EU 049 804 INSTITUTION PUB DATE AVAILABLE FRCM Eres PRICE DESCRIPTORS IDENTIFIERS ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME LI 002 786 Penland, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE P

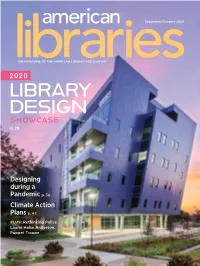

September/October 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE p. 28 Designing during a Pandemic p. 36 Climate Action Plans p. 42 PLUS: Rethinking Police, Laurie Halse Anderson, Puppet Troupe PLA 2020 VIRTUAL STREAM NOW ON-DEMAND Educational programs from the PLA 2020 Virtual Conference are now available on-demand*, including: Bringing Technology and Arts Programming to Senior Adults Creating a Diverse, Patron-Driven Collection Decreasing Barriers to Library Use Going Fearlessly Fine-Free Intentional Inclusion: Disrupting Middle Class Bias in Library Programming Leading from the Middle Part Playground, Part Laboratory: Building New Ideas at Your Library Programming for All Abilities Training Staff to Serve Patrons Experiencing Homelessness in the Suburbs We're All Tech Librarians Now Cost: for PLA members for Nonmembers for Groups *Programs are sold separately. www.ala.org/pla/education/onlinelearning/pla2020/ondemand September/October 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #9/10 | ISSN 0002-9769 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE The year’s most impressive new and renovated spaces | p. 28 BY Phil Morehart 22 FEATURES 22 2020 ALA Award Winners Honoring excellence and 42 leadership in the profession 36 Virus-Responsive Design In the age of COVID-19, architects merge future-facing innovations with present-day needs BY Lara Ewen 50 42 Ready for Action As cities undertake climate action plans, libraries emerge as partners BY Mark Lawton 46 Rethinking Police Presence Libraries consider divesting from law enforcement BY Cass Balzer 50 Encoding Space Shaping learning environments that unlock human potential BY Brian Mathews and Leigh Ann Soistmann ON THE COVER: Library Learning Center at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

The Newberry Annual Report 2016 – 17

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2016 – 17 Letter from the Chair and the President hat a big and exciting year the Newberry had in 2016-17! As Wan institution, we have been very much on the move, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees and Staff we are delighted to offer you this summary of the destinations we reached last year and our plans for moving forward in 2017-18. Financially, the Newberry enjoyed much success in the past year. Excellent performance by the institution’s investments, up 13.2 percent overall, put us well ahead of the performance of such bellwether endowments as those of Harvard and Yale. Our drawdown on investments for operating expenses was a modest 3.8 percent, well Chair of the Board of Trustees Victoria J. Herget and below the traditional target of 5.0 percent. In fact, of total operating Newberry President David Spadafora expenses only 22.9 percent had to be funded through spending from the endowment—a reduction by more than half of our level of reliance on endowment a decade ago. Partly this change has resulted from improvement in Annual Fund giving: in 2016-17 we achieved the greatest-ever single- year tally of new gifts for unrestricted operating expenses, $1.75 million, some 42 percent higher than just before the economic crisis 10 years ago. Funding for restricted purposes also grew last year, with generous gifts from foundations and individuals for specific programs and projects. Partly, too, our good financial results are owing to continued judicious control of expenses, exemplified by the fact that total staffing levels were 2.7 percent lower in 2016-17 than in 2006-07. -

MEDIA REPORT Changing Perceptions Through Television, the Rise of Social Media and Our Media Adventure in the Last Decade 2008 - 2018

KONDA MEDIA REPORT Changing Perceptions Through Television, The Rise of Social Media and Our Media Adventure in the Last Decade 2008 - 2018 November 2019 KONDA Lifestyle Survey 2018 2 / 76 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 2. CHANGING PERCEPTIONS THROUGH TELEVISION AND OUR DECENNIAL MEDIA ADVENTURE .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Relations with Technology / Internet Perception / Concern About Social Media ......... 7 2.2. Trust in Television News ................................................................................................ 11 2.3. Closed World Perception and Echo Chamber............................................................... 19 2.4. The State of Being a Television Society and Changing Perceptions ........................... 20 2.5. Our Changing World Perception Based on the Cultivation Theory .............................. 22 3. SOCIAL MEDIA USAGE IN THE LAST DECADE ............................................................. 27 4. CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................. 29 5. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 31 6. RESEARCH ID ............................................................................................................. -

The Email Is Down!

Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s Method to Analyze a 21 st Century Problem by Clyde H. Bentley Associate Professor Missouri School of Journalism University of Missouri and Brooke Fisher Master’s Student Missouri School of Journalism University of Missouri 181D Gannett Hall Columbia, MO 65211-1200 (573) 884-9699 [email protected] \ Presented to the Communications Technology and Policy Division AEJMC 2002 Annual Convention Miami Beach, Florida Aug. 7-10, 2000 1 of 19 2/19/2009 1:31 PM Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s method to analyze a 21 st century problem Abstract When the electronic mail system at a university crashed, researchers turned to a methodology developed more than 50 years earlier to examine its impact. Using a modified version of Bernard Berelson “missing the newspaper” survey questionnaire, student researchers collected qualitative comments from 85 faculty and staff members. Like the original, the study found extensive anxiety over the loss of the information source, plus a high degree of habituation and dependence on the new medium. 2 of 19 2/19/2009 1:31 PM Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s Method to Analyze a 21 st Century Problem It seldom puts lives at risk and almost always is accompanied by viable alternatives. -

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WOMEN's LEAGUE by Stephanie Herz the INSTITUTE of PUBLIC AFFAIRS B"Y Patrick J

c. c. SEPTEMBER OUR INTEREST IN THE CARIBBEAN By Wm. F. Montavon MSGR. HESSOUN CZECH LEADER By Rev. Wenceslas Michalicka THE WOMEN'S PARISH SODALITIES CONVENTION By Dorothy J. Willmann THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WOMEN'S LEAGUE By Stephanie Herz THE INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS B"y Patrick J. Ward OTHER FEATURES Dr. O'Hara Named Bishop of Great Falls, Montana-Church in America Mourns Archbishop Messmer-10th Anniversary of the N. C. W. C. News Service---"Religious Enlightenment" Main Topic of National Catholic Rural Life Conference-Plans Complete for National Eucharistic Congress at Omaha-No C. C. M. to Report Ex pansion of Program at Kansas City Convention-Reports of 1930 Meeting of Cath olic Central Verein of America and Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus N. C. C. W. to Sound Call for New Decade of Catholic Action-Reports of Meetings of Diocesan Units of N. C. C. W.-Program of "Catholic Hour" to November 2, 1930 -N. C. W. C. Activities in the Field of Immigration. All-Year Program for Catholic P. T. A. Groups Subscription Price VOL. XII, No.9 Domestic-$l.00 per year September, 1930 Foreign-=-$l.25 per year 2 N. C. W. C. REVIEW September, 1930 N. C. W. C. REVIEW OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WELFARE CONFERENCE N. C. w. C. ADMINISTRATIVE UThis organization (the N. C. N. C. W. C. DEPARTMENTS COMMITTEE W. C.) is not only useful, but AND BUREAUS MOST REV. EDWARD J. HANNA, D.D. Archbishcp of San Francisco necessary.. Wepraise all EXECUTIYE- Chairman who in any way cooperate in this The active executive of this De RT. -

56Th Annual Meeting O Fficers and Council 5 Corporate Supporters Committee Members 6 Gl O D Past Meetings of the STSA 7

SOU THERN THORACIC STSA SURGICAL ASSOCIatION 56 TH ANNUAL MEETING NOVE MBER 4 - 7, 2009 Marco Island Marriott Beach Resort Marco Island, Florida SPECI AL THANKS ta BLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL THANKS TO STSA 56TH ANNUAL MEETING O FFICERS AND COUNCIL 5 CORPORATE SUPPORTERS COmmITTEE MEMBERS 6 GL O D PAST MEETINGS OF THE STSA 7 Medtronic CLIFFORD VAN METER PRESIDENT’S AWARD 8 www.medtronic.com TIKI AWARD 9 St. Jude Medical OSLER ABBOTT AWARD 10-11 www.sjm.com KENT TRINKLE EDUCATION LECTURESHIP 11 SILVER HAWLEY H SEILER, M D RESIDENT AWARD 12 Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. MAVROUDIS-URSCHEL AWARD 12 www.ethiconendo.com STSA INSPIRATION AWARD 13 Maquet Cardiovascular www.maquet.com CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION OVERVIEW 14-15 DISCLOSURE POLICY 16-17 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 18-20 SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES 21-22 SURGICAL MOTION PICTURES 23 POSTGRADUATE PROGRAM 24-26 SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS 27-44 BASIC SCIENCE FORUM 30 GENERAL SESSION 33 CODING UPDATE AND ETHICS FORUM 40 HISTORY PRESENTATION 43 SCIENTIFIC PAPERS 45-203 EXHIBITORS 204-209 NECROLOGY REPORT 211 HONORARY MEMBERS 212 MEMBERSHIP ROSTER 213-312 GEOGRAPHIC LISTING OF MEMBERS 313-329 CONSTITUTION AND BYLAWS 330-341 RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE INDEX 342-350 INDEX OF AUTHORS 352-356 2 STSA 56th Annual Meeting STSA 56th Annual Meeting 3 F UTURE MEETING LOCATIONS 2009F OF ICERS AND COUNCIL N OVEMBER 3-6, 2010 P RESIDENT Disney Yacht & Beach Club Michael J Mack, MD Orlando, FL Dallas, TX NOVEMBER 9-12, 2011 PRESIDENT-ELECT JW Marriott San Antonio Hill Keith Naunheim, MD San Antonio, TX St. Louis, MO NOVEMBER 7-10, -

2019 ALA Impact Report

FIND THE LIBRARY AT YOUR PLACE 2019 IMPACT REPORT THIS REPORT HIGHLIGHTS ALA’S 2019 FISCAL YEAR, which ended August 31, 2019. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2020. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 58,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Colleagues and Friends, 2019 brought the seeds of change to the American Library Association as it looked for new headquarters, searched for an executive director, and deeply examined how it can better serve its members and the public. We are excited to give you a glimpse into this momentous year for ALA as we continue to work at being a leading voice for information access, equity and inclusion, and social justice within the profession and in the broader world. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2019, including updates on activities related to ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development We are excited to share stories about our national campaigns and conferences, the expansion of our digital footprint, and the success of our work to #FundLibraries. -

Fifteen Pages That Shook the Field: Personal Influence, Edward Shils, and the Remembered History of Media Research

Personal Influence’s fifteen-page account of the development of mass communication research has had more influence on the field’s historical self-understand- ing than anything published before or since. According to Elihu Katz and Paul Lazarsfeld’s well-written, two- stage narrative, a loose and undisciplined body of pre- war thought had concluded naively that media are powerful—a myth punctured by the rigorous studies of Lazarsfeld and others, which showed time and again that media impact is in fact limited. This “powerful-to- limited-effects” storyline remains textbook boilerplate Fifteen Pages and literature review dogma fifty years later. This article traces the emergence of the Personal Influence synop- That Shook the sis, with special attention to (1) Lazarsfeld’s audience- dependent framing of key media research findings and (2) the surprisingly prominent role of Edward Shils in Field: Personal supplying key elements of the narrative. Influence, Keywords: Paul Lazarsfeld; Edward Shils; Elihu Katz; media research; history of social Edward Shils, science; disciplinary memory and the The bullet model or hypodermic model posits Remembered powerful, direct effects of the mass media. Survey studies of social influence conducted in History of Mass the late 1940s presented a very different model from that of a hypodermic needle in which a Communication multistep flow of media effects was evident. That is, most people receive much of their Research information and are influenced by media secondhand, through the personal influence of opinion leaders (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955). —Joseph Straubhaar and Robert LaRose (2006, 403) By JEFFERSON POOLEY Jefferson Pooley is assistant professor of media and communication at Muhlenberg College. -

