Twlj. Volume 26, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007-08 Mgguide-CORRECTED.Qxd

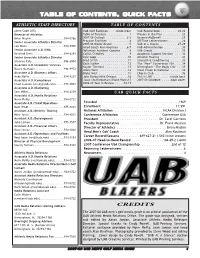

TABLE OF CONTENTS, QUICK FACTS ATHLETIC STAFF DIRECTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS (Area Code 205) UAB Golf Facilities . .inside front UAB Record Book . .20-22 Director of Athletics Table of Contents . .1 Players in the Pros . .22 Brian Mackin ..............................934-0766 2007-08 Outlook . .2-3 Graeme McDowell . .25 Senior Associate Athletics Director Practice Facilities . .4 All-Time Letterwinners . .26 2007-08 Blazer Roster . .5 UAB at a Glance . .27-29 Lee Moon..................................934-1900 Head Coach Alan Kaufman . .6-7 UAB Administration . .30 Senior Associate A.D./SWA Volunteer Assistant Coaches . .8 UAB Greats . .31 Rosalind Ervin ............................934-6283 Cathal O’Malley . .9 Academic Support Services . .32 Senior Associate Athletics Director Kyle Sapp . .10 Athletic Training . .33 Shannon Ealy .............................996-6004 Brad Smith . .11 Strength & Conditioning . .33 Zach Sucher . .12 The “New” Conference USA . .34 Associate A.D./Academic Services Kaylor Timmons . .13 Birmingham - The Magic City . .35 Danez Marrable ..........................996-9972 Adam West . .14 Shoal Creek Invitational . .36 Associate A.D./Business Affairs Blake West . .15 Chip-In Club . .36 Andy Hollis................................934-8221 John Darby/Mike Oimoen . .16 This is UAB . .inside back Associate A.D./Compliance Jason Shufflebotham/Blake Watts17 2007-08 Schedule . .back cover Chad Jackson ([email protected]) .......975-3051 2006-07 Year In Review . .18-19 Associate A.D./Marketing Sam Miller.................................934-1239 UAB QUICK FACTS Associate A.D./Media Relations Norm Reilly ...............................934-0722 Associate A.D./Ticket Operations Founded . .1969 Matt Wildt.................................975-8221 Enrollment . 17,591 Assistant A.D./Athletic Training National Affiliation . NCAA Division I Mike Jones ................................934-6013 Conference Affiliation . -

Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 37 2003 Reflections on ugusta:A Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness Scott R. Rosner Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Scott R. Rosner, Reflections on Augusta: Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness, 37 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 135 (2003). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol37/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REFLECTIONS ON AUGUSTA: JUDICIAL, LEGISLATIVE AND ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO PRIVATE RACE AND GENDER CONSCIOUSNESS Scott R. Rosner* In light of the recent controversy surrounding Augusta National Golf Club's exclusionary membership policy, this Article highlights the myriad incentives and disincentives that Augusta and similar clubs havefor reforming such policies. The author acknowledges the economic importance of club membership in many busi- ness communities and addresses the extent to which club members' claims of rights of privacy andfree association are valid. The Article also considers the potential of judicialaction in promoting the adoption of more inclusive membership policy; the state action doctrine and the First Amendment right to freedom of association are discussed as frameworks under which litigants may potentially bring claims against clubs and the author assesses the likelihood of success under each. -

No Women (And Dogs) Allowed: a Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Symposium on Regulatory Takings in Land-Use Law: A Comparative Perspective on Compensation Rights January 2007 No Women (and Dogs) Allowed: A Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England Eunice Song Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Eunice Song, No Women (and Dogs) Allowed: A Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England, 6 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 181 (2007), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol6/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NO WOMEN (AND DOGS) ALLOWED: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF DISCRIMINATING PRIVATE GOLF CLUBS IN THE UNITED STATES, IRELAND, AND ENGLAND INTRODUCTION In June 2005, Ireland’s High Court overruled a February 2004 landmark decision by district court Judge Mary Collins concerning sexual discrimination of women by private golf clubs in Ireland.1 Initially, Judge Collins ruled that the Portmarnock Golf Club,2 one -

