Summer and Fall Movements of Narwhals (Monodon Monoceros) from Northeastern Baffin Island Towards Northern Davis Strait R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

The Scott Inlet – Buchan Gulf Oil Seeps: Actively Venting Petroleum Systems on the Northern Baffin Margin Offshore Nunavut, Canada

The Scott Inlet – Buchan Gulf Oil Seeps: Actively venting petroleum systems on the northern Baffin Margin offshore Nunavut, Canada Gordon. N. Oakey1, Phil N. Moir1*, Tom Brent2, Kate Dickie1, Chris Jauer1, Robbie Bennett1, Graham Williams1, Brian MacLean1, Paul Budkewitsch4**, Jim Haggart3, Lisel Currie2 1 Geological Survey of Canada (Atlantic), 1 Challenger Drive, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, B2Y 4A2 2 Geological Survey of Canada (Calgary) 3303-33rd St. NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada,T2L 2A7 3 Geological Survey of Canada (Pacific) 625 Robson St., Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6B 5J3 4 Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, 588 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0Y7 * retired ** now with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, PO Box 2000, Iqaluit, Canada, X0A 0H0 New analyses of legacy geophysical, geological and geochemical data have been integrated with modern multibeam bathymetry, RADARSAT imagery, and onshore geological mapping into a regional study of the petroleum system on the northern Baffin shelf offshore Nunavut. Industry seismic reflection profiles show that the Scott Inlet Graben is the southern end of an elongated basin (200-300 km by 25- 50 km wide) extending to the northwest along the Baffin Margin – now named Scott Inlet Basin – which contains up to 6 km of Mesozoic and Cenozoic strata. The seismic data define the outer edge of the Scott Inlet Basin; however, the landward edge is largely unknown and may locally outcrop onshore. Recent multibeam bathymetry data have been collected over the Scott Inlet Seep location as part of the ARCTICNET Research Program to study benthic habitats and geohazards in the Canadian Arctic waterways. -

NUNAVUT a 100 , 101 H Ackett R Iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C Lve Coal T Rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H Igh Lake , Izo K Lake M M G Resources Inc

150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 100°W 90°W 80°W 70°W 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W PROJECTS BY REGION Note: Bold project number and name signifies major or advancing project. AR CT KITIKMEOT REGION 8 I 0 C LEGEND ° O N umber P ro ject Operato r N O C C E Commodity Groupings ÉA AN B A SE M ET A LS Mineral Exploration, Mining and Geoscience N Base Metals Iron NUNAVUT A 100 , 101 H ackett R iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C lve Coal T rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H igh Lake , Izo k Lake M M G Resources Inc. I n B P Q ay q N Diamond Active Projects 2012 U paa Rare Earth Elements 104 Hood M M G Resources Inc. E inir utt Gold Uranium 0 50 100 200 300 S Q D IA M ON D S t D i a Active Mine Inactive Mine 160 Hammer Stornoway Diamond Corporation N H r Kilometres T t A S L E 161 Jericho M ine Shear Diamonds Ltd. S B s Bold project number and name signifies major I e Projection: Canada Lambert Conformal Conic, NAD 83 A r D or advancing project. GOLD IS a N H L ay N A 220, 221 B ack R iver (Geo rge Lake - 220, Go o se Lake - 221) Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. T dhild B É Au N L Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions E - a PRODUCED BY: B n N ) Committee Bay (Anuri-Raven - 222, Four Hills-Cop - 223, Inuk - E s E E A e ER t K CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply 222 - 226 North Country Gold Corp. -

