Librarytrendsv35i3 Opt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

The SRRT Newsletter

Digital image from image Digital January 2021 Issue 213 Shutterstock . The SRRT Newsletter Librarians on Social Responsibilities Dear The SRRT Newsletter Readers, It’s difficult to even find the words to express what’s been going on in the world and in our country. COVID, a riot in Washington DC, unemployment, libraries closed. And then there’s the Georgia Senate race! How do libraries fit into all this? As I see it, we are a constant, as we provide reliable information, connections, resources, public spaces. With so many librar- Inside this issue ies closed or providing only curbside pickup right now, it’s more challenging for us, though. Where are our open public spaces? How do we serve our community members who From the Coordinator............................... 2 don’t have Internet access or a relevant device or even electricity? As conversations about how the SRRT Councilor Report ............................. 3 pandemic has exposed deep social inequities continue, I hope we can work with our communities to ALA Midwinter Virtual 2021 ..................... 2 address those inequities as best we can, even during a pandemic. These are difficult times for all of Voices From the Past ................................ 4 us and I’m proud to be in a profession that cares so much about their communities and comes up SRRT Minutes & Notes Page ..................... 4 with creative ways of continuing to serve everyone. FTF News .................................................. 5 Julie Winkelstein HHPTF News ............................................. 5 The SRRT Newsletter Co-Editor MLKTF News ............................................. 6 Features .................................................... 8 How I Exercise My Social During our current period of great strife and upheaval, it is also difficult to Responsibilities ................................... -

Alumni News Letter

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY '^T UKBANA^CHAMPAIGN Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from CARLI: Consortium of Academic and Researcii Libraries in Illinois http://www.archive.org/details/alumninewsletter91100univ p*^ NUMBER yi 197U ews Letteri^exxer j^--^^ Jbe Vniversity of JUinois LIBRARY SCHOOL ASSOCIATION UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY SCHOOL ASSOCIATION Annual Meeting Wednesday, July 10, 197^1 Cocktail Reception The Tower Suite of the Time & Life Building in Rockefeller Center Cash bar, no tickets are necessary Uk DMry flf the SEP 12 VJM University ot iiin<"S at ujUww CtMnKwmi UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY SCHOOL ASSOCIATION OFFICERS, 1973-7''^ Executive Board President: Mrs. Virginia Parker, Port Washington Public Library, Port Washington, New York IIO5O First Vice-President: Edwin S. Holmgren, 8 East ^i^Oth Street, New York, New York IOOI6 Second Vice-President: Mrs. Rosalie C. Amer, Cosumnes River College Library, 8U0I Center Parkway, Sacramento, California 95823 Secretary-Treasurer: John M. Littlewood, Documents Librarian, Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 618OI Director, 1971-7*^: Ellen Steininger, Librarian, Marsteller Incorporated, 1 East Wacher Drive, Chicago, Illinois 6060I Director, 1973-76: Madeline C. Yourman, I60 Columbia Heights, Brooklyn, New York 11201 Director, 1973-7'+: Mrs. Mata-Marie Johnson, 2l80 Windsor Way, Reno, Nevada 89503 Advisory Ccamnittee for Endowment Funds Robert F. Delzell, Director of Personnel, Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 618OI Robert W. Oram, Associate University librarian. Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 618OI Editor, News Letter Martha Landis, Reference Librarian, Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 6I8OI MINUTES OF THE 1973 ANNUAL MEETING On Wednesday evening, June 27, 1973, 58 alumni and guests met in the Americana West Room of the Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas. -