History of Sport, Government and Golf in New Zealand

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. THE POLITICS OF SPORT FUNDING: AN ANALYSIS OF DISCOURSES IN NEW ZEALAND GOLF A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at The University of Waikato by TIDAVADEE TONGDETHSRI 2015 i Abstract In recent decades, the level of government intervention in sport has increased, involving greater resource allocations to community sport development, high performance sport and business capability initiatives. Within this context, sports organisations have faced increasing expectations around financial accountability and the need to provide professional governance and management. Increasing government intervention in sport has, however, not been matched by a growth in research, particularly into the way government involvement both reflects and contributes to changing understandings of the nature of sport and related changes to sports organisation that affect people’s opportunities to participate. -

1980-1989 Section History.Pub

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1980 to 1989 1980 The Section had another first as the new Senior PGA Tour held its first event at the Atlantic City CC in June. 1981 Dick Smith, Sr. won the 60 th Philadelphia PGA Section Championship at the Cavaliers Country Club in October. 1982 Dick Smith, Sr. won his fourth Philadelphia PGA Section Championship at Huntingdon Valley C.C. in September. 1983 Charlie Bolling won the South African Open in late January. 1984 Rick Osberg tied for third in the PGA Club Professional Championship in October. 1985 Ed Dougherty won the PGA Club Professional Championship in October. 1986 In December Dick Smith, Sr. was elected secretary of the PGA of America at the national meeting in Indianapolis. 1987 The Philadelphia pros defeated the Middle Atlantic Section to make it 12 wins for Philadelphia against 6 losses. 1988 The Philadelphia PGA Section Championship prize money was $100,000 for the first time. 1989 In April Jimmy Booros won on the PGA Tour at the Deposit Guaranty Golf Classic. 1980 A new decade began with golf booming. The PGA Tour purses were rapidly increasing and most of the tournaments were televised. There were concerns that there was too much golf being shown on TV. Playing the PGA Tour was a distant thought for most club pros. People were retiring earlier and more women were taking up the game so the rounds of golf were in- creasing each year. Senior golf was becoming very popular and the Phila- delphia Section was in on another first, as the Atlantic City Country Club would host the first official tournament of the new Senior PGA Tour. -

Pga Tour Book 1991

PGA TOUR BOOK 1991 Official Media Guide of the PGA TOUR nat l t rr' ~,Inllr, CJLF uHF PLAYLIi5 C I I - : PA)L SI IIP, I )L JHNlA.rv':L.N] I l l AY ERS CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAYERS CLUB, TPC, TPC INTERNATIONAL, WORLD SERIES OF GOLF, FAMILY GOLF CENTER, TOUR CADDY, and SUPER SENIORS are trade- marks of the PGA TOUR. PGA TOUR Deane R. Beman, Commissioner Sawgrass Ponte Vedra, Fla. 32082 Telephone: 904-285-3700 Copyright@ 1990 by the PGA TOUR, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced — electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopy- ing — without the written permission of the PGA TOUR. The 1990 TOUR BOOK was produced by PGA TOUR Creative Services. Al] text inside the PGA TOUR Book is printed on ® recycled paper. OFFICIAL PGA TOUR BOOK 1991 1991 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE CURRENT PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES 1990 TOURNAMENT RESULTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1991 PGA TOUR Tournament Schedule .....................................................4 Tournament Policy Board ..........................................................................11 Investments Board .....................................................................................12 Commissioner Deane R. Beman ...............................................................13 PGA TOUR Executive Department ............................................................14 Tournament Administration .......................................................................15 TournamentStaff ........................................................................................16 -

1 a Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and Its Members By

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1980 to 1989 1980 The Section had another first as the new Senior PGA Tour held its first event at the Atlantic City CC in June. 1981 Dick Smith, Sr. won the 60th Philadelphia PGA Section Championship at the Cavaliers Country Club in October. 1982 Dick Smith, Sr. won his fourth Philadelphia PGA Section Championship at Huntingdon Valley C.C. in September. 1983 Charlie Bolling won the South African Open in late January. 1984 Rick Osberg tied for third in the PGA Club Professional Championship in October. 1985 Ed Dougherty won the PGA Club Professional Championship in October. 1986 In December Dick Smith, Sr. was elected secretary of the PGA of America at the national meeting in Indianapolis. 1987 The Philadelphia pros defeated the Middle Atlantic Section to make it 12 wins for Philadelphia against 6 losses. 1988 The Philadelphia PGA Section Championship prize money was $100,000 for the first time. 1989 In April Jimmy Booros won on the PGA Tour at the Deposit Guaranty Golf Classic. 1980 A new decade began with golf booming. The PGA Tour purses were rapidly increasing and most of the tournaments were televised. There were concerns that there was too much golf being shown on TV. Playing the PGA Tour was a distant thought for most club pros. People were retiring earlier and more women were taking up the game so the rounds of golf were increasing each year. Senior golf was becoming very popular and the Philadelphia Section was in on another first, as the Atlantic City Country Club would host the first official tournament of the new Senior PGA Tour. -

