ED301227.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE P

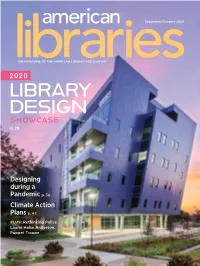

September/October 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE p. 28 Designing during a Pandemic p. 36 Climate Action Plans p. 42 PLUS: Rethinking Police, Laurie Halse Anderson, Puppet Troupe PLA 2020 VIRTUAL STREAM NOW ON-DEMAND Educational programs from the PLA 2020 Virtual Conference are now available on-demand*, including: Bringing Technology and Arts Programming to Senior Adults Creating a Diverse, Patron-Driven Collection Decreasing Barriers to Library Use Going Fearlessly Fine-Free Intentional Inclusion: Disrupting Middle Class Bias in Library Programming Leading from the Middle Part Playground, Part Laboratory: Building New Ideas at Your Library Programming for All Abilities Training Staff to Serve Patrons Experiencing Homelessness in the Suburbs We're All Tech Librarians Now Cost: for PLA members for Nonmembers for Groups *Programs are sold separately. www.ala.org/pla/education/onlinelearning/pla2020/ondemand September/October 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #9/10 | ISSN 0002-9769 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE The year’s most impressive new and renovated spaces | p. 28 BY Phil Morehart 22 FEATURES 22 2020 ALA Award Winners Honoring excellence and 42 leadership in the profession 36 Virus-Responsive Design In the age of COVID-19, architects merge future-facing innovations with present-day needs BY Lara Ewen 50 42 Ready for Action As cities undertake climate action plans, libraries emerge as partners BY Mark Lawton 46 Rethinking Police Presence Libraries consider divesting from law enforcement BY Cass Balzer 50 Encoding Space Shaping learning environments that unlock human potential BY Brian Mathews and Leigh Ann Soistmann ON THE COVER: Library Learning Center at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

The Newberry Annual Report 2016 – 17

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2016 – 17 Letter from the Chair and the President hat a big and exciting year the Newberry had in 2016-17! As Wan institution, we have been very much on the move, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees and Staff we are delighted to offer you this summary of the destinations we reached last year and our plans for moving forward in 2017-18. Financially, the Newberry enjoyed much success in the past year. Excellent performance by the institution’s investments, up 13.2 percent overall, put us well ahead of the performance of such bellwether endowments as those of Harvard and Yale. Our drawdown on investments for operating expenses was a modest 3.8 percent, well Chair of the Board of Trustees Victoria J. Herget and below the traditional target of 5.0 percent. In fact, of total operating Newberry President David Spadafora expenses only 22.9 percent had to be funded through spending from the endowment—a reduction by more than half of our level of reliance on endowment a decade ago. Partly this change has resulted from improvement in Annual Fund giving: in 2016-17 we achieved the greatest-ever single- year tally of new gifts for unrestricted operating expenses, $1.75 million, some 42 percent higher than just before the economic crisis 10 years ago. Funding for restricted purposes also grew last year, with generous gifts from foundations and individuals for specific programs and projects. Partly, too, our good financial results are owing to continued judicious control of expenses, exemplified by the fact that total staffing levels were 2.7 percent lower in 2016-17 than in 2006-07. -

Free Public Library Commission

10O£ Public Document No. 44 "B NINETEENTH REPORT FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS. 1909. BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 P o s t O f f ic e S q u a r e . 1909. Public Document No. 44 NINETEENTH REPORT OF THE FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS.'- 1909. BOSTON: WEIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 P o s t O f f ic e S q u a r e . \ 1909. K à T E L1BHA.KY Ur' lA S S A C H Q S ím DEC 311918 •TATI HOUSE »OSTO# A pproved by T h e S t a t e B o a r d o p P u b l ic a t io n . AA ^ Q 5 a. \ o<g> MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION. DELORAINE P. COREY, Malden, term expires 1913. Miss E. P. SOHIER, Secretary, Beverly, term expires 1912. C. B. TILLINGHAST, Chairman, Boston, term expires 1910. Mrs. MABEL SIMPKINS AGASSIZ, Yarmouth, term expires 1909. SAMUEL SWETT GREEN, Worcester,. term expires 1909. £l)c tíom m om ucaltl) of Jttassacljusctts. REPORT OF THE COMMISSION. To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives. In accordance with the provisions of chapter 347 of the Acts of the year 1890, under which the Free Public Library Commis sion was created, it herewith presents its nineteenth report, covering the fiscal year Dec. 1, 1907, to Nov. 30, 1908. T h e C o m m is s io n . Mr. Deloraine P. Corey has been reappointed by Governor Guild for the full term of five years from Oct. -

