Human Rights and Technology Sales: How Corporations Can Avoid Assisting Repressive Regimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions (January 1993 - April 2020) Huntington BAE Spirit Booz Allen L3Harris Precision Rolls- Airbus Boeing CACI Perspecta General Dynamics GE Honeywell Leidos SAIC Leonardo Technologies Lockheed Martin Ingalls Northrop Grumman Castparts Safran Textron Thales Raytheon Technologies Systems Aerosystems Hamilton Industries Royce Airborne tactical DHPC Technologies L3Harris airport Kopter Group PFW Aerospace to Aviolinx Raytheon Unisys Federal Airport security Hydroid radio business to Hutchinson airborne tactical security businesses Vector Launch Otis & Carrier businesses BAE Systems Dynetics businesses to Leidos Controls & Data Premiair Aviation radios business Fiber Materials Maintenance to Shareholders Linndustries Services to Valsef United Raytheon MTM Robotics Next Century Leidos Health to Distributed Energy GERAC test lab and Technologies Inventory Locator Service to Shielding Specialities Jet Aviation Vienna PK AirFinance to ettain group Night Vision business Solutions business to TRC Base2 Solutions engineering to Sopemea 2 Alestis Aerospace to CAMP Systems International Hamble aerostructure to Elbit Systems Stormscope product eAircraft to Belcan 2 GDI Simulation to MBDA Deep3 Software Apollo and Athene Collins Psibernetix ElectroMechanical Aciturri Aeronautica business to Aernnova IMX Medical line to TransDigm J&L Fiber Services to 0 Knight Point Aerospace TruTrak Flight Systems ElectroMechanical Systems to Safran 0 Pristmatic Solutions Next Generation 911 to Management -

SURVEILLE NSA Paper Based on D2.8 Clean JA V5

FP7 – SEC- 2011-284725 SURVEILLE Surveillance: Ethical issues, legal limitations, and efficiency Collaborative Project This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no. 284725 SURVEILLE Paper on Mass Surveillance by the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States of America Extract from SURVEILLE Deliverable D2.8: Update of D2.7 on the basis of input of other partners. Assessment of surveillance technologies and techniques applied in a terrorism prevention scenario. Due date of deliverable: 31.07.2014 Actual submission date: 29.05.2014 Start date of project: 1.2.2012 Duration: 39 months SURVEILLE WorK PacKage number and lead: WP02 Prof. Tom Sorell Author: Michelle Cayford (TU Delft) SURVEILLE: Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Commission Services) Executive summary • SURVEILLE deliverable D2.8 continues the approach pioneered in SURVEILLE deliverable D2.6 for combining technical, legal and ethical assessments for the use of surveillance technology in realistic serious crime scenarios. The new scenario considered is terrorism prevention by means of Internet monitoring, emulating what is known about signals intelligence agencies’ methods of electronic mass surveillance. The technologies featured and assessed are: the use of a cable splitter off a fiber optic backbone; the use of ‘Phantom Viewer’ software; the use of social networking analysis and the use of ‘Finspy’ equipment installed on targeted computers. -

Boeing Et L'industrie Française

Boeing France Boeing et l’industrie française L’innovation se nourrit d’une passion commune Boeing et l’industrie française L’innovation se nourrit d’une passion commune Boeing en France Le groupe Boeing 05 Boeing et la France, un partenariat fructueux 14 Premier groupe aéronautique mondial 06 L’élite de l’industrie française au service 15 80 ans de leadership dans l’aviation civile de l’excellence Boeing 16 Le 777, le long-courrier préféré du marché 07 14 fournisseurs ont rejoint la « Boeing French Team » 17 Le 747-8, le nouveau géant des airs depuis 2005 18 Une offre de services complète 08 L’industrie française à bord du 787 Dreamliner 19 Le 787 Dreamliner, l’avion de rêve 09 Nos partenaires témoignent 20 L’innovation et l’expertise au service de la défense 10 Boeing et Air France, des liens pérennes et de l’espace 11 Boeing et les compagnies françaises 22 Imaginer l’aéronautique de demain 12 Boeing, fournisseur de l’armée française 24 Une démarche de pionnier pour l’environnement 13 L’engagement auprès des Restos du Cœur 26 Un peu d’histoire Boeing France 03 Décrocher la lune Depuis près de cent ans, Boeing s’emploie à relever tous les défis. Des premiers avions de ligne à la conquête de la lune, ses réalisations, placées sous le signe de l’audace et de l’innovation, se sont traduites par de nombreux exploits technologiques et commerciaux. Mais rien n’est Boeing a prendre une décision unique avec la création jamais acquis, et chaque jour est à réinventer. -

