Shanks Full Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

2020-2021 Newsletter Department of Art History the Graduate Center, Cuny

2020-2021 NEWSLETTER DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY THE GRADUATE CENTER, CUNY 1 LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE OFFICER Dear GC Art History Community, The 2020-21 academic year has been, well, challenging for all of us at the GC, as I imagine it has for you. The building—boarded up in November for the elections—is still largely off-limits to students and faculty; the library is closed; classes and meetings have been almost exclusively virtual; and beyond the GC, many of us have lost friends, family, or jobs due to the pandemic and its repercussions. Through it all, we have struggled to keep our community together and to support one another. I have been extraordinarily impressed by how well students, faculty, and staff in the program have coped, given the circumstances, and am I hopeful for the future. This spring, we will hold our rst in-person events—an end-of-year party and a graduation ceremony for 2020 and 2021 Ph.D.s, both in Central Park—and look forward to a better, less remote fall. I myself am particularly looking forward to fall, as I am stepping down as EO and taking a sabbatical. I am grateful to all of you for your help, advice, and patience over the years, and hope you will join me in welcoming my successor, Professor Jennifer Ball. Before getting too excited about the future, though, a few notes on the past year. In fall 2020, we welcomed a brave, tough cohort of ten students into the Ph.D. Program. They have forged tight bonds through coursework and a group chat (not sure if that's the right terminology; anyway, it's something they do on their phones). -

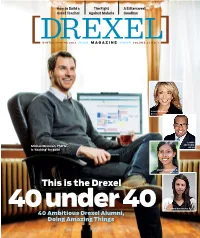

This Is the Drexel

How to Build a The Fight A Bittersweet Great Teacher Against Malaria Goodbye [DREXELWINTER/SPRING 2013 /////// MAGAZINE //////// VOLUME 23 NO. 1 ] COLLEEN WOLFE, BA’08 AJAMU JOHNSON, Michael Brennan, PhD’12, BS’02 is ‘hacking’ for good AMRITA BHOWMICK, MPH’10 This is the Drexel 40 under 40 DREW GINSBURG, BS’09 40 Ambitious Drexel Alumni, Doing Amazing Things 117 Total number of years that Drexel has competed in athletics. And each of those years is now covered in detail at the new Janet E. and Barry C. Burkholder Athletics Hall of Fame, which opened with a gala event at the Daskalakis Athletic Center in early December. The new Hall of Fame is an interactive exhibit that allows visitors to view a complete history of Drexel Athletics, including information on Drexel greats, retired numbers, memorable moments, all- time rosters and more (see story, Page 21). THE LEDGER [ A NUMERICAL ANALYSIS OF LIFE AT DREXEL ] Number of MacBooks held by the new laptop kiosk at the W.W. Hagerty 12 Library—a kiosk that allows students to check out one of 12 MacBooks for free, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Drexel is the third university in the nation to install this kind of kiosk, and it’s possible that additional machines could be installed around campus in the future. Said Drexel Libraries Dean Danuta A. Nitecki: “This was a great opportunity to match a specific student need with library staff’s ongoing exploration of cutting-edge technologies.” Total raised so far by the College of Medicine’s annual Pediatric AIDS Benefit Concert (PABC). -

High Performance Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p30369v Online items available Finding aid for the magazine records, 1953-2005 Finding aid for the magazine 2006.M.8 1 records, 1953-2005 Descriptive Summary Title: High Performance magazine records Date (inclusive): 1953-2005 Number: 2006.M.8 Creator/Collector: High Performance Physical Description: 216.1 Linear Feet(318 boxes, 29 flatfile folders, 1 roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: High Performance magazine records document the publication's content, editorial process and administrative history during its quarterly run from 1978-1997. Founded as a magazine covering performance art, the publication gradually shifted editorial focus first to include all new and experimental art, and then to activism and community-based art. Due to its extensive compilation of artist files, the archive provides comprehensive documentation of the progressive art world from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Linda Burnham, a public relations officer at University of California, Irvine, borrowed $2,000 from the university credit union in 1977, and in a move she described as "impulsive," started High -

Myths to Live By: Uncovering the Veiled Past of Actress/Artist Minnie Ashley by Roy Collins William A

Myths to Live By: Uncovering the Veiled Past of Actress/Artist Minnie Ashley by Roy Collins William A. Chanler, Editor On or about June 16th, 1845, 17-year-old Bridget Lyons set sail by ferry from County Cork, Ireland to Liverpool, England. From Liverpool she gained passage aboard the packet ship Concordia, bound for Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. The year 1845 marked the beginning of the ill-fated Potato Famine in Ireland, a dark period that would last six years. It brought mass starvation, poverty, and a multitude of deaths across the island. During the famine period, it was typical for Irish families to send their able-bodied children to seek opportunity in Europe and across the Atlantic to North America. The exact location of the residence where Bridget had resided in County Cork remains uncertain. We know only Photo circa 1898 by Benjamin Falk that later in life Bridget Lyons (then Bridget Tully) would marry John Campbell in Fall River, Massachusetts in 1861. On that marriage record her father was listed as William Lyon and her mother as Catherine (Curly) Lyon. The letter “S” at the end of the surname may have been dropped when transcribed by the town clerk as it was the only time the surname was spelled without the “S.” Most emigres traveled to the United States and Canada on the well-established Mc Corkell Line which offered sea-worthy sailing ships equipped to haul both passengers and freight. Depending upon the fare paid for passage, emigres had the choice of either a small cabin or state room, comparable in size to a small hotel room. -

