Spatial Competition and Marketing Strategy of Fast Food Chains in Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/20/2016 GAIN Report Number: ID1640 Indonesia Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Food Service Hotel Restaurant Institutional Update Approved By: Ali Abdi Prepared By: Fahwani Y. Rangkuti and Thom Wright Report Highlights: The Indonesian hotel and restaurant industries grew 6.25 and 3.89 percent in 2015, respectively. Industry contacts attribute the increase to continued urbanization, tourism, and MICE (Meeting, Incentive, Conference, and Exhibitions) development. The Bank of Indonesia expects that economic growth will fall around 4.9 to 5.3 percent in 2016 and 5.2 to 5.6 percent in 2017. Post: Jakarta I. MARKET SUMMARY Market Overview Indonesia is the most populous country in the ASEAN region with an estimated 2017 population of 261 million people. It is home to approximately 13,500 islands and hundreds of local languages and ethnic groups, although the population is mostly concentrated on the main islands of Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Papua. It is bestowed with vast natural resources, including petroleum and natural gas, lumber, fisheries and iron ore. Indonesia is a major producer of rubber, palm oil, coffee and cocoa. In 2015, Indonesian GDP declined to 4.79 percent. The Bank of Indonesia expects economic growth will reach between 4.9 and 5.3 percent in 2016 and 5.2 to 5.6 percent in 2017. This contrasts with growth rates above 6 percent during 2007 to 2012 period. Inflation has ranged between 2.79 (August) and 4.45 (March) during the January-October 2016 period, while the rupiah has remained weak vis-à- vis the U.S. -

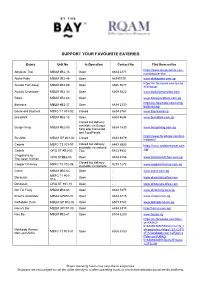

Support Your Favourite Eateries

SUPPORT YOUR FAVOURITE EATERIES Eatery Unit No In Operation Contact No. Find them online https://www.absolutethai.com. Absolute Thai MBLM #B2-16 Open 6634 2371 my/absolute-thai Aloha Poke MBLM #B2-46 Open 66340730 www.alohapoke.com.sg https://m.facebook.com/arcad Arcade Fish Soup MBLM #B2-69 Open 8566 9077 efishsoup/ Awfully Chocolate MBLM #B2-33 Open 6509 9422 www.awfullychocolate.com Boost MBLM #B2-64 Open www.boostjuicebars.com.sg https://m.facebook.com/living. Botanica MBLM #B2-37 Open 6634 2330 botanica.sg/ Boulevard Bayfront MBFC T1 #01-02 Closed 6634 8761 www.Boulevard.sg Breadtalk MBLM #B2-18 Open 6509 4644 www.breadtalk.com.sg Closed but delivery available via Burger Burger King MBLM #B2-03 6634 1530 www.burgerking.com.sg King app, Deliveroo and FoodPanda https://www.facebook.com/bus Bushido MBLM GP #01-02 Closed 6634 8879 hidoasia/ Closed but delivery Cedele MBFC T3 #01-07 6443 8553 https://www.cedelemarket.com available via website .sg/ Cedele ORQ ST #B2-02 TBC 6423 4882 Chopsticks by ORQ ST#B2-04 Open 6534 9168 www.theasiankitchen.com.sg The Asian Kitchen Closed but delivery Copper Chimney MBFC T3 #02-06 9238 1272 www.copperchimney.com.sg available via website Crave MBLM #B2-63 Open - www.crave.com.sg MBFC T1 #01- Dimbulah Open - www.dimbulahcoffee.com 01A Dimbulah ORQ ST #01-10 Open - www.dimbulahcoffee.com Din Tai Fung MBLM #B2-05 Open 6634 7877 www.dintaifung.com.sg Erwin's Gastrobar MBLM GP#01-01 Open 6634 8715 www.erwins.com.sg Forbidden Duck MBLM GP #02-02 Open 6509 8767 www.forbiddenduck.sg Harry's Bar MBLM GP#01-03 Open 6634 6318 http://harrys.com.sg/ Hey Bo MBLM #B2-41 Open 6974 6209 www.heybo.sg https://m.facebook.com/Men- ya-KAIKO- 616389838505564/menu/?p_r Hokkaido Ramen ef=pa&refsrc=https%3A%2F% MBFC T3 #01-01 Open 6509 8150 Men-ya KAIKO 2Fm.facebook.com%2Fpg%2 FMen-ya-KAIKO- 616389838505564%2Fmenu %2F&_rdr Shops operating hours may vary due to exigencies. -