The SRRT Newsletter

Digital image from image Digital January 2021 Issue 213 Shutterstock . The SRRT Newsletter Librarians on Social Responsibilities Dear The SRRT Newsletter Readers, It’s difficult to even find the words to express what’s been going on in the world and in our country. COVID, a riot in Washington DC, unemployment, libraries closed. And then there’s the Georgia Senate race! How do libraries fit into all this? As I see it, we are a constant, as we provide reliable information, connections, resources, public spaces. With so many librar- Inside this issue ies closed or providing only curbside pickup right now, it’s more challenging for us, though. Where are our open public spaces? How do we serve our community members who From the Coordinator............................... 2 don’t have Internet access or a relevant device or even electricity? As conversations about how the SRRT Councilor Report ............................. 3 pandemic has exposed deep social inequities continue, I hope we can work with our communities to ALA Midwinter Virtual 2021 ..................... 2 address those inequities as best we can, even during a pandemic. These are difficult times for all of Voices From the Past ................................ 4 us and I’m proud to be in a profession that cares so much about their communities and comes up SRRT Minutes & Notes Page ..................... 4 with creative ways of continuing to serve everyone. FTF News .................................................. 5 Julie Winkelstein HHPTF News ............................................. 5 The SRRT Newsletter Co-Editor MLKTF News ............................................. 6 Features .................................................... 8 How I Exercise My Social During our current period of great strife and upheaval, it is also difficult to Responsibilities ................................... -

History of Urban Main Library Service

History of Urban Main Library Service JACOB S. EPSTEIN THEMOST IMPORTANT early date for urban public libraries would certainly be 1854, the year the Boston Public Library opened its doors. But as Jesse Shera has noted: “The opening, on March 20,1854, of the reading room of the Boston Public Library. ..was not a signal that a new agency had suddenly been born into American urban life. Behind the act were more than two centuries of experimentation, uncertainty, and change.”l Before the advent of public libraries there were numerous social li- braries, mercantile libraries and other efforts to have a community store of books which could be borrowed or consulted. A common prin- ciple evident in each of them was the belief that the printed word was important and should be made available to the ordinary citizen who could not own all the literature which was of value. Although it was a subscription library, rather than a public library as we think of it today, Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Phila- delphia, organized in 1731, was the first library in America to circulate books and the first to pay a librarian for his services. In his Autobiogra- phy, Franklin declared, “These libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans, made the common tradesmen and farm- ers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the stand so generally made throughout the colonies in defense of their privileges.”2 Here is that recurrent theme of self-improvement that runs throughout the Ameri- can public library movement. -

2019 ALA Impact Report

FIND THE LIBRARY AT YOUR PLACE 2019 IMPACT REPORT THIS REPORT HIGHLIGHTS ALA’S 2019 FISCAL YEAR, which ended August 31, 2019. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2020. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 58,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Colleagues and Friends, 2019 brought the seeds of change to the American Library Association as it looked for new headquarters, searched for an executive director, and deeply examined how it can better serve its members and the public. We are excited to give you a glimpse into this momentous year for ALA as we continue to work at being a leading voice for information access, equity and inclusion, and social justice within the profession and in the broader world. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2019, including updates on activities related to ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development We are excited to share stories about our national campaigns and conferences, the expansion of our digital footprint, and the success of our work to #FundLibraries. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

Free P Ublic Library Commission

PUBLIC DOCUMENT . N o . 44. FIFTEENTH REPORT OP THE F ree P ublic Library Commission op MASSACHUSETTS. 1905. BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 P ost Offic e Sq u a b e. 1905. UISSURY "U IM E S 8 U R Y M E R R ! MAC N / W ß U R Y RADFORD^ HÈ W BURYPOST Íc r o v e m x d ' METHUEN ROWLEY GEORGETOWN -CLARKSBURG MONROE /¡OXFORD IP S W IC H / PV/HCHEHÛON /D U N S T A B LE MORT H ANDOVER‘ RO/ALSTON ORACUT W a r w i c k EEYÛEN ¿ A N R E HU , TORS FIELD TYNGSBORO, / E F F E R EL L W/U/AAfSTOWN F tO W { A S H d f GLOUCESTER Ì. TEWKSBURY .ESSEX ^ srñaroStóaL- H B U R H H A M T O W N S E N DAS HEATH CÖERA/N NORTH FIELD LOWELL ~NORTH ADAMS ANDOVER- LMIDDLETON. R L OR IDA LUNENBURG CROTON W /OH/NCTON W E N HAM CHARLEMONT CREENEIELD e r v i n c MAGNOLIA ORANCE BEVERLY. AÈAN CHESTER piZss^jKBjm w iS T E O R D CHELMSFORD .s n e l E u r S e N . READING READING NEW ASHEORD *% & ***!£ $ SHIRLEY C AR ON ER ' ¿ANVERS A D A M S '"' HAWLEY ATHOL E IT C H BU R O s a v o r j P H / U I P S m ^ S/ÍLERICA- BUCNLAND MONTAGUE *.TEMPLETON $M £LBI/Pftr . 'BURLINGTON' T\\ CARLISLE HANCOCN LITTLETON. -WESTMINSTER , WAKE fTe l ò P eabôûÿ^ SALEM j y E N DE L L ''B Ò A BORO N E W S A L E M *¿Z HARVARD LANESBORO /OBURn m e Ch o s e m a r b l W e a d WINDSOR PLAIN FIELD Ú D ÍO R L ACTON LANCASTER LYNN. -