Survival Research Laboratories: a Dystopian Industrial Performance Art

arts Article Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art Nicolas Ballet ED441 Histoire de l’art, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Galerie Colbert, 2 rue Vivienne, 75002 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 29 January 2019 Abstract: This paper examines the leading role played by the American mechanical performance group Survival Research Laboratories (SRL) within the field of machine art during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and as organized under the headings of (a) destruction/survival; (b) the cyborg as a symbol of human/machine interpenetration; and (c) biomechanical sexuality. As a manifestation of the era’s “industrial” culture, moreover, the work of SRL artists Mark Pauline and Eric Werner was often conceived in collaboration with industrial musicians like Monte Cazazza and Graeme Revell, and all of whom shared a common interest in the same influences. One such influence was the novel Crash by English author J. G. Ballard, and which in turn revealed the ultimate direction in which all of these artists sensed society to be heading: towards a world in which sex itself has fallen under the mechanical demiurge. Keywords: biomechanical sexuality; contemporary art; destruction art; industrial music; industrial culture; J. G. Ballard; machine art; mechanical performance; Survival Research Laboratories; SRL 1. Introduction If the apparent excesses of Dada have now been recognized as a life-affirming response to the horrors of the First World War, it should never be forgotten that society of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s was laboring under another ominous shadow, and one that was profoundly technological in nature: the threat of nuclear annihilation. -

Survival Research Laboratories Featured in the Art Newspaper

r THE ART NEWSPAPER The Robot wars: Mark Pauline and Survival Research Laboratories The Bay Area artist and his team build massive machines that act in dangerous performances—and they are opening their first gallery show in New York HELEN STOILAS 5th January 2018 17:11 GMT Mark Pauline and the Running Machine (1992) Courtesy of Survival Research Laboratories For four decades, Mark Pauline has turned robotics into a performance art. In 1978, the Bay Area artist started Survival Research Laboratories (SRL), a collaborative project with the stated purpose of “re-directing the techniques, tools, and tenets of industry, science, and the military away from their typical manifestations in practicality, product or warfare”. Since then, Pauline and a team of “creative technicians” have been building an army of massive machines—the giant articulated Spine Robot that gingerly picks up objects with its mechanised arm, the dangerously powerful Pitching Machine that can hurl a 2 x 4 at 200mph, and of course Mr Satan, a blast furnace with a human face that shoots flames from its eyes and mouth. These are used in performances that inspire equal parts awe, excitement and fear. Pauline and the SRL team are in New York this week for their first major gallery show at Marlborough Contemporary, Fantasies of Negative Acceleration Characterized by Sacrifices of a Non-Consensual Nature, opening on Saturday 5 January, with performances starting at 4pm. We spoke to the artist from his studio in Petaluma. The Art Newspaper: These machines are meant to have their own life, they’re independent actors in a way? Mark Pauline: Actually, they’re just meant to replace human performers in the events that we stage. -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27

Oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Lacy on March 16, 1990. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview has been extensively edited for clarification by the artist, resulting in a document that departs significantly from the tape recording, but that results in a far more usable document than the original transcript. —Ed. Interview [ Tape 1, side A (30-minute tape sides)] MOIRA ROTH: March 16, 1990, Suzanne Lacy, interviewed by Moira Roth, Berkeley, California, for the Archives of American Art. Could we begin with your birth in Fresno? SUZANNE LACY: We could, except I wasn’t born in Fresno. [laughs] I was born in Wasco, California. Wasco is a farming community near Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley. There were about six thousand people in town. I was born in 1945 at the close of the war. My father [Larry Lacy—SL], who was in the military, came home about nine months after I was born. My brother was born two years after, and then fifteen years later I had a sister— one of those “accidental” midlife births. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson -

Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence

Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence A COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROJECT A Window Between Worlds with Kim Abeles Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence A COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROJECT A Window Between Worlds with Kim Abeles Edited by Suvan Geer and Sandra Mueller Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence A Community Engagement Project A Window Between Worlds and Kim Abeles Catalogue printed on the occasion of the exhibition: Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence An Exhibition & Installation by artist Kim Abeles Presented by A Window Between Worlds in partnership with the Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles. March 1 – March 31, 2011 Korean Cultural Center Art Gallery Los Angeles, California Published in Los Angeles, California Editors: Suvan Geer and Sandra Mueller by A Window Between Worlds. Copy Editor: Laurence Jay Cover Art Photography: Ken Marchionno Copyright © 2011 by AWBW. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form Catalogue Design: Anne Gauldin, Gauldin/Farrington Design, Los Angeles, CA or by an electronic or mechanical means without prior Printer: Fundcraft Publishing Collierville, TN permission in writing from the publisher. Contributors retain copyright on writings and artworks presented Printed in the U.S.A. in this catalogue. This project is supported, in part, by grants from The James Irvine Foundation, the Contact [email protected]. Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles, the Durfee Foundation, the Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Target and the Women’s Foundation of California. Library of Congress CIP Data: 2011901555 ISBN: 978-0-578-07833-5 Cover Art & Handbook For Living Photography: Ken Marchionno Project Photography: Kim Abeles, Rose Curtis, Lynn Fischer, Ken Marchionno, Sandra Mueller, Nathalie Sanchez, Aaron Pipkin Tamayo Essay Photo Credits: Michael Haight courtesy of Laguna Art Museum (Suvan Geer), Suzanne Lacy and Rob Blalack (Suzanne Lacy), Lisa Finn and Cal Sparks (Barbara T. -

Sexual Violence in America: Theory, Literature, Activism

Sexual Violence in America: Theory, Literature, Activism ENGL | GNSE 18700 Winter 2019 Monday/Wednesday 4:30-5:50pm Cobb 303 Michael Dango, Ph.D. [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 2:30-4:30pm Walker 420 Course Description This course will consider how a spectrum of sexual violence has been represented, politicized, and theorized in the United States from the 1970s to the present. To get a handle on this vast topic, our archive will be wide-ranging, including legal statutes and court opinions on sexual harassment and pornography; fiction, poetry, and graphic novels that explore the limits of representing sexual trauma; activist discourses in pamphlets and editorials from INCITE to #MeToo; and ground- breaking essays by feminist and queer theorists, especially from critical women of color. How does the meaning of sex and of power shift with different kinds of representation, theory, and activism? How have people developed a language to share experiences of violation and disrupt existing power structures? And how do people begin to imagine and build a different world whether through fiction, law, or institutions? Because of the focus of this course, our readings will almost always present sexual violence itself in explicit and sometimes graphic ways. Much of the material can be upsetting. So, too, may be our class discussions, because difficult material can produce conversations whose trajectories are not knowable in advance. Careful attention to the material and to each other as we participate in the co-creation of knowledge will be our rule. However, even this cannot make a guarantee against surprises. Please read through all of the syllabus now so you know what lies ahead. -

Circa 125 Contemporary Visual Culture in Ireland Autumn 2008 | ¤7.50 £5 Us$12 | Issn 0263-9475

CIRCA 125 CONTEMPORARY VISUAL CULTURE IN IRELAND AUTUMN 2008 | ¤7.50 £5 US$12 | ISSN 0263-9475 c . ISSN 0263-9475 Contemporary visual culture in circa Ireland ____________________________ ____________________________ 2 Editor Subscriptions Peter FitzGerald For our subscription rates please see bookmark, or visit Administration/ Advertising www.recirca.com where you can Barbara Knezevic subscribe online. ____________________________ Board Circa is concerned with visual Graham Gosling (Chair), Mark culture. We welcome comment, Garry, Georgina Jackson, Isabel proposals and written Nolan, John Nolan, Hugh contributions. Please contact Mulholland, Brian Redmond the editor for more details, or consult our website ____________________________ www.recirca.com Opinions Contributing editors expressed in this magazine Brian Kennedy, Luke Gibbons are those of the authors, not ____________________________ necessarily those of the Board. Assistants Circa is an equal-opportunities Gemma Carroll, Sarah O’Brien, employer. Copyright © Circa Madeline Meehan, Kasia Murphy, 2008 Amanda Dyson, Simone Crowley ____________________________ ____________________________ Contacts Designed/produced by Circa Peter Maybury 43 / 44 Temple Bar www.softsleeper.com Dublin 2 Ireland Printed by W & G Baird Ltd, tel / fax (+353 1) 679 7388 Belfast [email protected] www.recirca.com Printed on 115gsm + 250gsm Arctic the Matt ____________________________ ____________________________ c ____________________________ ____________________________ CIRCA 125 AUTUMN 2008 3 Editorial 26 | Letters 28 | Update 30 | Features 32 | Reviews 66 | Project 107 | (front cover) Ben Craig degree-show installation 2008 courtesy the artist Culture night 2008 c . Circa video screening Circa screens the selected videos from the open submission Curated by Lee Welch, artist and co-director of Four Gallery, Dublin, videos will be shown in the Atrium of Temple Bar Gallery and Studios, Dublin on 19 September 2008.