Boilermakers' and the Separation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Briefing Paper No 27/96 the Kable Case: Implications for New South Wales

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Briefing Paper No 27/96 The Kable Case: Implications for New South Wales by 0 Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Dr David Clune (9230 2484), Manager Ms Honor Figgis (9230 2768) Research Officer, Law Dr Gareth Griffith (9230 2356) Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government Ms Fiona Manning (9230 3085) Research Officer, Law/Social Issues Mr Stewart Smith (9230 2798) Research Officer, Environment Ms Marie Swain (9230 2003) Research Officer, Law Mr John Wilkinson (9230 2006) Research Officer, Economics ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7310 5969 7 © 1996 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. October 1996 Briefing Paper is published by the NSW Parliamentary Library CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 2 Background to the decision 4 3 The main issues in the case 5 4 Separation of powers and the States 6 5 The High Court's decision in Kahle 's case - the majority view 10 6 The High Court's decision in Kahle 's case - the minority view 16 7 The implications of Kable 's case for NSW 17 8 Conclusions 23 Appendix - Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge the helpful contributions of Professor George Winterton of the Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales. -

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

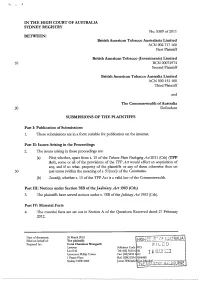

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A. -

Palmer-WA Pltf.Pdf

H I G H C O U R T O F A U S T R A L I A NOTICE OF FILING This document was filed electronically in the High Court of Australia on 23 Apr 2021 and has been accepted for filing under the High Court Rules 2004. Details of filing and important additional information are provided below. Details of Filing File Number: B52/2020 File Title: Palmer v. The State of Western Australia Registry: Brisbane Document filed: Form 27A - Appellant's submissions-Plaintiff's submissions - Revised annexure Filing party: Plaintiff Date filed: 23 Apr 2021 Important Information This Notice has been inserted as the cover page of the document which has been accepted for filing electronically. It is now taken to be part of that document for the purposes of the proceeding in the Court and contains important information for all parties to that proceeding. It must be included in the document served on each of those parties and whenever the document is reproduced for use by the Court. Plaintiff B52/2020 Page 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No B52 of 2020 BRISBANE REGISTRY BETWEEN: CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Plaintiff and STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 10 Defendant PLAINTIFF’S OUTLINE OF SUBMISSIONS Clive Frederick Palmer Date of this document: 23 April 2021 Level 17, 240 Queen Street T: 07 3832 2044 Brisbane Qld 4000 E: [email protected] Plaintiff Page 2 B52/2020 -1- PART I: FORM OF SUBMISSIONS 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART II: ISSUES PRESENTED 2. -

International Production Orders) Bill 2020 (The Bill), for the Committee’S Consideration

Table of Contents Overview of submission ................................................................................................................... 3 Advantages over existing crime cooperation arrangements .......................................................... 3 Issuing IPOs – accountable and independent decision making....................................................... 5 Persona designata functions ......................................................................................................... 5 IPOs for national security purposes ............................................................................................. 7 The establishment of an Australian Designated Authority (ADA) ................................................... 9 Safeguards – human rights and data protection/privacy .............................................................. 10 Death penalty safeguards ............................................................................................................ 10 Other safeguards ......................................................................................................................... 11 Data protection and privacy ...................................................................................................... 11 Evidentiary requirements .............................................................................................................. 13 Evidentiary certificates ............................................................................................................... -

Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012

Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the Military Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012 The purpose of this submission is to examine four key objections which have been raised to the establishment of a permanent military court in Australia in the form of the Military Court of Australia. The submission is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather seeks to consider some of the legal issues which arise in relation to these four objections.1 The authors do not consider that the first three objections are legitimate bases to reject the establishment of the Military Court of Australia, but are concerned that the fourth objection (the lack of jury trial) may give rise to a future constitutional challenge. The four objections to the establishment of a permanent military court which have been raised are as follows: 1. The establishment of a permanent court is unnecessary given that the current system is not defective This objection is based on the idea that if the system is not broken it does not need fixing. The current system of courts martial and Defence Force magistrates (reintroduced after the High Court struck down the Australian Military Court in Lane v Morrison2), has certainly survived a number of constitutional challenges in the High Court – although often with strong dissents. The strength of those dissents, the continued shifts of opinion within the High Court, and the absence of a clear and coherent consensus within that Court on the extent to which the specific constitutional powers relied upon by the Commonwealth3 can support a military justice system operating outside Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution, means that the validity of the current system is assumed rather than assured. -

