Signs and Symbols Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caledonii Grande Tradition Greetings from the Editorial Staff

amildanachamildanach Journal of Celtic Studies ◊ Caledonii Grande Tradition SS http://www.angelfire.com/sc/Caledonii/ Premiere Edition ◊ Five dollars Greetings from the Editorial Staff It has been several years since the We are striving to present articles Sabbats, Gods and Goddesses of publication of the original Samildanach of worth to those of you who wish the Celts and customs relating to was released. Now, with new to be enriched in your study of them. We invite you to submit your computers and a full Staff comprised Celtic life ways. We’ll also carry articles to our Editorial Staff at least of hard working Caledonii members, sections announcing upcoming six weeks before the release date we hope to bring you this magazine Gatherings around the South East, for each issue. Issues of the zine will of Celtic Studies. You’ll find a lot in and notable Gathers throughout number four a year to correspond this issue which we hope will be of the States; as well as, articles on the to the great Fire Festivals. interest to you. – Continued on page 2 The Caledonii Grande Tradition A Little Background Grande Tradition known as the Wiccans and Mystic Christians can Fellowship of Caledon. In its come together and affirm their By Lord Ariel Morgan meetings, the Druidh, the Elders interconnectedness as Creators Ard Druidh Chosen Chief of the Order and Third Degree, and the Episcopacy, children and as brothers and sisters Wisdom Keeper of the Tradition sit together and create the policies of the Caledonii family. Within the which govern the Caledonii. -

On the Topology of Celtic Knot Designs

On the Topology of Celtic Knot Designs Gwen Fisher Mathematics Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 [email protected] Blake Mellor Mathematics Department Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, CA 90045-2659 [email protected] Abstract We derive formulas for counting the number of strands in a variety of knotwork designs inspired by traditional Celtic designs, including rectangular panels, circular borders, rectangular borders, and half frames. We include graphic examples for each of these types of designs. 1. Introduction There is a long tradition of abstract geometric designs in the art of the Celtic peoples of ancient Britain, Scotland and Ireland, including spirals, key patterns and, in the Christian era, knots and interlacings [1]. Complex knotwork patterns were used profusely in the Celtic illuminated manuscripts, such as in the Books of Durrow (early 5th to early 6th century), Kells (middle 6th to early 8th century), Lindesfarne (late 7th century), and Grimbald of St. Bertin (early 11th century). In these manuscripts, interlacing designs (both purely geometric, as in Figure 1, and incorporating animal figures) fill areas and are used as borders for text and illustrations. Françoise Henry called these designs a “sacred riddle” [7], and their symbolic meaning is a fascinating and unresolved issue in Celtic art history. James Trilling [10] has theorized that knotwork designs were, like the crosses that they commonly accompanied, protections against evil: the complex designs would trap and confuse the “evil eye”. Figure 1: A knotwork design, from [5] Whatever their meaning, the complexity of Celtic knotwork designs is evidence of substantial mathematical sophistication [4], and their design and analysis lead to many mathematical questions. -

MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!!

Make Your Plans for the Founder’s Day Cornroast and Family Picnic, on August 25th!!! ISSUE 16 / SUMMER ’12 Bill Parsons, Editor 6504 Shadewater Drive Hilliard, OH 43026 513-476-1112 [email protected] THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CALEDONIAN SOCIETY OF CINCINNATI In This Issue: Nature Smiles on KSW 1 MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!! Cornroast Aug 25th 2 *Schedule of Events 2 ust in case you did not attend the 30th Annual Kentucky Scottish Scotch Ice Cream? 3 JWeekend on the 12th of May, here CSHD 3 is what you missed. First off, a perfectly Cinti Highld Dancers 3 grand sunny day (our largest crowd Nessie Banned in WI 4 over the last three years); secondly, *Resource List 4 the athletics, Scottish country dancing, highland dancing, clogging, Seven Assessment KSW? 5 Nations, Mother Grove, the Border Scottish Unicorns 5 Collies, British Cars, Clans, and Pipe Glasgow Boys ’n Girls 6-11 Bands. This year we had a new group *Email PDF Issue only* called “Pictus” perform and we added a welly toss for the children. Colours Glasgow Girls 8* were posted by the Losantiville Scots on FIlm-BRAVE 12* Highlanders. Out of the Sporran 13* Food and drink. For the first time, the Park served beer and wine in the “Ole Scottish Pub”. Food vendors PAY YOUR DUES! included barbecue, meat pies, fish and Don’t forget to pay your current chips, gourmet ice cream, and bakery dues. You will not be able to vote goods galore. at the AGM unless your dues are Twelve vendors. From kilts to current. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

El Librofest Metropolitano 2016: Un Encuentro Con El Conocimiento

Vol. XXII • Núm. 39 • 06•06•2016 • ISSN1405-177X El Librofest Metropolitano 2016: un encuentro con el conocimiento Versión flip www.uam.mx/semanario/ UAM Comunicación www.facebook.com/UAMComunicacion En Portada Aviso a la comunidad universitaria Próxima sesión del Colegio Académico Con la participación de 60 editoriales y un vasto programa de actividades culturales se efectuó el 3er. Librofest Metropolitano 2016 de la UAM. Con fundamento en el artículo 42 del Regla- mento Interno de los Órganos Colegiados Si tienes algo Académicos, se informa que el Colegio Aca- démico llevará a cabo sus sesiones 397 y que contar 398, el 8 de junio próximo a partir de las 10:00 horas, en el segundo piso del Edificio o mostrar “H” de la Unidad Iztapalapa. compártelo con el Orden del día y documentación disponibles en: http://colegiados.uam.mx Transmisión: www.uam.mx/video/envivo/ [email protected] 5483 4000 Oficina Técnica del Colegio Académico Ext. 1523 Para más información sobre la UAM: Semanario de la UAM. Órgano informativo de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Unidad Azcapotzalco: Vol. XXII, Número 39, 6 de junio de 2016, es una publicación semanal editada Lic. Rosalinda Aldaz Vélez por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Prolongación Canal de Miramontes 3855, Jefa de la Oficina de Comunicación Col. Ex-Hacienda San Juan de Dios, Delegación Tlalpan, C.P. 14387, 5318 9519. [email protected] México, D.F.; teléfono 5483 4000, Ext. 1522. Rector General Unidad Cuajimalpa: Página electrónica de la revista: www.uam.mx/comunicacionsocial/semanario.html Lic. María Magdalena Báez Sánchez Dr. Salvador Vega y León dirección electrónica: [email protected] Coordinadora de Extensión Universitaria 5814 6560. -

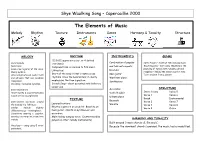

The Elements of Music

Skye Waulking Song – Capercaillie 2000 The Elements of Music Melody Rhythm Texture Instruments Genre Harmony & Tonality Structure MELODY RHYTHM INSTRUMENTS GENRE 12/8 (12 quavers in a bar, or 4 dotted Combination of popular Vocal melody: crotchets) Celtic Fusion – Scottish folk and pop music. Waulking song – work song. Waulking is the Pentatonic. Compound time is common to folk music. and folk instruments. Uses a low register of the voice. pounding of tweed cloth. Usually call and Lilting feel. Drum kit Mainly syllabic. response – helped the women work in time. Start of the song: hi-hat creates cross Alternates between Gaelic (call) Bass guitar Text is taken from a lament. and phrases that use vocables rhythms. Once the band enters it clearly Wurlitzer piano (response) emphasises the time signature. Synthesizer Vocables = nonsense syllables. Scotch Snap – short accented note before a longer one. STRUCTURE Instrumentalists: Accordion Short motifs & Countermelodies Violin (fiddle) Intro: 8 bars. Verse 5 Verse 1 Verse 6 based on the vocal phrases. Uileann pipes Break Instrumental TEXTURE Bouzouki Instruments improvise around Verse 2 Verse 7 Layered texture: the melody in a folk style. Whistle Verse 3 Verse 8 Rhythmic pattern on drum kit. Bass line on Similar melody slightly Verse 4 Outro bass guitar. Chords on synthesizer and different ways = heterophonic. Sometimes weaving a complex, accordion. weaving counterpoint around the Main melody sung by voice. Countermelodies HARMONY AND TONALITY melody. played on other melody instruments) Built around 3 main chords: G, Em and C. Vocal part = sung using E minor Because the dominant chord is avoided, the music has a modal feel. -

General Introduction the Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal (1895- 1896/97)