How Much Do Japanese Really Care About Food Origin? a Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura Department of International Environm

How Much Do Japanese Really Care about Food Origin? A Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura Department of International Environmental and Agricultural Science Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology [email protected] Hikaru Hanawa Peterson Department of Applied Economics University of Minnesota [email protected] Selected Poster prepared for presentation at the 2016 Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, July 31 – Aug. 2. Copyright 2016 by Koichi Yamaura and Hikaru Hanawa Peterson. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided this copyright notice appears on all such copies. How Much Do Japanese Really Care about Food Origin? A Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura*1 and Hikaru Hanawa Peterson2 1Assistant Professor, Dept. of International Environmental & Agricultural Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture & Technology. [email protected] 2 Professor, Dept. of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota. [email protected] Problem Identification Objectives Results Gyudon, or beef bowl, is one of Japanese popular fast foods Examines the preferences of Japanese consumers toward food Latent Class model & WTP results Table 3. Latent Class model results for Beef Bowl consisting of a bowl of rice topped with beef and onion origins including beef, after the 3.11 Earthquake and the Meal Ingredients Class Probability Model Meal Ingredients focused focused focused focused simmered in a mildly sweet sauce flavored with soy sauce and Fukushima nuclear disaster and resumption of U.S. beef trade. PRICE -0.0198 *** -0.0119 ** FEMALE -1.2522 *** -- (0.0010) (0.0052) (0.2092) other seasoning. -

Burger Brawl It’S Hard to Tear Yourself Away from the Lure of a Good Burger, Even Though You Know You Should Enjoy Them in Moderation

MALEGRA M S • NUTRITIO N MALEGRA M S • NUTRITIO N f o o d f i g h t Burger Brawl IT’S HARD TO TEAR YOURSELF AWAY FROM THE LURE OF A GOOD BURGER, EVEN THOUGH YOU KNOW YOU SHOULD ENJOY THEM IN MODERATION. BUT if YOU’RE A DIEHARD FAN OF THE GREASY (ALBEIT YUMMIER) SIDE OF LifE, WE PUT SOME SIGNATURE BURGERS TO THE TEST TO fiND OUT WHICH ONE SLAPS A LITTLE LESS GUILT ON THAT EXPANDING WAISTLINE. Round one: fat Burger King’s Hard Rock Café MacDonald’s KFC Zinger Carls Junior’s Dan Ryan’s Swensen’s Mos Burger’s Whopper Junior Pig Sandwich Big Mac Fat 30.3 g Famous Star Burger Mushroom Yakiniku Rice Fat 22.3 g Fat 41 g Fat 30 g Burger Fat 28 g Chicken Burger Burger Fat 32 g Fat 55 g Fat 27 g Round two: Calories BK Whopper Junior KFC Zinger Dan Ryan’s Burger Mos Burger’s Yakiniku Rice Burger 420 calories 517 calories 690 calories 510 calories Round thRee: Protein And the Burger Baron is… BK whopper Junior BK Whopper Junior Mos Burger’s Yakiniku Rice Burger Protein 18 g Protein 16 g ASK THE Several studies have shown that Q: I READ THAT TAkiNG beneficial. Omega-6 fatty acids in DIETITIAN citrus fruit peels, white pith and EssENTIAL FATTY Acids wiLL safflower, soybean, corn, or can- Thomas Teh pulps contain phytonutrients and HELP wiTH my EczEMA prOBLEM. ola oils are called Linoleic Acid dietary fibre. Phytonutrients may HOW DO THEY HELP ME? (LA), which are converted to GLA reduce blood pressure and inflam- in the body. -

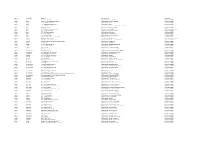

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

7-5-3 Day Japanese Tradition and Rite of Passage PAGE 5

Business cards, flyers, invitations and more! Contact printshop.stripes.com 042-552-2510 (extension77315) 227-7315 VOLUME 14 NO. 31 NOVEMBER 12 − NOVEMBER 25, 2020 SUBMIT STORIES TO: [email protected] STRIPESOKINAWA.COM FACEBOOK.COM/STRIPESPACIFIC FREE INSIDE INFO HAVE YOU EVER… A POEM BY WWII SAILOR PAGE 2 WHAT IS JAPAN’S THANKSGIVING? PAGE 3 Nakagusuku Castle Ruins MOS BURGER GOES VEGGIE PAGE 6 an architectural masterpiece Page 4 DEADLINES FOR SHIPPING HOLIDAY GIFTS NEAR PAGE 8 7-5-3 Day Japanese tradition and rite of passage PAGE 5 Special 8-page pullout inside! File photos 2 STRIPES OKINAWA A STARS AND STRIPES COMMUNITY PUBLICATION 75 YEARS IN THE PACIFIC NOVEMBER 12 − NOVEMBER 25, 2020 HAVE YOU EVER… A poem by a WWII sailor Editor’s Note: Cindy Pearson Gates sent this to Stars and Stripes. Here’s what she had to say: “Hello, my father, now passed, was a Max D. Lederer Jr. Publisher Boatswain’s Mate on an LST in the Battle of Biak. When he was Lt. Col. Richard E. McClintic 19, he wrote a poem after the battle that is poignant and raw and Commander honest. In his honor, I am putting it out there for you, in case you Chris Verigan would be interested in it.” Cindy, we are very interested. Thank Engagement Director you so much for sharing a part of your father with us. Marie Woods Publishing and Media Design Director Chris Carlson BY WILLIAM G. PEARSON Publishing and Media Design Manager Eric Lee Have you ever… Advertising and Circulation Manager Waited three months to catch up with your mail only to find it was Kentaro Shimura Production Manager sent back to your starting place? DUKW unloading at Biak. -

Chapter 1- Introduction

1 INTRODUCTION cDonald’s and Ray Kroc (1902–1984), the person most associated with it, were the subjects of the 2016 motion picture The Founder. However, MKroc was not the founder of McDonald’s. Nor was he the source of the early innovations that were the basis of that restaurant chain’sdistribute phenomenal suc- cess. Rather, it was the McDonald brothers—Richard and Maurice—who were the true founders of McDonald’s in 1937 and its realor innovators. Kroc was the ruthless force behind the franchising of McDonald’s restaurants and the eventual creation of what is now a globe-straddling chain of tens of thousands of restau- rants. But even Kroc could not have anticipated that McDonald’s would become the basis of one of the most influential developments in contemporary society. Its reverberations extend far beyond post,its point of origin both in the United States and in the fast-food business. It has influenced a wide range of businesses and many other types of organizations. Most generally, it is a global force affecting the way of life of a significant portion of the world.1 That impact continues and is likely to expand throughout the 21st century.2 * This chapter begins with a discussion of McDonaldization, the concept and process that copy,defines this book. After summarizing the basic principles that lie at the base of McDonaldization, its advantages and disadvantages (its “irrationali- ties”) are analyzed. We then turn to a discussion of McDonald’s itself and its rela- tionship to other “brick-and-mortar” consumption sites. -

Interview with the CEO

MOS FOOD SERVICES, INC. Interview with the CEO Switching to Fast Casual Fulfilling corporate social responsibility Q1: Same-store sales are recovering, showing a year-on-year increase in the second half of fiscal 2003, ended March 31, 2004. Please give us an overview of non-consolidated performance in fiscal 2003? According to the Japan Food Service Association, industry-wide same-store sales in 2003 declined 5.8% compared with the previous year, highlighting the tough conditions faced in the food service industry. Under these conditions, MOS concentrated efforts on product development to invigorate same-store sales. We developed the Nippon’s Burger Takumi, reflecting our passion and originality in creating delicious food, and continued to add new food creations to our menu. We also bolstered our time marketing strategy and aggressively worked to preserve the environment. As a result of repositioning and renovating stores, the total number of stores decreased, but the number of prime stores increased, substantially contributing to the recovery in same-store sales. Through these measures, sales of the MOS Burger chain rose 0.2%, the first increase in six fiscal years, although same-store sales declined 0.5% year on year. As a result, net sales increased 1.6% to ¥55,957 million, operating income climbed 23.2% to ¥2,178 million, and ordinary income grew 19.7% to ¥2,501 million. Net income declined 10.8% to ¥1,011 million, owing to the absence of an extraordinary gain of ¥1,016 million on the sales of subsidiary stock recorded in the previous fiscal year. -

S/N Tenant Name Unit Number S/N Tenant

MAPLETREE VOUCHER PARTICIPATING OUTLETS PARTICIPATING OUTLETS IN VIVOCITY UPDATED AS AT 1 APRIL 2020 S/N Tenant Name Unit Number S/N Tenant Name Unit Number S/N Tenant Name Unit Number 1 Aburi-En 01-159/160 117 Greendot 02-150 233 Rive Gauche Patisserie B2- K5 2 Action City 02-38 118 Guardian 02-79 234 Samsonite for Her 01-K5 3 Adidas B1-24/25 119 Guma Guma B2-K12 235 Samsung 02-28/29 4 Adidas Originals B1-06/07/11 120 H&M 01-19/20 236 Sans & Sans 02-191/192 5 Adonis 02-228/229 121 HaiDiLao HotPot 03-09 237 Secret Recipe 02-108/109 6 Aesop 01-06/07 122 HANS IM GLÜCK 01-57 238 SEIKO 01-03 7 AIBI Style 02-160/161 123 Henri Charpentier 02-K4/K5 239 Selffix DIY B2-20/21 8 AKEMIUCHI 02-202 124 Honeymoon Dessert 01-93 240 Sephora 01-178 9 Akimitsu 01-54/55/56 125 House of Samsonite 01-91 241 SF Juice B2-05A 10 ALDO 01-192 126 Hush Puppies 02-65/67 242 Shin Kushiya 02-120/121/122 11 Analogue+ 02-10 127 Hysses 01-K22 243 Shoppes by Meir & Co. 02-237 12 AOne Signature 02-128/130 128 Ichiban Boshi B2-07/08/09 244 Simply Toys and Toy Outpost 02-32/33 13 Apgujeong Hair Studio 02-216 129 Innisfree B1-02 245 Singtel 02-216C 14 Artea 01-100/101 130 iROO 01-179/182 246 Skechers 02-25 15 Artisan Boulangerie Co. -

For Fiscal Year Ended March 2014 (Japanese Accounting Standards)

Financial Results (Consolidated) for Fiscal Year Ended March 2014 May 14, 2014 (Japanese accounting standards) Name of listed firm: Zensho Holdings Co., Ltd. Exchange: TSE Code no.: 7550 URL http://www.zensho.co.jp/ Representative: (title) Chairman of the Board and CEO (name) Kentaro Ogawa (title) Executive Officer, Senior Address any inquiries to: General Manager of Group Finance (name) Takemi Kaneko (tel.) 03 (6833) 1600 and Accounting Division Date of annual general meeting of shareholders (planned): June 24, 2014 Starting date of dividend payment (planned): June 25, 2014 Date of submittal of securities report (planned): June 25, 2014 Supplemental explanatory materials on consolidated financial results prepared? Y / N Investors meeting held on settlement of accounts? Y / N (for institutional investors) (Figures rounded down to the nearest million yen) 1. Consolidated financial performance in the fiscal year ended March 2014 (April 1, 2013 – March 31, 2014) (1) Consolidated business performance (Percentages [%] indicate changes from the previous year) Sales Operating profit Ordinary profit Net profit Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of yen % FY 2014 468,377 12.2 8,134 (44.8) 7,957 (42.6) 1,103 (78.2) FY 2013 417,577 3.6 14,736 (29.8) 13,873 (28.1) 5,058 64.8 (Reference) Comprehensive income FY 2014: 2,129 million yen (down 70.4%) FY 2013: 7,204 million yen (up 38.7%) Net profit per share– Return on Return on Operating profit Net profit per share assuming dilution equity (ROE) assets (ROA) ratio yen yen -

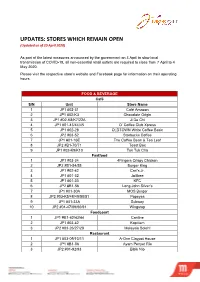

STORES WHICH REMAIN OPEN (Updated As of 20 April 2020)

UPDATES: STORES WHICH REMAIN OPEN (Updated as of 20 April 2020) As part of the latest measures announced by the government on 3 April to slow local transmission of COVID-19, all non-essential retail outlets are required to close from 7 April to 4 May 2020. Please visit the respective store's website and Facebook page for information on their operating hours. FOOD & BEVERAGE Café S/N Unit Store Name 1 JP1 #02-31 Café Amazon 2 JP1 #02-K3 Chocolate Origin 3 JP1 #02-K8/K7/22A Ji De Chi 4 JP1 #01-43/44/45 O’ Coffee Club Xpress 5 JP1 #02-28 OLDTOWN White Coffee Basic 6 JP2 #03-52 Starbucks Coffee 7 JP1 #01-16E The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf 8 JP2 #B1-70/71 Toast Box 9 JP1 #02-K9/K10 Tuk Tuk Cha Fastfood 1 JP1 #03-34 4Fingers Crispy Chicken 2 JP2 #B1-54/55 Burger King 3 JP1 #02-42 Carl’s Jr. 4 JP1 #01-32 Jollibee 5 JP1 #01-30 KFC 6 JP2 #B1-56 Long John Silver’s 7 JP1 #01-30A MOS Burger 8 JP2 #03-K5/48/49/50/51 Popeyes 9 JP1 #01-33A Subway 10 JP2 #01-47/89/90/91 Wingstop Foodcourt 1 JP1 #B1-42/43/44 Cantine 2 JP1 #03-42 Kopitiam 3 JP2 #03-26/27/28 Malaysia Boleh! Restaurant 1 JP1 #03-09/10/11 A-One Claypot House 2 JP1 #B1-06 Ayam Penyet Ria 3 JP2 #01-92/93 Bibik Nio 4 JP1 #02-24/K5 BRIO 5 JP2 #03-90 to 95 Central Hong Kong Café 6 JP2 #03-96 to 104 Crystal Jade La Mian Xiao Long Bao 7 JP2 #B1-57/58/59 Dian Xiao Er 8 JP2 #B1-68/69 Din Tai Fung 9 JP2 #01-76 to 78 EAT. -

What Works, What Doesn't

MASTER, REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL FRANCHISING REPORT: FRANCHISES, BUSINESS, Global CULTURE Franchise www.globalfranchisemagazine.com ASIA WHAT WORKS, WHAT DOESN’T. HOW TO JOIN THE FRANCHISES EARNING SUCCESS Ichiro Fujita advises on franchising in Japan Japan Report Receptive to Western ideas and culture, Japan has long been a target destination for Western franchisors. However, brands eager to set up shop in this lively market should look carefully before they leap; this country may appear thoroughly Westernized, but cultural differences run deep and these should be properly understood before that first step Eastwards is taken. Ichiro Fujita, who assisted us with this project, is President/CEO of I. Fujita International, Inc, and has long experience of assisting incoming brands to franchise Global in Japan – he is an ideal guide for anyone thinking of dipping a Franchise toe in the water. ASIA Ross ADVERTISEMENT SALES DIRECTOR Mark Forsyth +44 1323 471291 [email protected] GROUP ADVERTISEMENT MANAGER Richard Davies +44 1323 471291 [email protected] SENIOR ACCOUNTS MANAGER Neil Phillips +44 1323 471291 [email protected] SENIOR ACCOUNTS MANAGER Tom Hepton +44 1206 505487 [email protected] ACCOUNT MANAGER Craig Bartlett +44 1323 471291 [email protected] HEAD OF EDITORIAL (BUSINESS) Fae Gilfillan [email protected] EDITOR Ross Gilfillan [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Lloyd Oxley CREDIT CONTROL Sue Carr +44 1206 505903 PUBLISHER Matthew Tudor globalfranchisemagazine.com Global Franchise ASIA Japan hat services do you offer expanding brands? Our consulting company assists US franchisors to facilitateW market entry specifically into Japan. Over 30 years of operations, we have helped well over 100 companies to identify their Franchise master licensees in Japan.