Khanna - Tehranian Comments.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

A Remix Manifesto

An Educational Guide About The Film In RiP: A remix manifesto, web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers. The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash‐up musician topping the charts with his sample‐based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil, and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow also come along for the ride. This is a participatory media experiment from day one, in which Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org for anyone to remix. This movie‐as‐mash‐up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle. Which side of the ideas war are you on? About The Guide While the film is best viewed in its entirety, the chapters have been summarized, and relevant discussion questions are provided for each. Many questions specifically relate to music or media studies but some are more general in nature. General questions may still be relevant to the arts, but cross over to social studies, law and current events. Selected resources are included at the end of the guide to help students with further research, and as references for material covered in the documentary. This guide was written and compiled by Adam Hodgins, a teacher of Music and Technology at Selwyn House School in Montreal, Quebec. -

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and Works in Brooklyn NY

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and works in Brooklyn NY Selected Multimedia Fabrications 2019: Kunsthalle Basel, Dora Budor: ‘The Preserving Machine’, Basel, Switzerland ● Raspberry Pi & Arduino microcontroller programming, biomechanical flying bird controlled via bluetooth and custom javascript / node.js code. Flight pattern based on data taken from Beethoven's 9th symphony. Musical data was parsed with Ableton Live and a custom Max/MSP patch, data translated into Javascript. Nike, ‘Nike Soho: Department of Unimaginable’, New York, NY ● Kinetic sculpture commission for mixed media installation and window display at Nike’s 5-story Soho retail location. 3D printed components, Arduino microcontroller programming, LEDs, GPU liquid cooling system pumps and fans, UV sensitive paint and filament, reclaimed e-waste. Esther Klein Gallery, Laura Splan: ‘Remote Entanglements’, ‘Contested Territories’, Philadelphia, PA ● Designed, programmed, and fabricated custom networked sculptures. Modified fan, wireless Raspberry Pi control, adjusting wind speed in real time to data from a biological laboratory. Twitter actuated lab mixer, IOT microcontroller, networked control. Wonderspaces Gallery, Foo/Skou: ‘Harmony of Spheres’, San Diego, CA ● Prototyping, development and fabrication of an interactive light and sound sculpture. Eighty-one wooden spheres coated in touch-sensitive conductive paint triggering eighty-one audio loops of choral vocalists and eighty-one LED spotlights. Interactive spatial playback on eighteen separate audio channels. Arduino microcontroller programming, capacitive touch sensor, polyphonic audio module, programmable LEDs. Amaro Montenegro, ‘Zest’s Lab’, Brooklyn Bar Convention, Brooklyn, NY ● Interactive sculpture commission for immersive theater performance / experiential marketing campaign. Mixed media, custom audio synthesizer, lighting, peristaltic liquid pumps for elaborate cocktail mixing device. -

The Hood Internet Mixes It Up

CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) DJZ (http://www.djz.com/) CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW INTERVIEW: THE HOOD INTERNET MIXES IT UP Kim Reyes • SEP 11, 2013 Tweet 1 Aaron Brink and Steve Reidell decided to break out into the mash-up music scene under the moniker The Hood Internet (http://www.djz.com/tag/the-hood- internet) in a time when the genre was hot. Brink and Reidell, known by their DJ names ABX and STV SLV, have been releasing free mash-up songs and mixes on their website since 2007. What began as an internet project has transformed overtime to incorporate live DJ sets and a studio album of original tracks. Before taking the stage at the San Francisco venue The Independent on August 17, Reidell briefly explained the history of how The Hood Internet came to be. “ABX and I had a history of experimenting with looped-based software, just kind of making fun beats out of songs for our friends to rap on. The internet at the time seemed to be really receptive to mashups and I think we wanted to approach them with a little different twist.” In order to set themselves apart from other mash-up peers like Girl Talk (http://illegal-art.net/girltalk/), The Hood Internet decided to curate music by fusing rap and hip-hop with indie and electronic music. These songs were not necessarily chosen for their mainstream popularity, but were tracks chosen from Brink and Reidell’s own personal library of music. -

Sampling the Circuits: the Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement As a Result of Music Sampling

