DEMIFER Demographic and Migratory Flows Affecting European Regions and Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central and Southern Italy Campania, Molise, Abruzzo, Marche, Umbria and Lazio Garigliano

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR ENERGY DIRECTORATE D - Nuclear Safety and Fuel Cycle Radiation Protection Main Conclusions of the Commission’s Article 35 verification NATIONAL MONITORING NETWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL RADIOACTIVITY Central and Southern Italy Campania, Molise, Abruzzo, Marche, Umbria and Lazio DISCHARGE AND ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING Garigliano NPP Date: 12 to 17 September 2011 Verification team: Mr C. Gitzinger (team leader) Mr E. Henrich Mr. E. Hrnecek Mr. A. Ryan Reference: IT-11/06 INTRODUCTION Article 35 of the Euratom Treaty requires that each Member State shall establish facilities necessary to carry out continuous monitoring of the levels of radioactivity in air, water and soil and to ensure compliance with the basic safety standards (1). Article 35 also gives the European Commission (EC) the right of access to such facilities in order that it may verify their operation and efficiency. For the EC, the Directorate-General for Energy (DG ENER) and in particular its Radiation Protection Unit (at the time of the visit ENER.D.4, now ENER.D.3) is responsible for undertaking these verifications. The main purpose of verifications performed under Article 35 of the Euratom Treaty is to provide an independent assessment of the adequacy of monitoring facilities for: - Liquid and airborne discharges of radioactivity into the environment by a site (and control thereof). - Levels of environmental radioactivity at the site perimeter and in the marine, terrestrial and aquatic environment around the site, for all relevant pathways. - Levels of environmental radioactivity on the territory of the Member State. Taking into account previous bilateral protocols, a Commission Communication has been published in the Official Journal on 4 July 2006 with a view to define some practical arrangements for the conduct of Article 35 verification visits in Member States. -

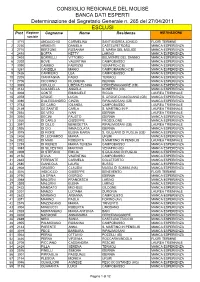

Elenco Idonei Ed Esclusi Progetto Formez

CONSIGLIO REGIONALE DEL MOLISE BANCA DATI ESPERTI Determinazione del Segretario Generale n. 265 del 27/04/2011 ESCLUSI Prot Ragione Cognome Nome Residenza MOTIVAZIONE sociale 1 3715 ANDACCHIO CARMELINA SANT'ANDREA JONICO FUORI TERMINE 2 2230 ARMENTI DANIELA CASTELPETROSO MANCA ESPERIENZA 3 2710 BERTONE ROSANNA S. MARIA DEL MOLISE MANCA ESPERIENZA 4 2493 BOFFA KETTY LARINO MANCA ESPERIENZA 5 2403 BORRELLI VITTORIO BELMONTE DEL SANNIO MANCA ESPERIENZA 6 2202 BOVE VALENTINA CAMPOBASSO MANCA ESPERIENZA 7 3090 CAMBIO FABRIZIO VENAFRO (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 8 3261 CANDELA MARIO CAMPOMARINO (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 9 2426 CARRIERO LEA CAMPOBASSO MANCA ESPERIENZA 10 2205 CIANFAGNA FABIO TERMOLI MANCA ESPERIENZA 11 2706 CICCHINO FILOMENA ISERNIA MANCA ESPERIENZA 12 3065 CIPULLO LIBERA ELSINA CERCEMAGGIORE (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 13 3144 COLABELLA ANGELA BONEFRO (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 14 3008 CONTE EMANUELE RICCIA LAUREA TRIENNALE 15 3078 CROCE LUCIA S. CROCE DI MAGLIANO (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 16 3086 D'ALESSANDRO CINZIA RIPALIMOSANI (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 17 2783 DE CARO IOLANDA CAMPOBASSO LAUREA TRIENNALE 18 2149 DE SANTIS CARLA S. MARTINO IN P. LAUREA TRIENNALE 19 2554 DE VITO IVAN ISERNIA LAUREA TRIENNALE 20 3050 DECINI FAUSTO ISERNIA MANCA ESPERIENZA 21 2920 DI CARLO GIUSEPPE FROSOLONE MANCA ESPERIENZA 22 3091 DI CILLO BENEDETTA RIPALIMOSANI (CB) LAUREA TRIENNALE 23 2926 DI CIO IMMACOLATA ISERNIA MANCA ESPERIENZA 24 3075 DI FIORE ELENA MARIA S. GIULIANO DI PUGLIA (CB) MANCA ESPERIENZA 25 2408 DI LEONARDO MARIA URURI MANCA ESPERIENZA 26 2932 DI MAIO -

