Emily Poelina-Hunter, 'Cataloguing Cycladic Figures'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide Academic Year 2015-2016

SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND CULTURAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY & CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Study Guide Academic Year 2015-2016 DHACRM Study Guide, 2015-16 2 Table of Contents The University of the Peloponnese ........................................................................................... 6 Department of History, Archaeology & Cultural Resources Management ................ 8 Undergraduate Studies at DHACRM ....................................................................................... 12 Overview of Courses by Semester, No. of Teaching Units & ECTS .............................. 13 IMPORTANT NOTES! .................................................................................................................... 21 Course Guide .................................................................................................................................... 22 CORE COURSES ....................................................................................................................... 22 12Κ1 Ancient Greek Philology: The Homeric Epics - Dramatic Poetry ........... 22 12Κ2 Introduction to the Study of History ................................................................. 22 12Κ3 Introduction to Ancient History ......................................................................... 23 12Κ5 What is Archaeology? An Introduction ............................................................ 23 12Κ6 Prehistoric Archaeology: Τhe Stone and the Bronze Age ......................... 24 12K8 Byzantine -

Recent Trends in the Archaeology of Bronze Age Greece

J Archaeol Res (2008) 16:83–161 DOI 10.1007/s10814-007-9018-7 Aegean Prehistory as World Archaeology: Recent Trends in the Archaeology of Bronze Age Greece Thomas F. Tartaron Published online: 20 November 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract This article surveys archaeological work of the last decade on the Greek Bronze Age, part of the broader discipline known as Aegean prehistory. Naturally, the literature is vast, so I focus on a set of topics that may be of general interest to non-Aegeanists: chronology, regional studies, the emergence and organization of archaic states, ritual and religion, and archaeological science. Greek Bronze Age archaeology rarely appears in the comparative archaeological literature; accord- ingly, in this article I place this work in the context of world archaeology, arguing for a reconsideration of the potential of Aegean archaeology to provide enlightening comparative material. Keywords Archaeology Á Greece Á Bronze Age Á Aegean prehistory Introduction The present review updates the article by Bennet and Galaty (1997) in this journal, reporting work published mainly between 1996 and 2006. Whereas they charac- terized trends in all of Greek archaeology, here I focus exclusively on the Bronze Age, roughly 3100–1000 B.C. (Table 1). The geographical scope of this review is more or less the boundaries of the modern state of Greece, rather arbitrarily of course since such boundaries did not exist in the Bronze Age, nor was there a uniform culture across this expanse of space and time. Nevertheless, distinct archaeological cultures flourished on the Greek mainland, on Crete, and on the Aegean Islands (Figs. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

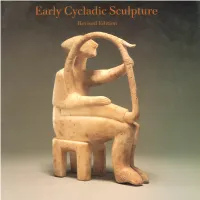

Early Cycladic Sculpture: an Introduction: Revised Edition

Early Cycladic Sculpture Early Cycladic Sculpture An Introduction Revised Edition Pat Getz-Preziosi The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California © 1994 The J. Paul Getty Museum Cover: Early Spedos variety style 17985 Pacific Coast Highway harp player. Malibu, The J. Paul Malibu, California 90265-5799 Getty Museum 85.AA.103. See also plate ivb, figures 24, 25, 79. At the J. Paul Getty Museum: Christopher Hudson, Publisher Frontispiece: Female folded-arm Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor figure. Late Spedos/Dokathismata variety. A somewhat atypical work of the Schuster Master. EC II. Library of Congress Combining elegantly controlled Cataloging-in-Publication Data curving elements with a sharp angularity and tautness of line, the Getz-Preziosi, Pat. concept is one of boldness tem Early Cycladic sculpture : an introduction / pered by delicacy and precision. Pat Getz-Preziosi.—Rev. ed. Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum Includes bibliographical references. 90.AA.114. Pres. L. 40.6 cm. ISBN 0-89236-220-0 I. Sculpture, Cycladic. I. J. P. Getty Museum. II. Title. NB130.C78G4 1994 730 '.0939 '15-dc20 94-16753 CIP Contents vii Foreword x Preface xi Preface to First Edition 1 Introduction 6 Color Plates 17 The Stone Vases 18 The Figurative Sculpture 51 The Formulaic Tradition 59 The Individual Sculptor 64 The Karlsruhe/Woodner Master 66 The Goulandris Master 71 The Ashmolean Master 78 The Distribution of the Figures 79 Beyond the Cyclades 83 Major Collections of Early Cycladic Sculpture 84 Selected Bibliography 86 Photo Credits This page intentionally left blank Foreword The remarkable stone sculptures pro Richmond, Virginia, Fort Worth, duced in the Cyclades during the third Texas, and San Francisco, in 1987- millennium B.C. -