American Library Association Annual Report 2015

BECAUSE EMPLOYERS WANT CANDIDATES WHO KNOW THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A WEB SEARCH AND RESEARCH. BECAUSE PUNCTUATION WITHOUT IMAGINATION MAKES A SENTENCE, NOT A STORY. BECAUSE OF YOU, LIBRARIES TRANSFORM. ANNUAL REPORT 2015 141658 ALA 2016AnnualReport.indd 1 7/1/16 11:38 AM MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to “provide leadership for the development, promotion and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all.” This report highlights ALA’s 2015 fiscal year, which ended August 31, 2015. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring of 2016. 141658 ALA 2016AnnualReport.indd 2 7/1/16 11:39 AM DEAR FRIENDS, Because of you, the American Library Association (ALA) is helping America’s libraries transform communities and lives. The results are dramatic. Today, our nation’s public, academic and school libraries are reinventing themselves, opening their doors to new ideas, programs, and populations. In the process, they are transforming education, employment, entrepreneurship, empowerment and engagement. Public Libraries are champions in digital access and inclusion for all, while adding maker spaces, teen media labs and other new services to connect with new and changing audiences. Fact: Nearly 80 percent of libraries offer programs that aid patrons with job applications, interview skills, and résumé development. Academic Libraries are repurposing space, developing new student-centered technology programs and creating far-reaching ways to support sophisticated research using “big data.” Fact: Within the next five years, 79 percent of doctoral/research institutions are planning additions, renovations, refurbishments, or new buildings. -

2018 IMPACT REPORT This Report Highlights ALA’S 2018 Fiscal Year, Which Ended August 31, 2018

2018 IMPACT REPORT This report highlights ALA’s 2018 fiscal year, which ended August 31, 2018. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2019. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 57,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Friends, You made 2018 a wonderful year for libraries. Successes— including the increase in federal funding after the threatened elimination of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the launch of ALA’s Policy Corps, and the creation of the State Ecosystem Initiative—were all achieved because of you and your commitment to the profession of librarianship. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2018, including what is being done around ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development You will also find membership statistics, updates about our groundbreaking public awareness campaign Libraries Transform, financial highlights, and where ALA’s Disaster Relief Fund has helped libraries in need. You might have noticed that we have renamed our Annual Report. -

American Library Association 2009-2010 Annual Report | About ALA

American Library Association 2009-2010 Annual Report | About ALA http://www.ala.org/aboutala/annualreport10 You are at: ALA.org » About ALA » American Library Association 2009-2010 Annual Report Letter to the Membership About ALA 2009-2010 Year in Review Washington Office Programs and Partners Conferences and Workshops Publishing Leadership Financials Awards and Honors Other Highlights In Appreciation 1 of 2 03/25/2016 4:31 PM Letter to the Membership | About ALA http://www.ala.org/aboutala/governance/annualreport/annualreport/lettertothemembership/lette... You are at: ALA.org » About ALA » ALA Governance » Annual Report 2009-2010 redirect » Letter to the Membership Faced with a “perfect storm” of growing demand for library services and shrinking resources to meet that demand, libraries in 2009–2010 worked to provide critically needed materials and services such as technology training, online resources for employment, continuing education, and government resources. Across the country, library supporters lobbied decision-makers––often turning to social media to spread messages––in an effort to keep doors open and stave off cuts. In North Carolina, an online grassroots fundraising and awareness campaign through Facebook and Twitter helped convince trustees of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library to rescind a vote that would have closed 12 branches and laid off more than 140 library employees. The experience inspired CML Learning and Development Coordinator Lori Reed to create SaveLibraries.org, a clearinghouse of news and tools to fight library budget cuts and closings. In June, more than 2,000 turned out for Library Advocacy Day in Washington, D.C. Nearly five times larger than any National Library Legislative Day in the past, the event included a rally on Capitol Hill, meetings with elected officials, and a virtual component that drew another 1,000-plus participants to advocate for libraries by e-mailing members of Congress. -

