Theorizing Athletic Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Binge-Reviews? the Shifting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Communication & Theatre Arts Publications 2016 Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism Myles McNutt Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Publishing Commons Repository Citation McNutt, Myles, "Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism" (2016). Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications. 15. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs/15 Original Publication Citation McNutt, M. (2016). Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism. Film Criticism, 40(1), 1-4. doi: 10.3998/fc.13761232.0040.120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication & Theatre Arts at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FILM CRITICISM Binge-Reviews? The Shifting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism Myles McNutt Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information) Volume 40, Issue 1, January 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/fc.13761232.0040.120 Permissions When should television criticism happen? The answer used to be pretty simple for critics: reviews were published before a series premiered, with daily or -

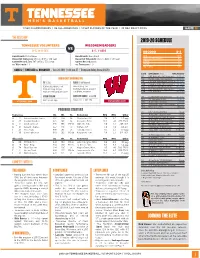

2019-20 Schedule Joining the Elite

TENNESSEE BASKETBALL MEN’S BASKETBALL 11 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS | 26 ALL-AMERICANS | 13 SEC PLAYERS OF THE YEAR | 49 NBA DRAFT PICKS GAME 12 THE MATCHUP 2019-20 SCHEDULE TENNESSEE VOLUNTEERS WISCONSIN BADGERS vs 8-3, 0-0 SEC 6-5, 1-1 B1G RECORD 8-3 Head Coach: Rick Barnes Head Coach: Greg Gard SEC 0-0 Record at Tennessee: 96-53 (.644) / 5th year Record at Wisconsin: 93-57 (.620) / 5th year NON-CONFERENCE 8-3 Career Record: 700-367 (.656) / 33rd year Career Record: Same HOME 6-1 vs. Wisconsin: 1-4 vs. Tennessee: 1-0 AWAY 0-1 NEUTRAL 2-1 GAME 12 | TENNESSEE vs. WISCONSIN - Dec. 28, 2019 | 1:36 p.m. ET | Thompson-Boling Arena (21,678) DATE OPPONENT (TV) TIME/RESULT N5 UNC Asheville (SEC Network+) W, 78-63 BROADCAST INFORMATION N12 Murray State (SEC Network) W, 82-63 CBS Vol Network N16 1-vs. #20 Washington (ESPN+/TSN) W, 75-62 TV | RADIO | N20 Alabama State (SEC Network+) W, 76-41 Carter Blackburn, PxP Bob Kesling, PxP N25 Chattanooga (SEC Network) W, 58-46 Clark Kellogg, analyst Bert Bertelkamp, analyst N29 2-vs. Florida State (CBS Sports) L, 60-57 Giancarlo Gennarini, producer Tim Berry, engineer N30 2-vs. #20 VCU W, 72-69 VIDEO STREAM SATELLITE RADIO | SiriusXM D4 Florida A&M (SEC Network) W, 72-43 CBS Sports app Sirius: 137 | XM: 190 D14 #13 Memphis (ESPN) L, 51-47 UTSPORTS.COM UWBADGERS.COM D18 at Cincinnati (ESPN2) L, 78-66 D21 Jacksonville State (SEC Network+) W, 75-53 D28 Wisconsin (CBS) 1:36 p.m. -

Grantland Grantland

12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Grantland The NBA's E-League Now Playing: Bad Luck, Tragedy, and Travesty LeBron James Controls the Chessboard Home Features Blogs The Triangle Sports News, Analysis, and Commentary Hollywood Prospectus Pop Culture Contributors Bill Simmons Bill Barnwell Rembert Browne Zach Lowe Katie Baker Chris Ryan Mark Lisanti,ht Wesley Morris Andy Greenwald Brian Phillips Jonah Keri Steven Hyden,da Molly Lambert Andrew Sharp Alex Pappademas,gl Rafe Bartholomew Emily Yoshida www.grantland.com/blog/the-triangle/post/_/id/85159/kyle-korvers-big-night-and-the-day-on-the-ocean-that-made-it-possible 1/10 12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Sean McIndoe Amos Barshad Holly Anderson Charles P. Pierce David Jacoby Bryan Curtis Robert Mays Jay Caspian Kang,jw SEE ALL » Simmons Quarterly Podcasts Video Contact ESPN.com Jump To Navigation Resize Font: A- A+ NBA Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible By Charles Bethea on December 9, 2013 4:45 PM ET,ht www.grantland.com/blog/the-triangle/post/_/id/85159/kyle-korvers-big-night-and-the-day-on-the-ocean-that-made-it-possible 2/10 12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Scott Cunningham/NBAE/Getty Images ACT 1: LAST FRIDAY, AMONG THE KORVERS I'm sitting third row at the Hawks-Cavs game, flanked by two large, handsome Midwesterners. -

