Kansas Intercity Bus Study Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Station Conceptual Engineering Study

Portland Union Station Multimodal Conceptual Engineering Study Submitted to Portland Bureau of Transportation by IBI Group with LTK Engineering June 2009 This study is partially funded by the US Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. IBI GROUP PORtlAND UNION STATION MultIMODAL CONceptuAL ENGINeeRING StuDY IBI Group is a multi-disciplinary consulting organization offering services in four areas of practice: Urban Land, Facilities, Transportation and Systems. We provide services from offices located strategically across the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. JUNE 2009 www.ibigroup.com ii Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................... ES-1 Chapter 1: Introduction .....................................................................................1 Introduction 1 Study Purpose 2 Previous Planning Efforts 2 Study Participants 2 Study Methodology 4 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .........................................................................6 History and Character 6 Uses and Layout 7 Physical Conditions 9 Neighborhood 10 Transportation Conditions 14 Street Classification 24 Chapter 3: Future Transportation Conditions .................................................25 Introduction 25 Intercity Rail Requirements 26 Freight Railroad Requirements 28 Future Track Utilization at Portland Union Station 29 Terminal Capacity Requirements 31 Penetration of Local Transit into Union Station 37 Transit on Union Station Tracks -

Intercity Bus Transportation System and Its Competition in Malaysia

Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.8, 2011 Intercity Bus Transportation System and its competition in Malaysia Bayu Martanto ADJI Angelalia ROZA PhD Candidate Masters Candidate Center for Transportation Research Center for Transportation Research Faculty of Engineering Faculty of Engineering University of Malaya University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Fax: +603-79552182 Fax: +603-79552182 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Raja Syahira RAJA ABDUL AZIZ Mohamed Rehan KARIM Masters Candidate Professor Center for Transportation Research Center for Transportation Research Faculty of Engineering Faculty of Engineering University of Malaya University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Fax: +603-79552182 Fax: +603-79552182 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract : Intercity transportation in Malaysia is quite similar to other countries, which involve three kinds of modes, namely, bus, rail and air. Among these modes, bus transportation continues to be the top choice for intercity travelers in Malaysia. Bus offers more flexibility compared to the other transport modes. Due to its relatively cheaper fare as compared to the air transport, bus is more affordable to those with low income. However, bus transport service today is starting to face higher competition from rail and air transport due to their attractive factors. The huge challenge faced by intercity bus transport in Malaysia is the management of its services. The intercity bus transport does not fall under one management; unlike rail transport which is managed under Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad (KTMB), or air transport which is managed under Malaysia Airports Holdings Berhad (MAHB). -

Southwest Johnson County Transit Plan

Southwest Johnson County Transit Plan Prepared for: January 2018 Prepared by: TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 | INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................. 1 Plan Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................................................1 Existing Transit Service ...............................................................................................................................................................1 Document Review ........................................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 | NEEDS ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................................ 6 Employment and Travel Pattern Analysis ...............................................................................................................................6 Transportation Disadvantaged Population Analysis .......................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 3 | PUBLIC AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT ...................................................................... 15 Phase 1: Planning Kick-Off ...................................................................................................................................................... -

A Comparative Analysis of High-Speed Rail Station Development Into Destination and Multi-Use Facilities: the Case of San Jose Diridon

MTI A Comparative Analysis of Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 High-Speed Rail Station Transportation and California Department of Transportation Development into Destination and Multi-Use Facilities: The Case of San Jose Diridon MTI ReportMTI 12-02 December 2012 MTI Report 12-75 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER LEAD UNIVERSITY OF MNTRC Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation MTI/MNTRC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2019) Richard A. White (Ex-Officio) Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to Mineta (Ex-Officio) Chief Executive Officer Principal and Chair of Board Interim President and CEO be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Lea+Elliot, Inc. American Public Transportation Transportation Association (APTA) Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Vice Chair -

Rail Station Usage in Wales, 2018-19

Rail station usage in Wales, 2018-19 19 February 2020 SB 5/2020 About this bulletin Summary This bulletin reports on There was a 9.4 per cent increase in the number of station entries and exits the usage of rail stations in Wales in 2018-19 compared with the previous year, the largest year on in Wales. Information year percentage increase since 2007-08. (Table 1). covers stations in Wales from 2004-05 to 2018-19 A number of factors are likely to have contributed to this increase. During this and the UK for 2018-19. period the Wales and Borders rail franchise changed from Arriva Trains The bulletin is based on Wales to Transport for Wales (TfW), although TfW did not make any the annual station usage significant timetable changes until after 2018-19. report published by the Most of the largest increases in 2018-19 occurred in South East Wales, Office of Rail and Road especially on the City Line in Cardiff, and at stations on the Valleys Line close (ORR). This report to or in Cardiff. Between the year ending March 2018 and March 2019, the includes a spreadsheet level of employment in Cardiff increased by over 13,000 people. which gives estimated The number of station entries and exits in Wales has risen every year since station entries and station 2004-05, and by 75 per cent over that period. exits based on ticket sales for each station on Cardiff Central remains the busiest station in Wales with 25 per cent of all the UK rail network. -