Art of the Ancient Aegean AP Art History Where Is the Aegean Exactly? 3 Major Periods of Aegean Art

Art of the Ancient Aegean AP Art History Where Is the Aegean Exactly? 3 Major Periods of Aegean Art: ● Cycladic: 2500 B.C.E - 1900 B.C.E ● Located in Aegean Islands ● Minoan: 2000 B.C.E - 1400 B.C.E ● Located on the island of Crete ● Mycenaean 1600 B.C.E – 1100 B.C.E ● Located in Greece All 3 overlapped with the 3 Egyptian Kingdoms. Evidence shows contact between Egypt and Aegean. Digging Into the Aegean ● Similar to Egypt, archaeology led to understanding of Aegean civilization through art ● 1800’s: Heinrich Schliemann (Germany) discovers Mycenaean culture by excavating ruins of Troy, Mcyenae ● 1900: Sir Arthur Evans excavates Minoan palaces on Crete ● Both convinced Greek myths were based on history ● Less is known of Aegean cultures than Egypt, Mesopotamia The Aegean Sailors ● Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, Aegean cultures were not land locked. ● Access to sea allowed for expansion and exploring, adaptation of other cultures (Egypt) ● Much information about Aegean culture comes from items found on shipwrecks ● Egyptian scarabs ● African ivory, ebony ● Metal ore imports The Cycladic Culture ● Cyclades: Circle of Islands ● Left no written records, essentially prehistoric ● Artifacts are main info source ● Originally created with clay, later shifting to marble ● Most surviving objects found in grave sites like Egypt ● Figures were placed near the dead Cycladic Figures ● Varied in size (2” to 5 feet) ● Idols from Greek word Eidolon-image ● Primarily female (always nude), few males ● Made of marble, abundant in area ● Feet too small to stand, -

The Annual of the British School at Athens

The Annual of the British School at Athens http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH Additional services for The Annual of the British School at Athens: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Cretan Palaces and the Aegean Civilization. II Duncan Mackenzie The Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 12 / November 1906, pp 216 - 258 DOI: 10.1017/S0068245400008091, Published online: 18 October 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068245400008091 How to cite this article: Duncan Mackenzie (1906). Cretan Palaces and the Aegean Civilization. II. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 12, pp 216-258 doi:10.1017/S0068245400008091 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 08 May 2015 CRETAN PALACES AND THE AEGEAN CIVILIZATION. II. IN my previous paper1 on Cretan Palaces and the Aegean Civilization I sought to give a general account of the architectural evidence resulting from excavation, in its bearing on the disputed question as to the continuity of Aegean culture throughout the course of its development. It will now be advisable to consider the problems involved on a wider basis, in the light of the objects other than architectural, found in Crete and elsewhere in the Aegean world. The Carian Hypothesis as to the Origins of the Aegean Civilization. That the implications of the question are of an ethnological character will at this stage in the inquiry be generally admitted. And here it will be convenient to take as our point of departure a standpoint that may now perhaps be regarded as pretty general, though negative in its bearings, and which is to the effect that the originators of the Aegean civilization, at any rate in its pre-Mycenaean phases, were not ' Achaeans' in the vague general sense of being a people from the mainland of Greece. -

