Chapter 1: the Life and Times of John Owen 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter-Writing in the Early Swiss Reformation: Zwingli's Neglected Correspondence

Letter-Writing in the Early Swiss Reformation: Zwingli's Neglected Correspondence (Nigel Harris, Zürich, 7th May 2019) Is a letter a private document? Well, yes; or so I and probably all of us were brought up to believe. Certainly to this day, if a letter arrives at home addressed to my wife or to one of our children, I will on principle never open it – even if I know who it’s from and what it’s likely to contain. It just seems wrong. It seems, literally, none of my business. And so my instinct always tells me just not to do it. With some other kinds of communication, of course, the public/private divide is less clear cut. When I send an e-mail, for example, I can address a great many people at once. Some of them I probably will not know personally. And sometimes, of course, I might end up sending an e-mail by mistake to someone I am very keen actually shouldn’t read it. Mistaking the ‘reply’ button for the ‘reply to all’ button can, as we all know, get you into a lot of trouble. We’ve probably all been there. And with still more modern forms of ‘social’ media, such as Facebook and Twitter, this public/private divide can be still more problematic – so much so, indeed, that I at least shy away from them entirely. The idea of details about my private thoughts or my social and family life being shared, in principle, with absolutely anybody fills me with horror. What on earth has it got to do with anyone else? And, anyway, what gives me the right to imagine that other people are interested in what I’m doing or thinking? Isn’t that just arrogant? Well, I suppose that kind of attitude is a generational thing, and I’m showing my age in adopting it. -

Melanchthon Versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 44, Numbers 2-3 --- - - - JULY 1980 Can the Lutheran Confessions Have Any Meaning 450 Years Later?.................... Robert D. Preus 104 Augustana VII and the Eclipse of Ecumenism ....................................... Sieg bert W. Becker 108 Melancht hon versus Luther: The Contemporary Struggle ......................... Bengt Hagglund 123 In-. Response to Bengt Hagglund: The importance of Epistemology for Luther's and Melanchthon's Theology .............. Wilbert H. Rosin 134 Did Luther and Melanchthon Agree on the Real Presence?.. ....................................... David P. Scaer 14 1 Luther and Melanchthon in America ................................................ C. George Fry 148 Luther's Contribution to the Augsburg Confession .............................................. Eugene F. Klug 155 Fanaticism as a Theological Category in the Lutheran Confessions ............................... Paul L. Maier 173 Homiletical Studies 182 Melanchthon versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle Bengt Hagglund Luther and Melanchthon in Modern Research In many churches in Scandinavia or in Germany one will find two oil paintings of the same size and datingfrom the same time, representing Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, the two prime reformers of the Church. From the point of view of modern research it may seem strange that Melanchthon is placed on the same level as Luther, side by side with him, equal in importance and equally worth remembering as he. Their common achieve- ment was, above all, the renewal of the preaching of the Gospel, and therefore it is deserving t hat their portraits often are placed in the neighborhood of the pulpit. Such pairs of pictures were typical of the nineteenth-century view of Melanchthon and Luther as harmonious co-workers in the Reformation. These pic- tures were widely displayed not only in the churches, but also in many private homes in areas where the Reformation tradition was strong. -

Derbyshire Parish Registers. Marriages

^iiii iii! mwmm mmm: 'mm m^ iilili! U 942-51019 ^. Aalp V.8 1379096 GENEAUO^JY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00727 4282 DERBYSHIRE PARISH REGISTERS. riDarrtages. VIII. PHILLIMORES PARISH REGISTER SERIES. VOL. CLXIV (DERBYSHIRE, VOL. VIII.) One hundred and fifty printed. uf-ecj.^. Derbyshire Parish Registers. (IDarriaoes. Edited by W. P. W. PHILLIMORE, M.A., B.C.L., AND Ll. Ll. SIMPSON. VOL. VIII. yJ HonOon: Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co., Ltd., 124, Chancery Lane. — PREFACE This volume of Marriage Registers, the eighth of the Derbyshire series, contains the Registers of nine parishes, besides an odd Register for Ilkeston parish, omitted from the last volume. 1379096 It has not been thought needful to print the entries verbatim. They are reduced to a common form, and the following con- tractions, as before, have been freely used : w. = widower or widow. p. = of the parish of. co. = in the county of. dioc.= in the diocese of. lie. = marriage licence. It should be remembered that previous to 1752 the year was calculated as beginning on the 25th March, instead of the I St of January, so that a Marriage taking place on say 20th February, 1625, would be on that date in 1626 according to our reckoning ; but as the civil and ecclesiastical year were both used, this is sometimes expressed by 20th February, i62f. In all cases where the marriage is stated to have taken place by Licence, that fact is recorded, as the searcher thereby knows that further information as to age, parentage, and voca- tion of the parties is probably recoverable from the Allegations in the Archdeaconry or other ofifice from which the Licence was issued. -

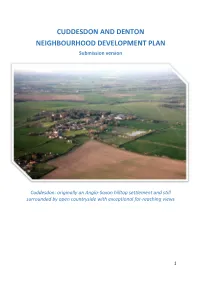

CUDDESDON and DENTON NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Submission Version