PAUL LAZARSFELD—THE FOUNDER of MODERN EMPIRICAL SOCIOLOGY: a RESEARCH BIOGRAPHY Hynek Jerábek

International Journal of Public Opinion Research Vol. No. –/ $. PAUL LAZARSFELD—THE FOUNDER OF MODERN EMPIRICAL SOCIOLOGY: A RESEARCH BIOGRAPHY Hynek Jerˇa´bek ABSTRACT Paul Lazarsfeld contributed to unemployment research, public opinion and market research, mass media and communications research, political sociology, the sociology of sociology, the history of empirical social research, and applied sociology. His methodological innovations—reason analysis, program analyzer, panel analysis, survey analysis, elaboration formula, latent structure analysis, mathematical sociology (especially the algebra of dichotomous systems), contextual analysis—are of special importance. This study responds to the critiques of Lazarsfeld’s ‘administrative research’ by Theodor W. Adorno, of ‘abstract empiricism’ by Charles W. Mills, and of the ‘Columbia Sociology Machine’ by Terry N. Clark. The paper discusses the merits of the team-oriented style of work presented in Lazarsfeld’s ‘workshop,’ his teaching by engaging in professional activities in social research and methodology, and his consecutive foundation of four research institutes, Vienna’s Wirtschaftspsychologische Forschungsstelle, the Newark Uni- versity Research Center, the Princeton Office of Radio Research, and the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University in New York. By his manyfold activities, Paul Lazarsfeld decisively promoted the institutionalization of empirical social research. All these merits make him the founder of modern empirical sociology. One hundred years have passed since the birth of the founder of modern empirical sociology, Paul Lazarsfeld. Without him, sociology today would not know terms and concepts such as panel study, opinion leader, latent structure analysis, program analyzer, elaboration formula, reason analysis, and many others. Lazarsfeld’s influence on empirical sociological research, market and public opinion research, and communication research has been much stronger than most of us realize. -

The Cultivation Theory

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X All you Need to Know About: The Cultivation Theory By Eman Mosharafa City University of New York, United States Introduction- In this paper, the researcher comprehensively examines the cultivation theory. Conceptualized by George Gerbner in the 1960s and 1970s, the theory has been questioned with every media technological development. In the last six decades, the mass communication field witnessed the propagation of cable, satellite, video games and most recently social media. So far, the theory seems to have survived by continuous adjustment and refinement. Since 2000, over 125 studies have endorsed the theory, which points out to its ability to adapt to a constantly changing media environment. This research discusses the theory since its inception, its growth and expansion, and the future prospects for it. In the first section of the paper, an overview is given on the premises/founding concepts of the theory. Next is a presentation of the added components to the theory and their development over the last sex decades including: The cultivation analysis, the conceptual dimensions, types and measurement of cultivation, and the occurrence of cultivation across the borders. GJHSS-A Classification : FOR Code: 130205p AllyouNeedtoKnowAboutTheCultivationTheory Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Eman Mosharafa. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

The Ethnic Factor in the Future of Inequality. INSTITUTION Center for Migration Studies, Inc

DOCUMENTRESUME ED 141 234 so 01Q 109 AUTHOR Tomasi,, Lydio F. TITLE The Ethnic Factor in the Future of Inequality. INSTITUTION Center for Migration Studies, Inc. , Staten Island, N.Y. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 39p. AVAILABLEFROM center for Migration studies, 209 ·Flagg Pl ace, Staten Island, Ne v York, New York 10 30 4 ($1.00 papertound) EDRS PRICE IIP-$0. 83 Plus Postage. BC .Not Available fromfro ■ EDRS. DESCRIPTORS cultural Background ; cultural Factors, €Cultural Pluralism; Pluralis ■ ; *Ethnic Groups; Ethnic studies; Futures (of society); Gr oup Membership ; Humaneu ■ an Dignity; Immigrants; I ■■ igrants ; • s ocial Change ; Social Developaent; Social Problems;Proble ■ s· Social Responsibility; •social Stratification; Social structure; Social Systems;sys t e ■ s ; Social Values; *Sociology; Theories ; . •United States History · ABSTRACT · The paper analyzes how the attemptatte ■ pt to assimilateassi ■ ilate ethnic groups into Americansociety has contributed to social, economic, ,cono ■ ic , and political inequality. The hy pothesis is that the official model■ odEl of classical sociology bas blinded us to a ·vast range . of social phenomenaphEno ■ ena which must■ o st be understood if we are to cope with the problems the----proble ■ s of contemporary■ porary lAmerica. ■ erica . While not often e xplicit, the American · 1 ■ er ican ideal that ethnic groofs should be incorporated into the melting ■ eltin9 pot bas created a society in which many■ any observable forms of inequality are perpetrated. This stratification analysis extends the concept of poverty beyond the narrow limitsli ■ its of incomeinco ■e to include political and personal relations. Amongl ■ ong issues addressed are _ i ■ ■ igrant immigrant,. social history, acceptance, po ver and elitist vs .