High Speed Rail and Sustainability High Speed Rail & Sustainability

High Speed Rail and Sustainability High Speed Rail & Sustainability Report Paris, November 2011 2 High Speed Rail and Sustainability Author Aurélie Jehanno Co-authors Derek Palmer Ceri James This report has been produced by Systra with TRL and with the support of the Deutsche Bahn Environment Centre, for UIC, High Speed and Sustainable Development Departments. Project team: Aurélie Jehanno Derek Palmer Cen James Michel Leboeuf Iñaki Barrón Jean-Pierre Pradayrol Henning Schwarz Margrethe Sagevik Naoto Yanase Begoña Cabo 3 Table of contnts FOREWORD 1 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY 6 2 INTRODUCTION 7 3 HIGH SPEED RAIL – AT A GLANCE 9 4 HIGH SPEED RAIL IS A SUSTAINABLE MODE OF TRANSPORT 13 4.1 HSR has a lower impact on climate and environment than all other compatible transport modes 13 4.1.1 Energy consumption and GHG emissions 13 4.1.2 Air pollution 21 4.1.3 Noise and Vibration 22 4.1.4 Resource efficiency (material use) 27 4.1.5 Biodiversity 28 4.1.6 Visual insertion 29 4.1.7 Land use 30 4.2 HSR is the safest transport mode 31 4.3 HSR relieves roads and reduces congestion 32 5 HIGH SPEED RAIL IS AN ATTRACTIVE TRANSPORT MODE 38 5.1 HSR increases quality and productive time 38 5.2 HSR provides reliable and comfort mobility 39 5.3 HSR improves access to mobility 43 6 HIGH SPEED RAIL CONTRIBUTES TO SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 47 6.1 HSR provides macro economic advantages despite its high investment costs 47 6.2 Rail and HSR has lower external costs than competitive modes 49 6.3 HSR contributes to local development 52 6.4 HSR provides green jobs 57 -

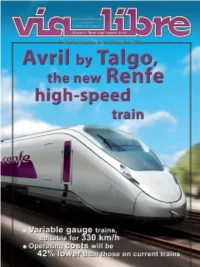

Avril by Talgo. the New Renfe High-Speed Train

Report - New high-speed train Avril by Talgo: Renfe’s new high-speed, variable gauge train On 28 November the Minister of Pub- Renfe Viajeros has awarded Talgo the tender for the sup- lic Works, Íñigo de la Serna, officially -an ply and maintenance over 30 years of fifteen high-speed trains at a cost of €22.5 million for each composition and nounced the award of a tender for the Ra maintenance cost of €2.49 per kilometre travelled. supply of fifteen new high-speed trains to This involves a total amount of €786.47 million, which represents a 28% reduction on the tender price Patentes Talgo for an overall price, includ- and includes entire lifecycle, with secondary mainte- nance activities being reserved for Renfe Integria work- ing maintenance for thirty years, of €786.5 shops. The trains will make it possible to cope with grow- million. ing demand for high-speed services, which has increased by 60% since 2013, as well as the new lines currently under construction that will expand the network in the coming and Asfa Digital signalling systems, with ten of them years and also the process of Passenger service liberaliza- having the French TVM signalling system. The trains will tion that will entail new demands for operators from 2020. be able to run at a maximum speed of 330 km/h. The new Avril (expected to be classified as Renfe The trains Class 106 or Renfe Class 122) will be interoperable, light- weight units - the lightest on the market with 30% less The new Avril trains will be twelve car units, three mass than a standard train - and 25% more energy-effi- of them being business class, eight tourist class cars and cient than the previous high-speed series. -

WEST COAST UPDATES Update: 1/14/2014

WEST COAST UPDATES Update: 1/14/2014 FIRST CLASS SHUTTLE is a Northern California airport shuttle carrier that has been added to the “Airport Links” list because their Redding – Red Bluff – Corning – Orland – Willows – Sacramento International Airport schedule meets the AIBRA website criteria. Their website is www.reddingfirstclassshuttle.com and their contact number is 1-530-605-0137. PORTER STAGE LINES (PSL) has operated scheduled service in Western Oregon for quite awhile. They now have their own website which is porterstageline.com and their contact number is 1-541-269-7183. OLYMPIC BUS LINES (OVT) has operated scheduled service in the Puget Sound area of Washington for a long time. Their scheduled service is also known as TRAVEL WASHINGTON DUNGENESS LINE which is now reflected in the AIBRA “Additional Information” list. Their website is www.olympicbuslines.com and their contact number is 1-360-417-0700. Additional updates are as follows: The AIBRA “Additional Information” list has been updated to reflect that the BARONS BUS LINE (BSB) service area includes Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania and West Virginia in addition to Ohio, and that MILLER TRANSPORTATION COMPANY (MTC) also serves Illinois. The AIBRA “Contact Us” email address has been changed to [email protected] The AIBRA website has been updated to reflect the above changes. SIGNIFICANT UPDATES IN THE MIDWEST (MOSTLY INDIANA) Update: 1/30/2014 BARONS BUS LINES and MILLER TRANSPORTATION COMPANY now have two schedules apiece between Chicago and Columbus, -

