Inflectional Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

287374128.Pdf

This is the accepted manuscript of the article, which has been published in Kittilä S., Västi K., Ylikoski J. (eds.) Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles. Typological Studies in Language, 99. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2011. ISBN 978-90-272-0680-0. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.99 Is there a future for the Finnish comitative? Arguments against the putative synonymy of the comitative case -ine and the postposition kanssa Maija Sirola-Belliard University of Tampere 1. Introduction The core meaning of the comitative is Accompaniment, although cross- linguistically the same form can also be used for encoding Instrument or Possession, for example. The comitative is prototypically used to combine two nominal phrases which represent two human participants in a situation where one is accompanying the other. This relationship is not symmetrical: one of the participants in the situation is the main actor, so called accompanee, while the other, the companion, is more marginal and can be involved in the action only indirectly, i.e. through the accompanee. (Stolz et al. 2006: 5; 2009: 602f.) Across languages, Accompaniment can be expressed by adpositions, case affixes and serial constructions, among other means (Stolz et al. 2009: 602f.). In Finnish, the principal means are an inflectional case and several postpositions governing the genitive case. The comitative case marker is -ine, which, when 1 attached to a noun, is obligatorily followed by a possessive suffix that refers (in most cases) to the accompanee. The case marker is formally a plural since the plural marker -i- has been grammaticalized as a part of the affix. -

Study Guide to Exam 1

LIN 3460 Spring 2009 Study Guide to Exam 1 Topics and skills we’ve covered: • Characteristics of the natural human language system (generality, creativity, inaccessibility, universality) • Language universals and their types (absolute universals vs. tendencies) • The morpheme as thing/process • Morphological concepts • Types of morphemes: bound vs. free • Kinds of affixes (prefix, suffix, infix, simulfix) • Portmanteau morpheme • Zero morpheme • Blends • Morphological processes (affixation, reduplication, replacive, subtractive) • Morphological terminology (root, stem, affix, etc.) • Grammatical vs. lexical morphemes • Derivation vs. inflection • Identifying morphemes • Word formation rules (morphotactics) • Translating glossed examples The relevant readings in DOL are Ch. 1 (esp. 1-10) Ch. 5 (230-232, 252-271) (identifying morphemes, morphotactics, inflection and derivation) The exam consists of two parts. Here are the instructions from the two parts: I. Morphological Analysis Give a lexicon and grammar that completely describes each of the two sets of data that follow. Your answer should contain a lexicon of lexical entries. Model them on the ones given below and ones from class problems. Your answer should also contain word formation rules. Again model them on the ones given below and ones from class problems. Include any commentary that you feel would be helpful in making your answer understandable. II. Short Answer Answer the following questions (you will have to choose 5 out of 7). Samples of exam questions follow. Note that the exam is not short. You will need to know the material well to finish in good time. LIN 3460 Spring 2009 Sample exam problems I. Morphological Analysis Give a lexicon and grammar that completely describes each of the three sets of data that follow. -

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras To cite this version: Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras. Romani Syntactic Typology. Yaron Matras; Anton Tenser. The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics, Springer, pp.187-227, 2020, 978-3-030-28104- 5. 10.1007/978-3-030-28105-2_7. halshs-02965238 HAL Id: halshs-02965238 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02965238 Submitted on 13 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romani syntactic typology Evangelia Adamou and Yaron Matras 1. State of the art This chapter presents an overview of the principal syntactic-typological features of Romani dialects. It draws on the discussion in Matras (2002, chapter 7) while taking into consideration more recent studies. In particular, we draw on the wealth of morpho- syntactic data that have since become available via the Romani Morpho-Syntax (RMS) database.1 The RMS data are based on responses to the Romani Morpho-Syntax questionnaire recorded from Romani speaking communities across Europe and beyond. We try to take into account a representative sample. We also take into consideration data from free-speech recordings available in the RMS database and the Pangloss Collection. -