The Long-Term Influence of Pre-Unification Borders in Italy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Blasio, Guido; D'Adda, Giovanna Conference Paper Historical Legacy and Policy Effectiveness: the Long- Term Influence of pre-Unification Borders in Italy 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: de Blasio, Guido; D'Adda, Giovanna (2014) : Historical Legacy and Policy Effectiveness: the Long-Term Influence of pre-Unification Borders in Italy, 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124400 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Elenco Siti Inquinati Presenti Nella

ELENCO SITI INQUINATI PRESENTI NELLA PROVINCIA DI CAMPOBASSO UBICAZIONE SITO INQUINATO DENOMINAZIONE TIPO DI INQUINANTE STATO ATTUAZIONE PROCEDIMENTO COMUNE LOCALITA' Impianti distribuzione carburanti Montenero di Bisaccia Area di servizio A14, Trigno Est ex P.V. Q8 n. 7601 Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Termoli Area di servizio A14, Rio Vivo Est P.V. Tamoil n.8109 Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Area di servizio A14, Rio Vivo Ovest P.V. Tamoil n.8110 Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Termoli Via Molise 8 P.V. Esso n. 6821 Idrocarburi Termoli S.S. 16 P.V. Q8 - Interpetrol s.r.l. Idrocarburi Predisposizione analisi di rischio Bojano Via Matese n.2 P.V. Agip n.7263 Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Campomarino S.S. 16 Km 522+0,16 P.V. Tamoil n. 7190 Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Castelmauro Corso Umberto I P.V. Esso n. 6815 Idrocarburi Indagini in corso per la caratterizzazione del sito Riccia (art. 249) Largo Garibaldi P.V. Esso n. 6839 Idrocarburi Caratterizzazione del sito Attività industriali in esercizio e dismesse Campobasso Stazione ferroviaria Via Novelli Trenitalia Idrocarburi Predisposizione caratterizzazione del sito Campobasso Via Crispi Ex officina gas Idrocarburi Bonifica in atto Termoli Nucleo Industriale C & T Inquinanti vari (es. cromo totale) Fasi propedeutiche alla individuazione origine dell'inquinamento e relativo responsabile. Termoli Nucleo Industriale Centrale Snow Storm Inquinanti vari (es. triellina) Fasi propedeutiche alla individuazione origine inquinamento e relativo responsabile. Termoli Nucleo Industriale Centrale Turbogas Sorgenia Inquinanti vari (es. solfati, manganese, ferro) Fasi propedeutiche alla individuazione origine superamento C.S.C. (eventuale inquinamento naturale di fondo) Termoli Nucleo Industriale Ex Flexys Inquinanti vari (es. -

Amhs Notiziario

AMHS NOTIZIARIO The Official Newsletter of the Abruzzo and Molise Heritage Society of the Washington, DC Area MAY 2014 Website: www.abruzzomoliseheritagesociety.org CARNEVALE AND THE BIG BANG THEORY Left - Dr. John C. Mather, Senior Project Scientist, James Webb Space Telescope, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, presents on The History of the Universe at the March 30, 2014 general Society meeting. Upper Right – The adorable children of Carnevale 2014 (from left,Cristina & Annalisa Russo, granddaughters of AMHS member Elisa DiClemente; Alessandra Barsi (Geppetto), Hailey Lenhart (a Disney princess), and Matteo Brewer (Arlecchino). Lower Right – Father Ezio Marchetto with Barbara Friedman and Peter Bell (AMHS Board Member), winners of the “Best Couple” prize (dressed as Ippolita Torelli and Baldassare Castiglione) at Carnevale 2014. (photo for March 30 meeting, courtesy of Sam Yothers; photos for Carnevale, courtesy of Jon Fleming Photography). NEXT SOCIETY EVENT: Sunday, June 1, 2014, 1:00 p.m. Silent Auction. See inside for details. 1 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT public. AMHS is proud to be a co-sponsor of this event with The Lido Civic Club of Washington, DC. (We are working to Dear Members and Friends/Cari Soci ed Amici, gain support of other Italian American organizations in the DC area). Additional details will follow at a later date – but please Well, I for one am very relieved mark your calendar! that the cold and snowy days might truly be behind us. In closing, I thank each of you for your continued support. Washington, DC is quite a lovely We are always open to hearing from our membership place in the springtime, with all regarding programs of interest, trips that we should consider of its splendor, tourists visiting organizing, etc. -

