The Emerging Minoan Thalassocracy of 1628 BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Paper

Alexandra Salichou The mobility of goods and the provisioning of buildings ٭within the Late Minoan IB settlement of Kato Zakros Abstract The street networks of Minoan urban sites were primary used for the communication and circulation of the people within the settlement, as well as for the mobility of the goods and products that either covered the daily needs of the inhabitants or were part of the economic life of the community. Focusing on the Neopalatial settlement of Kato Zakros, this paper aims to examine the significance of its street network in the political economy of the settlement and in the domestic economy of individual buildings. Certain issues will be raised, associated with the categories of the goods that were mobilised, the means of such mobilisation and the distances that had to be covered; in that perspective, we will also examine the features that the road network had (or should have had) in order to facilitate this transportation, and to what extent the internal organization of the buildings took into account their provisioning needs. A general brief discussion will follow on the formation processes of the street system at Kato Zakros, with references to the neighbouring Neopalatial town of Palaikastro. Keywords: Far East Crete, Zakros, Prehistory, Bronze Age, architecture, street system, street network, Neopalatial, settlement In early preindustrial settlements, extensive and well-planned street systems are considered to be a key criterion for the identification of their urban character; in fact, advanced street networks -

Golden Age of the Minoans

Golden Age of the Minoans Travel Passports Please ensure your 10-year British Passport is not Baggage Allowance out of date and is valid for a full six months We advise that you stick to the baggage beyond the duration of your visit. The name on allowances advised. If your luggage is found to be your passport must match the name on your flight heavier than the airlines specified baggage ticket/E-ticket, otherwise you may be refused allowance the charges at the airport will be hefty. boarding at the airport. With Easyjet your ticket includes one hold bag of Visas up to 23kg plus one cabin bag no bigger than 56 x Visas are not required for Greece for citizens of 45 x 25cm including handles, pockets and wheels. Great Britain and Northern Ireland. For all other passport holders please check the visa For more information please visit requirements with the appropriate embassy. www.easyjet.com Greek Consulate: 1A Holland Park, London W11 3TP. Tel: 020 7221 6467 Labels Please use the luggage labels provided. It is useful to have your home address located inside your suitcase should the label go astray. Tickets Included with this documentation is an e-ticket, Departure Tax which shows the reference number for your flight. UK Flight Taxes are included in the price of your EasyJet have now replaced all their airport check- holiday. in desks with EasyJet Baggage Drop desks. Therefore, you must check-in online and print Transfers out your boarding passes before travelling. On arrival at Heraklion Airport please collect your Checking in online also provides the opportunity luggage and exit the luggage area and proceed for you to pre-book seats, if you wish, at an until you are completely out of the airport additional cost. -

Study Guide Academic Year 2015-2016

SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND CULTURAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY & CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Study Guide Academic Year 2015-2016 DHACRM Study Guide, 2015-16 2 Table of Contents The University of the Peloponnese ........................................................................................... 6 Department of History, Archaeology & Cultural Resources Management ................ 8 Undergraduate Studies at DHACRM ....................................................................................... 12 Overview of Courses by Semester, No. of Teaching Units & ECTS .............................. 13 IMPORTANT NOTES! .................................................................................................................... 21 Course Guide .................................................................................................................................... 22 CORE COURSES ....................................................................................................................... 22 12Κ1 Ancient Greek Philology: The Homeric Epics - Dramatic Poetry ........... 22 12Κ2 Introduction to the Study of History ................................................................. 22 12Κ3 Introduction to Ancient History ......................................................................... 23 12Κ5 What is Archaeology? An Introduction ............................................................ 23 12Κ6 Prehistoric Archaeology: Τhe Stone and the Bronze Age ......................... 24 12K8 Byzantine -

Recent Trends in the Archaeology of Bronze Age Greece

J Archaeol Res (2008) 16:83–161 DOI 10.1007/s10814-007-9018-7 Aegean Prehistory as World Archaeology: Recent Trends in the Archaeology of Bronze Age Greece Thomas F. Tartaron Published online: 20 November 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract This article surveys archaeological work of the last decade on the Greek Bronze Age, part of the broader discipline known as Aegean prehistory. Naturally, the literature is vast, so I focus on a set of topics that may be of general interest to non-Aegeanists: chronology, regional studies, the emergence and organization of archaic states, ritual and religion, and archaeological science. Greek Bronze Age archaeology rarely appears in the comparative archaeological literature; accord- ingly, in this article I place this work in the context of world archaeology, arguing for a reconsideration of the potential of Aegean archaeology to provide enlightening comparative material. Keywords Archaeology Á Greece Á Bronze Age Á Aegean prehistory Introduction The present review updates the article by Bennet and Galaty (1997) in this journal, reporting work published mainly between 1996 and 2006. Whereas they charac- terized trends in all of Greek archaeology, here I focus exclusively on the Bronze Age, roughly 3100–1000 B.C. (Table 1). The geographical scope of this review is more or less the boundaries of the modern state of Greece, rather arbitrarily of course since such boundaries did not exist in the Bronze Age, nor was there a uniform culture across this expanse of space and time. Nevertheless, distinct archaeological cultures flourished on the Greek mainland, on Crete, and on the Aegean Islands (Figs. -

