ACCORD COI Compilation Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

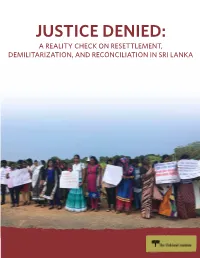

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 ELECTION COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA 2017-2020 Department of Government Printing STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) of the Election Commission of Sri Lanka for 2017-2020 “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives... The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will, shall be expressed in periodic ndenineeetinieniendeend shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” Article 21, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020 I Foreword By the Chairman and the Members of the Commission Mahinda Deshapriya N. J. Abeysekere, PC Prof. S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole Chairman Member Member The Soulbury Commission was appointed in 1944 by the British Government in response to strong inteeneeinetefittetetenteineentte population in the governance of the Island, to make recommendations for constitutional reform. The Soulbury Commission recommended, interalia, legislation to provide for the registration of voters and for the conduct of Parliamentary elections, and the Ceylon (Parliamentary Election) Order of the Council, 1946 was enacted on 26th September 1946. The Local Authorities Elections Ordinance was introduced in 1946 to provide for the conduct of elections to Local bodies. The Department of Parliamentary Elections functioned under a Commissioner to register voters and to conduct Parliamentary elections and the Department of Local Government Elections functioned under a Commissioner to conduct Local Government elections. The “Department of Elections” was established on 01st of October 1955 amalgamating the Department of Parliamentary Elections and the Department of Local Government Elections. -

Sri Lanka's Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire

Sri Lanka’s Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire Asia Report N°253 | 13 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Northern Province Elections and the Future of Devolution ............................................ 2 A. Implementing the Thirteenth Amendment? ............................................................. 3 B. Northern Militarisation and Pre-Election Violations ................................................ 4 C. The Challenges of Victory .......................................................................................... 6 1. Internal TNA discontent ...................................................................................... 6 2. Sinhalese fears and charges of separatism ........................................................... 8 3. The TNA’s Tamil nationalist critics ...................................................................... 9 D. The Legal and Constitutional Battleground .............................................................. 12 E. A Short- -

YS% ,Xldfő Udkj Ysńlď

Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: Aug 2015 to Aug 2016 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre- 2016 Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: August 17, 2015 - August 17, 2016 © INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre, 2016 Colombo Sri Lanka Cover page photos: Upper photo: Protestors demanding the release of political prisoners, 8th August 2016, Jaffna, Sri Lanka. © Tamil Guardian http://www.tamilguardian.com/content/tamils-demand-release-political-prisoners Below photo: People of Panama refuse to accede to a government order to vacate their traditional land. They were forcefully evicted from lands by military since 2010. Protest was held on 21st of June, 2016, Panama, Sri Lanka. © Sri Lankan Mirror http://www.srilankamirror.com/news/item/11216-panama-people-refuse-to-leave-their-land INFORM was established in 1990 to monitor and document human rights situation in Sri Lanka, especially in the context of the ethnic conflict and war, and to report on the situation through written and oral interventions at the local, national and international level. INFORM also focused on working with other communities whose rights were frequently and systematically violated. Presently, INFORM is focusing on election monitoring, freedom expression and human rights defenders. INFORM is based in Colombo Sri Lanka, and works closely with local activists, groups and networks as well as regional (Asian) and international human rights networks. 1 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre www.ihrdc.wordpress.com [email protected] Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: Aug 2015 to Aug 2016 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre- 2016 Contents Introduction and acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 3 List of Writers .............................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

Transparency International Sri Lanka V. Presidential Secretariat

At the Right to Information Commission of Sri Lanka Transparency International Sri Lanka v. Presidential Secretariat RTICAppeal/06/2017 Appeals heard as part of the meetings of the Commission on 12.06.2017 (RTIC Appeal/05/2017); 19.06.2017( RTIC Appeal/06/2017); 08.08.2017, 25.09.2017, 06.11.2017; 08.01.2018; 23.02.2018 (delivery of Order on Jurisdiction);24.04.2018 (amendment of papers by Appellant);26.06.2018; 04.09.2018 and 30.10.2018 Record of Proceedings and Order On Merits delivered on 4th December 2018 Chairperson: Mr. Mahinda Gammampila Commission Members: Ms. Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena Mr. S.G. Punchihewa Dr. Selvy Thiruchandran Justice Rohini Walgama Appellant: Transparency International Sri Lanka Notice issued to: Secretary to the President, Presidential Secretariat Information Request filed to Presidential Secretariat on 03.02.2017 Response by Information Officer on 06.03.2017 Appeal filed to Designated Officer on 10.03.2017 Response by Designated Officer on 20.03.2017 Appeal filed to RTI Commission on 19.05.2017 Written Submissions/Further Written Submissions filed on; (By the Appellant: 25.07.2017, 23.10.2017, 04.01.2018; 08.01.2018; 25. 06. 2018; 25.10.2018; 23.11.2018) (By the Respondent: Presidential Secretariat: 31.07.2017, 08.09.2017; 03.01.2018; 04.09.2018) Appearance/ Represented by: Counsel for the Appellant (appearing at various times during the hearing of the appeal): Mr. Gehan Goonetilleka, AAL Ms Sankhitha Guneratne, AAL 1 At the Right to Information Commission of Sri Lanka Counsel for the PA (Presidential Secretariat): Mr. -