Librarytrendsv35i3 Opt.Pdf

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Library Trends VOLUME 35 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1987 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science Where necessary, permission is granted by the copyright owner for libraries and others registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) to photocopy any article herein for $3.00 per article. Pay- ments should be sent directly to the Copy- right Clearance Center, 27 Congress Street, Salem, Massachusetts 10970. Copy- ing done for other than personal or inter- nal reference use-such as copying for general distrihution. for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new rollective works, or for resale-without the exprrssed permission of The Board of Trustees of The lrniversity of Illinois is prohibited. Requests for special permis- sion or bulk orders should he addressed to The Graduate School of Library and Infor- miition Scirnte, 249 Armory Building, 505 E. Armory Sr.. Champaign. Illinois61820. Serial-fer code: 0024-2594/87 $3 + .OO. Copyright 0 1987 The Board of Trustees of The LJniversity of Illinois. Current Trends in Public Library Services for Children ANN CARLSON WEEKS Issue Ed itor CONTENTS Ann Carlson Weeks 349 INTRODUCTION Jill L. Locke 353 CHILDREN OF THE INFORMATION Margaret Mary Kimmel AGE: CHANGES AND CHALLENGES Alice Phoebe Naylor 369 REACHING ALL CHILDREN: A PUBLIC LIBRARY DILEMMA Dorothy J. Anderson 393 FROM IDEALISM TO REALISM: LIBRARY DIRECTORS AND CHIL- DREN’S SERVICES Barbara Elleman 413 LEARNING DIFFERENCES/LIBRARY DIRECTIONS: CURRENT TRENDS IN LITERATURE FOR CHILDREN Judith Rovenger 427 LIBRARY SERVICE TO CHILDREN WITH LEARNING DIFFERENCES Linda Ward-Callaghan 437 THE EFFECT OF EMERGING TECH- NOLOGIES ON CHILDREN’S LIBRARY SERVICE Barbara A. -

IDEALS @ Illinois

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Librarv/ Trends VOLUME 17 NUMBER 4 APRIL, 1969 The Changing Nature of the School Library MAE GRAHAM Issue Editor CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE MAE GRAHAM 343 Introduction B. LUCILE BOWIE , 345 Changing Perspective; in Educaiional Goals 'and Knowlkdge ' of the Learner ALBERT H. NAENY . 355 Changing Patterns in School Curriculum and Organization MARVIN R. A. JOHNSON 362 Facilities and Standbds * GAYLEN B. KELLEY * 374 Technological Advanles Affecting Schdol Inskuctional Materials Centers LWRA E. CRAWFORD . 383 The Changing Nature of Sihool Libra& Coll'ection's HELEN F. RICE 401 Changing Staff * Pattems aid Responsibilities' MARGARET HAYES GRAZIER . 410 Effects of Change on Education 'for Sdhool Librarians * JOHN MACKENZIE CORY 424 Changing Patterns of' Public Library aid Sdhool Librar; Rela tionships This Page Intentionally Left Blank Introduction MAE GRAHAM THEREWAS A TIME when it was fashionable to present to a young woman on her eighteenth birthday a china or copper plate on which was hand painted or etched the following couplet: Standing with reluctant feet Where the brook and river meet. It is the opinion of the editor of this issue of Library Trends that school libraries have now reached this enviable transition stage. There are healthy signs. A marriage has been arranged, represented by the 1969 Standards for School Media Programs prepared jointly by the American Association of School Librarians (ALA) and the Depart- ment of Audio-visual Instruction (NEA). Traditionally, marriages of convenience are arranged for purposes of consolidating and thereby increasing wealth, influence, and prestige and to produce a stronger dynasty. -

A View of the Internetâ•Žs Evolving Relationship to Information And

Pacific University CommonKnowledge Interface: The Journal of Education, Community Volume 10 (2010) and Values 11-1-2010 Information, Mediation, and Users: A View of the Internet’s Evolving Relationship to Information and Library Science Deborah Lines Anderson SUNY - University at Albany Recommended Citation Anderson, D.L. (2010). Information, Mediation, and Users: A View of the Internet’s Evolving Relationship to Information and Library Science. Interface: The Journal of Education, Community and Values 10(9). Available http://bcis.pacificu.edu/journal/article.php?id=738 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Interface: The Journal of Education, Community and Values at CommonKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 10 (2010) by an authorized administrator of CommonKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Information, Mediation, and Users: A View of the Internet’s Evolving Relationship to Information and Library Science Description In the realms of information, mediation, and users the Internet continues to have profound effects on information and library science. This article explores these effects through literature and research. It looks at whether information and library science have indeed come fully to terms with changes brought about by the Internet, or are still in the throws of contending with and adapting to this force that has taken over the field. Is the Internet an ve olving force or have we already fully seen its effects on the field? If the Internet