Chapter One the Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case

Chapter One The Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case Professor Geoffrey de Q Walker Holding the balance: 1903 to 1920 The High Court of Australia’s 1920 decision in the Engineers’ Case1 remains an event of capital importance in Australian history. It is crucial not so much for what it actually decided as for the way in which it switched the entire enterprise of Australian federalism onto a diverging track, that carried it to destinations far removed from those intended by the generation that had brought the Federation into being. Holistic beginnings. How constitutional doctrine developed through the Court’s decisions from 1903 to 1920 has been fully described elsewhere, including in a paper presented at the 1995 conference of this society by John Nethercote.2 Briefly, the original Court comprised Chief Justice Griffith and Justices Barton and O’Connor, who had been leaders in the federation movement and authors of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution. The starting-point of their adjudicative philosophy was the nature of the Constitution as an enduring instrument of government, not merely a British statute: “The Constitution Act is not only an Act of the Imperial legislature, but it embodies a compact entered into between the six Australian colonies which formed the Commonwealth. This is recited in the Preamble to the Act itself”.3 Noting that before Federation the Colonies had almost unlimited powers,4 the Court declared that: “In considering the respective powers of the Commonwealth and the States it is essential to bear in mind that each is, within the ambit of its authority, a sovereign State”.5 The founders had considered Canada’s constitutional structure too centralist,6 and had deliberately chosen the more decentralized distribution of powers used in the Constitution of the United States. -

Murdoch University School of Law Michael Olds This Thesis Is

Murdoch University School of Law THE STREAM CANNOT RISE ABOVE ITS SOURCE: THE PRINCIPLE OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT INFORMING A LIMIT ON THE AMBIT OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH Michael Olds This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Laws with Honours at Murdoch University in 2016 Word Count: 19,329 (Excluding title page, declaration, copyright acknowledgment, abstract, acknowledgments and bibliography) DECLARATION This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other University. Further, to the best of my knowledge or belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. _______________ Michael Olds ii COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s 51(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: ………………………………… Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Laws with Honours Thesis Title: The stream cannot rise above its source: The principle of Responsible Government informing a limit on the ambit of the Executive Power of the Commonwealth Author: Michael Olds Year: 2016 iii ABSTRACT The Executive Power of the Commonwealth is shrouded in mystery. Although the scope of the legislative power of the Commonwealth Parliament has been settled for some time, the development of the Executive power has not followed suit. -

Judges and Retirement Ages

JUDGES AND RETIREMENT AGES ALYSIA B LACKHAM* All Commonwealth, state and territory judges in Australia are subject to mandatory retirement ages. While the 1977 referendum, which introduced judicial retirement ages for the Australian federal judiciary, commanded broad public support, this article argues that the aims of judicial retirement ages are no longer valid in a modern society. Judicial retirement ages may be causing undue expense to the public purse and depriving the judiciary of skilled adjudicators. They are also contrary to contemporary notions of age equality. Therefore, demographic change warrants a reconsideration of s 72 of the Constitution and other statutes setting judicial retirement ages. This article sets out three alternatives to the current system of judicial retirement ages. It concludes that the best option is to remove age-based limitations on judicial tenure. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 739 II Judicial Retirement Ages in Australia ................................................................... 740 A Federal Judiciary .......................................................................................... 740 B Australian States and Territories ............................................................... 745 III Criticism of Judicial Retirement Ages ................................................................... 752 A Critiques of Arguments in Favour of Retirement Ages ........................ -

Judicial Conduct: Crafting a System That Enhances Institutional Integrity

JUDICIAL CONDUCT: CRAFTING A SYSTEM THAT ENHANCES INSTITUTIONAL INTEGRITY GABRIELLE APPLEBY* AND SUZANNE LE M IRE† Judges are human. It is their humanity that allows them to pass judgement on the complexities of fact and law in cases before them. However, their humanity also means they are subject to the usual gamut of human frailties. Problematic judicial conduct remains rare in Australia. However, failing to acknowledge and address it has the potential to damage the integrity of the courts and undermine the ability of individual judges to fulfil the judicial function. In this article we examine the requirements for a ‘good’ complaints system through a comparative analysis of systems operating in Australia and overseas. We proffer an alternative system for Australia, tailored to fit within our constitutional constraints whilst promoting the institutional integrity of the judiciary. CONTENTS I Introduction ................................................................................................................... 2 II Judicial Misconduct and Incapacity: Scope and Categories ................................... 5 A Incapacity .......................................................................................................... 9 B Misconduct and Misbehaviour .................................................................... 12 1 Prior to Taking Judicial Office ......................................................... 12 2 During Judicial Office — On the Bench ........................................ 12 * LLB (Hons) (UQ), LLM -

