Artistry and Technique of Improvised Music: Reflections on the Compositions of Carlo Mombelli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Making Mistakes

The Art of Making Mistakes Misha Alperin Edited by Inna Novosad-Maehlum Music is a creation of the Universe Just like a human being, it reflects God. Real music can be recognized by its soul -- again, like a person. At first sight, music sounds like a language, with its own grammatical and stylistic shades. However, beneath the surface, music is neither style nor grammar. There is a mystery hidden in music -- a mystery that is not immediately obvious. Its mystery and unpredictability are what I am seeking. Misha Alperin Contents Preface (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Introduction Nothing but Improvising Levels of Art Sound Sensitivity Fairytales and Fantasy Music vs Mystery Influential Masters The Paradox: an Improvisation on the 100th Birthday of the genius Richter Keith Jarrett Some thoughts on Garbarek (with the backdrop of jazz) The Master on the Pedagogy of Jazz Improvisation as a Way to Oneself Main Principles of Misha's Teachings through the Eyes of His Students Words from the Teacher to his Students Questions & Answers Creativity: an Interview (with Inna Novosad-Maehlum) About Infant-Prodigies: an Interview (with Marina?) One can Become Music: an Interview (with Carina Prange) Biography (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Upbringing The musician’s search Alperin and Composing Artists vs. Critics Current Years Reflections on the Meaning of Life Our Search for Answers An Explanation About Formality Golden Scorpion Ego Discography Conclusion: The Creative Process (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Preface According to Misha Alperin, human life demands both contemplation and active involvement. In this book, the artist addresses the issues of human identity and belonging, as well as those of the relationship between music and musician. -

4 Classical Music's Coarse Caress

The End of Early Music This page intentionally left blank The End of Early Music A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century Bruce Haynes 1 2007 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2007 by Bruce Haynes Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haynes, Bruce, 1942– The end of early music: a period performer’s history of music for the 21st century / Bruce Haynes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-518987-2 1. Performance practice (Music)—History. 2. Music—Interpretation (Phrasing, dynamics, etc.)—Philosophy and aesthetics. I. Title. ML457.H38 2007 781.4′309—dc22 2006023594 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper This book is dedicated to Erato, muse of lyric and love poetry, Euterpe, muse of music, and Joni M., Honored and Honorary Doctor of broken-hearted harmony, whom I humbly invite to be its patronesses We’re captive on the carousel of time, We can’t return, we can only look behind from where we came. -

Page | 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. WAYNE SHORTER NEA Jazz Master (1998) Interviewee: Wayne Shorter (August 25, 1933-) Interviewer: Larry Appelbaum and audio engineer Ken Kimery Dates: September 24, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Description: Transcript. 26 pp. Shorter: ...his first three months’ royalty on “Sunny”... It was something... He didn’t have to play the bass. He said, “I’m not playing the bass...” He played in this club, at a restaurant... They’d shot a long scene in there, and did the...well, the thing that was...the Billy Strayhorn thing...you know, that Duke Ellington recorded... “Something in Paris.” [SINGS REFRAIN] Appelbaum: From An American In Paris? Shorter: [CONTINUES TO SING REFRAIN] That song that a lot of singers find hard to sing. Appelbaum: “Lush Life.” Shorter: “Lush Life.” There was some stuff in there. And Shawna(?—0:54) was playing the piano... She was between takes and everything. She was playing...she’s... Appelbaum: She can play. Shorter: Yeah. And tap dancing and all that. But she was like sand-dancing, and waiting for things and all that. I said, “Hey, why don’t you put her in...” Appelbaum: Did Ben Tucker co-write “I’m Comin’ Home, Baby”? Shorter: Ok. He wrote it. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Appelbaum: Oh, yeah? Shorter: Do you remember the mechanicals, “Notice Of Use” thing... There was something about that. -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Reflections on the Compositions of Carlo Mombelli