Washington University Law Review Volume 89 Issue 5 2012 Sampling the Circuits: The Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement as a Result of Music Sampling John S. Pelletier Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation John S. Pelletier, Sampling the Circuits: The Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement as a Result of Music Sampling, 89 WASH. U. L. REV. 1135 (2012). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol89/iss5/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAMPLING THE CIRCUITS: THE CASE FOR A NEW COMPREHENSIVE SCHEME FOR DETERMINING COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT AS A RESULT OF MUSIC SAMPLING INTRODUCTION Music sampling continues to be the linchpin of a variety of musical styles including rap, hip-hop, house, and dance music, and has even become prevalent in rock music.1 The practice of sampling involves taking pre-existing sound recordings and using portions of those recordings as elements in a new musical composition.2 The amount of the work sampled can range from taking the entire ―hook‖ or chorus/refrain from a musical composition to smaller elements, such as a riff or even one or two notes or words.3 Music sampling, as it pertains to copyright law and copyright licensing, is a real and current issue. -

Man Depends on Former Wife for Everyday Needs

6A RECORDS/A DVICE TEXARKANA GAZETTE ✯ MONDAY, JULY 19, 2021 5-DAY LOCAL WEATHER FORECAST DEATHS Man depends on former TODAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY EUGENE CROCKETT JR. Eugene “Ollie” Crockett Jr., 69, of Ogden, AR, died Wednesday, July 14, 2021, in wife for everyday needs Ogden, AR. High-Upper 80s High-Upper 80s Mr. Dear Abby: I have been with my boy- but not yet. Low-Near 70 Low-Lower 70s Crockett was friend, “John,” for a year and a half. He had When people see me do things that are born May been divorced for two years after a 20-year considered hard work, they presume I need 19, 1952, in marriage when we got together. He told help. For instance, today I bought 30 cement THURSDAY FRIDAY Dierks, AR. He was a Car me he and his ex, “Jessica,” blocks to start building a wall. Several men Detailer. He Dear Abby were still good friends. I asked if I needed help. I refused politely as was preced- thought it was OK since I always do, saying they were thoughtful to Jeanne Phillips High-Upper 80s ed in death they were co-parenting offer but I didn’t need help. They replied, by his par- Low-Lower 70s High-Lower 90s High-Lower 90s their kid. I have children of “No problem.” Low-Lower 70s Low-Mid-70s ents, Bernice my own, and I understand. A short time later it started raining. A and Eugene Crockett Sr.; one I gave up everything and woman walked by carrying an umbrella sister, Bertha Lee Crockett; moved two hours away to and offered to help, and I responded just thunderstorms. -

Three Solitudes and a DJ: a Mashed-Up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-26-2013 12:00 AM Three Solitudes and a DJ: A Mashed-up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm Anthony B. Cushing The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Norma Coates The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Anthony B. Cushing 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Cushing, Anthony B., "Three Solitudes and a DJ: A Mashed-up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1229. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1229 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THREE SOLITUDES AND A DJ: A MASHED-UP STUDY OF COUNTERPOINT IN A DIGITAL REALM (Thesis format: Monograph) by Anthony B. Cushing Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Anthony Cushing 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation is primarily concerned with developing an understanding of how the use of pre-recorded digital audio shapes and augments conventional notions of counterpoint. It outlines a theoretical framework for analyzing the contrapuntal elements in electronically and digitally composed musics, specifically music mashups, and Glenn Gould’s Solitude Trilogy ‘contrapuntal radio’ works. -