CUDDESDON AND DENTON NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Submission version Cuddesdon: originally an Anglo-Saxon hilltop settlement and still surrounded by open countryside with exceptional far-reaching views 1 SUMMARY 1. This document briefly describes the Neighbourhood Planning process for those who are unfamiliar with it and the village for those who have not visited it. This is followed by an assessment of the village character and then our vision and aims for the plan. It ends with a set of planning policies designed to deliver the vision and aims. 2. Cuddesdon and Denton is a small parish about 6 miles south east of Oxford with nearly 500 people in three distinct settlements – Cuddesdon, Chippinghurst and Denton. 3. Cuddesdon itself is home to Ripon College Cuddesdon, one of the largest theological colleges in the country and well known worldwide. Generations of theological students have appreciated the peace and tranquillity, as well as the stunning views of the surrounding countryside, a defining feature of the village. 4. The church and agriculture have shaped the parish for nearly 1500 years. More recently the Green Belt has maintained the character and protected the wonderful views across to the Chilterns, North Wessex Downs and Garsington. This protection is much valued by residents. 5. Cuddesdon is designated as a ‘Smaller’ unsustainable settlement with minimal services and within the Green Belt and is not expected to grow significantly. Denton and Chippinghurst are not classified meaning that growth is even less likely. 6. The parish has a mixed architectural style with some 28 Listed Buildings and Monuments. The theological college and Parish Church dominate the skyline from all sides. -

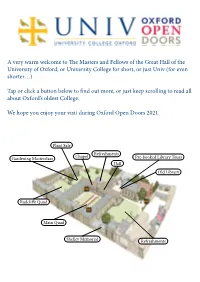

A Very Warm Welcome to the Masters and Fellows of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, Or University College for Short, Or Just Univ (For Even Shorter…)

A very warm welcome to The Masters and Fellows of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, or University College for short, or just Univ (for even shorter…) Tap or click a button below to find out more, or just keep scrolling to read all about Oxford’s oldest College. We hope you enjoy your visit during Oxford Open Doors 2021. Plant Sale Refreshments Gardening Masterclass Chapel Pre-booked Library Tours Hall Old Library Radcliffe Quad Main Quad Shelley Memorial Refreshments main quad Once Univ began to accept undergraduates in larger numbers, our medieval Quad was no longer large enough to accommodate everyone comfortably. In 1631, an Old Member called Sir Simon Bennet died, leaving the College a large sum of money, and it was possible to start afresh with a new Quad designed by Richard Maude. Its foundation stone laid on 17 April 1634. The West range was built first because we did not need to demolish any of the existing structures, and was finished in 1635, with work then starting on the North range, facing the High Street, with its tower. This was finished in 1637. In 1639 work began on the South range, with the Hall and the Chapel, but, just as the outer walls were finished in 1642, the English Civil War broke out and all building work stopped. In the 1660s work restarted in earnest. The Chapel was finished in 1666, and then the Kitchen wing to the South of the Quad was started in 1669. Finally in 1675 work started on the last range, on the East. -

Life of Philip Melanchthon

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08235070 7 Life of MELANciTHON m M \ \ . A V. Phu^ji' Mklanchthon. LIFE PHILIP MELAXCHTHOX. Rev. JOSEPH STUMP. A.M., WITH AN IXTKCDCCTIOS BY Rev. G. F. SPIEKER. D.D., /V<jri-iVi.»r .-.-" Cj:»r.-i ~':'sT:.'>y r* sAt LtttkiT^itJt TianiJgiir^ Smtimtry at /LLirSTRATED. Secoxp Epitiox. PILGER PUBLISHING HOUSE READING, PA. XEW YORK. I S g ;. TEE MEW YORK P'REFACE. The life of so distinguished a servant of God as Me- lanchthon deserves to be better known to the general reader than it actually is. In the great Reformation of the sixteenth century, his work stands second to that of Luther alone. Yet his life is comparatively unknown to many intelligent Christians. In view of the approaching four hundredth anni- versary of Melanchthon's birth, this humble tribute to his memory is respectfully offered to the public. It is the design of these pages, by the presentation of the known facts in Melanchthon's career and of suitable extracts from his writings, to give a truthful picture of his life, character and work. In the preparation of this book, the author has made use of a number of r^ biographies of ]\Ielanchthon by German authors, and of such other sources of information as were accessi- ble to him. His aim has been to prepare a brief but sufficiently comprehensive life of Melanchthon, in such a form as would interest the people. To what extent he has succeeded in his undertaking, others must judge. (V) That these pages may, in some measure at least, ac- complish their purpose, and make the Christian reader more familiar with the work and merit of the man of God whom they endeavor to portray, is the sincere wish of Thern Author.A CONTENTS, PAGE Introduction ix CHAPTER I. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough* substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wül be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nnsaber 9816176 ‘‘Ordo et lîbertas”: Church discipline and the makers of church order in sixteenth century North Germany Jaynes, JefiErey Philip, Ph.D. -