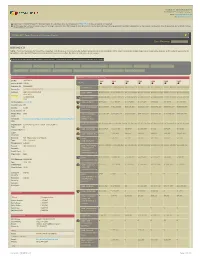

BOEING CO NOTE : If a Parent Company for This Entity Is Reported, Click the Link on Its Parent DUNS Number Below to See Its Consolidated Profile

Created on : 02/21/2013 01:35:14 © FEDMINE™ All Rights Reserved Email: [email protected] URL: www.fedmine.us ● Hyperlinks in FEDMINE HTML & PDF documents work for subscribers only. You may request a FREE TRIAL to view all reports in the system ● Parent & subsidiary company relationships are no longer included in the FPDS-NG data in order to honor the Federal Government’s licensing agreement with Dun & Bradstreet. For that reason it is possible those relationships do not reflect the most current status in our system FEDMINE™ PRIME CONTRACTOR COMPANY PROFILE LAST UPDATED: 07/30/2011 01:31:39 AM BOEING CO NOTE : If a Parent company for this entity is reported, click the link on its Parent DUNS number below to see its consolidated Profile. Parent subsidiary relationships are no longer provided due to the Federal Government's agreement with D&B, and therefore, some relationships may not reflect the most current status in our system. All OBLIGATED DOLLARS PERTAIN TO PRIME CONTRACTING DOLLARS ONLY. IF PURCHASED SEPARATELY SUBCONTRACTS DATA IS INCLUDED IN ALL PROFILES SUB CONTRACTS AWARDED VIEW PROFILE BY SUBSIDIARIES CONTRACT AWARDS IN LAST 30 DAYS CONTRACTS BY PLACE OF PERFORMANCE CONTRACTS BY CONTRACTING OFF. FEDBIZOPPS AWARDS GAO PROTESTS FILED BY COMPANY GWAC CONTRACTS CONTRACTS BY NAICS CODES CONTRACTS BY PSC CODES CONTRACTS BY SOCIO ECONOMIC STATUS CONTRACTS BY SETASIDE TYPE CONTRACTS BY PRICING TYPE ORGANIZATION DETAILS COMPARATIVE 5 - YEAR FEDERAL CONTRACTS VIEW DUNS: 009256819 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 Parent DUNS: 009256819 AGENCY Fedmine ID: F330698520 0 $ 7,039,132,983 $ 6,124,563,126 $ 5,166,127,597 $ 4,779,379,771 Known As: BOEING COMPANY THE 1700 - NAVY Address: 100 N RIVERSIDE PLZ CHICAGO 0 $ 2,077,542,702 $ 3,584,111,494 $ 3,187,150,820 $ 4,822,574,368 IL 60606-1501 2100 - ARMY USA GEO Location: FEDPOINT $ 12,277,811 $ 964,537,879 $ 1,590,564,876 $ 1,426,519,327 $ 1,806,894,750 9700 - DEFENSE County Code: 031 County: COOK $ 226,696 $ 1,186,915 $ 1,526,886 $ 1,615,465 $ 370,624 1500 - JUSTICE Cong. -

Shaping the Future Wind Tunnel Testing Helps Boeing Shape 737 MAX— and the Future of Flight