ARTISTRY AND TECHNIQUE OF IMPROVISED MUSIC: REFLECTIONS ON THE COMPOSITIONS OF CARLO MOMBELLI A Thesis to accompany the Portfolio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DMus (Composition) Carlo Mombelli University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg February 2007 Student no. 0316684N 1 THE ARTISTRY AND TECHNIQUE OF IMPROVISED MUSIC: REFLECTIONS ON THE COMPOSITION PORTFOLIO OF CARLO MOMBELLI Introduction The compositions presented in the accompanying DMus portfolio have evolved over many years and reflect changing stylistic traits from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. They do not represent a homogenous body of work even as ‘jazz compositions’, partly because in almost thirty years there are inevitable evolutions of style, and partly because there are several compositional approaches underlying them. Although it is possible to categorise the whole portfolio as ‘jazz’, it is only in the broadest sense, that of jazz as ‘an Afro- American musical idiom [to] which improvisation is crucially important’, as Martin Williams puts it (1983, 3,4). As Ingrid Monson also reminds us, however, jazz is both an idiom and a genre, and ‘itself subject to conflicting definitions’ (1996, 15), with a number of subcategories that have developed historically, such as blues, rhythm & blues, gospel, swing, bebop, cool. My works do not reflect all these historical developments (obviously), and they have been influenced by styles outside of jazz; but they do all have some relationship to the artistry and technique of improvisation because of the way I work as a composer, even if improvisation is not always used in every case as a performance technique in the finished product. -

English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 An examination of the place of the lute in 16th- and 17th-century English Society through a study of the English Lute Manuscripts of the so-called 'Golden Age', including a comprehensive catalogue of the sources. JULIA CRAIG-MCFEELY Oxford, 2000 A major part of this book was originally submitted to the University of Oxford in 1993 as a Doctoral thesis ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 All text reproduced under this title is © 2000 JULIA CRAIG-McFEELY The following chapters are available as downloadable pdf files. Click in the link boxes to access the files. README......................................................................................................................i EDITORIAL POLICY.......................................................................................................iii ABBREVIATIONS: ........................................................................................................iv General...................................................................................iv Library sigla.............................................................................v Manuscripts ............................................................................vi Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed sources............................ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS: ................................................................................................XII Palaeographical: letters..............................................................xii -

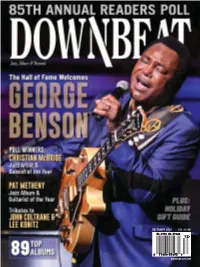

Monterey Jazz Festival

DECEMBER 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; -

Paul Motian Trio and Guest Bass Player Tobiography

www.winterandwinter.com P a u l M o t i a n 25 March 1931 – 22 November 2011 In many interviews, this New York drum- and recordings with Keith Jarrett, Charles mer of Turkish-Armenian extraction has Lloyd and Charlie Haden’s »Liberation been asked time after time for anecdotes Music Ensemble« follow, but over the about Bill Evans, Paul Bley and Keith Jar- years, almost unnoticed, Motian develops rett. His early days attract attention be- his first trio, with Bill Frisell on guitar and cause he was one of the few musicians who Joe Lovano on saxophone. In the mid- can look back on eighties, Motian experiences with begins to collab- Lennie Tristano, orate with Ste- Tony Scott and fan Winter ’s Coleman Haw- newly founded kins, who even music company appeared with JMT Production. Billie Holiday In contrast to and Thelonious the productions Monk in his up to this point, youth, and the first concept played with albums now ap- Arlo Guthrie at pear. The first is the legendary »Monk in Mo- Woodstock Fest- tian«, played by ival. The list of his trio, with great stars Mo- guest musicians tian has played Geri Allen on with goes on for Ꭿ Robert Lewis piano and pages; for some Dewey Redman years he has been reading through his on tenor saxophone. Next comes »Bill painstakingly documented annual calen- Evans«, recorded without pianist by the dars, to stir his memory and write his au- Paul Motian Trio and guest bass player tobiography. Marc Johnson. Winter & Winter, founded at It is not until 1972, at the age of 41, that the end of 1995, takes over and publishes Paul Motian records his debut album under all JMT’s productions, as well as continu- his own name (»Conception Vessel«, with ing work already begun. -

