1999: Azerbajan Page 1 of 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azerbaijan National Survey of Voters February, 2003

Azerbaijan National Survey of Voters February, 2003 Presented by, Bill Cullo Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates - - Page 2 of 22 - - February, 2003 Methodology Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates is pleased to present the International Republican Institute (IRI) with the key findings of a survey of voter attitudes in Azerbaijan. Interviews were conducted among N=1,100 registered voters throughout the country February 15-March 5, 2003. Each interview was administered via person-to-person by a trained interviewer subcontracted through an Azeri research firm. Actual respondent selection for the study was at random using an “Nth” selection format. The number of interviews was distributed geographically using a pre-determined selection process to accurately reflect actual voter proportionality by zones throughout the country. The margin of error associated with a sample of this type is +2.9% at the 95% confidence interval. Meaning that if we conducted this same study administered in the same fashion that in 95 cases out of 100 the results would fall within +2.9% of these results. Project Objectives Most political survey projects are undertaken with multiple objectives or purposes. The Azeri project is no different in that the study was constructed to address three (3) primary objectives: 1. Gauge Political Landscape. Azerbaijan not receiving the healthy diet of surveys we do in the U.S. it was important to see how voters view their government; how voters receive the opposition parties; and where the issue matrix of voters is focused. 2. Aid the Opposition Parties. Anyone in Azerbaijan who decides to actively take part as a member of an opposition party has an extremely difficult road ahead of him. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Azerbaijan: Presidential Elections October 2003

AZERBAIJAN: PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS OCTOBER 2003 Report by Heidi Sødergren NORDEM Report 06/2004 Copyright: the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights/NORDEM and (author(s)). NORDEM, the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights, is a programme of the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights (NCHR), and has as its main objective to actively promote international human rights. NORDEM is jointly administered by NCHR and the Norwegian Refugee Council. NORDEM works mainly in relation to multilateral institutions. The operative mandate of the programme is realised primarily through the recruitment and deployment of qualified Norwegian personnel to international assignments, which promote democratisation and respect for human rights. The programme is responsible for the training of personnel before deployment, reporting on completed assignments, and plays a role in research related to areas of active involvement. The vast majority of assignments are channelled through the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. NORDEM Report is a series of reports documenting NORDEM activities and is published jointly by NORDEM and the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Series editor: Gry Kval Series consultants: Hege Mørk, Ingrid K. Ekker, Christian Boe Astrup The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher(s). ISSN: 1503–1330 ISBN: 82–90851–72-3 NORDEM Report is available online at: http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/publikasjonsliste.html Preface OSCE/ODIHR was invited by the Speaker of the Parliament of the Republic of Azerbaijan to observe the presidential elections that were to take place on 15 October 2003. The International Election Observation Missions (IEOM) was a joint undertaking of the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). -

The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan

Forschungsstelle Osteuropa Bremen Arbeitspapiere und Materialien No. 107 – March 2010 The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. A Background Study By Andreas Heinrich Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen Klagenfurter Straße 3, 28359 Bremen, Germany phone +49 421 218-69601, fax +49 421 218-69607 http://www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Arbeitspapiere und Materialien – Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen No. 107: Andreas Heinrich The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. A Background Study March 2010 ISSN: 1616-7384 About the author: Andreas Heinrich is a researcher at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen. This working paper has been produced within the research project ‘The Energy Sector and the Political Stability of Regimes in the Caspian Area: A Comparison of Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan’, which is being conducted by the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen from April 2009 until April 2011 with financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation. Language editing: Hilary Abuhove Style editing: Judith Janiszewski Layout: Matthias Neumann Cover based on a work of art by Nicholas Bodde Opinions expressed in publications of the Research Centre for East European Studies are solely those of the authors. This publication may not be reprinted or otherwise reproduced—entirely or in part—without prior consent of the Research Centre for East European Studies or without giving credit to author and source. © 2010 by Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen Forschungsstelle Osteuropa Publikationsreferat Klagenfurter Str. 3 28359 Bremen – Germany phone: +49 421 218-69601 fax: +49 421 218-69607 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................5 1. -

International Protection Considerations Regarding Azerbaijani Asylum-Seekers and Refugees

International Protection Considerations Regarding Azerbaijani Asylum-Seekers and Refugees United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Geneva September 2003 Department of International Protection 1 Protection Information Section TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 3 II. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 3 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ON AZERBAIJAN..................................................................... 3 1.1. General Information on Nagorno-Karabakh .................................................. 9 2. THE POLITICAL CONTEXT AND ACTORS SINCE 2001................................................... 10 2.1. Referendum, August 2002 ............................................................................. 12 2.2. Presidential Elections – October 2003, Outlook .......................................... 13 2.3. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Peace Initiatives Since 1999............. 14 2.4. Regional Implications ................................................................................... 20 2.5. Internally Displaced Persons........................................................................ 21 3. REVIEW OF THE GENERAL HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN AZERBAIJAN...................... 22 3.1. Freedom of Movement................................................................................... 24 3.2. Organized Crime.......................................................................................... -