0119-American-Libraries.Pdf

January/February 2019 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION p. 54 NEWSMAKER: Sonia Sotomayor p. 24 Mission Creep p. 40 The State of Net Neutrality p. 48 PLUS: Research Sprints, 2018 Year in Review, Referenda Roundup TRANSFORM THE FUTURE Leave a Legacy LA has left an indelible mark on society and our world. Since ALA LEGACY SOCIETY 1876, ALA has supported and nurtured library leaders, while HONOR ROLL OF DONORS A u u u advocating for literacy; access to information; intellectual freedom; Anonymous (3) John A. Lehner and diversity, equity, and inclusion. William G. Asp** Sarah Ann Long** The ALA Legacy Society includes members who are committed to Susan D. & Shirley Loo* Roger Ballard** leaving a legacy of their values and visions by including ALA in their Geri Hansen Mann** Robert E. Banks** Mike Marlin will, retirement plan, life insurance policy, or other estate plan. The Peggy Barber* Stephen L. Matthews 1876 Club is targeted to those under the age of 50 when they join Anne K. Beaubien** Carse McDaniel* who are planning to include ALA in their will, retirement plan, life John W. & Regina Minudri Alice M. Berry** insurance policy, or other estate plan. John N. Mitchell* Katharina Blackstead** Virginia B. Moore** Through the Legacy Society and 1876 Club, ALA members are Irene L. Briggs** David Mowery** helping to transform the future of libraries. The Development Francis J. Buckley, Jr. Jim & Fran Neal** Office staff is happy to work with you to design the right planned Michele V. Cloonan & Sidney E. Berger** Robert Newlen gift for you. Whether you are interested in an estate gift or naming Trevor A. -

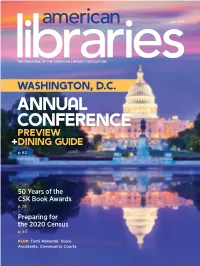

ENCE Annual CONFER

June 2019 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. Annual CONFERENCE PREVIEW +Dining Guide p. 62 50 Years of the CSK Book Awards p. 28 Preparing for the 2020 Census p. 44 PLUS: Tomi Adeyemi, Voice Assistants, Community Courts F A T H O M E V E N T S B R IN G S L IT E R A T U R E T O L IF E O N T H E B IG S C R E E N H A M L E T : N T L IV E 10 TH ANNIVERSARY JU LY 8 M A R G A R E T A T W O O D : L IV E IN C IN E M A S F R O M T H E H A N D M A ID 'S T A L E T O T H E T E S T A M E N T S SEPTEM BER 10 TCM BIG SCREEN CLASSICS PRESENTS T H E S H A W S H A N K R E D E M P T IO N 2 5 TH ANNIVERSARY S E P T E M B E R 2 2 , 2 4 & 2 5 TCM BIG SCREEN CLASSICS PRESENTS T H E G O D F A T H E R P A R T II N O V E M B E R 10 , 12 & 13 © 1994 CASTLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT. © 2018 WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. + B O N U S C O N T E N T N O T R A T E D June 2019 American Libraries | Volume 50 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 62 2019 Annual Conference Preview Washington, D.C. -

American Library Association 2014 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 i 132377 ALA 2015AnnualReport.indd 1 5/28/15 8:44 AM #THEFUTURE OFLIBRARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES, LIBRARIES ARE FOCUSED ON THE FUTURE. You can feel the momentum – the energy and excitement of change – when you walk into any library – public, school, academic or research. Libraries have doubled down on democracy, opening their doors wide to welcome and guide people as they search for a job, healthcare, a good read, or the resources to implement the next great idea. Academic libraries are reaching out to students with innovative ways to master the informa- tion skills required to thrive in the 21st century. Strong school library programs with certified school librarians ensure their students have the best chance to succeed. New collaborative spaces are joining books, computers and digital content to help libraries reinvent themselves, engage their community and build a new definition of the library as the center of every community across the country. ii | ALA TRENDiNG: LiBRARiES 132377 ALA 2015AnnualReport.indd 2 5/28/15 8:44 AM #THEFUTURE OFLIBRARIES This sea-change in libraries, created by the perfect storm of economic fall-out and digital acceleration, has been navigated by the American Library Association’s responsive action. ALA is harnessing emerging trends, promoting innovative techniques for librarians to shape their future and tapping into the best minds in the world to address emerging issues. WANT TO SEE THE FUTURE OF LIBRARIES? IT’S IN YOUR HANDS. 1 132377 ALA 2015AnnualReport.indd 1 5/28/15 8:44 AM THE COLLECTIVE IMPACT OF LIBRARIES Libraries. -