Frontierswww.boeing.com/frontiers JULY 2012 / Volume XI, Issue III Shaping the future Wind tunnel testing helps Boeing shape 737 MAX— and the future of flight PB BOEING FRONTIERS / JULY 2012 1 BOEING FRONTIERS / JULY 2012 On the Cover Tunnel vision Computer simulations are crucial in developing the aerodynamics of Boeing aircraft, but at some point it’s time to turn on the wind! From 22 the B-47 bomber to the 787 Dreamliner, what Boeing engineers learn from testing models in wind tunnels has shaped the future of flight. Today, another Boeing jet, the 737 MAX, is undergoing this rigorous testing that comes early in the development process. COVER IMAGE: BOEING ENGINEER JIM CONNER PREPARES A MODEL OF THE 737 MAX FOR TESTING IN THE TRANSONIC WIND TUNNEL IN SEATTLE. BOB FERGUSON/BOEING PHOTO: A LOOK AT THE HIGH-SPEED DIFFUSER OF THE BOEING VERTICAL/SHORT TAKEOFF AND LANDING WIND TUNNEL IN PHILADELPHIA. FRED TROILO/BOEING Ad watch The stories behind the ads in this issue of Frontiers. Inside cover: Page 6: Back cover: This ad was created This ad for the new Every July, the Boeing to highlight Boeing’s 747-8 Intercontinental is Store commemorates Commercial Crew running in Chinese trade Boeing’s anniversary Development System, and business publications with a weeklong a reliable, cost-effective and Aviation Week. celebration, offering and low-risk solution The headline speaks to special merchandise, for commercial space the airplane’s striking gifts and free birthday transportation. The beauty (new Boeing Sky cake in the stores. ad is running in trade Interior), classic elegance This ad for the 2012 publications. -

By Working with These Institutions and Establishing International

GlOBal BOEING “ By working with these institutions Boeing’s international and establishing international strategy focuses research sites, we demonstrate on mutually that we’re committed to building beneficial a long-term presence in partnerships important markets.” By Bill seil – John Tracy, Boeing chief technology officer and senior vice president, Engineering, Operations & Technology round the globe, Boeing is providing the best and most innovative Boeing is enhancing its presence includes entities from 35 nations for sites, we demonstrate that we’re pHOTOS: Boeing’s partnerships developing partnerships that products and services at affordable prices. internationally by hiring local talent and research in diverse areas including committed to building a long-term around the world are fueling growth benefit its customers, business The company also has worked to meet deploying U.S. employees at key locations biofuels, manufacturing processes, presence in important markets.” in research and development and a making the company more competitive. partners and local economies. In return, the specific needs of individual customers around the world. More than 8,500 of structures and robotics. In addition to providing the best, (Clockwise, from top left) Composites the company is strengthened by growing and regions. Boeing’s 164,000 employees work “Because there’s more than $1 trillion most advanced products, the company research in the United Kingdom; new sales and tapping the best technologies “Doing business in today’s global outside the United -

Supreme Court of the United States

Nos. 19-416 & 19-453 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States NESTLÉ USA, INC., Petitioner, v. JOHN DOE I, et al., Respondents. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– CARGILL, INC., Petitioner, v. JOHN DOE I, et al., Respondents. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRcuIT BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE ACCESS NOW, ARTICLE 19, CENTER FOR LONG-TERM CYBERSECURITY, ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION, PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL AND PROFESSOR RONALD DEIBERT IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS SOPHIA COPE Counsel of Record CINDY COHN ELECTRONic FRONTIER FOUNDATION 815 Eddy Street San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae 298803 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................i TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES ..............iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..................1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................5 ARGUMENT....................................7 I. ATS Policy Supports Preserving U.S. Corporate Liability Under the Statute.........7 II. United Nations Policy Supports Preserving U.S. Corporate Liability Under the ATS.......8 III. The Technology Industry Plays a Major Role in Human Rights Abuses Worldwide.....11 A. Researchers Chronicle the Widespread Problem of Technology Companies’ Complicity in Human Rights Abuses .....12 B. American Technology Companies Have Been Complicit in Human Rights Abuses in Foreign Countries............18 ii Table of Contents Page IV. Voluntary Mechanisms for Holding the Technology Industry Accountable for Human Rights Abuses are Inadequate ..............25 A. Limits of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives ...28 B. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises ..........................29 C. Global Network Initiative...............33 CONCLUSION .................................35 iii TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES Page Cases Balintulo v. Ford Motor Co., 796 F.3d 160 (2d Cir. -