Jurisdiction, Granted Special Leave to Appeal, Refused Special Leave to Appeal and Not Proceeding Or Vacated

HIGH COURT BULLETIN Produced by the Legal Research Officer, High Court of Australia Library [2012] HCAB 08 (24 August 2012) A record of recent High Court of Australia cases: decided, reserved for judgment, awaiting hearing in the Court's original jurisdiction, granted special leave to appeal, refused special leave to appeal and not proceeding or vacated 1: Cases Handed Down ..................................... 3 2: Cases Reserved ............................................ 8 3: Original Jurisdiction .................................... 30 4: Special Leave Granted ................................. 32 5: Cases Not Proceeding or Vacated .................. 40 6: Special Leave Refused ................................. 41 SUMMARY OF NEW ENTRIES 1: Cases Handed Down Case Title Public Service Association of South Australia Administrative Law Incorporated v Industrial Relations Commission of South Australia & Anor J T International SA v Commonwealth of Constitutional Law Australia; British American Tobacco Australasia Limited & Ors v Commonwealth of Australia – Orders Only RCB as Litigation Guardian of EKV, CEV, CIV Constitutional Law and LRV v The Honourable Justice Colin James Forrest, One of the Judges of the Family Court of Australia & Ors – Orders Only Baker v The Queen Criminal Law Douglass v The Queen – Orders Only Criminal Law Patel v The Queen Criminal Law The Queen v Khazaal Criminal Law Minister for Home Affairs of the Commonwealth Extradition & Ors v Zentai & Ors [2012] HCAB 08 1 24 August 2012 Summary of New Entries Sweeney (BHNF -

'Executive Power' Issue of the UWA Law Review

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA LAW REVIEW Volume 43(2) March 2018 EXECUTIVE POWER ISSUE Introduction Dr Murray Wesson ............................................................................................................. 1 Executive Power in Australia - Nurtured and Bound in Anxiety The Hon Robert French AC ............................................................................................ 16 The Strange Death of Prerogative in England Thomas Poole .................................................................................................................... 42 Judicial Review of Non-Statutory Executive Action: Australia and the United Kingdom Amanda Sapienza .............................................................................................................. 67 Section 61 of the Commonwealth Constitution and an 'Historical Constitutional Approach': An Excursus on Justice Gageler's Reasoning in the M68 Case Peter Gerangelos ............................................................................................................. 103 Nationhood and Section 61 of the Constitution Dr Peta Stephenson ........................................................................................................ 149 Finding the Streams' True Sources: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication and Executive Power Joshua Forrester, Lorraine Finlay and Augusto Zimmerman .................................. 188 A Comment on How the Implied Freedom of Political Communication Restricts Non-Statutory Executive Power -

Constitutionally Protected Due Process and the Use of Criminal Intelligence Provisions 125

2014 Constitutionally Protected Due Process and the Use of Criminal Intelligence Provisions 125 CONSTITUTIONALLY PROTECTED DUE PROCESS AND THE USE OF CRIMINAL INTELLIGENCE PROVISIONS ANTHONY GRAY * I INTRODUCTION Demands for government response to perceived threats to national security and personal safety, government incentives to appear ‘tough on crime’ and the absence of an express bill of rights have combined to fuel ever-increasing government intrusions on fundamental rights and liberties that were once thought to be beyond reproach. Recent examples in the Australian context have included property confiscation laws, in the absence of a specific allegation or finding of guilt, reverse onus provisions, curtailment of the right to silence, criminalisation of mere acts of association, and executive detention of individuals. A current area of controversy is the use of ‘closed court’ processes in particular cases, aligned with the adoption of a court process whereby the person affected by the proceeding may lose the opportunity to see or hear the evidence being led against them, and with that the opportunity to cross-examine the witnesses being used. These types of laws offend several fundamental rights, but are claimed by governments to be necessary to protect witnesses and secure important evidence. For ease of reference, and because this is the phrasing used by the relevant legislation in Australia, I will refer to these as ‘criminal intelligence provisions’. This type of legislation raises broader questions, specifically the extent to which a ‘due process’ principle may be derived from Chapter III of the Constitution (‘Chapter III’), and the extent to which such a principle might be engaged to preserve and protect fundamental human rights, such as those affected by ‘criminal intelligence’ type provisions.