Molisans Between Transoceanic Vocations and the Lure of the Continent

/ 4 / 2011 / Migrations Molisans between transoceanic vocations and the lure of the Continent by Norberto Lombardi 1. The opening up of hyper-rural Molise After the armies had passed through Molise, on the morrow of the end of World War II, Molisans’ main preoccupation was not leaving their land and looking for better job and life prospects abroad. There were more immediate concerns, such as the return of prisoners, the high cost of living, rebuilding bombed towns, restoring roads and railways, restoring the water and electricity supply, and finding raw materials for artisanal activities. The recovery of the area was thus seen in a rather narrow perspective, as the healing of the wounds inflicted by the war to local society and the productive infrastructure, or, at most, as a reinforcement and development of traditional activities. The only sector where this perspective broadened was that of interregional transportation. The hope was to overcome the isolation of the region, although as a long-term project. When one peruses the local pages of the more or less politically engaged newspapers and journals that appeared with the return of democracy, and when one looks at institutional activities, especially those of the Consiglio provinciale di Campobasso, one is even surprised by the paucity and belatedness of references to the theme of emigration, deeply rooted as it is in the social conditions and culture of the Molisans.1 For example, one has to wait until 1949 for a report from Agnone, one of the historical epicenters of Molisan migration, to appear in the newspaper Il Messaggero.2 The report 1 For an overview of the phenomenon of migration in the history of the region, see Ricciarda Simoncelli, Il Molise. -

2I RETE GAS S.P.A

2i RETE GAS S.p.A. (incorporated in the Republic of Italy as a joint stock company) €3,500,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme Under this €3,500,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the “Programme”), 2i Rete Gas S.p.A. (the “Issuer” or “2iRG”) may from time to time issue notes (the “Notes”) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed €3,500,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Dealer Agreement described herein), subject to increase as described herein. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers specified under “Overview of the Programme” and any additional Dealer appointed under the Programme from time to time by the Issuer (each a “Dealer” and together the “Dealers”), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis. References in this Base Prospectus to the “relevant Dealer” shall, in the case of an issue of Notes being (or intended to be) subscribed by more than one Dealer, be to all Dealers agreeing to subscribe such Notes. An investment in Notes issued under the Programme involves certain risks. For a discussion of these risks see “Risk Factors”. This Base Prospectus has been approved by the Central Bank of Ireland (the “Central Bank”) as competent authority under Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended (including by Directive 2010/73/EU) (the “Prospectus Directive”). -