Polyvalent Case, Geometric Hierarchies, and Split Ergativity

[For Jackie Bunting, Sapna Desai, Robert Peachey, Chris Straughn, and Zuzana Tomkova (eds.), (2006) Proceedings of the 42nd annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, Chicago, Ill.] Polyvalent case, geometric hierarchies, and split ergativity JASON MERCHANT University of Chicago Prominence hierarchy effects such as the animacy hierarchy and definiteness hierarchy have been a puzzle for formal treatments of case since they were first described systematically in Silverstein 1976. Recently, these effects have received more sustained attention from generative linguists, who have sought to capture them in treatments grounded in well-understood mechanisms for case assignment cross-linguistically. These efforts have taken two broad directions. In the first, Aissen 1999, 2003 has integrated the effects elegantly into a competition model of grammar using OT formalisms, where iconicity effects emerge from constraint conjunctions between constraints on fixed universal hierarchies (definiteness, animacy, person, grammatical role) and a constraint banning overt morphological expression of case. The second direction grows out of the work of Jelinek and Diesing, and is found most articulated in Jelinek 1993, Jelinek and Carnie 2003, and Carnie 2005. This work takes as its starting point the observation that word order is sometimes correlated with the hierarchies as well, and works backwards from that to conclusions about phrase structure geometries. In this paper, I propose a particular implementation of this latter direction, and explore its consequences for our understanding of the nature of case assignment. If hierarchy effects are due to positional differences in phrase structures, then, I argue, the attested cross-linguistic differences fall most naturally out if the grammars of these languages countenance polyvalent case—that is, assignment of more than one case value to a single nominal phrase. -

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

Introduction to Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles: ALAOTSIKKO

1 Introduction to Case, animacy and semantic roles Please cite this paper as: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi and Jussi Ylikoski. (2011) Introduction to case, animacy and semantic roles. In: Kittilä, Seppo, Katja Västi & Jussi Ylikoski (Eds.), Case, Animacy and Semantic Roles, 1-26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Seppo Kittilä Katja Västi Jussi Ylikoski University of Helsinki University of Oulu University of Helsinki University of Helsinki 1. Introduction Case, animacy and semantic roles and different combinations thereof have been the topic of numerous studies in linguistics (see e.g. Næss 2003; Kittilä 2008; de Hoop & de Swart 2008 among numerous others). The current volume adds to this list. The focus of the chapters in this volume lies on the effects that animacy has on the use and interpretation of cases and semantic roles. Each of the three concepts discussed in this volume can also be seen as somewhat problematic and not always easy to define. First, as noted by Butt (2006: 1), we still have not reached a full consensus on what case is and how it differs, for example, from 2 the closely related concept of adpositions. Second, animacy, as the label is used in linguistics, does not fully correspond to a layperson’s concept of animacy, which is probably rather biology-based (see e.g. Yamamoto 1999 for a discussion of the concept of animacy). The label can therefore, if desired, be seen as a misnomer. Lastly, semantic roles can be considered one of the most notorious labels in linguistics, as has been recently discussed by Newmeyer (2010). There is still no full consensus on how the concept of semantic roles is best defined and what would be the correct or necessary number of semantic roles necessary for a full description of languages. -

Grammatical Categories and Word Classes Pdf

Grammatical categories and word classes pdf Continue 목차 qualities and phrases about qualities and dalakhin scared qualities are afraid of both hard long only the same, identical adjectives and common adverbs phrases and common adverbs comparison and believe adverbs class sayings of place and movement outside away and away from returning inside outside close up the shifts of time and frequency easily confused the words above or more? Across, over or through? Advice or advice? Affect or affect? Every mother of every? Every mother wholly? Allow, allow or allow? Almost or almost? Single, lonely, alone? Along or side by side? Already, still or yet? Also, as well as or too? Alternative (ly), alternative (ly) though or though? Everything or together? Amount, number or quantity? Any more or any more? Anyone, anyone or anything? Apart from or with the exception? arise or rise? About or round? Stir or provoke? As or like? Because or since then? When or when? Did she go or she?. Start or start? Next to or next? Between or between? Born or endured? Bring, take and bring can, can or may? Classic or classic? Come or go? Looking or looking? Make up, compose or compose? Content or content? Different from or different from or different from? Do you do or make? Down or down or down? During or for? All or all? East or East; North or North? Economic or economic? Efficient or effective? Older, older or older, older? The end or the end? Private or specific? Every one or everybody? Except or with exception? Expect, hope or wait? An experience or an experiment? Fall or fall? Far or far? Farther, farther or farther, farther? Farther (but not farther) fast, fast or fast? Fell or did you feel? Female or female; male or male? Finally, finally, finally or finally? First, first or at first? Fit or suit? Next or next? For mother since then? Forget or leave? Full or full? Funny or funny? Do you go or go? Grateful or thankful? Listen or listen (to)? High or long? Historical or historical? A house or a house? How is he...? Or what is .. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