For Immediate Release

On-site PGA TOUR media contact: Mark Stevens, Media Official (904) 861-5112 [email protected] 2015 Barbasol Championship pre-tournament notes Dates: July 13–19, 2015 Where: Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail at Grand National, Lake Course, Opelika/Auburn, Alabama Par/Yards: 35-36--7,302, par-71 Field: 132 2014 champion: inaugural event Purse: $3,500,000/$630,000 (winner) FedExCup: 300 points to the winner Format: 72-hole stroke play Website: www.barbasolchampionship.com Twitter: @BarbasolPGATOUR A look at the 2015 Barbasol Championship The Barbasol Championship will be the first PGA TOUR event in Alabama since the 1990 PGA Championship. With only eight events remaining before the FedExCup Playoffs, the Barbasol Championship will play an important role in the field for the first Playoffs event at The Barclays. The Barbasol Championship and the FedExCup Playoffs In 2014, it took 438 FedExCup points (No. 125/Robert Allenby) to qualify for the FedExCup Playoffs. Below are players in the field that are currently on “the bubble” for the FedExCup Playoffs: FedExCup Position Player FedExCup Points 120 Mark Wilson 391 123 Brian Stuard 377 124 Billy Hurley III 372 126 Scott Langley 365 128 Will Wilcox 358 129 Alex Prugh 353 130 Brice Garnett 352 132 Blayne Barber 345 134 Michael Thompson 339 135 Charlie Beljan 337 140 Ryo Ishikawa 321 A glance at the field: The highest-ranked player in the FedExCup standings is Scott Piercy (No. 42). Three former major championship winners: Trevor Immelman, Shaun Micheel, David Toms. The highest-ranked player in the Official World Golf Rankings is Emiliano Grillo at no. -

Country Club Discrimination After Commonwealth V. Pendennis Allison Lasseter

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 26 | Issue 2 Article 3 4-1-2006 Country Club Discrimination After Commonwealth v. Pendennis Allison Lasseter Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Taxation-State and Local Commons Recommended Citation Allison Lasseter, Country Club Discrimination After Commonwealth v. Pendennis , 26 B.C. Third World L.J. 311 (2006), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol26/iss2/3 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COUNTRY CLUB DISCRIMINATION AFTER COMMONWEALTH V. PENDENNIS Alison Lasseter* Abstract: In American country clubs, there is a long tradition of dis- crimination against racial minorities and women. These clubs maintain that they are private and thus able to operate free from government sanction. In 2004, the Supreme Court of Kentucky ruled that the state’s Commission on Human Rights had the statutory authority to investigate private country clubs to determine if they discriminate in their mem- bership practices. In Kentucky, if a club is found to discriminate, its members are disallowed certain tax deductions. While this is a step in the right direction to end discriminatory practices at country clubs, the Supreme Court of Kentucky still points out that private clubs have the right to discriminate without fear of legal liability. -

