West Yorkshire Bus Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GM Bus Reform Consultation PDF 2 MB

Public Document GREATER MANCHESTER HOUSING PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY DATE: Thursday, 11th June, 2020 TIME: 10.00 am VENUE: Microsoft Teams Meeting ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY AGENDA WITH ADDITIONAL MEETING PAPER 10. GM BUS REFORM CONSULTATION 1 - 34 Report by Kate Brown and Emma Flynn TfGM providing Members with an update on the approach, methodology and outputs of the Proposed Franchising Scheme following the public consultation close on 8 January 2020. This Supplementary agenda with Bus Reform Consultation was issued 05.06.20 on behalf of Julie Connor, Secretary to the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, Churchgate House, 56 Oxford Street, Manchester M1 6EU BOLTON MANCHESTER ROCHDALE STOCKPORT TRAFFORD BURY OLDHAM SALFORD TAMESIDE WIGAN Please note that this meeting will be livestreamed via www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk, please speak to a Governance Officer before the meeting should you not wish to consent to being included in this recording. This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 10 Housing, Planning & Environment Overview & Scrutiny Committee Date: Thursday 11 June 2020 Subject: Bus Reform Consultation Report of: GMCA Solicitor and Monitoring Officer PURPOSE OF REPORT Following the report to the Housing, Planning and Environment Overview and Scrutiny Committee on 23 September 2019, setting out the proposed approach to a consultation on a Proposed Franchising Scheme for Greater Manchester, this report provides an update on the approach, methodology and outputs of the consultation following its close on 8 January 2020. Reports on the outcome of the consultation process will be considered by Greater Manchester Combined Authority at its meeting on 26 June 2020 and comments or recommendations made by this Committee regarding the consultation process will be reported to that meeting. -

Notices and Proceedings for the North East of Englanf

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2363 PUBLICATION DATE: 22/03/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 12/04/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/03/2019 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Notices and Proceedings can be inspected free of charge at the Office of the Traffic Commissioner in Leeds. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Calderdale District Consultation

CALDERDALE DISTRICT CONSULTATION SUB-COMMITTEE MEETING TO BE HELD AT 5.00 PM ON TUESDAY 9 JANUARY 2018 IN THE MAIN HALL, THE KINGS CENTRE, HALIFAX, HX2 2TS A G E N D A 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2.2. ENCOURAGING YOUNG PEOPLE TO USE BUSES This will be a presentation provided by a representative from the West Yorkshire Combined Authority. 3.3. OPERATOR UPDATES This will be presented by representatives from the bus and rail operators. 4.4. MINUTES FROM THE MEETING HELD ON 10 OCTOBER 2017 Copy attached. (Pages 1 - 4) 5.5. INFORMATION REPORT This will provide the opportunity for questions to be raised from the floor with a focus on matters of wider interest. (Pages 5 - 10) 6.6. OPEN FORUM This will provide the opportunity for questions to be raised from the floor with a focus on matters of wider interest. This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 4 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE CALDERDALE DISTRICT CONSULTATION SUB-COMMITTEE HELD ON TUESDAY, 10 OCTOBER 2017 AT COMMITTEE ROOM B, TOWN HALL, CROSSLEY STREET, HALIFAX, HX1 1UJ Present: Councillor Daniel Sutherland (Chair) Transport Committee Councillor Peter Caffrey Transport Committee Reid Anderson (Public Representative) Public Representative Meg Gillet (Public Representative) Public Representative Myra James (Public Representative) Public Representative Zaheer Khalil (Public Representative) Public Representative Peter Melling (Public Representative) Public Representative John Myddelton (Public Representative) Public Representative John Sheppard (Public Representative) Public Representative Kate Smyth (Public Representative) Public Representative John Whiteley (Public Representative) Public Representative Geoff Wood (Public Representative) Public Representative In attendance: Mark Fenwick Arriva Yorkshire Councillor Paul Bellenger Calderdale Council Jenny Marshall Calderdale Council Peter Stubbs Calderdale Council Daniel Weir Calderdale Council Stuart Fillingham First Group Oliver Howarth First Group Pete Myers Northern Elliot Day Yorkshire Tiger Diane Groom WYCA Erica Ward WYCA Andrew Atack WYCA 1. -

Bus Service Motion Support Warwickshire County Council 30290C

Bus Service Motion Support Warwickshire County Council 30290C July 20 Final Quality Assurance Document Management Document Title Bus Service Motion Support Name of File 30290 REP Bus Service Motion Support.docx Last Revision Saved On 21/07/2020 16:18:00 Version V1 V2 V3 Final Prepared by MM/JP/JA/JG MM/JP/JA/JG/SH MM/JP/JA/JG/SH MM et al Checked by SH SW SW SW Approved by SH SH SH SW Issue Date 20/03/2020 22/04/2020 6/5/2020 21/7/2020 Copyright The contents of this document are © copyright The TAS Partnership Limited, with the exceptions set out below. Reproduction in any form, in part or in whole, is expressly forbidden without the written consent of a Director of The TAS Partnership Limited. Cartography derived from Ordnance Survey mapping is reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of HMSO under licence number WL6576 and is © Crown Copyright – all rights reserved. Other Crown Copyright material, including census data and mapping, policy guidance and official reports, is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland under licence number C02W0002869. The TAS Partnership Limited retains all right, title and interest, including copyright, in or to any of its trademarks, methodologies, products, analyses, software and know-how including or arising out of this document, or used in connection with the preparation of this document. No licence under any copyright is hereby granted or implied. Freedom of Information Act 2000 The TAS Partnership Limited regards the daily and hourly rates that are charged to clients, and the terms of engagement under which any projects are undertaken, as trade secrets, and therefore exempt from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act. -

Thematic Workshop a (UK) Lowcvp: UK Ebus Summit

Ref. Ares(2017)325830 - 20/01/2017 Thematic Workshop A (UK) LowCVP: UK eBus Summit 6.11 - Summary report of Thematic Workshop A (UK), current and future dissemination activities to promote the Deliverable eLIPTIC project aims, actions and outcomes to UK stakeholders in regards to the electrification of public transport in cities. Authors Dan Hayes, LowCVP Status (D: draft; F: final) F Document’s privacy PU (Public: PU; Private: PR) Hendrik Koch, City of Bremen; Reviewed by Wolfgang Backhaus, Rupprecht Consult; Yannick Bousse, UITP This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 636012. D6.11 Thematic Workshop A SUMMARY SHEET Programme Horizon 2020 Contract N. 636012 Project Title Electrification of public transport in cities Acronym ELIPTIC Coordinator Free Hanseatic City of Bremen Web-site http://www.eliptic-project.eu/ Starting date 1 June 2015 Number of months 36 months Deliverable N. 6.11 Deliverable Title Thematic Workshop Pillar A Milestones N/a Version V1 Date of issue 20-01-2017 Distribution [Internal/External] External Dissemination level [Public/ Confidential] Public Abstract The Thematic Pillar A Workshop was held on the 10th November 2016 in central London. The workshop was arranged by the LowCVP to disseminate the aims, objectives and current progress of the eLIPTIC project by M18 to UK stakeholders (local & national gov’t, transport operators, industry and public). Through LowCVP’s membership community and wider industry contacts over 50 delegates attended the workshop, with video recording used and shared via social media to further disseminate the Keywords Workshop, Dissemination, Pillar A, ELITPTIC, CITIVAS, Horizon2020, LowCVP, UK Critical risks This report is subject to a disclaimer and copyright. -

Sept 2020 All Local Registered Bus Services

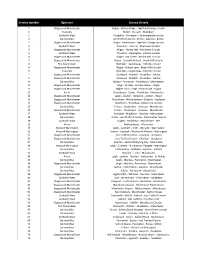

Service number Operator Service Details 1 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Marus Bridge - Highfield Grange Circular 1 Transdev Bolton - Darwen - Blackburn 1 Go North West Piccadilly - Chinatown - Spinningfields circular 2 Diamond Bus intu Trafford Centre - Eccles - Swinton - Bolton 2 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Pemberton - Highfield Grange circular 2 Go North West Piccadilly - Victoria - Deansgate circular 3 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Norley Hall - Kitt Green Circular 3 Go North West Piccadilly - Deansgate - Victoria circular 4 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Kitt Green - Norley Hall Circular 5 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Springfield Road - Beech Hill Circular 6 First Manchester Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 6 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Gidlow Lane - Beech Hill Circular 6 Transdev Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droyslden - Ashton 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droylsden - Ashton 8 Diamond Bus Bolton - Farnworth - Pendlebury - Manchester 8 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Hindley - Hindley Green - Wigan 9 Stagecoach Manchester Higher Folds - Leigh - Platt Bridge - Wigan 10 Arriva Brookhouse - Eccles - Pendleton - Manchester 10 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Lowton - Golborne - Ashton - Wigan 11 Stagecoach Manchester Altrincham - Wythenshawe - Cheadle - Stockport 12 Stagecoach Manchester Middleton - Boarshaw - Moorclose circular 15 Diamond Bus Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 15 Stagecoach Manchester Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 17 -