A Morpho-Phonemic Analysis on Sasak Affixation

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299 (Online); ISSN: 2708-0099 (Print) DOI: 10.32996/ijllt Journal Homepage: www.al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/ijllt A Morpho-phonemic Analysis on Sasak Affixation Wahyu Kamil Syarifaturrahman1, Sutarman*2 & Zainudin Abdussamad3 123Fakultas Sosial dan Humaniora,Universitas Bumigora, Indonesia Corresponding Author: Sutarman, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: November 17, 2020 The current study analyses the morpho-phonemic in Sasak affixation especially in Accepted: January 02, 2021 Ngeno-Ngene dialect. This study is a qualitative research in nature. The data were Volume: 4 collected via field linguistic method using three techniques of data collection: Issue: 1 observation, interview, and note-taking. The study used a qualitative research method DOI: 10.32996/ijllt.2021.4.1.13 to describe all morphophonemic process of affixation in Ngeno-Ngene dialect of Sasak language. The results of the study revealed that there are two affixes that KEYWORDS undergo morphophonemic process, namely, prefix be-, pe-, ng-, t-, me- and simulfix ke-an. Prefix be- can cause epenthesis (additional r ), prefix pe- causes epenthesis Morpho-phonemic, Sasak, (additional n and mi) and assimilation ( k n), prefix ng- causes assimilation (k ŋ), Affixation, Ngeno-Ngene dialect prefix t- causes epenthesis (additional e) and prefix me- causes assimilation (p m). The simulfix ke-an in this dialect causes epenthesis in which there will be lexical addition ‘r,m,n’ when the simulfix ke-an is used. 1. Introduction 1 Affixation is an integral part of a language that has been discussed widely in most of languages in the world including Sasak language. -

On Passives of Passives Julie Anne Legate, Faruk Akkuş, Milena Šereikaitė, Don Ringe

On passives of passives Julie Anne Legate, Faruk Akkuş, Milena Šereikaitė, Don Ringe Language, Volume 96, Number 4, December 2020, pp. 771-818 (Article) Published by Linguistic Society of America For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/775365 [ Access provided at 15 Dec 2020 15:14 GMT from University Of Pennsylvania Libraries ] ON PASSIVES OF PASSIVES Julie Anne Legate Faruk Akku s¸ University of Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania Milena Šereikait e˙ Don Ringe University of Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania Perlmutter and Postal (1977 and subsequent) argued that passives cannot passivize. Three prima facie counterexamples have come to light, found in Turkish, Lithuanian, and Sanskrit. We reex - amine these three cases and demonstrate that rather than counterexemplifying Perlmutter and Postal’s generalization, these confirm it. The Turkish construction is an impersonal of a passive, the Lithuanian is an evidential of a passive, and the Sanskrit is an unaccusative with an instru - mental case-marked theme. We provide a syntactic analysis of both the Turkish impersonal and the Lithuanian evidential. Finally, we develop an analysis of the passive that captures the general - ization that passives cannot passivize.* Keywords : passive, impersonal, voice, evidential, Turkish, Lithuanian, Sanskrit 1. Introduction . In the 1970s and 1980s, Perlmutter and Postal (Perlmutter & Postal 1977, 1984, Perlmutter 1982, Postal 1986) argued that passive verbs cannot un - dergo passivization. In the intervening decades, three languages have surfaced as prima facie counterexamples—Turkish (Turkic: Turkey), Lithuanian (Baltic: Lithuania), and Classical Sanskrit (Indo-Aryan) (see, inter alia, Ostler 1979, Timberlake 1982, Keenan & Timberlake 1985, Özkaragöz 1986, Baker et al. -