American Library Association Annual Report 2016

ACCESS PRIVACY DEMOCRACY DIVERSITY EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM PRESERVATION THE PUBLIC GOOD PROFESSIONALISM SERVICE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 2016 ANNUAL REPORT MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. This report highlights ALA’s 2016 fiscal year, which ended August 31, 2016. In order to provide an up- to-date picture of the association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2017. Dear Friends, Our nation’s libraries, librarians, and library workers serve all community members, offering services and educational resources that transform our patrons’ lives, open minds, and promote inclusion and diversity. In uncertain times, libraries provide the programs and services in areas such as education, employment, entrepreneurship, empowerment, and engagement that are vital to healthy communities. Your contributions allow the American Library Association (ALA) to support librarians and library workers in doing this transformative work. Libraries are at the center of important conversations taking place across our country. Whether it is access to information, protecting privacy, or digital broadband in rural areas, ALA and the library community have been there to advocate and defend on multiple fronts. ALA will be among the first to stand up if anything threatens to jeopardize our shared mission to serve every person. Because we recognize that libraries are for everyone, in January 2017 ALA Council approved another strategic direction, one that reinforces and sustains our work in equity, diversity, and inclusion. -

ALA 2012-2013 Annual Report

2012–2013 Annual Report Copyright © 2014 by the American Library Association. All rights reserved except those which may be granted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Copyright Revision Act of 1976. 2012–2013 Annual Report Contents Letter to the Membership | 2 About ALA | 4 Year In Review | 8 Washington Office |24 Programs and Partners | 29 2013 ALA Conferences | 40 Other Conferences | 51 Publishing | 56 Leadership | 66 Financials | 67 Awards and Honors | 73 Other Highlights | 94 In Appreciation | 102 Letter to the Membership continued to address its and ACRL Content Strategist Kathryn Deiss. The strategic goals in 2013 curriculum included leading in turbulent times, ALA by maintaining its strong interpersonal competence, power and influence, emphasis on the role of libraries in connecting the art of convening groups, and creating a culture and transforming communities. Among the year’s of inclusion, innovation, and transformation. highlights was a new initiative that provides librar- The program allowed participants to return to ies of all types with the tools and training they their institutions with greater self-awareness and need for innovative problem-solving and library- self-confidence, equipped with better skills for led community engagement. leading, coaching, collaborating, and engaging 2012–2013 ALA President Maureen Sullivan within their organizations and in their communi- continued the work of her predecessor, Molly ties, and to be better leaders, prepared to identify, Raphael, in the area of community engagement. develop, and implement solutions that will benefit Sullivan’s presidential year included several impor- all stakeholders. tant events that supported this agenda. Among Our current initiative, “Libraries Change them: Lives,” is framed around three areas of transforma- tive practice that enable community members to • An Advanced Leaders Training workshop that change their lives: literacy, community engage- empowered participants to use community ment, and innovation. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 Annual report i It starts with rethinking ALA. If we want to reinvent the role of libraries in our country, we have to re-engage ALA’s nearly 60,000 members. We have to harness the collective power of public, school, academic and special libraries and use it as a catalyst for how we connect, build and define communities. And how we lead them. Everything is on the table: education, social justice, leadership development, community advocacy, and yes, how we help people embrace the digital world. It’s a bold vision that requires courage and collaboration. Innovation and imagination. A way of thinking about information and technology yet to be discovered. ALA and America’s libraries have already begun to reimagine our future. Here’s what it looks like. REIMAGINING THE REIMAGINING FUTURE ALA ii 1 ALA’s special website, Transforming Libraries, is a robust collection of resources— Reimagining libraries research, tutorials, networking—to help libraries meet the immediate and ongoing demands in a digital environment that continues to expand at great speed. starts with rethinking ALA ALA continues to inspire and engage librarians to use their collective power. An ALA Midwinter Conference panel discussion, The Promise of Libraries Transforming America’s libraries have always been great centers of education and lifelong learning. During Communities, challenged librarians to step up to a new role as community leaders and help the past five years, America’s libraries have taught this country some valuable lessons bring their community together. about commitment, courage and community. ALA is rethinking the organization and reimagining its own future.