Marib Governorate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tor Yemen Nutrition Cluster Revi

Yemen Nutrition Cluster كتله التغذية اليمن https://www.humanitarianresponse.info https://www.humanitarianresponse.info /en/operations/yemen/nutrition /en/operations/yemen/nutrition XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX YEMEN NUTRITION CLUSTER TERMS OF REFERENCE Updated 23 April 2018 1. Background Information: The ‘Cluster Approach1’ was adopted by the interagency standing committee as a key strategy to establish coordination and cooperation among humanitarian actors to achieve more coherent and effective humanitarian response. At the country level, the aim is to establish clear leadership and accountability for international response in each sector and to provide a framework for effective partnership and to facilitat strong linkages among international organization, national authorities, national civil society and other stakeholders. The cluster is meant to strengthen rather than to replace the existing coordination structure. In September 2005, IASC Principals agreed to designate global Cluster Lead Agencies (CLA) in critical programme and operational areas. UNICEF was designated as the Global Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency (CLA). The nutrition cluster approach was adopted and initiated in Yemen in August 2009, immediately after the break-out of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. These complex emergencies have come on the top of an already fragile situation with widespread poverty, food insecurity and underdeveloped infrastructure. Since mid-March 2015, conflict has spread to 20 of Yemen’s 22 governorates, prompting a large-scale protection crisis and aggravating an already dire humanitarian crisis brought on by years of poverty, poor governance and ongoing instability. -

Camels, Donkeys and Caravan Trade: an Emerging Context from Baraqish

Camels, donkeys and caravan trade: an emerging context from Baraqish,- ancient Yathill (Wadi- - al-Jawf, Yemen) Francesco G. FEDELE Laboratorio di Antropologia, Università di Napoli ‘Federico II’, Naples, Italy (retired), current address: via Foligno 78/10, 10149 Torino (Italy) [email protected] Fedele F. G. 2014. — Camels, donkeys and caravan trade: an emerging context from Bara¯qish, ancient Yathill (Wa-di al-Jawf, Yemen). Anthropozoologica 49 (2): 177-194. http:// dx.doi.org/10.5252/az2014n2a02. ABSTRACT Work at Barāqish/Yathill in 2005-06 has produced sequences encompassing the Sabaean (13th-6th centuries BC) and Minaean/Arab (c. 550 BC-AD 1) occupa- tions. Abundant animal remains were retrieved and contexts of use and discard were obtained. Camels and donkeys are studied together as pack animals, the camel being the domestic dromedary. Their zooarchaeological and contextual study at Yathill is justified from this city’s location on the famous frankincense caravan route of the 1st millennium BC. An extramural stratigraphic sequence documenting the relationships between the city and the adjoining plain from c. 820 BC to the Islamic era was investigated to the northwest of the Minaean KEY WORDS wall. Domestic camels were present by 800 BC, the earliest well-documented Dromedary (Camelus occurrence in Yemen; wild dromedary herds were still in the area during the dromedarius), Camelus sp. wild, 7th century and perhaps later. The study of the archaeological context links donkey (Equus asinus), these Sabaean-age camels to campsites possibly formed by non-residents. This caravan trade, archaeological indicators pattern greatly developed during the Minaean period, with trade-jar handling of ‘caravan’ activity, posts outside the walled city and frequent stationing of camels and donkeys on ‘frankincense route’ in the upper talus. -

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Aden Sub- Office May 2020

FACT SHEET Aden Sub- Office May 2020 Yemen remains the world’s Renewed fighting in parts of UNHCR and partners worst humanitarian crisis, with the country, torrential rains provide protection and more than 14 million people and deadly flash floods and assistance to displaced requiring urgent protection and now a pandemic come to families, refugees, asylum- assistance to access food, water, exacerbate the already dire seekers and their host shelter and health. situation of millions of people. communities. KEY INDICATORS 1,082,430 Number of internally displaced persons in the south DTM March 2019 752,670 Number of returnees in the south DTM March 2019 161,000 UNHCR’s partner staff educate a Yemeni man on COVID-19 and key Number of refugees and asylum seekers in the preventive measures during a door-to-door distribution of hygiene material south UNHCR April 2020 including soap, detergent in Basateen, in Aden © UNHCR/Mraie-Joelle Jean-Charles, April 2020. UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 85 National Staff 14 International Staff Offices: 1 Sub Office in Aden 1 Field Office in Kharaz 2 Field Units in Al Mukalla and Turbah www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Aden Sub- Office/ May 2020 Main activities Protection INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS Protection Cluster ■ The Protection Cluster led by UNHCR and co-led by Intersos coordinates the delivery of specialised assistance to people with specific protection needs, including victims of violence and support to community centres, programmes, and protection networks. ■ At the Sub-National level, the Protection Cluster includes more than 40 partners. ■ UNHCR seeks to widen the protection space through protection monitoring (at community and household levels) and provision of protection services including legal, psychosocial support, child protection and prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence. -