(561) 799-8547 Or (561) 799-8667 • LUXUR Y RENT AL RETI REMENT L IVIN G

wInter 201 8 no Homework • no tests • no stress JupIter spend an evening with political satirist and New York Times Best-selling author, p.J. o’rourke See page 31 edgar award-winning author and sports commentator John Feinstein returns to present “Backfield Boys: a Football mystery in Black and white” See page 47 winner of the 2009 pulitzer prize Important: in commentary, eugene robinson new parkIng presents “covering the presidency polIcIes in the modern media age” See page 51 See page 3 (561) 799-8547 or (561) 799-8667 • www.fau.edu/osherjupiter LUXUR Y RENT AL RETI REMENT L IVIN G A w orry-free w ay t o l ive a t t his g reat t ime i n y our l ife! No U pfront F ee ◆ E ndle ss O pportunitie s fo r S ocializ ing ◆ F in e D inin g ◆ P am per ing D ay S pa Tennis / P rivate G olf M embers hips ◆ C oncier ge S er vices ◆ Pe ts W el come ! Preferred r esiden ces going fa st! 800.49.Tow er Explore o ur fl oo r p lans a nd t ake a v irtual t our a t mo rselifetower .com/fau Marilyn & S tanley M . K atz S eniors C ampus 4850 Ryna Greenbaum Driv e, W est P alm Beach, Florida 334 17 We are pledged to the letter and spirit of U.S. policy f or the achievement of equal housing opportunity throughout the Na tion. We encoura ge and support an affi rma tive advertising and marketing prog ram in which there are no barriers to obtaining housing because of race, color , relig ion, sex, handica p, familial sta tus, or na tional orig in. -

The March 2009 Board Book

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF STATE INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER LEARNING Final Board Book March 18-19, 2009 AGENDA BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF STATE INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER LEARNING EDUCATION AND RESEARCH CENTER UNIVERSITIES CENTER 3825 RIDGEWOOD ROAD JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI March 18-19, 2009 Wednesday, March 18, 2009 COMMITTEE MEETING SCHEDULE A. Committee Meetings: ● 1:30 p.m. - Educational Policies and Programs ● 2:30 p.m. - Budget, Finance, and Audit ● 3:00 p.m. - Real Estate and Facilities ● 3:30 p.m. - Governance/Legal Times are approximate but all Committees will be adjourned by 5:00 p.m. Committees will begin following the conclusion of the previous committee meeting. Thursday, March 19, 2009 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ A. 8:30 a.m. – Call to Order B. Prayer – Ms. Robin Robinson C. Approval of Minutes ♦ February 18-19, 2009 Regular Board of Trustees Meeting D. Consent Agenda – Ms. Amy Whitten E. Efficiencies Report – Mr. Ed Blakeslee F. Educational Policies & Programs – Dr. Bettye Henderson Neely G. Budget, Finance, & Audit – Mr. Aubrey Patterson H. Real Estate & Facilities – Mr. Scott Ross I. Governance/Legal – Mr. Bob Owens J. Commissioner’s Search Update – Mr. Ed Blakeslee K. Chancellor’s Search Update – Ms. Amy Whitten L. Administration/Policy - Dr. Aubrey K. Lucas M. Commissioner’s Report - Dr. Aubrey K. Lucas N. Additional Agenda Items if Necessary O. Reconsideration P. Other Business/Announcements Q. Executive Session if Determined Necessary R. Adjournment BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF STATE INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER LEARNING MARCH 19, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES 1. February 19, 2009 Regular Board of Trustees Meeting....................................................................1 II. *CONSENT ITEMS A. -

Creative Musical Improvisation in the Development and Formation of Nexus Percussion Ensemble

! ! CREATIVE MUSICAL IMPROVISATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND FORMATION OF NEXUS PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE ! ! ! ! Olman Eduardo! Piedra ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements !for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL! ARTS May !2014 Committee: Roger B. Schupp, Advisor Gregory A. Rich, Graduate Faculty Representative Katherine L. Meizel John W. Sampen !ii ABSTRACT ! Roger B. Schupp, Advisor ! ! The percussion ensemble is a vital contemporary chamber group that has lead to a substantial body of commissions and premieres of works by many prominent composers of new music. On Saturday May 22nd, 1971, in a concert at Kilbourn Hall at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, NEXUS percussion ensemble, hailed by many as the world’s premiere percussion ensemble, improvised the entire program of their inaugural, 120 minute concert as a newly formed group, while using non-Western instruments with which the majority of the audience were unfamiliar.! NEXUS percussion ensemble has been influential in helping create new sounds and repertoire since their formation in 1971. While some scholarly study has focused on new commission for the medium, little attention has been given to the importance and influence of creative improvised music (not jazz) in the formation of NEXUS and its role in the continued success of the contemporary percussion ensemble.! This study examined the musical and cultural backgrounds of past and current members of NEXUS percussion ensemble, and the musical traditions they represent and recreate. The author conducted and transcribed telephone interviews with members of NEXUS percussion ensemble, examined scholarly research related to drumming traditions of the world and their use of improvisation, researched writings on creative improvisation and its methods, and synthesized !iii the findings of this research into a document that chronicles the presence of creative improvisation in the performance practices of NEXUS percussion ensemble.