Greece Timeline

Greece Timeline http://ancient-greece.org/resources/timeline.html Resources Greece Timeline Timeline Pictures Posters Teachers & Students 8000 BCE Mesolithic Period Desktop Wallpaper (8300-7000) Related Pages Earliest evidence of burials found in 7250 BCE Franchthi Cave in the Argolid, Greece Map of Ancient Grece Evidence of food producing economy, 7000 BCE Neolithic Period simple hut construction, and seafaring in (7000-3000 BCE) mainland Greece and the Aegean Explore More First "Megaron House" at Sesclo, in 5700 BCE central Greece Links: Alexander the Great Evidence of earliest fortifications at 3400 BCE Chronology Dimini, Greece The timeline of Greek 3000 BCE Mathematecians Houses of Vasiliki and Myrtos Aegean Bronze Age Messara Tholoi or Early Bronze Age Mathematecians born in House of Tiles at Lerna (3000-2000) Greece Minoan Prepalatial or: EMIA, EMIB Timeline of Greek (3000-2600 BCE) Drama Early Cycladic Culture Greek and Roman (3200-2000) Theater and Theatrical Early Helladic Period Masks Timeline (3000-2000) Full Chronology of Mathematics (including Greek mathematicians) 2600 BCE Minoan Prepalatial Period A Detailed Chronology of or: EMIIA, EMIIB, MMIII Greek History (2600-2000 BCE) A New Bronze Age Chronology (more) Destruction of Minoan settlements 2000 BCE Minoan Protopalatial The Thera (Santorini) Period Volcanic Eruption and or: MMIA, MMIB, MMI IA, the Absolute Chronology MMI IB, MMI IIA, MMI of the Aegean Bronze IIB, LMIA Early Age (1900-1700 BCE) Assiros Phases (Revised Early Middle Cycladic (2000-1600 BCE) chronology of -

Review of Aegean Prehistory I: the Islands of the Aegean Author(S): Jack L

Review of Aegean Prehistory I: The Islands of the Aegean Author(s): Jack L. Davis Reviewed work(s): Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 699-756 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/505192 . Accessed: 02/05/2012 08:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org Review of Aegean Prehistory I: The Islands of the Aegean JACK L. DAVIS INTRODUCTION of the Bronze Age, and it is no surprise that its se- formed the basis for a tripartite Cycladic chro- Not so long ago the islands of the Aegean (fig. 1) quence established to Helladic and Minoan were considered by many to be the backwater of Greek nology, parallel on the Greek mainland and Crete. The exis- prehistory.' Any synthesis of the field had perforce phases tence of a Neolithic in the islands, on Keos, to base its conclusions almost exclusively upon data particularly and Chios, had been demonstrated but in collected before the turn of the century. -

Through a Glass Darkly': Obsidian And

`THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY': OBSIDIAN AND SOCIETY IN THE SOUTHERN AEGEAN EARLY BRONZE AGE Tristan Carter Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London University. August 1998. BILL LONDON U1JIV. THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY': OBSIDIAN AND SOCIETY IN THE SOUTHERN AEGEAN EARLY BRONZE AGE. Tristan Carter VOLUMEI TEXT and BIBLIOGRAPHY i -ABSTRACT- This thesis considers the social context of Southern Aegean lithic technology during the fourth - third millennia B.C., focusing on the socio-political significance accorded the production and consumption of obsidian blades from the later Neolithic - Early Bronze Age. In Section One (Chapters One-Five) past work on Aegean obsidian is examined critically. Through drawing on data generated by recent surveys and excavations in the southern mainland, the Cyclades and Crete, it is argued that from the later Neolithic - EBII, the working of obsidian shifted from a community-wide basis to being located within a restricted number of settlements. These latter sites, due to their size and associated material culture, are suggested regional centres, acting as loci for skilled knappers and the dissemination of their products. This ability to influence or directly control such individuals is claimed to have played a role in the development of social inequality. The central part of the thesis, Section Two (Chapters Six-Nine) discusses the appearance of fine obsidian blades within the EBI Cycladic burial record, arguing that this new mode of consumption provides a context where one can see the reconceptualisation and political appropriation of lithic technology. -