The Funky Diaspora

The Funky Diaspora: The Diffusion of Soul and Funk Music across The Caribbean and Latin America Thomas Fawcett XXVII Annual ILLASA Student Conference Feb. 1-3, 2007 Introduction In 1972, a British band made up of nine West Indian immigrants recorded a funk song infused with Caribbean percussion called “The Message.” The band was Cymande, whose members were born in Jamaica, Guyana, and St. Vincent before moving to England between 1958 and 1970.1 In 1973, a year after Cymande recorded “The Message,” the song was reworked by a Panamanian funk band called Los Fabulosos Festivales. The Festivales titled their fuzzed-out, guitar-heavy version “El Mensaje.” A year later the song was covered again, this time slowed down to a crawl and set to a reggae beat and performed by Jamaican singer Tinga Stewart. This example places soul and funk music in a global context and shows that songs were remade, reworked and reinvented across the African diaspora. It also raises issues of migration, language and the power of music to connect distinct communities of the African diaspora. Soul and funk music of the 1960s and 1970s is widely seen as belonging strictly in a U.S. context. This paper will argue that soul and funk music was actually a transnational and multilingual phenomenon that disseminated across Latin America, the Caribbean and beyond. Soul and funk was copied and reinvented in a wide array of Latin American and Caribbean countries including Brazil, Panama, Jamaica, Belize, Peru and the Bahamas. This paper will focus on the music of the U.S., Brazil, Panama and Jamaica while highlighting the political consciousness of soul and funk music. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Biz Markie Goin' Off Mp3, Flac, Wma

Biz Markie Goin' Off mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Goin' Off Country: US Released: 1988 MP3 version RAR size: 1698 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1846 mb WMA version RAR size: 1926 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 967 Other Formats: TTA XM VQF ASF MP3 DTS MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Pickin' Boogers 4:42 A2 Albee Square Mall 4:43 A3 Biz Is Goin' Off 4:50 A4 Return Of The Biz Dance 3:59 A5 Vapors 4:33 Make The Music With Your Mouth, Biz B1 4:56 Remix – Marley Marl Biz Dance (Part One) B2 3:38 Remix – Marley Marl Nobody Beats The Biz B3 5:42 Remix – Marley Marl B4 This Is Something For The Radio 5:14 B5 Cool V's Tribute To Scratching 3:07 Credits Arranged By – Biz Markie Design, Photography – George Du Bose* Lyrics By – Big Daddy Kane (tracks: A1 to A5) Producer, Mixed By – Marley Marl Vocals [Uncredited] – TJ Swan (tracks: A2, B1, B3) Written-By – Biz Markie, Marley Marl Notes Distributed by Warner Bros. Records, Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 7599-25675-4 1 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 1-25675, 9 Biz Goin' Off (LP, Cold Chillin', Cold 1-25675, 9 US 1988 25675-1 Markie Album) Chillin' 25675-1 PCD-23797 Biz Goin' Off (CD, CAK PCD-23797 Japan 2006 R-0650672MT Markie Album, RE) Entertainment R-0650672MT Biz Goin' Off (LP, 925 675-1 Cold Chillin' 925 675-1 France 1988 Markie Album) Biz Goin' Off (CD, 9 25675-2 Cold Chillin' 9 25675-2 US 1988 Markie Album, Lon) Biz Goin' Off (CD, CCCD 9001 Cold Chillin' CCCD 9001 US 1995 Markie Album, RE) Related Music albums to Goin' Off by Biz Markie Big Daddy Kane - Long Live The Kane Da Youngsta's - Hip Hop Ride / No Mercy Monie Love - In A Word Or 2 Marley Marl - In Control Volume 1 Spoonie Gee - The Godfather Bob Marley & The Wailers - The Complete Bob Marley & The Wailers 1967-1972 Part II Marley Marl - Hip Hop Dictionary Vol. -

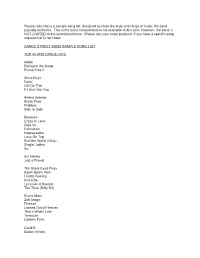

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. DANCE STREET BAND SAMPLE SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Rolling in the Deep Rumor Has It Alicia Keys Fallin’ Girl On Fire If I Ain’t Got You Ariana Grande Break Free Problem Side to Side Beyonce Crazy In Love Deja Vu Formation Irreplaceable Love On Top Run the World (Girls) Single Ladies Xo Biz Markie Just a Friend The Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow I Gotta Feeling Imma Be Let’s Get It Started The Time (Dirty Bit) Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Locked Out of Heaven That’s What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jespen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Feel So Close Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don't Let Me Down Chance the Rapper No Problem Chris Brown Look at Me Now Christina Perri A Thousand Years Christina Aguilera, Lil’Kim, Mya &Pink Lady Marmalade Clean Bandit Rather Be Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky One More Time David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Sorry Not Sorry Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Echosmith Cool Kids Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Fun. -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities.