The Last Days of Pompeii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roman House As Memory Theater: the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Author(S): Bettina Bergmann Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Author(s): Bettina Bergmann Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Jun., 1994), pp. 225-256 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046021 Accessed: 18-01-2018 19:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin This content downloaded from 132.229.13.63 on Thu, 18 Jan 2018 19:09:34 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Bettina Bergmann Reconstructions by Victoria I Memory is a human faculty that readily responds to training reading and writing; he stated that we use places as wax and and can be structured, expanded, and enriched. Today few, images as letters.2 Although Cicero's analogy had been a if any, of us undertake a systematic memory training. In common topos since the fourth century B.c., Romans made a many premodern societies, however, memory was a skill systematic memory training the basis of an education. -

Heracles on Top of Troy in the Casa Di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii Katharina Lorenz

9 | Split-screen visions: Heracles on top of Troy in the Casa di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii katharina lorenz The houses of Pompeii are full of mythological images, several of which present scenes of Greek, few of Roman epic.1 Epic visions, visual experi- ences derived from paintings featuring epic story material, are, therefore, a staple feature in the domestic sphere of the Campanian town throughout the late first century BCE and the first century CE until the destruction of the town in 79 CE. The scenes of epic, and mythological scenes more broadly, profoundly undercut the notion that such visualisations are merely illustration of a textual manifestation; on the contrary: employing a diverse range of narrative strategies and accentuations, they elicit content exclusive to the visual domain, and rub up against the conventional, textual classifications of literary genres. The media- and genre-transgressing nature of Pompeian mythological pictures renders them an ideal corpus of material to explore what the relationships are between visual representations of epic and epic visions, what characterises the epithet ‘epic’ when transferred to the visual domain, and whether epic visions can only be generated by stories which the viewer associates with a text or texts of the epic genre. One Pompeian house in particular provides a promising framework to study this: the Casa di Octavius Quartio, which in one of its rooms combines two figure friezes in what is comparable to the modern cinematographic mode of the split screen. Modern study has been reluctant to discuss these pictures together,2 1 Vitruvius (7.5.2) differentiates between divine, mythological and Homeric decorations, emphasising the special standing of Iliad and Odyssey in comparison to the overall corpus of mythological depictions; cf. -

The Buried Cities of Campa Ia Their History

THE BURIED CITIES OF CAMPAIA THEIR HISTORY, THEIR DESTRUCTIO, AD THEIR REMAIS. By W. H. DAVEPORT ADAMS, " And in an hour of universal mirth, What time the trump proclaims the festival. Buries some capital city, there to sleep The sleep of ages — till a plough, a spade Disclose the secret, and the eye of day Glares coldly on the streets, the skeletons ; Each in his place, each in his gay attire. And eager to enjoy." ROGERS. 1870. SHAKSPEARE makes Malcolm say of the Thane of Cawdor, that " nothing in his life became him like the leaving it." Of Pompeii it may be said, that nothing in its history is equal in interest to its last scene. The fate of the gay Campanian city has been curious. Some cities have secured enduring fame by their commercial opulence, like Tyre ; by their art-wonders, like Athens ; by their world-wide power, like Rome ; or their gigantic ruins, like Thebes. Of others, scarcely less famous for their wealth and empire, the site is almost forgotten ; their very names have almost passed away from the memory of men. But this third-rate provincial town — the " Brighton" or " Scarborough" of the Roman patricians, though less splendid and far less populous than the English watering-places— owes its celebrity to its very destruction. Had it not been overwhelmed by the ashes- of Vesuvius, the student, the virtuoso, and the antiquary, would never have been drawn to it as to a VI PREFACE. shrine worthy of a pilgrim's homage. As a graceful writer has justly remarked, the terrible mountain, whilst it destroyed, has also saved Pompeii ; and in so doing, has saved tor us an ever- vivid illustration of anpient Roman life. -

Rethinking the Achilles at Skyros Myth: Two Representations from Pompeii

RETHINKING THE ACHILLES AT SKYROS MYTH: TWO REPRESENTATIONS FROM POMPEII Jackson Noah Miller A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Hérica Valladares Jennifer Gates-Foster Donald Haggis © 2020 Jackson Miller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jackson Noah Miller: Rethinking the Achilles at Skyros Myth: Two Representations from Pompeii (Under the direction of Hérica Valladares) Previous scholarship on the Pompeiian representations of the Achilles at Skyros myth has largely focused on how these works of art communicate moralizing messages about traditional gender roles. I argue, however, that artists seem especially interested in exploring and representing Achilles and Deidamia’s love story. Through a close analysis of images and texts, I demonstrate how amatory themes were central to Roman versions of this myth in both literature and art. By focusing on the decorative ensembles from the House of the Dioscuri and the House of Apollo I highlight the importance of these images’ architectural contexts in framing the viewer’s interpretation of this myth—a myth that touched on themes of love and loss. iii To my idol and mother, Dr. Nancy B. Jackson iv TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 II. Literary Evidence .......................................................................................... -

Passion, Transgression, and Mythical Women in Roman Painting

The Lineup: Passion, Transgression, and Mythical Women in Roman Painting BETTINA BERGMANN Mount Holyoke College [email protected] Pasiphae, Phaedra, Scylla, Canace, Myrrha – five mythological women who commited crimes of adultery, incest, treason, bestiality, and suicide – once adorned the walls of a small room in a second-century villa outside Rome. About one third lifesize and dressed in pastel colors, each figure stood alone against a white background, identified by the Latinized Greek name painted beside her head as well as by a posture of distress and a tell- ing attribute of self-destruction. Today the five women hang in separate, gilded frames in the small Sala degli Nozze Aldrobrandini of the Vatican Museums, where they are routinely overlooked by visitors gazing at the more famous Roman frescoes above them, the Aldobrandini Wedding and the Odyssey Landscapes1. 1 — This was held as a keynote lecture at the conference “Feminism & Classics VII: Visions in Seattle”, in May 2016. I am grateful to Jacqueline Fabre-Serris and Judith Hallett for their invitation to publish it and to Kathleen Coleman, Susanna McFadden, and Claudia Lega for their help. The frescoes have received little scholarly attention: Biondi (1843) 14-25; Nogara (1907) 55-59; Andreae (1963) 353-355; Micheli (2010). Since my lecture a succinct description of the frescoes has been published in Newby (2016) 189-194. EuGeStA - n°7 - 2017 200 BETTINA BERGMANN This distinctive group poses an immediate question: why would a second-century villa owner wish to embellish a domestic space with five (and perhaps more) anguished females? To modern eyes it seems puzz- ling that interior decoration would showcase dangerous women holding the ropes and daggers with which they will shed their own blood. -

Pompeiana : the Topography, Edifices and Ornaments of Pompeii

p I J *> •«(»» r %.. "^%" !^ : POMPEI ANA: TOPOGRAPHY, EDIFICES AND ORNAMENTS POMPEII, THE RESULT OF EXCAVATIONS SINCE 1819. BY SIR WILLIAM GELL, M. A. F. R. S. & F. S. A. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I. LONDON JENNINGS AND CHAPLIN. MDCCCXXXir. LONDON: PRINTED BY THOMAS DAVISON, WIIITEFRIAliS. II i LIST OF PLATES. Vol. I. Vol. II. Page Page PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR, opposite the Title-page I. ILLUSTRATED FRONTISPIECE GENERAL PLAN .... 1 III. SIDE OF A CUBICULUM, IN THE HOUSE OF FUSCUS 3 IV. SIDE OF A CHAMBER, IN THE HOUSE OF FUSCUS •-• V, WALL OF AN ATRIUM . 7 ^ •VI. DOOR OF A HOUSE . .5 -tvii. PICTURE IN A HOUSE BEHIND THE PANTHEON 9 -- VIII. STAIRS OF THE CRVPTO-PORTICUS OF EUMACHIA 14 ' IX. STATUE OF EUMACHIA '- X. PEDESTALS IN THE FORUM -"XI. ALTAR OF JUPITER XII. MARS AND VENUS .-XIII. GENERAL VIEW^ OF THE PANTHEON - XIV. WALL OF THE PANTHEON ..XV, PENELOPE AND ULYSSES •-XVI. jETHRA and THESEUS XVII. THALIA ^ XVIII. CELL OF THE TEMPLE OF AUGUSTUS XIX. PLAN OF THE TEMPLE OF FORTUNE --XX. TEMPLE OF FORTUNE 70 ^ XXI. RESTORATION OF THE TEMPLE OF FORTUNE 79 XXII. VIEW FROM THE ROOF OF THE THERM^iE 82 XXIII. PLAN OF THE THERMAE -XXIV. GENERAL VIEW OF THE THERMAE 89 -xxv. SECTION OF THE THERMS 108 XXVI. COURT OF THE THERM.'E • Referred to in Vol. I. page 5, as No. VII. t Referred to in Vol. I. page 9, as No. VI. LIST OF PLATES. Vol. I. Plate Page XXVII. FRIGIDARIUM XXVIII. NATATIO .... y*XXlX. TEPIDARIUM XXX. VAULT OF THE TEPIDARIUM XXXI. -

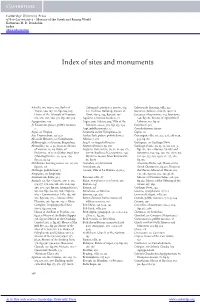

Index of Sites and Monuments

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-00230-1 - Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World Katherine M. D. Dunbabin Index More information Index of sites and monuments Acholla, 103, 104–5, 295; Baths of Colonnade, porticoes, 179–80, 304 Cabezón de Pisuerga, villa, 322 Trajan, 104, 107, 111, figs.104, 105; n.3; Triclinos Building, mosaic of Caesarea (Judaea), church, 196 n.19 House of the Triumph of Neptune, Hunt, 183–4, 234, figs.196, 197 Caesarea (Mauretania), 124; fountains, 105, 106, 280, 288, 310, figs.106, 309 Aquileia, Christian basilicas, 71 246, fig.261; Mosaic of Agricultural Agrigentum, 130 Argos, 299; Odeion, 304; Villa of the Labours, 117, fig.121 Ai Khanoum, palace, pebble mosaics, Falconer, 220–2, 305, figs.233, 234 Caminreal, 318 17 Arpi, pebble mosaics, 17 Camulodunum, 89–90 Aigai, see Vergina Arsameia on the Nymphaios, 30 Capsa, 117 Ain-Témouchent, 323 n.31 Arslan Tash, palace, pebble floor, 5 Carranque, villa, 155, 272, 276, 286 n.29, Alcalá de Henares, see Complutum Athens, 7, 271 323, fig.162 Aldborough, see Isurium Brigantum Augst, see Augusta Raurica Cartagena, see Carthago Nova Alexandria, 22–4, 32, 274 n.25; Mosaic Augusta Raurica, 79, 280 Carthage, Punic, 20, 33, 53, 101, 102–3, of warrior, 23, 24; Palace of Augusta Treverorum, 79, 81, 82, 94, 271, figs.101, 102; – Roman, Vandal and Ptolemies, 26 n.25; Shatby, Stag Hunt 317–18; Basilica of Constantine, 246; Byzantine, 103, 104, 107, 125, 127 n. 66, (Hunting Erotes), 20, 23–4, 254, Mysteries mosaic from Kornmarkt, 128, 130, 137, 138, 139 n.21, 257, 280, figs.22, 23, 24 82, fig.85 -