Prefettura - Ufficio Territoriale Del Governo Di Campobasso

Prefettura - Ufficio territoriale del Governo di Campobasso Oggetto: “Patto per la sicurezza” - Rete regionale di videosorveglianza. Più telecamere di sorveglianza nella Regione Molise. La Regione Molise ha pubblicato sul proprio sito internet il bando di gara per l’affidamento della progettazione esecutiva e l’esecuzione dei lavori relativi alla realizzazione del sistema regionale di videosorveglianza nei Comuni di Campobasso, Bojano, Campomarino, Guglionesi, Larino, Montenero di Bisaccia, Riccia, Termoli, Isernia, Agnone, Venafro. L’intervento si inquadra nel “Patto per la Sicurezza” stipulato il 13 febbraio 2015 tra le Prefetture di Campobasso e Isernia, la Regione Molise, tutti i Comuni molisani con popolazione superiore a cinquemila abitanti e, in attuazione degli indirizzi definiti dal Patto medesimo, è rivolto a rafforzare le misure per la sicurezza urbana nonché, più in generale, l’attività di prevenzione e vigilanza a tutela della sicurezza pubblica nell’intero territorio regionale. I Comuni suindicati saranno ognuno dotati di impianti per la videosorveglianza, tecnicamente omogenei e integrati in una rete regionale, che comprenderà complessivamente 419 punti di ripresa, rispondenti ad avanzati parametri tecnologici e ubicati in luoghi di particolare rilievo per il controllo del territorio, individuati anche con l’apporto delle Forze di Polizia. Ulteriori punti di ripresa, destinati a soddisfare preminenti necessità di controllo del territorio regionale, potranno essere attivati con gli ampliamenti finanziabili attraverso le economie eventualmente ottenute con l’aggiudicazione dell’appalto. Per ciascun Comune sarà allestita una sala operativa, con funzioni di governo del sistema comunale, nella quale sarà possibile visualizzare i flussi delle immagini provenienti dai punti di ripresa e accedere alle registrazioni. Le centrali operative delle Forze di Polizia potranno connettersi alle sale operative comunali per acquisire immagini e registrazioni d’interesse. -

The Extra Virgin Olive Oil Must Be Marketed in Bottles Or Containers of Five Litres Or Less

29.10.2002EN Official Journal of the European Communities C 262/9 4.8. Labelling: The extra virgin olive oil must be marketed in bottles or containers of five litres or less. The name ‘Alto Crotonese PDO’ must appear in clear and indelible characters on the label, together with the information specified in the rules governing labelling. The graphic symbol relating to the special distinctive logo to be used in conjunction with the PDO must also appear on the label. The graphic symbol consists of an ellipse enclosing, on a hill in the foreground, the bishop's palace of Acherentia, with the sky as a background. The colours used are brown 464 C for the bishop's palace, green Pantone 340 C for the hill on which it stands and blue Pantone 2985 C for the sky (see Annex). 4.9. National requirements: — EC No: G/IT/00200/2001.06.14. Date of receipt of the full application: 8 July 2002. Publication of an application for registration pursuant to Article 6(2) of Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin (2002/C 262/05) This publication confers the right to object to the application pursuant to Article 7 of the abovementioned Regulation. Any objection to this application must be submitted via the competent authority in the Member State concerned within a time limit of six months from the date of this publication. The arguments for publication are set out below, in particular under point 4.6, and are considered to justify the application within the meaning of Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92. -

Famiglia Casciato Book II Sabatino Mastroianni

Famiglia Casciato Book II The Descendants of Sabatino Mastroianni Compiled by John Vincent Casciato (With the help of many, many family members!) Introduction When I began researching my family tree back in1996, I decided to use Broderbund’s Family Tree Maker software to build my database. That decision was influenced by Broderbund’s offer to host family trees, and family information on their website for free. When genealogy.com acquired Family Tree Maker, they continued to host those pages but have now done away with that benefit and have removed those personal pages. (If you search the internet you may still find an outline of that data but all links are broken.) In retrospect, I should have built my database from scratch but it’s too late for that as it would take too much time to re-inter all the information from scratch and I fear that much data would be lost in an attempt to migrate from Family Tree Maker’s database into my own. Oh well, live and learn. Since I’m pretty much stuck using Family Tree Maker, I have attempted to recreate here, the data in a searchable PDF format. While organizing the data it became apparent that the database was too unwieldy to include everyone in one place as it currently contains names and information of over 1000 individuals. Were I able to print an all-in-one tree with just the names, it would be long enough to wrap around my house. My solution to that problem, while not exactly elegant, was to break the database into several “books.” The first is Famiglia Casciato, the database from which all others derive. -

Campobasso Local Action Plan Runup Thematic Network an URBACT II PROJECT II URBACT an 2 Contents