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

21NET:Broadband to Trains

Broadband to Trains AGENDA •Original ARTES project (2004-2006) in which we demonstrated first implementation of high speed internet over satellite on a high speed train (Renfe), and then a commercial trial (Thalys); •followed by a review of the developments we have undertaken since then focusing on our implementation on the Italian second railway operator NTV; •and lastly a summary of the challenges ahead to improve performance (VPNs, improved modems), bandwidth and antennas ARTES Workshop 1 Rome April 2013 Original ARTES Broadband to Trains Project Event Date Month Original Plan Kick Off 9 Feb 2004 0 0 BDR 31 Mar 2004 2 1 PSV 4 Nov 2004 9 6 SDA 18 Apr 2005 14 7 FR 6 Feb 2006 24 15 Broadband To Trains ESA Final Review 2 6 February 2006 Technical Trials in Spain - 2004 High Speed Internet for High Speed Trains 21Net + Renfe AVE PilotBroadband Trials To Trains ESA Final- June Review 3 6 February 2006 2004 Renfe Control Coach Broadband To Trains ESA Final Review 4 6 February 2006 Broadband To Trains ESA Final Review 5 6 February 2006 25,000 Volt Cable! Broadband To Trains ESA Final Review 6 6 February 2006 World Firsts We believe that 21Net / Renfe’s pilot trials represent: World’s first demonstration of high speed internet access from a high speed train World’s first demonstration of bi-directional Ku band satellite communication to and from a train Receive Data Rate: 4 mbps Transmit Date Rate: 2 mbps Broadband To Trains ESA Final Review 7 6 February 2006 Commercial Pilot on Thalys - 2005 High Speed Internet for High Speed Trains 21Net + Thalys CommercialBroadband To Trains ESA Service Final Review 8 - 6 February 2006 April - Dec 2005 "Everyone is eager to begin accessing the Internet onboard trains. -

8.4 Peer Review of Regional Bus Funding Programs

8 Funding Programs This chapter discusses the federal and state funding programs available for regional bus services, then provides a review of the use of funding by carriers in other states. 8.1 Federal Intercity Bus Operating Assistance—Section 5311(f) The Bus Regulatory Reform Act enacted in 1982 granted intercity bus operators much greater leeway in eliminating or adding service than they had been given under previous regulatory acts, some dating from the 1930s. By 1991, intercity bus service in in many rural, non-urbanized areas had been reduced significantly. In response, the multi-year federal authorization enacted that year, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), included a provision in Section 18(i) for financial assistance for maintaining or expanding intercity bus service in non-urbanized areas. Section 18 of ISTEA became Section 5311 in the next authorization, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), enacted in 1998. The Section 5311 designation has continued through subsequent authorizations, and provides for federal funding for transit services in non-urbanized and rural areas with populations less than 50,000. Funding nationwide is allotted to the states for distribution by state officials to local applicants. The funding allocation by state is based on each state’s non-urbanized population. Section 5311 funds can be used for capital expenditures, as well as operating, planning, or administrative expenses. Eligible recipients of Section 5311 funding include state agencies, local -

Intercity Bus Feeder Project Program Analysis

Intercity Bus U.S. Department of Transportation Feeder Project Program Analysis September 1990 Intercity Bus Feeder Project Program Analysis Final Report September 1990 Prepared by Frederic D. Fravel, Elisabeth R. Hayes, and Kenneth I. Hosen Ecosometrics, Inc. 4715 Cordell Avenue Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3016 Prepared for Community Transportation Association of America 725 15th Street NW, Suite 900 Washington, D.C. 20005 Funded by Urban Mass Transportation Administration U.S. Department of Transportation 400 Seventh Street SW Washington, D.C. 20590 Distributed in Cooperation with Technology Sharing Program Research and Special Programs Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C. 20590 DOT-T-91-03 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE s uh4h4ARY . S-l Background and Purpose ............................................. S-l CurrentStatusoftheProgram ......................................... S-3 Identification of Participant Goals ....................................... S-3 Analysis of Participants .............................................. S-8 casestudies ...................................................... s-11 Program Costs and Benefits ........................................... S-l 1 Conclusions ...................................................... S-13 Goals and Objectives for the Rural Connection ............................. S-15 Identification of Potential Future Changes ................................. S-17 1 -- INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OFTHE PROBLEM . 1 BackgroundandPurpose.............................................