Philip Melanchthon's Influence on the English Theological

PHILIP MELANCHTHON’S INFLUENCE ON ENGLISH THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT DURING THE EARLY ENGLISH REFORMATION By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö A dissertation submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology August 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö To the memory of my beloved husband, Tauno Pyykkö ii Abstract Philip Melanchthon’s Influence on English Theological Thought during the Early English Reformation By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö This study addresses the theological contribution to the English Reformation of Martin Luther’s friend and associate, Philip Melanchthon. The research conveys Melanchthon’s mediating influence in disputes between Reformation churches, in particular between the German churches and King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1539. The political background to those events is presented in detail, so that Melanchthon’s place in this history can be better understood. This is not a study of Melanchthon’s overall theology. In this work, I have shown how the Saxons and the conservative and reform-minded English considered matters of conscience and adiaphora. I explore the German and English unification discussions throughout the negotiations delineated in this dissertation, and what they respectively believed about the Church’s authority over these matters during a tumultuous time in European history. The main focus of this work is adiaphora, or those human traditions and rites that are not necessary to salvation, as noted in Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana of 1530, which was translated into English during the Anglo-Lutheran negotiations in 1536. Melanchthon concluded that only rituals divided the Roman Church and the Protestants. -

Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2005 The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern Amy Nelson Burnett University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the History Commons Burnett, Amy Nelson, "The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern" (2005). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 99. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/99 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern In 1842, Carl Hundeshagen published Die Conflicte des Zwinglianismus, Lu- thertums und Calvinismus in der Bernischen Landeskirche von 1532-1558.' The book describes the doctrinal strife within Bern and the effects of that strife on the relationship of the Bernese church with those of Geneva and Zu- rich. The conflicts centered on two issues: the Lord's Supper, and the inde- pendence of the church from state control. As the title implies, Hundeshagen identified the three positions in the controversy as Zwinglian (as represented by Zurich and one of the factions in Bern), Calvinist (Geneva and Vaud), and Lutheran (the dominant faction in Bern during the later 1530s and 1540s). It is difficult to overestimate the impact of Hundeshagen's book. -

WHAT SORT of NACHFOLGER of ZWINGLI WAS BULLINGER? Joe

WTJ 82 (2020): 301–17 WHAT SORT OF NACHFOLGER OF ZWINGLI WAS BULLINGER? Joe Mock The secondary literature on Zurich theology often takes as its starting point the dependence of Heinrich Bullinger on the thought of Huldrych Zwingli. This is because Bullinger is regarded as Zwingli’s successor or Nachfolger, who closely followed and echoed Zwingli’s teaching. Further- more, “Zwinglianism” is often imprecisely equated with Zurich theology. This article examines those sections of Bullinger’s commentary on 1 Corinthians (1534) that discuss the Lord’s Supper. Bullinger does cite Zwingli’s Concerning the Protests of Eck (1530) and An Exposition of the Faith (1531) but none of the other works of Zwingli on the Lord’s Supper. Of particular note is Bullinger’s use of Ratramnus’s treatise on the Lord’s Supper (early 840s), which had influenced Berengar of Tours (c. 999– 1088). Although Zwingli did refer to the importance of 1 Cor 10:1–5 for understanding the Lord’s Supper it was Bullinger who, using Ratramnus’s treatise, made a more comprehensive study of this pericope to underscore feeding on Christ spiritually by the elect in the Lord’s Supper. Both Bullinger and Zwingli were trained in humanism, rhetoric, and the use of the biblical languages. Since both placed the utmost priority on correctly interpreting Scripture through judicial use of the tools they were trained and skilled in, it is not surprising that, unfettered by the tradition of the medieval church, they came, independently, to similar views of the Lord’s Supper. There were, of course, nuanced differences between their respective understandings of the Lord’s Supper. -

The Building of the Second Palace at Cuddesdon

The Building of the Second Palace at Cuddesdon By J. C. COLE N this paper I propose to discuss the surviving documents connected with I two legal disputes which arose in Oxford during the second half of the seventeenth century, from which we can learn some details of the building of the second palace at Cuddesdon and the craftsmen who were employed upon that work. The first of these disputes was brought before the Court of Arches in ,66g,' the second before the Vice-Chancellor's Court in ,681.' Before 1634 the Bishops of Oxford had no dwelling house especially appropriated to their use, but lived either in their parsonage houses or in hired lodgings in Oxford. In that year, as Anthony Wood tells us, William Laud, then Archbishop, persuaded the Bishop of Oxford, John Bancroft, to build a house for his own use and that of his successors' for ever '.3 The site chosen was the small village of Cuddesdon, of which Bishop Bancroft happened to hold the incumbency. The place was conveniently situated about five miles to the south-east of Oxford and not far from the old London Road. The building, which displaced an earlier parsonage house described as mean and ruinous,' was said to have cost about £2,600. King Charles gave his approval to the project and contributed fifty timber trees from the royal forest of Shot over as well as remitting a sum of £343 from the first fruits of the bishopric.' Several representations are to be found of the palace, which contemporaries called' a fair house of stone '.6 Laud paid it a visit of inspection in ,635' and stayed there again in ,636 on his way from London to Oxford to entertain the King.