GENERAL INTRODUCTION THE EVERGREEN: A NORTHERN SEASONAL (1895- 1896/97) “Four seasons fill the measure of the year; There are four seasons in the mind of man.” Epigraph to The Evergreen, from John Keats’s “The Human Seasons” Evergreen flyleaf ornament. Published as a semi-annual by Patrick Geddes & Colleagues in the Lawnmarket of Edinburgh and by T. Fisher Unwin in London, The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal was produced out of interlacing connections as complex as those of the Celtic knot work it showcased. These include arts and crafts, Scottish Renascence, Pan-Celticism, and an urban renewal enhanced with what we would today call an ecological concern with nature and green space in the modern world. With local roots and international aspirations, The Evergreen sought to express a message of social regeneration by uniting art and science in the architecture of the page and the built environment. Expressed in Geddes’s triad of “sympathy, synergy, and synthesis,” this vision was embodied in the emblem of three flying black birds, each carrying a leaf in its beak, which decorated the openings of The Evergreen’s four volumes (Burbridge 73). As Regina Hewitt observes, Geddes conceptualized The Evergreen “as a resource for—and 1 perhaps even a manifesto of—cultural evolution” (“Patrick Geddes”). Although The Evergreen’s print run lasted less than two years, this innovative, interdisciplinary magazine had far-reaching impact. In his review for Pall Mall Magazine, Israel Zangwill highlighted the importance of the local and the social to this illustrated periodical. “’Till I went to Edinburgh,” he wrote, “I did not know what the ‘Evergreen’ was. -

Celtic Patterns to Colour Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CELTIC PATTERNS TO COLOUR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Struan Reid,David Thelwell | 32 pages | 01 Jul 2014 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9781409574651 | English | London, United Kingdom Celtic Patterns to Colour PDF Book You can learn more about how we plus approved third parties use cookies and how to change your settings by visiting the Cookies notice. There were Celts through most of Europe and even Asia, so these coloring sheets are Celtic favorites all over! Celtic Dogs Design. Knotted Celtic Art Design. Celtic Dublin. Triquetra Knot. Celtic Art Coloring Pages to Print. Cross Shape. Print all of our Celtic Coloring pages for free. Follow the lines. Patrick Celtic Coloring. Coloring pages. It can seem like a tangled maze, so some pre-thinking is in order for many of these coloring pages! Quad Celtic Knot. Copyright Disclaimer Disclosure Privacy Terms. Christmas Patterns to Colour Emily Bone. Also, get your favorite crayons, coloring pencils, and watercolors ready for my relaxing adult coloring pages! Trinity Celtic Triangle. Round Pattern. Accept all Manage Cookies. Celtic Heraldry. That's why there were so many intertwined animals, knots, vines, leaves and other decorations behind the main artwork. Celtic Knot Pattern. Swan Celtic Animals. Easy Celtic Bird. Designs are taken from stone carvings, pottery and jewellery and include the intricate knotwork patterns for which the Celts were famous. Vine Motif. Celtic Style Shamrock. Abigail Wheatley. Printable Celtic Symbol Coloring Pages. Beautiful Celtic Coloring Pages. Celtic Owl Design. Small Celtic Knots. They shared common languages, religious beliefs, traditions and of course artwork. Celtic Leaves. Celtic Triquetra Circle Interlaced. Dispatched from the UK in 1 business day When will my order arrive? Celtic Design. -

Thesis&Preparation&Appr

THESIS&PREPARATION&APPROVAL&FORM& & Title&of&Thesis:& Scottish&Fiddling&in&the&United&States:&Reviving&a&Tradition&and&Maintaining&a&Community& & & I. To&be&completed&by&the&Student:& & I&certify&that&this&document&meets&the&preparation&guidelines&as&presented&in&the& Style&Guide&and&Instructions&for&Preparing&Theses&and&Dissertations.&& & & _________________________________& &_______________& (Signature&of&Student)&& & (Date)& & & II. To&be&completed&by&thesis&advisor:& & I&certify&that&this&document&is&suitable&for&submission.& & & _________________________________&& _______________& (Signature&of&Advisor)&& & (Date)& & III. To&be&completed&by&School&Director:& & I&certify,&to&the&best&of&my&knowledge,&that&the&required&procedures&have&been& followed&and&the&preparation&criteria&have&been&met&for&this&thesis/dissertation.&& & & _________________________________& &_______________& (Signature&of&Director)&& & (Date)& & & xc:&Graduate&Coordinator& SCOTTISH FIDDLING IN THE UNITED STATES: REVIVING A TRADITION AND MAINTAINING A COMMUNITY A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Deanna T. Nebel May, 2015 Thesis written by Deanna T. Nebel B.M., Westminster College, 2013 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Jennifer Johnstone, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Ph.D., Acting Director, School of Music ____________________________________________________ -

Icons of the Iron Age: the Celts in History and Archaeology Course Guide

ICONS OF THE IRON AGE: THE CELTS IN HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COURSE GUIDE Professor Susan A. Johnston GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Icons of the Iron Age: The Celts in History and Archaeology Professor Susan A. Johnston George Washington University Recorded Books™ is a trademark of Recorded Books, LLC. All rights reserved. Icons of the Iron Age: The Celts in History and Archaeology Professor Susan A. Johnston Executive Producer John J. Alexander Executive Editor Donna F. Carnahan RECORDING Producer - David Markowitz Director - Matthew Cavnar COURSE GUIDE Editor - James Gallagher Design - Edward White Lecture content ©2008 by Susan A. Johnston Course guide ©2008 by Recorded Books, LLC 72008 by Recorded Books, LLC Cover image: Celtic knot design on a stone cross, Ballyroebuck, Ireland © Tom O’Brien/shutterstock.com #UT129 ISBN: 978-1-4361-5001-9 All beliefs and opinions expressed in this audio/video program and accompanying course guide are those of the author and not of Recorded Books, LLC, or its employees. Course Syllabus Icons of the Iron Age: The Celts in History and Archaeology About Your Professor...................................................................................................4 Introduction...................................................................................................................5 Lecture 1 The Creation of the Celts ......................................................................6 Lecture 2 The Documentary Sources..................................................................10 Lecture -

Celebrating the Celtic Imagination Midsummer 2008

Celebrating the Celtic Imagination Midsummer 2008 52 NEW Items! welcome to gaelsong Midsummer 2008 Midsummer night has always been a night for love magic…as the heat of the sun gives way to the cool of the evening, lovers meet in the enchanted air and make merry in song and dance all the night long. It is a time to envision the future and revel in the present. A walk through the dew on midsummer morn brings Colleen Connell, magical rewards, as we delight in the beauty of Founder the new day. At GaelSong, we hope to add beauty and magic to your life. We present beautiful gifts in the Celtic style, made all over the world. Many items we offer are hand-crafted by artisans devoted actual size to keeping traditional Celtic handiwork and design alive. Whether you seek wisdom by reflecting on the past or seek beauty and inspiration in the present, we hope our products will warm and enchant you. NEW! TRINITY KN O T BLOSSOM FAIRY HOUSES … A trinity knot and sparkling gem form an ever-flowering EV E RY W H ERE ! silver blossom on a delicate tendril of silver vine. Discover a world of Framed in sunny 14k gold or moonlight Sterling silver. whimsical habitats constructed from J1037 Trinity Knot Blossom Earrings, sterling $48 natural materials. J2055 Trinity Knot Blossom Pendant, sterling $48 Building diminutive J1042 Trinity Knot Blossom Earrings, houses from found 14k gold and sterling $248 materials (twigs, J2056 Trinity Knot Blossom Pendant, shells, pinecones and 14k gold and sterling $248 such) is a delightful pastime—and a sweet way to invite FLOWER FAIRIES the fairies. -

Who Were the Celts?

Who Were the Celts? The Celts were groups of people who lived in Europe during the Iron Age (800 BC-AD). The Iron Age was the period of time when iron replaced bronze in the making of tools and weapons. It was discovered that iron could be produced from iron ore in a process called smelting. Iron was harder than bronze so made better objects. Who Were the Celts? There were three main Celtic groups; the Gauls (in Northern mainland Europe), the Britons (in England) and the Gaels (in Ireland). Iron Age Celts lived in Britain and Ireland from 750 BC. Celts lived in tribes, each with their own king or queen. Celtic tribes, in what is now Britain, included the Iceni, the Cornovii and the Ordovices. The Celts ruled Britain until the Romans invaded in AD 43. Celtic Art Because the Celtic people lived all over Europe, Celtic art is varied. Some of it came in the form of stone carvings, jewellery, pottery, tools and other objects. “The Guard” by Patrimonio Nacional Galegois licensed under CC BY 2.0 “Image from page 379 of "The arts in early England" (1903)” “Celticy widdly-woo” by gajtalbot licensed under CC BY 2.0 “Glasnevin Cemetery” by William Murphy is licensed under CC BY 2.0 by Internet Archive Book Images is licensed under CC BY 2.0 How Do We Know About Celtic Art? There are only very limited records from the Celtic period so our knowledge of Celtic art comes from archaeology. This is the study of history through excavating sites and studying “Newgrange” by Sean MacEntee licensed under CC BY 2.0 artefacts and other remains.