Full Version

Volume 11, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents ARTICLES Reexploring the Esports Approach of America’s Three Major Leagues Peter A. Carfagna.................................................. 115 The NCAA’s Agent Certification Program: A Critical and Legal Analysis Marc Edelman & Richard Karcher ..................................... 155 Well-Intentioned but Counterproductive: An Analysis of the NFLPA’s Financial Advisor Registration Program Ross N. Evans ..................................................... 183 A Win Win: College Athletes Get Paid for Their Names, Images, and Likenesses, and Colleges Maintain the Primacy of Academics Jayma Meyer and Andrew Zimbalist ................................... 247 Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law Student Journals Office, Harvard Law School 1585 Massachusetts Avenue, Suite 3039 Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-3146; [email protected] www.harvardjsel.com U.S. ISSN 2153-1323 The Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law is published semiannually by Harvard Law School students. Submissions: The Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law welcomes articles from professors, practitioners, and students of the sports and entertainment industries, as well as other related disciplines. Submissions should not exceed 25,000 words, including footnotes. All manuscripts should be submitted in English with both text and footnotes typed and double-spaced. Footnotes must conform with The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (20th ed.), and authors should be prepared to supply any cited sources upon request. All manu- scripts submitted become the property of the JSEL and will not be returned to the author. The JSEL strongly prefers electronic submissions through the ExpressO online submission system at http://www.law.bepress.com/expresso or the Scholastica online submission system at https://harvard-journal-sports-ent-law.scholasticahq.com. -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

'Race' for Equality

American Journalism, 26:2, 99-121 Copyright © 2009, American Journalism Historians Association A ‘Race’ for Equality: Print Media Coverage of the 1968 Olympic Protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos By Jason Peterson During the Summer Olympics in 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos made history. Although they won the gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 200-meter dash, their athletic accom- plishments were overshadowed by their silent protest during the medal ceremony. Images of Smith and Carlos each holding up a single, closed, gloved fist have become iconic reminders of the Civil Rights movement. What met the two men after their protest was criticism from the press, primarily sportswriters. This article examines media coverage of the protest and its aftermath, and looks at how reporters dealt with Smith’s and Carlos’s political and racial statement within the context of the overall coverage of the Olympic Games. n the night of October 16, 1968, at the Olympic Games in Mexico City, U.S. sprinter Tommie Smith set a world record for the 200-meter dash by finishing O 1 in 19.8 seconds. The gold medal winner celebrated in a joyous embrace of fellow Olympian, college team- Jason Peterson is an mate, and good friend, John Carlos, who won instructor of journalism the bronze medal. However, Smith and Carlos at Berry College and a had something other than athletic accolades or Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern the spoils of victory on their minds. In the same Mississippi, Box 299, year the Beatles topped the charts with the lyr- Rome, GA 30149. -

Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 Vs

CUSE.COM Christmas’ Season and Career Highs Points Season: 35 vs. Wake Forest Career: 35 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 FG Made S Y R A C U E Season: 13 vs. Wake Forest Career: 13 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 25 FG Attempted Season: 21 vs. Wake Forest Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 O R A N G E Senior 6-9 250 3-Point FGM Philadelphia, Pa. Season: 0 Career: 0 Academy of the New Church 3-Point FGA Season: 1 at North Carolina NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM Career: 1 at North Carolina, 2014-15 FT Made Ranks third in the ACC in scoring (17.5 ppg.), fourth in rebounding (9.1), fi fth in fi eld goal Season: 11 vs. Louisville percentage (.552), second in blocked shots (2.52), sixth in off ensive rebounds (3.13) and Career: 11 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 FT Attempted fi fth defensive rebounds (5.97). Season: 13 vs. Louisville Nominated for the 2015 Allstate NABC and WBCA Good Works Teams. Career: 13 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 Finalist for the Wooden Award. Rebounds Season: 16 vs. Hampton Finalist for the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award. Career: 16 vs. Hampton, 2014-15 Finalist for the Robertson Trophy. Off. Rebounds Named to Lute Olson Award Watch List. Season: 6 vs. Kennesaw State, Hampton, St. John’s, Long Beach State, at Duke Named to Naismith Award Midseason Top 30. Career: 8 vs. Boston College, 2013-14 Earned ACSMA Most Improved Player Award and was named to ACSMA All-ACC First Team Def. -