Azerbaijan0913 Forupload 1.Pdf

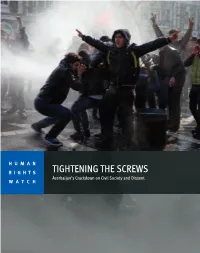

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Official Transcript.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 29, 2008 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 110–2–19] ( Available via http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63–897 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida, BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland, Chairman Co-Chairman LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin New York CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MIKE McINTYRE, North Carolina HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York HILDA L. SOLIS, California JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts G.K. BUTTERFIELD, North Carolina SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GORDON SMITH, Oregon ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MIKE PENCE, Indiana EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS DAVID J. KRAMER, Department of State MARY BETH LONG, Department of Defense DAVID BOHIGIAN, Department of Commerce (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN JULY 29, 2008 COMMISSIONERS Page Hon. -

In the Shadow of Revolution: a Decade of Authoritarian Hardening in Azerbaijan*

In the Shadow of Revolution: A Decade of Authoritarian Hardening in Azerbaijan* Cory Welt George Washington University [email protected] July 2014 WORKING PAPER * For citation as a working paper. 1 Over the last ten years, Azerbaijan’s ranking on the “democracy index” of the U.S.-based nongovernmental organization Freedom House has reflected the country’s slide from a “semi- consolidated” authoritarian regime to a “consolidated” authoritarian one.1 This change in regime type has not come suddenly. It has been the result of a gradual hardening of authoritarian governance since 2003, the year Ilham Aliyev became president. It might be difficult at first to grasp the significance of this shift in classification. Azerbaijan was hardly democratic under President Aliyev’s father, Heydar Aliyev, from 1993 to 2003. During the senior Aliyev’s rule, however, the regime allowed at least some freedom to civil society and media. Since then, the regime has become increasingly authoritarian across all indicators, but the collapse of space for nongovernmental forces to engage freely in the public sphere has been especially pronounced. Azerbaijan’s slide into consolidated authoritarianism has coincided with a decade of regime change from below in Azerbaijan’s two neighborhoods of post-Soviet Eurasia and the Middle East. From the color revolutions of 2003-2005 to the Arab Spring of 2010-2011 and Ukraine’s EuroMaidan of 2013-2014, the Azerbaijani government repeatedly has witnessed the fall of less consolidated authoritarian governments all around it. While it is difficult to determine precisely how much the power of these examples has contributed to Azerbaijan’s authoritarian hardening, a few connections are clear. -

Slussac WP Garnet SOCAR

The State as a (Oil) Company? The Political Economy of Azerbaijan∗ Samuel Lussac, Sciences Po Bordeaux GARNET Working Paper No. 74/10 February 2010 Abstract In 1993, Azerbaijan was a country at war, suffering heavy human and economic losses. It was then the very example of a failing country in the post-soviet in the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR. More than 15 years after, it is one of the main energy partners of the European Union and is a leading actor in the Eurasian oil sector. How did such a change happen? How can Azerbaijan have become so important in the South Caucasian region in such a short notice? This paper will focus on the Azerbaijani oil transportation network. It will investigate how the Azerbaijani oil company SOCAR and the Azerbaijani presidency are progressively taking over this network, perceived as the main tool of the foreign policy of Azerbaijan. Dealing with the inner dynamics of the network, this paper will highlight the role of clanic and crony capitalist structures in the makings of a foreign policy and in the diversification of an emerging oil company. Keywords: Azerbaijan, Network, Oil, South Caucasus, SOCAR. Address for correspondence: 42 rue Daguerre 75014 Paris Email: [email protected] ∗ The author is grateful to Helge Hveem and Dag Harald Claes for their valuable comments on previous versions of this research. This study has mainly been written during a research fellowship at the University of Oslo thanks to the generous support of GARNET (FP 6 Network of Excellence Contract n°513330). 1 Introduction Since 1991, Azerbaijan has drawn the energy sector’s attention, first for its oil reserves and now for its gas ones. -

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper October 31, 2005 Summary..................................................................................................................2 Background..............................................................................................................4 Past Elections ...................................................................................................... 5 Official Positions in the Lead-up to the 2005 Election Campaign ..........................6 Election Commissions .............................................................................................8 Voter Cards, IDs and Voter Lists.............................................................................8 Registration of Candidates.......................................................................................9 Media .....................................................................................................................10 Local Government Interference .............................................................................11 Candidates’ Meetings With Voters........................................................................11 Rallies ....................................................................................................................13 In the Capital, Baku........................................................................................... 13 In the Regions................................................................................................... -

The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. a Background Study

www.ssoar.info The formal political system in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan: a background study Heinrich, Andreas Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Heinrich, A. (2010). The formal political system in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan: a background study. (Arbeitspapiere und Materialien / Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen, 107). Bremen: Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-441356 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Statesmen and Public-Political Figures

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CONTENTS STATESMEN, PUBLIC AND POLITICAL FIGURES ........................................................... 4 ALIYEV HEYDAR ..................................................................................................................... 4 ALIYEV ILHAM ........................................................................................................................ 6 MEHRIBAN ALIYEVA ............................................................................................................. 8 ALIYEV AZIZ ............................................................................................................................ 9 AKHUNDOV VALI ................................................................................................................. 10 ELCHIBEY ABULFAZ ............................................................................................................ 11 HUSEINGULU KHAN KADJAR ............................................................................................ 12 IBRAHIM-KHALIL KHAN ..................................................................................................... 13 KHOYSKI FATALI KHAN ..................................................................................................... 14 KHIABANI MOHAMMAD ..................................................................................................... 15 MEHDİYEV RAMİZ ...............................................................................................................