Campobasso Local Action Plan RUnUP Thematic Network AN URBACT II PROJECT II URBACT AN 2 Contents Foreword The Economic Assessment Campobasso in the RUnUP project How RUnUP relates to local strategies The role of Universities in Campobasso The URBACT Local Support Group Network event participation Campobasso Local Action Plan Conclusions 3 Foreword The RUnUP project represents a significant aspect of the Of course this means that the administration is in the complex effort of Campobasso community towards the front row to try to remove this difficult situation, putting re-qualification of Campobasso city as a regional capital. in motion resources, including private, for the recovery So a challenge, on one hand the need to confirm and affirm of the economy, to rebuild the trust of citizens urging its role as a regional capital city, the other must meet the the authorities and potential investors in a common external challenges in order to avoid marginalization and project, in order to make the city more liveable. To do provincialism where medium-sized cities may fall. this we need to intercept the needs and turn them into development policies, also with the support of funding at Surely this cannot be just the challenge of the national regional, European level. administration but should be a shared path shaking deep in the conscience of citizens and of all economic and The strategies adopted must deploy all the energy we scientific operators. need to bring out the individual and collective capacities to activate networking urban policies, keeping in mind This work is complex, it’s not enough producing strategic the employment, social cohesion and sustainable physical documents and proclamations but we have to immerse transformation of the area. -

Guardia Medica Is

SERVIZIO CONTINUITÀ ASSISTENZIALE (GUARDIA MEDICA) Provincia di ISERNIA ACQUAVIVA D’ISERNIA SEDE RIONERO SANNITICO V. ROMA 0865 848528 AGNONE V. MARCONI,22 0865 7221 BAGNOLI DEL TRIGNO SEDE CIVITANOVA DEL SANNIO V. PIAVESE 0865 830482 BELMONTE DEL SANNIO SEDE AGNONE V. MARCONI,22 0865 7221 CANTALUPO NEL SANNIO V. TAVERNA 0865 814357 CAPRACOTTA V. S. FALCONI, 3 0865 949121 CAROVILLI V. FONTE RITANA,1 0865 838266 CARPINONE SEDE SESSANO DEL MOLISE V. RIMEMBRANZA 0865 930320 CASTEL DEL GIUDICE SEDE CAPRACOTTA V. S. FALCONI, 3 0865 949121 CASTEL SAN VINCENZO SEDE ROCCHETTA AL VOLTURNO P. S.DOMENICO 0865 955385 CASTELPETROSO SEDE CANTALUPO NEL SANNIO V. TAVERNA 0865 814357 CASTELPIZZUTO SEDE MACCHIA D’ISERNIA PIAZZA MUNICIPIO 0865 55273 CASTELVERRINO SEDE AGNONE V. MARCONI,22 0865 7221 CERRO AL VOLTURNO SEDE ROCCHETTA AL VOLTURNO P. SAN DOMENICO 0865 955385 CHIAUCI SEDE SESSANO DEL MOLISE V. RIMEMBRANZA 0865 930320 CIVITANOVA DEL SANNIO V. PIAVESE 0865 830482 COLLI AL VOLTURNO V. G. MATTEOTTI 0865 957228 CONCA CASALE SEDE VENAFRO C/O OSPEDALE 0865 907743 FILIGNANO SEDE VENAFRO C/O OSPEDALE 0865 907743 FORNELLI SEDE COLLI AL VOLTURNO V. G. MATTEOTTI 0865 957228 FROSOLONE SEDE CIVITANOVA DEL SANNIO V. PIAVESE 0865 830482 ISERNIA V. S.IPPOLITO, 1 0865 442429 LONGANO SEDE MACCHIA D’ISERNIA PIAZZA MUNICIPIO 0865 55273 MACCHIA D’ISERNIA PIAZZA MUNICIPIO 0865 55273 MACCHIAGODENA SEDE CANTALUPO NEL SANNIO V. TAVERNA 0865 814357 MIRANDA SEDE ISERNIA V. S.IPPOLITO, 1 0865 442429 MONTAQUILA SEDE VENAFRO C/O OSPEDALE 0865 907743 MONTENERO VAL COCCHIARA SEDE RIONERO SANNITICO V. ROMA 0865 848528 MONTERODUNI SEDE MACCHIA D’ISERNIA PIAZZA MUNICIPIO 0865 55273 PESCHE SEDE ISERNIA V.