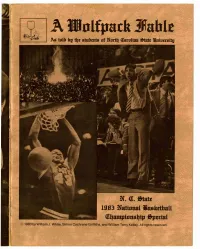

G Men-Cnc'h' 1I'nyatmu'

«'4 1i‘nyAtmu'. men-Cnc‘h‘g A iflflnlfpark Eflahle nce upon a time along Tobacco Road there The Pack rolled along and appeared to be getting its lived a kingdom of people called the forces aligned for many consecutive massacres, when Wolfpack. They resided on the west side of tragedy struck the team of roundballers. As the Pack faced ‘ Raleigh at a place called North Carolina State one of its stiffest conference foes, State’s main long-range University, or State for short. weapon fell victim to the blow of a Cavalier. Dereck Whit- Now these people had maintained this community for tenburg, who had led the troops in long-range hits (three- four score and a few more years. During that time they had point goals) was felled with a broken foot. acquired a great love for a game that was played during the Shock rocked the Kingdom. Many of the scribes wintertime. The State people took great pride in their abili- throughout the territory, with the stroke of a pen, wrote of ty to play this game called basketball or hoops by some of the Wolfpack’s demise. Sure enough, the Pack fell into a its most avid followers. slump and much of the Kingdom was losing confidence in The Wolfpack had accumulated one National Champion- their heralded hoopsters. ’1' ‘kl ship a few years before and yearned for another, although Had it not been for surprise efforts by some of the war- the years had been lean for almost a decade. After hiring a riors, indeed the doom of State might once again have new leader for their hoop squad, the people of State took a disappointed the Kingdom. -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Changes Ahead for AFCENT, Shaw Prized Treasures

IN SPORTS: Manning-Santee, Dalzell-Shaw meet in Game 2 of opening series B1 INSIDE Haley diplomacy Former S.C. governor does hands-on peacemaking with food for Syrian refugees A2 THURSDAY, JUNE 1, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Changes ahead for AFCENT, Shaw Relocation of 432nd Expeditionary Wing from Nevada could begin in November BY JIM HILLEY [email protected] about them and pray for them, lies are so excited, because they because we never know when know how awesome the local Shaw AFB Commander Col. and where they are going to go. community is,” Lasica said. Daniel Lasica said the base re- They are officially on the hook.” “They know how centrally locat- cently welcomed back the more In other news, Lasica said lead- ed the Midlands is, close to Co- than 300 airmen of the 29th Fight- ership of the 432nd Expeditionary lumbia, close to Charlotte, Myrtle er Squadron “Tigers” from Ba- Wing at Creech Air Force Base, Beach, Kiowa, Charleston ... all gram Air Field in Afghanistan. Nevada, including Col. Case Cun- those places.” Speaking at the Greater Sumter ningham, visited Shaw on Tues- Maj. Gen. Scott Zobrist, com- of Commerce Commander’s day. Plans call for the wing to re- mander of the 9th Air Force, was Breakfast Wednesday morning, locate to Shaw. also at the breakfast and said he he said their seven-month deploy- “Cunningham was not on the had a chance to talk to the com- ment was typical. deck for very long but literally his mander of one of the units. -

Takeaknee: an American Genealogy Olivia D. August

#TakeAKnee: An American Genealogy Olivia D. August Arlington, Virginia Bachelor of Arts in English and Religious Studies, University of Virginia, 2017 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2018 August 2 Honesty impels me to admit that such a stand will require willingness to suffer and sacrifice. So don’t despair if you are condemned and persecuted for righteousness’ sake. Whenever you take a stand for truth and justice, you are liable to scorn. Often you will be called an impractical idealist or a dangerous radical. Sometimes it might mean going to jail. It might even mean physical death. But if physical death is the price some must pay to free their children from a permanent life of psychological death, then nothing could be more Christian. Martin Luther King, Jr.1 In August 2016 San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began sitting for the national anthem during the NFL’s preseason. His protest went unnoticed for the first two games as he was wearing plainclothes on the bench, but on August 26, 2016, after the third game, he was approached by media wondering why he had remained seated: ‘I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,’ Kaepernick told NFL Media in an exclusive interview after the game. ‘To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.