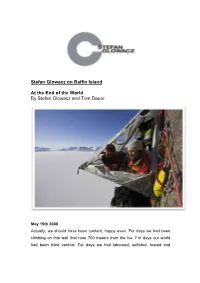

Stefan Glowacz on Baffin Island at the End of the World by Stefan Glowacz

Stefan Glowacz on Baffin Island At the End of the World By Stefan Glowacz and Tom Dauer May 15th 2008 Actually, we should have been content, happy even. For days we had been climbing on this wall that rose 700 meters from the ice. For days our world had been tilted vertical. For days we had laboured, suffered, feared and hoped. Until we had reached the highest point of the “Bastions”, a granite tower on the east coast of Baffin Island. The wind had lulled as we sat in the sun on the summit plateau. No human had been here before us. No one had yet looked out from here over the Buchan Gulf, over the Cambridge and the Quernbiter Fjord, and the Icy Arm. In the east, the flow edge marked the boundary between the ice pack and the open sea. And further out, beyond the Baffin Bay, lay Greenland. For more than an hour we enjoyed the view, the peace. Then we started to rappel down to base. Actually, a load should have fallen from our shoulders now. But Klaus Fengler, Holger Heuber, Mariusz Hoffmann, Robert Jasper and I knew very well that our lives would be depending on a shattering fundament. We had no more than 20 days to reach Clyde River, 350 kilometres away, each of us lugging a 75-kilogram pulka over melting ice. Four Weeks Earlier Looking out the window of the small Twin Otter, I felt like staring into a giant freezer and I realized that you can’t only feel the cold, but you can also see it. -

Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967 Ives, Jack D. University of Calgary Press Ives, J.D. "Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967." Canadian history and environment series; no. 18. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51093 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca BAFFIN ISLAND: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961–1967 by Jack D. Ives ISBN 978-1-55238-830-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

17 September 2015

MARINE MAMMAL AERIAL SURVEYS IN ECLIPSE SOUND, MILNE INLET AND POND INLET, 1 AUGUST – 17 SEPTEMBER 2015 by for LGL DRAFT Report FA0059-2 15 March 2016 MARINE MAMMAL AERIAL SURVEYS IN ECLIPSE SOUND, MILNE INLET AND POND INLET, 1 AUGUST – 17 SEPTEMBER 2015 by Tannis A. Thomas, Scott Raborn, Robert E. Elliott and Valerie D. Moulton LGL Limited, environmental research associates P.O. Box 280, King City, ON L7B 1A6 [email protected] for Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation 2275 Upper Middle Road East, Suite 300 Oakville, ON L6H 0C3 LGL DRAFT Report FA0059-2 15 March 2016 Suggested format for citation: Thomas, T.A., S. Raborn, R.E. Elliott and V.D. Moulton. 2016. Marine mammal aerial surveys in Eclipse Sound, Milne Inlet and Pond Inlet, 1 August – 17 September 2015. LGL Draft Report No. FA0059-2. Prepared by LGL Limited, King City, ON for Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation, Oakville, ON. 85 p. + appendices. Page ii Disclaimer This technical report is considered a draft and is subject to review and input from the Marine Environment Working Group (MEWG) established for the Mary River Project. Page iii This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of Approach and Key Findings .................................................................................... xii Extensive Aerial Surveys ................................................................................................... xiii Photographic Surveys ........................................................................................................ -

Atlantic Walrus Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 23 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Richard, P. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-23 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the status report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Andrew Trites, Co-chair, COSEWIC Marine Mammals Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation du morse de l'Atlantique (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

ARCTIC CHANGE 2014 8-12 December - Shaw Centre - Ottawa, Canada

ARCTIC CHANGE 2014 8-12 December - Shaw Centre - Ottawa, Canada Oral Presentation Abstracts Arctic Change 2014 Oral Presentation Abstracts ORAL PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS TEMPORAL TREND ASSESSMENT OF CIRCULATING conducted when possible. Results: Maternal levels of Hg and MERCURY AND PCB 153 CONCENTRATIONS AMONG PCB 153 significantly decreased between 1992 and 2013. NUNAVIMMIUT PREGNANT WOMEN (1992-2013) Overall, concentrations of Hg and PCB 153 among pregnant women decreased respectively by 57% and 77% over the last Adamou, Therese Yero (12) ([email protected]), M. Riva (12), E. Dewailly (12), S. Dery (3), G. Muckle (12), R. two decades. In 2013, concentrations of Hg and PCB 153 were Dallaire (12), EA. Laouan Sidi (1) and P. Ayotte (1,2,4) respectively 5.2 µg/L and 40.36 µg/kg plasma lipids (geometric means). Discussion: Our results suggest a significant decrease (1) Axe santé des populations et pratiques optimales en santé, of Hg and PCB 153 maternal levels from 1992 to 2013. Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Geometric mean concentrations of Hg and PCB 153 measured Québec, Québec,Québec, G1V 2M2 in 2013 were below Health Canada guidelines. The decline (2) Université Laval, Québec, Québec, G1V 0A6 observed could be related to measures implemented at regional, (3) Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services, Kuujjuaq, Québec national and international levels to reduce environmental (4) Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (INSPQ), pollution by mercury and PCB and/or a significant decrease Québec, G1V 5B3 of seafood consumption by pregnant women. These results have to be interpreted with caution. -