THE NATURE of the THALASSOCRACIES of the SIXTH-CENTURY B. C. by CATHALEEN CLAIRE FINNEGAN B.A., University of British Columbia

THE NATURE OF THE THALASSOCRACIES OF THE SIXTH-CENTURY B. C. by CATHALEEN CLAIRE FINNEGAN B.A., University of British Columbia, 1973 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1975 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my writ ten pe rm i ss ion . Department of plassips. The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date October. 197 5. ~t A ~ A A P. r~ ii The Nature of the Thalassocracies of the Sixth-Century B. C. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to study the nature and extent of the sixth century thalassocracies through the available ancient evidence, particularly the writings of Herodotus and Thucydides. In Chapter One the evidence for their existence is established and suggested dates are provided. Chapter Two is a study of their naval aspects and Chapter Three of their commercial aspects. This study leads to the conclusion that these thalassocracies were unaggressive mercantile states, with the exception of Samos during Polycrates' reign. -

Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey

Oral Tradition, 31/1 (2017):3-50 Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey Gregory Nagy Introduction I explore here the kaleidoscopic world of Homer and Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, combining it with a synchronic perspective. The terms synchronic and diachronic, as I use them here, come from linguistics.1 When linguists use the word synchronic, they are thinking of a given structure as it exists in a given time and space; when they use diachronic, they are thinking of that structure as it evolves through time.2 From a diachronic perspective, the structure that we know as Homeric poetry can be viewed, I argue, as an evolving medium. But there is more to it. When you look at Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, you will see not only an evolving medium of oral poetry. You will see also a medium that actually views itself diachronically. In other words, Homeric poetry demonstrates aspects of its own evolution. A case in point is “the Cretan Odyssey”—or, better, “a Cretan Odyssey”—as reflected in the “lying tales” of Odysseus in the Odyssey. These tales, as we will see, give the medium an opportunity to open windows into an Odyssey that is otherwise unknown. In the alternative universe of this “Cretan Odyssey,” the adventures of Odysseus take place in the exotic context of Minoan-Mycenaean civilization. Part 1: Minoan-Mycenaean Civilization and Memories of a Sea-Empire3 Introduction From the start, I say “Minoan-Mycenaean civilization,” not “Minoan” and “Mycenaean” separately. This is because elements of Minoan civilization become eventually infused with elements we find in Mycenaean civilization. -

Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials

MORTUARY VARIABILITY IN EARLY IRON AGE CRETAN BURIALS Melissa Suzanne Eaby A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Carla M. Antonaccio Jodi Magness G. Kenneth Sams Nicola Terrenato UMI Number: 3262626 Copyright 2007 by Eaby, Melissa Suzanne All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3262626 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © 2007 Melissa Suzanne Eaby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MELISSA SUZANNE EABY: Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) The Early Iron Age (c. 1200-700 B.C.) on Crete is a period of transition, comprising the years after the final collapse of the palatial system in Late Minoan IIIB up to the development of the polis, or city-state, by or during the Archaic period. Over the course of this period, significant changes occurred in settlement patterns, settlement forms, ritual contexts, and most strikingly, in burial practices. Early Iron Age burial practices varied extensively throughout the island, not only from region to region, but also often at a single site; for example, at least 12 distinct tomb types existed on Crete during this time, and both inhumation and cremation were used, as well as single and multiple burial. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

Sample File Heavily on Patriotism and National Identity

Empire Builder Kit Preface ............................................................ 2 Government Type Credits & Legal ................................................ 2 An empire has it rulers. The type of ruler can How to Use ..................................................... 2 often determine the character of a nation. Are Government Types ......................................... 3 they a democratic society that follows the will Simple Ruler Type ....................................... 3 of the people, or are they ruled by a harsh dictator who demand everyone caters to their Expanded Ruler Type .................................. 4 every whim. They could even be ruled by a Also Available ................................................ 10 group of industrialists whose main goal is the acquisition of wealth. Coming Soon ................................................. 10 This part of the Empire Builder kit outlines some of the more common, and not so common, types of ruler or government your empire or country may possess. Although designed with fantasy settings in mind, most of the entries can be used in a sci-fi or other genre of story or game. There are two tables in this publication. One for simple and quick governments and A small disclaimer – A random generator will another that is expanded. Use the first table never be as good as your imagination. Use for when you want a common government this to jump start your own ideas or when you type or a broad description, such as need to fill in the blank. democracy or monarchy. Use the second/expanded table for when you want something that is rare or you want more Sample details,file such as what type of democracy etc. If you need to randomly decide between the two tables, then roll a d20. If you get 1 – 18 then use the simple table, otherwise use the expanded one. -