April - June 2015

Issue No. 147 April - June 2015 National Anthem sung in Tamil The national anthem was sung in Tamil in the presence of President Maithripala Sirisena, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga at an event, where the lands taken over by the mili- tary to establish a High Security Zone were handed back to the legitimate owners at Valalaai, Valikamam East on 23rr March. Human Rights Review : April - June Institute of Human Rights 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial 03 The New government ♦ Extracts from an article by Faizer Shaheid - PTA ALWAYS DISCRIMINAED 06 ♦ Four cheers for judicial independence 07 ♦ Presidential powers and the craving to be slaves 08 ♦ 19th Amendment: Why this indecent haste? 09 ♦ Up to president to act on COPE report: DEW 10 ♦ Arjuna Mahendran's culpability proved! ♦ Sampanthan welcomes 19A 11 ♦ The politics, economics and fundamental rights of grand corruption in Sri Lanka ♦ Sobhitha Thera interviewed by Subashini Gunaratne 12 Situation in the North & East ♦ Return of the denied land 13 ♦ Now the war is over, where do they go? ♦ Northern Spring Programme... 86 villages still powerless 14 ♦ Protest in Mullaitivu against confiscated land ♦ Special Court to hear case: MS 15 ♦ Filling the vacuum Situation in the Hill Country ♦ Koslanda Tragedy turns calamity 16 Media Freedom ♦ Tamil journalists’ woes continue 16 Sri Lanka In the International scene ♦ US PRESSES GOVT....NOTIFY FAMILIES IMMEDIATELY OF LIVING POLITICAL 17 PRISONERS... ♦ TNA wants action on war crimes ♦ Excerpts -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

New Faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr

8 THE SUNDAY TIMES ELECTIONS Sunday April 18, 2010 New faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr. Ramesh Pathirana UPFA Nimal Senarath UPFA Born in 1960 Born in 1969. S. Udayan (Silvestri Wijesinghe Doctor by profession. A medical doctor by profes- alantin alias Uthayan) Born in 1969. R. Duminda Silva Former DMO of the sion. Born in 1972. Educated at Kirindigalla MV Born 1974. Negombo Hospital. Son of former Education Studied at Delft Maha and Ibbagamuwa MV. Businessman. Served for more than 10 Minister Richard Pathirana. Vidyalaya. Profession – Businessman. Studied at St. Peter’s Col- years at the Children’s Health Studied at Richmond Col- Joined EPDP in 1992. UNP Organiser of Rambo- lege, Colombo. Care Bureau of the Health. lege, Galle. Former deputy Chairman of dagalla in 2006. Elected to the Western Pro- Chief Organiser of Akmeemana. the Karaveddy Pradeshiya Sabha. Elected to the North Western Provincial Coun- vincial Council in 2009 on the Executive Committee Member of the Cey-Nor cil in 2009. UPFA ticket and topped the preferential votes Fishing Net Factory. Father of two. list. Wasantha Senanayake SLFP Chief Organiser for Kolonnawa. Barister of Law. Studied at Sajin Vaas Gunawardene Awarded Deshabimana Deshashakthi Janaran- S. Thomas’ Prep. Graduated Born in 1973. WANNI PUTTALAM jana from the National Peace Association. Univ. Buckingham LLB. Prominent business Great grandson of Ceylon’s personality. UPFA UPFA first Prime Minister D. S. SLFP Galle District Senanayake and F.R. Organiser. Noor Mohommed Farook Victory Anthony Perera Thilanga Sumathipala Senanayake. President’s Coordinating Born in 1975. Native of Born in 1949. Born 1964 Secretary. -

Report of the Secretary-General's Panel Of

REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL’S PANEL OF EXPERTS ON ACCOUNTABILITY IN SRI LANKA 31 March 2011 REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL’S PANEL OF EXPERTS ON ACCOUNTABILITY IN SRI LANKA Executive Summary On 22 June 2010, the Secretary-General announced the appointment of a Panel of Experts to advise him on the implementation of the joint commitment included in the statement issued by the President of Sri Lanka and the Secretary-General at the conclusion of the Secretary-General’s visit to Sri Lanka on 23 March 2009. In the Joint Statement, the Secretary-General “underlined the importance of an accountability process”, and the Government of Sri Lanka agreed that it “will take measures to address those grievances”. The Panel’s mandate is to advise the Secretary- General regarding the modalities, applicable international standards and comparative experience relevant to an accountability process, having regard to the nature and scope of alleged violations of international humanitarian and human rights law during the final stages of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka. The Secretary-General appointed as members of the Panel Marzuki Darusman (Indonesia), Chair; Steven Ratner (United States); and Yasmin Sooka (South Africa). The Panel formally commenced its work on 16 September 2010 and was assisted throughout by a secretariat. Framework for the Panel’s work In order to understand the accountability obligations arising from the last stages of the war, the Panel undertook an assessment of the “nature and scope of alleged violations” as required by its Terms of Reference. The Panel’s mandate however does not extend to fact- finding or investigation.