Notices and Proceedings 25 July 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2180 PUBLICATION DATE: 25 July 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 15 August 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 08/08/2014 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk Copies of Notices and Proceedings can be inspected free of charge at the Office of the Traffic Commissioner in Leeds. -

On Stage, Stagecoach Group, Stagecoach South West Mark Whittle 01392 889747 Operating Companies

Going topless Reaching a in New new level York of control The newspaper of Stagecoach Group Issue 54 Spring 2004 Stagecoach joins Danes in bid for rail franchise tagecoach Group has linked up with Danish State SRailways (DSB) to bid for a major UK rail franchise. Carry on The Group has taken a 29.9% majority of passenger rail services in stake in South Eastern Railways Ltd, a Denmark and has further franchise company set up by DSB, to bid for operations in other Scandinavian the new Integrated Kent franchise in countries. logging on south-east England. It is an independent Public Three other companies – GNER, Corporation, owned by the Danish Carry on megabus.com! First Group and a consortium of Go- Government, and is managed by a That was the message Ahead and Keolis, of France – have Board of Directors and an Executive from bubbly actress been shortlisted for the seven to 10- Committee, who are responsible for Barbara Windsor when year franchise. the day-to-day business. she helped launch Integrated Kent, which will be let Executive Vice President and CFO Britain’s first low-cost from early 2005, of DSB, Søren internet bus service. will include routes Eriksen said: And, with tickets on the national rail ‘Both Stagecoach “Stagecoach has available from just £1 network throug- extensive through megabus.com, the hout Kent, parts of and DSB share a experience with initiative is catching the Sussex and South- train operations in public’s imagination for East London. It will commitment to the UK and DSB is catching a bus. -

Leeds Bradford Airport - Harrogate Bus Service

LEEDS BRADFORD AIRPORT - HARROGATE BUS SERVICE LEEDS BRADFORD AIRPORT – HARROGATE BUS SERVICES Issue 1 SUMMARY This discussion paper outlines the history of bus services between Harrogate and Leeds Bradford Airport and then considers alternative ways in which the current 747 bus service between Harrogate and Bradford via Airport could be enhanced and made less dependent on subsidies. The current 60 minute frequency Harrogate-Airport-Bradford service operated by Centrebus between May 2011 and September 2013 and by Yorkshire Tiger since then is a significant improvement on the previous 90 minute frequency 767 Harrogate-Airport only service previously operated by Transdev from 2005 until 2011. However it is still not adequate in terms of frequency, reliability and operating hours. As the numbers of Airport passengers currently using the service appears insufficient to justify increasing the frequency and operating hours, it is vital that efforts are made to attract other fare-paying passengers to and from other places along the route. This paper suggests ten ways in which this might be achieved mostly at relatively little expense. With all Council funding under scrutiny following Government cuts, we cannot rely on the subsidy for these services and hence it is vital that they attract more income to be commercially viable. 1. HISTORY Harrogate Chamber was one of the original promoters of the need for this Bus Service as an important element of our Traffic & Transport Action Plan (HC361) - as illustrated by the fact that the official launch photograph in 2005 shows County Councillor John Fort, David Alexander, then MD of Transdev and Brian Dunsby in front of the first branded "Bus2Jet” outside the Airport. -

20354 LN CU 05 LGJ Vo B7R YV3R6G7265A106185 Pn

20354 LN CU 05 LGJ Vo B7R YV3R6G7265A106185 Pn 0512TLF6046 C45FL Aug-05 First Cymru (CW) 20354 Jun-07 allover white 20356 res CV 55 ABN Vo B7R YV3R6G7285A106186 Pn 0512TLF6047 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20356 Jun-07 2001 First Coach 20357 M CV 55 ABK Vo B7R YV3R6G7265A106607 Pn 0512TLF6049 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20357 Jun-07 allover white 20359 res CV 55 ACU Vo B7R YV3R6G72X5A106609 Pn 0512TLF6051 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20359 Jan-11 2001 First Coach 20361 LN CV 55 ACY Vo B7R YV3R6G7285A107824 Pn 0512TLF6053 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20361 Jan-11 2001 First Coach 20362 res CV 55 AFA Vo B7R YV3R6G72X5A107825 Pn 0512TLF6054 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20362 Feb-11 2001 First Coach 20363 LN CV 55 ACZ Vo B7R YV3R6G7215A107826 Pn 0512TLF6055 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20363 Jan-11 2001 First Coach 20364 res CV 55 AFE Vo B7R YV3R6G7255A107828 Pn 0512TLF6056 C45FL Sep-05 First Cymru (CW) 20364 Jun-07 2001 First Coach 20366 M CV 55 AFF Vo B7R YV3R6G7235A107830 Pn 0512TLF6059 C45FL Sep-05 Midland Bluebird (SE) 20366 Sep-12 20370 LN CV 55 AGY Vo B7R YV3R6G7205A108210 Pn 0512TLF6062 C45FL Sep-05 Midland Bluebird (SE) 20370 Sep-13 2001 First Coach 30829 w R649 HYG Vo OLY-56 YV3YNA412WC028923 Ar 9701/51 H43/29F Jul-98 Midland Bluebird (SE) 30829 Jan-14 2012 First 32221 LN LT 52 WUE Vo B7TL YV3S2G5133A002340 Pn 7962 H42/22F Nov-02 First Capital (LN) VNL32221 Sep-10 1997 First Primary 32222 M LT 52 WUG Vo B7TL YV3S2G5137A002342 Pn 7963 H42/22F Nov-02 First Capital (LN) VNL32222 Oct-10 2012 First 32223 M LT 52 WUH Vo B7TL YV3S2G5193A002357 -

Bdoy 2018 Score Sheet Final Version

BDoY Blackpool 2018 Scoresheet Competitor Name Company Final Position Competitor Number Country Designation TfL Left Tail Swing Bay Bus Right Tail Swing Front Separation Test Lay-By Bus Test Bicycle Stop Line StopBus 1 StopBus 2 Right Turn Prom KnowledgeDriver Total 1 39 Ian FIELD Stagecoach East Scotland SCO STA N 100 150 100 130 220 90 120 190 190 110 128 1528 2 80 Anthony QUINN Stagecoach West ENG STA N 100 160 120 130 250 50 120 210 140 70 160 1510 3 75 Raj VISWANATHAN Go-Ahead London ENG GA Y 70 150 120 110 250 60 120 160 190 110 160 1500 4 27 Nicholas GRAHAM First Hampshire, Dorset & Berkshire ENG FIR N 80 170 70 130 220 50 120 190 190 110 136 1466 5 7 Graham HALL Stagecoach South East ENG STA N 50 170 80 130 230 50 120 190 190 110 144 1464 6 21 Delfino GOUVEIA DE FREITAS RATP Dev London ENG RATP Y 60 150 50 130 220 90 120 170 210 110 152 1462 7 88 David WHITEHEAD Stagecoach East Midlands ENG STA N 80 160 80 130 220 90 120 180 170 110 120 1460 8 83 Stephen APPIAH Go-Ahead London ENG GA Y 80 210 50 130 220 90 120 160 190 110 96 1456 9 20 Steven MCLEOD Lothian Buses SCO ALB N 60 130 100 80 250 90 120 180 210 110 120 1450 10 64 Daniel BAINES Stagecoach Yorkshire ENG STA N 80 150 60 130 230 90 120 190 210 70 120 1450 11 60 Toni BRADLEY First Glasgow SCO FIR N 100 150 100 100 220 50 120 160 190 110 144 1444 12 5 Terence MILES RATP Dev London ENG RATP Y 100 130 80 130 220 50 120 180 190 110 128 1438 13 29 Glenn FOSTER First Cymru WAL FIR N 40 190 90 110 220 90 120 170 210 70 128 1438 14 10 Adam KSIAZEK First Aberdeen SCO FIR N 30 170 -

INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES WORKING

WORKING PAPER ITLS-WP-19-05 Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service By Rico Merkert, James Bushell and Matthew Beck Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies (ITLS), The University of Sydney Business School, Australia March 2019 ISSN 1832-570X INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES The Australian Key Centre in Transport and Logistics Management The University of Sydney Established under the Australian Research Council’s Key Centre Program. NUMBER: Working Paper ITLS-WP-19-05 TITLE: Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service Integrated mobility aims to improve multimodal integration to ABSTRACT: make public transport an attractive alternative to private transport. This paper critically reviews extant literature and current public transport governance frameworks of both macro and micro transport operators. Our aim is to extent the concept of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), a proposed coordination mechanism for public transport that in our view is yet to prove its commercial viability and general acceptance. Drawing from the airline experience, we propose that smart ticketing systems, providing Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) can be extended with governance and operational processes that enhance their ability to facilitate Collaboration-as-a-Service (CaaS) to offer a reimagined MaaS 2.0 = CaaS + SaaS. Rather than using the traditional MaaS broker, CaaS incorporates operators more fully and utilises their commercial self-interest to deliver commercially viable and attractive integrated public transport solutions to consumers. This would also facilitate more collaboration of private sector operators into public transport with potentially new opportunities for taxi/rideshare/bikeshare operators and cross geographical transport providers (i.e.