Ancient Greek Civilization Part I

Ancient Greek Civilization Part I Jeremy McInerney, Ph.D. THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Jeremy McInerney, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Classical Studies University of Pennsylvania Jeremy McInerney received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1992. He was the Wheeler Fellow at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, and has excavated in Israel, at Corinth and on Crete. Since 1992 has been teaching Greek History at the University of Pennsylvania , where he held the Laura Jan Meyerson Term Chair in the Humanities from 1994 to 1998. He is currently an associate professor in the Department of Classical Studies and Chair of the Graduate Group in the Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World. Professor McInerney also serves on the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Professor McInerney's research interests include topography, epigraphy, and historiography. He has published articles in the American Journal of Archaeology, Hesperia, and California Studies in Classical Antiquity. In 1997 he was an invited participant at a colloquium on ethnicity in the ancient world, hosted by the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington. His book, The Folds of Parnassos: Land and Ethnicity in Ancient Phokis, is a study of state formation and ethnic identity in the Archaic and Classical periods, and it will be published by the University of Texas Press in 1999. © 1998 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership 1 Ancient Greek Civilization Table of Contents Professor Biography……………………………………………….1 -

The Greeks and the Bronze Age 1

9781405167321_4_001.qxd 23/10/2008 03:55PM Page 1 THE GREEKS AND THE BRONZE AGE 1 The Bronze Age (ca. 3000 to 1200 BC) marks for us the beginning of Greek Cycladic Civilization civilization. This chapter presents the arrival, in about 2000 BC, of Greek- speakers into the area now known as Greece and their encounter with the Minoan Civilization two non-Greek cultures that they found on their arrival, the civilizations known as Cycladic and Minoan. Cycladic civilization is notable for fine craftsmanship, The Greeks Speak Up especially its elegantly carved marble sculptures. The people of the Minoan civilization developed large-scale administrative centers based in grand palaces The Emergence of and introduced writing to the Aegean region. These and other features of Minoan civilization influenced greatly the form taken by Greek civilization in its earliest Mycenaean Civilization phase, the Mycenaean Period (ca. 1650 to 1200 BC). Unlike Cycladic and Minoan civilizations, which were based on the islands in the Aegean Sea, Greek The Character of civilization of the Mycenaean Period had its center in mainland Greece, where Mycenaean Civilization heavily fortified palaces were built. These palaces have provided archaeologists with abundant evidence of a warlike society ruled by powerful kings. Also The End of Mycenaean surviving from the Mycenaean Period are the earliest occurrences of writing in Civilization the Greek language, in the form of clay tablets using the script known as “Linear B.” This script, along with Mycenaean civilization as a whole, came to an end around 1200 BC for reasons that are not at all clear to historians. -

Which Was the Role of Cycladic Marble Figurines in Funerary Rituals?

Which was the role of Cycladic marble figurines in funerary rituals? Cycladic marble figurines are particular objects that for their style and shape already in ancient times have produced a great interest on them, still present after their rediscovery in the last century [1]. In Minoan Crete there was a production of imitations, while the originals are widespread in the whole Aegean area attesting their use as merchandise. The figurines were luxury objects in the same Cyclades; they were not very common, at least in marble [2]. However, they must have had a role in the society that produced them originally. Paradoxically, whereas we understand the significance of their presence in contexts outside Cyclades, as art objects and exchange goods, we have some difficulties to understand their meaning and purpose in the society, which produced them. The production of these figurines was certainly stimulated by the wide presence of marble in the area, and probably firstly were shaped marble figurines and then their possible imitations in wood or other perishable material. The emery from Naxos and the obsidian from Melos were extremely useful to work the marble, the first as an abrasive in powdered form, the other as cutting and incising tool. In the island of Thera there was also another abrasive agent, perhaps less used: pumice. The most important centres of production were in Paros and Naxos, where it is possible to find the best Cycladic marble. These two islands were particularly prosperous in Early Cycladic certainly also for the production of marble objects, not only figurines. The figurines appear for the first time in Early Cycladic period, precisely in the second stage of Early Cycladic I in a schematic form [3], an ancient moment of the Cycladic culture, while the first naturalistic ones appear in the third stage of the period.