Visualizing the Aeneid in Decor

Visualizing the Aeneid in Roman Décor By Sarah Legendre A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Classics University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2019 by Sarah Legendre i Abstract This thesis investigates visual imagery inspired by the Aeneid in Roman décor, grouping the evidence diachronically. The ancient and modern theory of mimesis provides a framework to interpret how the imagery evokes the text; the imagery was not intended as an illustration. I discuss regional patterns and variations in relation to diachronic patterns. Artisans used Aeneid imagery which matched with Roman tastes for mythological imagery in art, such as scenes of couples and heroes. In Late Antiquity, patrons in the eastern empire preferred more general scenes, while patrons in the western empire chose to portray narrative episodes. Artisans and patrons used copybooks to transmit imagery during the imperial period, but in Late Antiquity imagery was inspired by theatrical performances, copybooks, or other popular imagery. Despite the Aeneid’s popularity as a text, the evidence herein confirms earlier suggestions that the visual and textual trajectories of the Aeneid were separate. ii Acknowledgements I owe my deepest gratitude to Dr. Lea Stirling, my supervisor and mentor, for the past two years of tireless mentorship, guidance, and patience she has extended to me. I am grateful that she provided me with the opportunity to study at the University of Manitoba and under her tutelage. I could not have asked for a better supervisor and mentor. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 26 February 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Thomas, Edmund (2011) Houses of the dead'? Columnar sarcophagi as 'micro-architecture'.', in Life, death and representation : some new work on Roman sarcophagi. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 387-435. Millennium-Studien = Millennium Studies. (29). Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110216783.387 Publisher's copyright statement: The nal publication is available at www.degruyter.com. Thomas, Edmund, 'Houses of the dead'? Columnar sarcophagi as 'micro-architecture'.; in: Elsner, Jas, Huskinson, Janet (eds.) of book, Life, death and representation: some new work on Roman sarcophagi., Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011, pp. 387-435. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk 1 2 3 4 12. 5 ‘Houses of the dead’? Columnar sarcophagi as 6 7 ‘micro-architecture’ 8 Edmund Thomas 9 10 11 At the end of the twentieth century architects across the world sought to bring 12 architecture closer to humanity. -

Achilles and the Roman Aristocrat: the Ambrosian Iliad As a Social Statement in the Late Antique Period Ceil Parks Bare

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Achilles and the Roman Aristocrat: The Ambrosian Iliad as a Social Statement in the Late Antique Period Ceil Parks Bare Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE ACHILLES AND THE ROMAN ARISTOCRAT: THE AMBROSIAN ILIAD AS A SOCIAL STATEMENT IN THE LATE ANTIQUE PERIOD By CEIL PARKS BARE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Ceil Parks Bare defended on March 2, 2009. __________________________ Paula Gerson Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________ Francis Cairns Outside Committee Member __________________________ Nancy T. de Grummond Committee Member __________________________ Rick Emmerson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________________________________________ Rick Emmerson, Chair, Department of Art History __________________________________________________________________________ Sally McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my husband. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people have supported and encouraged me during the past six years of this project. Florida State University’s Department of Art History and its faculty have provided consistent and invaluable training and guidance since my earliest days as an Undergraduate. In particular, I would like to thank Jack Frieberg and Patricia Rose for their faith in me through all these years. I would also like to thank the Department of Art History for research and writing grants including the Penelope Mason Graduate Fellowship for Research, the Penelope Mason Graduate Fellowship for Travel and various Graduate Assistantships. -

Roman Life and Manners Under the Early Empire

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Bettina Bergmann Reconstructionsby Victoriai

The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Bettina Bergmann Reconstructionsby VictoriaI Memory is a human faculty that readily responds to training reading and writing; he stated that we use places as wax and and can be structured, expanded, and enriched. Today few, images as letters.2 Although Cicero's analogy had been a if any, of us undertake a systematic memory training. In common topos since the fourth century B.c., Romans made a many premodern societies, however, memory was a skill systematic memory training the basis of an education. Memo- more valued than that of reading. This essay argues that ria, along with inventio (discovery), dispositio (organization), memory played a vital role in the creation and reception of elocutio (ornamentation through words or figures), and actio Roman pictorial ensembles in domestic situations. (performance in the manner of an actor, through speech and If you were to train yourself in the ancient art of memory, gestures), was one of the procedures of rhetoric, and thus a you would begin by forming mentally a clear series of places. fundamental part of almost every Roman's schooling. Pliny Three Latin rhetorical authors of the first centuries B.c. and the Elder, writing in the second half of the first century A.D., A.D., the anonymous author of the Ad Herennium, Cicero, and claimed that memory was the tool most necessary for life, but Quintilian, recommended that one choose a well-lit, spacious also the most fragile of human faculties. Trained in the house with a variety of rooms through which the mind can architectural memory system, a thinker about to speak would run freely.