Tournament Fact Sheet Golf Course Management Information Course

Course statistics Average tee size: 1,000 sq. ft. 1421 Research Park Drive • Lawrence, KS 66049-3859 • 800- Tournament Stimpmeter: 13 ft. 472 -7878 • www.gcsaa.org Average green size: 6,500 sq. ft. Green construction soil mix: Tournament Fact Sheet USGA (sand 75%, peat 10%, other 15% ) Champions Tour Rounds per year: 14,000 Regions Tradition Acres of fairway: 50 Source of water: Pond, effluent water May 14 - 17, 2015 Acres of rough: 75 Drainage conditions: Fair Shoal Creek Golf Club Sand bunkers: 61 Shoal Creek, Ala. Water hazards: 11 Golf Course Management Championship ratings Information Yardage Par Rating Slope GCSAA Member Golf Course Superintendent: James K. Simmons 5 Star 7143 72 75.7 143 Availability to media: Contact James Simmons by phone 205-991- Course characteristics 9012; or email [email protected] Height of Primary Grasses Education: Cut Turfgrass Management, Michigan State Diamon University, East Lansing, Mich., 1971 Tees zoysiagrass; Zorro 0.35" Age: 65 zoysiagrass Native hometown: Fairways Bermudagrass 0.40" Marysville, Ohio Years as a GCSAA member: 43 Greens Bentgrass 0.110" GCSAA affiliated chapter: Bermudagrass; Rough 1.5" Alabama Golf Course Superintendents zoysiagrass Association Years at this course: 39 Number of employees: 20 Number of tournament volunteers: 25 Environmental Previous positions: management/features 1972-1975, Assistant Superintendent, Muirfield Village Golf Club, Dublin, Ohio; Water conservation, management and/or 1971, Assistant Superintendent, controls: Brookside Country Club, Worthington, Ohio; 1969, Intern, NCR Country Club, Shoal Creek Golf Club installed a new Toro Kettering, Ohio Lynx irrigation system to help monitor and Previous tournaments hosted by facility: control water usage. -

'Ga Tour Book 992

'GA TOUR BOOK 992 cial Media Guide of the PGA TOUR I PGA PGA TOUR, SENIOR PGA TOUR, SKINS GAME, STADIUM GOLF, THE PLAYERS CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAYERS CHAMPIONSHIP, THE TOUR CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAYERS CLUB, TPC, TPC INTERNA- TIONAL, WORLD SERIES OF GOLF, FAMILY GOLF CEN- TER, TOUR CADDY, and SUPER SENIORS are trademarks of the PGA TOUR. PGA TOUR Deane R. Beman, Commissioner Sawgrass Ponte Vedra, Fla. 32082 Telephone 904-285-3700 Copyright,, 1991 by the PGA TOUR, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be repro- duced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying - without the written permission of the PGA TOUR. The 1992 TOUR BOOK was produced by PGA TOUR Creative Services. Alltextinsidethe PGATOUR Book is printed on recycled paper. OFFICIAL PGA TOUR BOOK 1992 1992 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE CURRENT PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES 1991 TOURNAMENT RESULTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1992 PGA TOUR Tournament Schedule ....................... ..............................4 Tournament Policy Board ............................................. .............................11 Investments Board ........................................................ .............................12 Commissioner Deane R. Beman ..............._................. .............................13 PGA TOUR Executive Department ............................... .............................14 Tournament Administration ..................................................._..................15 Finance and Legal Departments ................................... -

Crooked Stick Golf Course Superintendent Profile

Shoal Creek Club Manager Profile Shoal Creek was founded in 1977 and is located 20 minutes from downtown Birmingham, Alabama. Shoal Creek was Jack Nicklaus first solo design project. The Club is viewed as one of the premier golf clubs in the Southeast. Since the clubs inception it was consistently been voted in numerous publications as a top 100 golf course. The club has hosted 10 major championships to include the following • 1984 and 1990 PGA Championship • 1986 U.S. Amateur • 2008 U.S. Junior Amateur • 2011-2015 Regions Tradition • 2018 U.S. Women’s Open Shoal Creek by the numbers • There are 550 total members o Robust National Membership, over 150 memberships which contribute 60% total operating revenue • Current Initiation Fees o Full Equity Membership – 60k o National-30k • 18 holes of championship golf. Jack Nicklaus first solo design. 13k rounds annually. • 9 hole Little Links course • 3 acre short game practice park • 2 bay indoor Gene Sarazen Teaching Facility • 1 Swimming Pool(Memorial Day-Labor Day) • Small Fitness Center(no staffing required) • 44 overnight rooms on property between 6 cottages-550k annual revenue • Overall operating budget is approximately $6M • Food and beverage volumes are approximately $1.0M, with approximately 60% coming from member dining • Approximately 6 department heads, another 55 full time staff and another 50 part time staff members during the heights of our busy season • There are 16 Board Members, each serving two consecutive two year terms • There are 4 standing committees, golf, house, finance, membership. • This position reports to the club president • While the club is open year round we have very heavy utilization in the spring and fall seasons with increased national membership visits.