Athenian Democratic Ideology

Athenian Democratic Ideology We aim to bring together scholars interested in the rhetorical devices, media, and techniques used to promote or attack political ideologies or achieve political agendas during fifth- and fourth-century BCE Athens. A senior scholar with expertise in this area has agreed to preside over the panel and facilitate discussion. “Imperial Society and Its Discontents” investigates challenges to an important aspect of Athenian imperial ideology, namely pride in the fleet’s ability to keep Athens fed and the empire secure during the so-called First Peloponnesian War and the Peloponnesian War proper. The author takes on Ober’s (1998) minimizing of the role the empire played in enabling the democracy’s existence. The author focuses on Herodotus’ Aces River vignette (Book 3), in which the Persians employ heavy-handed imperial methods to control water resources. Given the Athenians’ adoption of forms of oriental despotism in their own imperial practices (Raaflaub 2009), Herodotus plays the role of ‘tragic warner,’ intending that this story serve as a negative commentary on Athenian imperialism. Moving from the empire to the dêmos, “The Importance of Being Honest: Truth in the Attic Courtroom” examines whether legal proceedings in Athens were “honor games” (Humphreys 1985; Osborne 1985) or truly legitimate legal proceedings (Harris 2005). The author argues that both assertions are correct, because while honor games were being played, the truth of the charges still was of utmost importance. Those playing “honor games” had to keep to the letter of the law, as evidence from Athenian oratory demonstrates. The prosecutor’s honesty was a crucial part of these legal proceedings, and any honor rhetoric went far beyond mere status-seeking. -

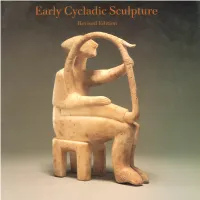

Early Cycladic Sculpture: an Introduction: Revised Edition

Early Cycladic Sculpture Early Cycladic Sculpture An Introduction Revised Edition Pat Getz-Preziosi The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California © 1994 The J. Paul Getty Museum Cover: Early Spedos variety style 17985 Pacific Coast Highway harp player. Malibu, The J. Paul Malibu, California 90265-5799 Getty Museum 85.AA.103. See also plate ivb, figures 24, 25, 79. At the J. Paul Getty Museum: Christopher Hudson, Publisher Frontispiece: Female folded-arm Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor figure. Late Spedos/Dokathismata variety. A somewhat atypical work of the Schuster Master. EC II. Library of Congress Combining elegantly controlled Cataloging-in-Publication Data curving elements with a sharp angularity and tautness of line, the Getz-Preziosi, Pat. concept is one of boldness tem Early Cycladic sculpture : an introduction / pered by delicacy and precision. Pat Getz-Preziosi.—Rev. ed. Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum Includes bibliographical references. 90.AA.114. Pres. L. 40.6 cm. ISBN 0-89236-220-0 I. Sculpture, Cycladic. I. J. P. Getty Museum. II. Title. NB130.C78G4 1994 730 '.0939 '15-dc20 94-16753 CIP Contents vii Foreword x Preface xi Preface to First Edition 1 Introduction 6 Color Plates 17 The Stone Vases 18 The Figurative Sculpture 51 The Formulaic Tradition 59 The Individual Sculptor 64 The Karlsruhe/Woodner Master 66 The Goulandris Master 71 The Ashmolean Master 78 The Distribution of the Figures 79 Beyond the Cyclades 83 Major Collections of Early Cycladic Sculpture 84 Selected Bibliography 86 Photo Credits This page intentionally left blank Foreword The remarkable stone sculptures pro Richmond, Virginia, Fort Worth, duced in the Cyclades during the third Texas, and San Francisco, in 1987- millennium B.C. -

Art of the Ancient Aegean AP Art History Where Is the Aegean Exactly? 3 Major Periods of Aegean Art

Art of the Ancient Aegean AP Art History Where Is the Aegean Exactly? 3 Major Periods of Aegean Art: ● Cycladic: 2500 B.C.E - 1900 B.C.E ● Located in Aegean Islands ● Minoan: 2000 B.C.E - 1400 B.C.E ● Located on the island of Crete ● Mycenaean 1600 B.C.E – 1100 B.C.E ● Located in Greece All 3 overlapped with the 3 Egyptian Kingdoms. Evidence shows contact between Egypt and Aegean. Digging Into the Aegean ● Similar to Egypt, archaeology led to understanding of Aegean civilization through art ● 1800’s: Heinrich Schliemann (Germany) discovers Mycenaean culture by excavating ruins of Troy, Mcyenae ● 1900: Sir Arthur Evans excavates Minoan palaces on Crete ● Both convinced Greek myths were based on history ● Less is known of Aegean cultures than Egypt, Mesopotamia The Aegean Sailors ● Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, Aegean cultures were not land locked. ● Access to sea allowed for expansion and exploring, adaptation of other cultures (Egypt) ● Much information about Aegean culture comes from items found on shipwrecks ● Egyptian scarabs ● African ivory, ebony ● Metal ore imports The Cycladic Culture ● Cyclades: Circle of Islands ● Left no written records, essentially prehistoric ● Artifacts are main info source ● Originally created with clay, later shifting to marble ● Most surviving objects found in grave sites like Egypt ● Figures were placed near the dead Cycladic Figures ● Varied in size (2” to 5 feet) ● Idols from Greek word Eidolon-image ● Primarily female (always nude), few males ● Made of marble, abundant in area ● Feet too small to stand,