviser May, 2011 @ Venugopal Maddipati 2011 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following institutions and people for supporting my work. I am grateful to the American Institute of Indian Studies in Delhi, The Center of Science for Villages in Wardha and Kumarappapuram, The Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research in Mumbai, The Gandhi Memorial Library in Delhi, The Center for Developmental Studies in Trivandrum, The Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyaan and the University of Minnesota. I would like to thank the following individuals: Bindia Thapar, Purnima Mehta, Bindu Rajasenan, Soman Nair, Tilak Baker, Laurie Baker, Varsha Kaley, Vibha Gupta, Sameer Kuruve, David Faust, Donal Johnson, Eleanor Zelliot, Jane Blocker, Ajay Skaria, Anna Clark, Sarah Sik, Lynsi Spaulding, Riyaz Latif, Radha Dalal, Aditi Chandra, Sugata Ray, Atreyee Gupta, Midori Green, Sinem Arcak, Sherry, Dick, Jodi, Paul Wilson, Madhav Raman, Dhruv Sud, my parents, my sister Sushama, my mentors and my beloved Gurus, Frederick Asher and Catherine Asher. i Dedication Dedicated to my Tatagaru, Surapaneni Venugopal Rao. Tatagaru, if you can read this: You brought me up and taught me how to go beyond myself. ii Abstract In this dissertation, I suggest that the Indian political leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi infused deep and enigmatic meanings into everyday physical objects, particularly buildings. Indeed, the manner in which Gandhi named the buildings in his famous Satyagraha Ashram in Ahmedabad in the early part of the twentieth century, makes it somewhat difficult to write, in isolation, about their physical appearance. -

Mahatma Gandhi's Message for Us in the 21St Century

MAHATMA GANDHI’S MESSAGE FOR US IN THE 21ST CENTURY Christian Bartolf* Dominique Miething** Abstract Commemorating Mahatma Gandhi, 150 years after his birthday on 2nd October, 1869, we (Gandhi Information Center,Berlin, Germany ) will publish four basic essays on his nonviolent resistance in South Africa, the “Origin of Satyagraha: Emancipation from Slavery and War” – a German- Indian collaboration. Here we share with you the abstracts of these four essays:1) Thoreau – Tolstoy – Gandhi: The Origin of Satyagraha, 2) Socrates – Ruskin – Gandhi: Paradise of Conscience, 3) Garrison – Thoreau – Gandhi: Transcending Borders, 4) Gandhi – Kallenbach – Naidoo: Emancipation from the colonialist and racist system. Key words: Commemorating Mahatma Gandhi, essays on nonviolent resistance, Origin of Satyagraha Introduction Satyagraha (firmness in truth) and sarvodaya (welfare of all) are the core political concepts of Mahatma Gandhi’s political philosophy. Sarvodaya (“welfare for all”), a Sanskrit term meaning “universal uplift”, was used by Mahatma Gandhi as the title of his 1908 translation of John Ruskin’s tract on political economy “Unto This Last” (“the object which the book works towards is the welfare of all - that is, the advancement of all and not merely of the greatest number”, May 16, 1908). Vinoba Bhave followed this path in his exemplary reform movements. Satyagraha became the alternative nonviolent resistance soul force of the oppressed against injustice, an alternative to war and guerilla war and civil war, and yes: genocide. The term Satyagraha– as Gujarati equivalent of “passive resistance” - was coined aftera competition in the journal “Indian Opinion” in South Africa in 1908, the time period when genocidal massacres in colonial Africa were ongoing – in German South-West Africa * Educational and Political Scientist, President of the Gandhi Information Center. -

Ruskin-Until This Last

For more texts of enduring interest, visit the QuikScan Library at http://quikscan.org/library/index.html Welcome to this QuikScan edition of Unto This Last by John Ruskin Four essays on economics and social justice published in 1860 John Ruskin (1819-1900) was one of the most remarkable voices of Victorian England. Having achieved acclaim as an art critic, Ruskin changed directions and by writing Unto This Last angered England's mercantile classes by fiercely condemning their greed and the poverty he saw everywhere around him. He challenged the dehumanized economic thinking of his day and urged a new kind of economics based on social justice. Ruskin became an embattled champion of the working class. While gradually succumbing to despair and insanity, he proposed a wide range of progressive social reforms and founded a utopian community, St. George's Guild, to put those ideas into practice. Many of Ruskin's ideas have now gained wide acceptance. Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and the British Socialist movement were deeply influenced by Ruskin. Because Ruskin condemned the pollution of air, water, and soil caused by uncontrolled industrialism, he is regarded as one of the very first environmentalists. Why a QuikScan edition? Ruskin is a brilliant writer with a very lively prose style. Even so, Unto This Last, while brief, challenges even well-educated and motivated readers. QuikScan is unique because it provides brief summaries throughout the book, making it much easier to understand and dramatically increasing retention. And, if a section of the book doesn't interest you, read just the summary and keep going. -