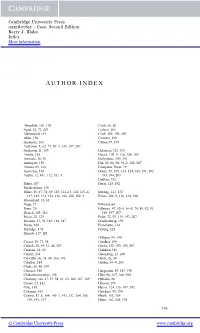

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. Blake Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Abondolo, 101, 105 Cook, 66, 80 Agud, 32, 72, 207 Corbett, 104 Aikhenvald, 191 Croft, 192, 193, 207 Allen, 150 Crowley, 100 Andersen, 163 Cutler, 99, 190 Anderson, J., 62, 71, 80–3, 135, 197, 207 Anderson, S., 109 Delancey, 123, 192 Anttila, 165 Dench, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Aristotle, 18, 30 Derbyshire, 100, 191 Armagost, 156 Dik, 62, 66, 68, 91–2, 188, 207 Artawa, 89, 124 Dionysius Thrax, 19 Austerlitz, 165 Dixon, 56, 105, 114, 124, 185, 191, 192, Austin, 12, 101, 112, 182–3 193, 194, 207 DuBois, 192 Baker, 187 Durie, 124, 192 Balakrishnan, 158 Blake, 15, 67, 78, 89, 107, 114–15, 124, 127–8, Ebeling, 121, 152 137, 143, 151, 154, 158, 186, 188, 192–3 Evans, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Bloomfield, 13, 63 Bopp, 37 Filliozat, 64 Bowe, 26 Fillmore, 47, 62–3, 66–8, 74, 80, 82, 91, Branch, 105, 116 188, 197, 207 Breen, 28, 125 Foley, 72, 92, 110, 192, 207 Bresnan, 47, 92, 185, 186, 187 Frachtenberg, 190 Bryan, 102 Franchetto, 124 Burridge, 174 Friberg, 123 Burrow, 117, 181 Gilligan, 99, 190 Caesar, 19, 73, 98 Giridhar, 100 Calboli, 18, 19, 31, 48, 207 Giv´on, 112, 192, 193, 207 Cardona, 64, 65 Goddard, 186 Carroll, 138 Greenberg, 15, 160 Carvalho, de, 31, 40, 186, 192 Groot, de, 30 Catullus, 184 Gruber, 67–9, 205 Chafe, 66, 80, 207 Chaucer, 148 Haegeman, 59, 187, 190 Chidambaranathan, 158 Hale, 96, 107, 168, 194 Chomsky, xiii, 47, 57, 58, 61, 62, 186, 187, 189 Halliday, 66 Cicero, 23, 112 Hansen, 193 Cole, 110 Harris, 124, 126, 147, 192 Coleman, 105 Hawkins, 99, 190 Comrie, 87–8, 104, 140–1, 142, 152, 154, 185, Heath, 155, 159 190, 191, 207 Heine, 162, 165, 193 219 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. -

Spatial Semantics, Case and Relator Nouns in Evenki

Spatial semantics, case and relator nouns in Evenki Lenore A. Grenoble University of Chicago Evenki, a Northwest Tungusic language, exhibits an extensive system of nominal cases, deictic terms, and relator nouns, used to signal complex spatial relations. The paper describes the use and distribution of the spatial cases which signal stative and dynamic relations, with special attention to their semantics within a framework using fundamental Gestalt concepts such as Figure and Ground, and how they are used in combination with deictics and nouns to signal specific spatial semantics. Possible paths of grammaticalization including case stacking, or Suffixaufnahme, are dis- cussed. Keywords: spatial cases, case morphology, relator noun, deixis, Suf- fixaufnahme, grammaticalization 1. Introduction Case morphology and relator nouns are extensively used in the marking of spa- tial relations in Evenki, a Tungusic language spoken in Siberia by an estimated 4802 people (All-Russian Census 2010). A close analysis of the use of spatial cases in Evenki provides strong evidence for the development of complex case morphemes from adpositions. Descriptions of Evenki generally claim the exist- ence of 11–15 cases, depending on the dialect. The standard language is based on the Poligus dialect of the Podkamennaya Tunguska subgroup, from the Southern dialect group, now moribund. Because it forms the basis of the stand- ard (or literary) language and as such has been relatively well-studied and is somewhat codified, it usually serves as the point of departure in linguistic de- scriptions of Evenki. However, the written language is to a large degree an artifi- cial construct which has never achieved usage in everyday conversation: it does not function as a norm which cuts across dialects.