PDF Download

Frontierswww.boeing.com/frontiers SEPTEMBER 2010 / Volume IX, Issue V Cyber secure Protecting vital information networks is a fast-growing market for Boeing BOEING FRONTIERS / SEPTEMBER 2010 Frontiers Publisher: Tom Downey Editorial director: Anne Toulouse EDITORIAL TEAM Executive editor: Paul Proctor: 312-544-2938 Editor: James Wallace: 312-544-2161 table of contents Managing editor: INSIDE Vineta Plume: 312-544-2954 Service tradition Art and design director: Brandon Luong: 312-544-2118 Boeing employees in Utah have earned 16 a reputation for taking on a variety of work Graphic designer: 32 Changing lives 07 Leadership Message and performing well, whether it’s building Rick Moore: 314-233-5758 Boeing volunteers from around the world, along with family and friends, took time Boeing Defense, Space & Security parts of the company’s commercial Photo director: out on July 17 to change lives by helping build homes, work with young people has a bold vision for future growth as Bob Ferguson: 312-544-2132 jetliners or supporting defense programs. in schools, serve meals in homeless shelters and perform many other community Salt Lake City also is the only Boeing site it works to expand its core business Commercial Airplanes editor: services. It was all part of Boeing’s first Global Day of Service, which was timed to in the United States that sends no waste and reposition in a time of constrained Don Smith: 206-766-1329 commemorate the company’s founding in mid-July 1916. PHoto: JESSICA OYANAGI/BOEING to landfills—what doesn’t become an Defense, Space & Security editor: defense budgets. -

Boeing Is Setting New Standards for Efficiency, Environmental Performance and Noise Reduction

2012 Environment Report Boeing is setting new standards for efficiency, environmental performance and noise reduction. 2012 Environment Report Table of Contents 03 05 16 Our Commitment Our Actions Our Results Message from Jim McNerney Boeing is investing in the next Boeing has reduced its envi- and Kim Smith. generation of environmental ronmental footprint at a time advances. of significant growth. 03 05 16 Message from Jim McNerney and Designing the Future Performance Kim Smith 07 18 04 Inspring the Industry Carbon Dioxide Emissions Performance Targets 10 19 Cleaner Products Energy Use 12 20 Cleaner Factories Hazardous Waste 14 21 Remediation Water Intake 22 Solid Waste Diverted From Landfills 23 Toxic Release Inventory 24 International 25 Recognition » To learn more, go to www.boeing.com/environment 2 Our Commitment BOEING 2012 ENVIRONMENT REPORT Message From Jim McNerney and Kim Smith At Boeing, we are focused on creating cleaner, more efficient flight. Each new generation of products we bring to the marketplace is quieter, consumes less fuel and is better for the environment. The 747-8 and 787 Dreamliner — with Looking to the future, we will continue basis. At the time, we anticipated these smaller noise and emissions profiles than devoting a significant portion of our R&D goals would equate to a 25 percent reduc- airplanes they replace — entered into ser- efforts to develop cleaner, more efficient air- tion on a revenue-adjusted basis. vice last year. We also launched the 737 craft. First flight of the Phantom Eye — an Since then, we have experienced un- MAX with a 13 percent smaller carbon unmanned, high-altitude aircraft powered precedented growth in our business. -

BOEING CO NOTE : If a Parent Company for This En�Ty Is Reported, Click the Link on Its Parent DUNS Number Below to See Its Consolidated Profile