Unto This Last a Paraphrase

Unto This Last A Paraphrase * by M. K. Gandhi Unto This Last by John Ruskin was first published in 1860 as a series of articles in Cornhill Magazine. In 1908 Gandhi serialized a nine-part paraphrase of Ruskin’s book into Gujarati in Indian Opinion and later published it as a pamphlet under the title Sarvodaya (The Welfare of All). Valji Govind Desai retranslated Gandhi’s paraphrase into English in 1951 under the title Unto This Last: A Paraphrase. It was revised in 1956. The 1956 text is re-issued here. © The Navajivan Trust Translator’s Note In a chapter in his Autobiography (Part IV, Chapter XVIII) entitled ‘The Magic Spell of a Book’ Gandhiji tells us how he read Ruskin’s Unto This Last on the twenty-four hours’ journey from Johannesburg to Durban. ‘The train reached there in the evening. I could not get any sleep that night. I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book.…I translated it later into Gujarati, entitling it Sarvodaya.’ Sarvodaya is here re-translated into English, Ruskin’s winged words being retained as far as possible. At the end of that chapter Gandhiji gives us a summary of the teach- ings of Unto This Last as he understood it: 1. The good of the individual is contained in the good of all. 2. A lawyer’s work has the same value as the barber’s, as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work. 3. A life of labour, i.e. the life of the tiller of the soil and the handi- craftsman is the life worth living. -

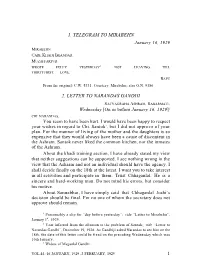

1. Telegram to Mirabehn 2. Letter to Narandas Gandhi

1. TELEGRAM TO MIRABEHN January 16, 1929 MIRABEHN CARE KHADI BHANDAR MUZAFFARPUR WROTE FULLY YESTERDAY1. NOT LEAVING TILL THIRTYFIRST. LOVE. BAPU From the original: C.W. 5331. Courtesy: Mirabehn; also G.N. 9386 2. LETTER TO NARANDAS GANDHI SATYAGRAHA ASHRAM, SABARMATI, Wednesday [On or before January 16, 1929]2 CHI. NARANDAS, You seem to have been hurt. I would have been happy to respect your wishes in regard to Chi. Santok3, but I did not approve of your plan. For the manner of living of the mother and the daughters is so expensive that they would always have been a cause of discontent in the Ashram. Santok never liked the common kitchen, nor the inmates of the Ashram. About the khadi training section, I have already stated my view that neither suggestions can be supported. I see nothing wrong in the view that the Ashram and not an individual should have the agency. I shall decide finally on the 18th at the latest. I want you to take interest in all activities and participate in them. Trust Chhaganlal. He is a sincere and hard-working man. Do not mind his errors, but consider his motive. About Sannabhai, I have simply said that Chhaganlal Joshi’s decision should be final. For no one of whom the secretary does not approve should remain. 1 Presumably a slip for “day before yesterday”; vide “Letter to Mirabehn”, January 14, 1929. 2 Year inferred from the allusion to the problem of Santok; vide “Letter to Narandas Gandhi”, December 19, 1928. As Gandhiji asked Narandas to see him on the 18th, the date of this letter could be fixed on the preceding Wednesday which was 16th January. -

Literary Vision of Symbolic India: Removing the Veil and Stepping Into Spiritual India

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 421 369 SO 027 999 AUTHOR Barry, Patricia TITLE Literary Vision of Symbolic India: Removing the Veil and Stepping into Spiritual India. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad 1996 (India). SPONS AGENCY United States Educational Foundation in India. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 116p.; Some materials may not photocopy well. For other documents in this 1996 program, see SO 028 000 SO 028 007. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Grade 6; *Indians; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Intermediate Grades; Literature; Middle Schools; *Multicultural Education; Religion Studies; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *India ABSTRACT This curriculum guide was developed to assist middle-school students in understanding the complexity of India. A slide presentation is used in combination with several activities for interdisciplinary study of India through literature and social studies. A comprehensive bibliography provides suggestions for further reading. Sections of the guide include: (1) Preface; (2) "Sacred India"; (3) "Hinduism"; (4) "Sadhus"; (5) "Buddhism"; (6) "Islam"; (7) "Sikhism"; (8) "Jainism"; (9) "Zoroastrianism"; (10) "Christianity and Judaism"; (11) "The Vedas and Upanishads"; (12)"The Ramayana"; (13) "The Mahabharata"; (14) "The Bhagavad Gita"; (15) "Music"; (16) "Dance"; (17) "The Mughals";(18) "Satin;(19)"The Ganges"; (20) "Nataraja"; (21) "Mahatma Gandhi"; (22) "The Bhagavad Gita and Henry David Thoreau";(23) "Rabindranath Tagore"; (24) "Dhobi Wallahs";(25) "Dhaba Lunches"; (26) "Indian Cuisine";(27) "Child Labor in India"; (28) "Private Schools in India"; (29) (30) "Rice";(31) "Climate";(32) "Floor Designs of India";(33) "Population"; and (34) "Recommended Reading-Bibliography." (EH) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document.