BAFFIN ISLAND 1953: TAGEBUCH EINER POLAR- Rale Du Nouveau Québec and the Commission Scolaire Du EXPEDITION

REVIEWS • 253 HBC agents gave no credit. During this period the outside The final section of the book deals with Qumaq’s reflec- world intervened with the news of the war. In addition, tions from the vantage of age—changes, importance of the slow move to Puvirnituq and other settlements began, hunting and fishing, the divisions over James Bay, his dif- and prefabricated houses replaced the traditional tents and ficulties as he aged and experienced illnesses, the friends igloos. Employment at the trading post and the sale of stone who helped him, and his family, who had figured through- sculptures began to alter Inuit lives. out the narrative. Part three documents significant changes to Inuit life As befitting an individual with little formal school- from 1953 to the late 1960s. Central to these changes was ing, yet writing in syllabics, the style is relatively simple the introduction of federal aid: old age pensions, disabil- and straightforward. Besides the observations on changes ity allowances, and family allowances. The Bay began to in lifestyle, a strength of the book is the discussion on the purchase Inuit sculptures, though the author notes that each evolution of autonomy, whether in co-operatives, villages, manager had a different concept of their value (p. 81). Their or region, and especially the opposition to the James Bay attitude changed with the arrival of manager Peter Mur- agreement. In translating this work, Louis-Jacques Dorais doch in 1955. Under his management, there was a certain has done a great service by bringing Qumaq’s story to a stability, even though the Bay would still not allow Inuit to wider readership. -

NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas Cultural Heritage and Interpretative

NTI IIBA for Phase I: Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report Cultural Heritage Area: Dewey Soper and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This report is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Report Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Names of places that do not have official names will appear as they are found in the source documents. Contents Maps and Photographs ................................................................................................................... 2 Information Tables .......................................................................................................................... 2 Section -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Canadian Arctic Tide Measurement Techniques and Results

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LXIII (2), July 1986 CANADIAN ARCTIC TIDE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES AND RESULTS by B.J. TAIT, S.T. GRANT, D. St.-JACQUES and F. STEPHENSON (*) ABSTRACT About 10 years ago the Canadian Hydrographic Service recognized the need for a planned approach to completing tide and current surveys of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in order to meet the requirements of marine shipping and construction industries as well as the needs of environmental studies related to resource development. Therefore, a program of tidal surveys was begun which has resulted in a data base of tidal records covering most of the Archipelago. In this paper the problems faced by tidal surveyors and others working in the harsh Arctic environment are described and the variety of equipment and techniques developed for short, medium and long-term deployments are reported. The tidal characteris tics throughout the Archipelago, determined primarily from these surveys, are briefly summarized. It was also recognized that there would be a need for real time tidal data by engineers, surveyors and mariners. Since the existing permanent tide gauges in the Arctic do not have this capability, a project was started in the early 1980’s to develop and construct a new permanent gauging system. The first of these gauges was constructed during the summer of 1985 and is described. INTRODUCTION The Canadian Arctic Archipelago shown in Figure 1 is a large group of islands north of the mainland of Canada bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea, on the north by the Arctic Ocean and on the east by Davis Strait, Baffin Bay and Greenland and split through the middle by Parry Channel which constitutes most of the famous North West Passage.