Created on : 06/08/2013 15:53:42 © FEDMINE™ All Rights Reserved Email: [email protected] URL: www.fedmine.us Hyperlinks in FEDMINE HTML & PDF documents work for subscribers only. You may request a FREE TRIAL to view all reports in the system Parent & subsidiary company relaonships are no longer included in the FPDS-NG data in order to honor the Federal Governmentâs licensing agreement with Dun & Bradstreet. For that reason it is possible those relaonships do not reflect the most current status in our system FEDMINE™ PRIME CONTRACTOR COMPANY PROFILE LAST UPDATE D: 07/30/2011 01:31:39 AM BOEING CO NOTE : If a Parent company for this enty is reported, click the link on its Parent DUNS number below to see its consolidated Profile. Parent subsidiary relaonships are no longer provided due to the Federal Government's agreement with D&B, and therefore, some relaonships may not reflect the most current status in our system. All OBLIGATED DOLLARS PERTAIN TO PRIME CONTRACTING DOLLARS ONLY. IF PURCHASED SEPARATELY SUBCONTRACTS DATA IS INCLUDED IN ALL PROFILES SUB CONTRACTS AWARDED VIEW PROFILE BY SUBSIDIARIES CONTRACT AWARDS IN LAST 30 DAYS CONTRACTS BY PLACE OF PERFORMANCE CONTRACTS BY CONTRACTING OFF. FEDBIZOPPS AWARDS GAO PROTESTS FILED BY COMPANY GWAC CONTRACTS CONTRACTS BY NAICS CODES CONTRACTS BY PSC CODES CONTRACTS BY SOCIO ECONOMIC STATUS CONTRACTS BY SETASIDE TYPE CONTRACTS BY PRICING TYPE ORGANIZATION DETAILS COMPARATIVE 7 - YEAR FEDERAL CONTRACTS VIEW DUNS: 009256819 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 Parent DUNS: NONE AGENCY Fedmine ID: -

Panopticon – Surveillance and Privacy in the Internet Age

Sequence Number: FJL-LAK1 Panopticon – Surveillance and Privacy in the Internet Age February 27, 2009 Michael Walter-Echols Approved: ______________________________________ F. J. Looft, Professor and Head Electrical and Computer Engineering An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Abstract The right to privacy has been central to democratic society since its inception. In turbulent times, the desire for enhanced national security is often seen to trump an individual’s right to privacy. Along with laws permitting expanded government control over the lives of its people, technology has increased the potential for surveillance of the average citizen. This project reviews the concept of privacy rights and the history of privacy. Secondly, it examines the changes to privacy rights that have occurred due to recent events, and evaluate if any significant enhancement to security is thereby achieved. Finally, it provides recommendations on how personal and public security can be enhanced while remaining sensitive to privacy considerations. 2 Table of Contents Abstract.................................................................................................................................................2 Chapter 1: Introduction........................................................................................................................5 Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 -

Israeli Spy Companies

Israeli Spy Companies: Verint and Narus By Richard Sanders ism specialist and military-intelligence had stolen sensitive technology to officer who served 19 years in Turkey, manufacture artillery gun tubes, ob- n the mid-2000s, two Israeli spy Italy, Germany, and Spain. He notes that tained classified plans for a recon- companies (Narus and Verint) were Israel “always features prominently” in naissance system, and passed sensi- Icaught in the centre of a huge scan- the FBI’s annual report, “Foreign Eco- tive aerospace designs to unauthor- dal involving the wiretapping of virtu- nomic Collection and Industrial Espio- ized users. An Israeli company was ally all US phone and internet mes- nage.” Its 2005 report, he says, stated: caught monitoring a Department of sages. Their mass surveillance services “‘Israel has an active program to Defense telecommunications system were used by America’s two largest tel- gather proprietary information to obtain classified information.” ecom companies, AT&T and Verizon. within the US. These collection ac- Another ex-CIA officer who ex- (See AT&T pp.7-8, and Verizon in ta- tivities are primarily directed at ob- pressed grave concerns about Israel’s ble, “CPP Investments,” p.53.) taining information on military sys- spying is Robert David Steele. He said These telecom giants, which to- tems and advanced computing ap- “Israeli penetration of the entire US tel- gether control 80% of the US market, plications that can be used in Isra- ecommunications system means that were turning over all of their custom- el’s sizable armaments industry.’ It NSA’s warrantless wiretapping actually ers’ internet communications and phone adds that Israel recruits spies, uses means Israeli warrantless wiretapping.” call records to the US National Secu- electronic methods, and carries out Jane’s Intelligence Group re- rity Agency (NSA).