Tribes and Politics in Yemen

Arabian Peninsula Background Notes APBN-007 December 2008 Tribes and Politics in Yemen Yemen’s government is not a tribal regime. The Tribal Nature of Yemen Yet tribalism pervades Yemeni society and influences and limits Yemeni politics. The ‘Ali Yemen, perhaps more than any other state ‘Abdullah Salih regime depends essentially on in the Arab world, is fundamentally a tribal only two tribes, although it can expect to rely society and nation. To a very large degree, on the tribally dominated military and security social standing in Yemen is defined by tribal forces in general. But tribesmen in these membership. The tribesman is the norm of institutions are likely to be motivated by career society. Other Yemenis either hold a roughly considerations as much or more than tribal equal status to the tribesman, for example, the identity. Some shaykhs also serve as officers sayyids and the qadi families, or they are but their control over their own tribes is often inferior, such as the muzayyins and the suspect. Many tribes oppose the government akhdam. The tribes in Yemen hold far greater in general on grounds of autonomy and self- importance vis-à-vis the state than elsewhere interest. The Republic of Yemen (ROY) and continue to challenge the state on various government can expect to face tribal resistance levels. At the same time, a broad swath of to its authority if it moves aggressively or central Yemen below the Zaydi-Shafi‘i divide – inappropriately in both north and south. But including the highlands north and south of it should be stressed that tribal attitudes do Ta‘izz and in the Tihamah coastal plain – not differ fundamentally from the attitudes of consists of a more peasantized society where other Yemenis and that tribes often seek to tribal ties and reliance is muted. -

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf

Republic of Yemen Ministry of Public Health and Population Central Statistical Organization Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf Governorate, Yemen From 19 to 25 April 2018 1 Acknowledgment The Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen, represented by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate and in cooperation with the UNICEF country office in Yemen and the UNICEF branch in Sana’a, acknowledges the contribution of different stakeholders in this survey. The UNICEF country office in Yemen provided technical support, using the SMART methodology, while the survey manager and his assistants from the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Public Health and Population Offices in Amran and Taiz were also relied on. The surveyors and team heads were provided by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate. The data entry team was provided by the Public Health and Population Office in Amran and the Nutrition Department in the Ministry. The survey protocol was prepared, and other changes were made to it, through cooperation between the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Central Statistical Organization, with technical support from UNICEF. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development provided UNICEF with technical assistance, especially with regards to daily quality checks, data analysis, and report writing. The Building Foundation for Development provided technical and logistical support through extensive coordination with the local authorities in the Al Jawf governorate, as well as through their choice of the survey team and providing extensive training for them. The Building Foundation for Development was also responsible for regular follow-up with the survey teams out in the field and providing logistical and technical support for these teams, as well as preparing the initial draft of the survey report. -

June 2013 - February 2014

Yemen outbreak June 2013 - February 2014 Desert Locust Information Service FAO, Rome www.fao.org/ag/locusts Keith Cressman (Senior Locust Forecasting Officer) SAUDI ARABIA spring swarm invasion (June) summer breeding area Thamud YEMEN Sayun June 2013 Marib Sanaa swarms Ataq July 2013 groups April and May 2013 rainfall totals adults 25 50 100+ mm Aden hoppers source: IRI RFE JUN-JUL 2013 Several swarms that formed in the spring breeding areas of the interior of Saudi Arabia invaded Yemen in June. Subsequent breeding in the interior due to good rains in April-May led to an outbreak. As control operations were not possible because of insecurity and beekeepers, hopper and adult groups and small hopper bands and adult swarms formed. DLIS Thamud E M P T Y Q U A R T E R summer breeding area SEP Suq Abs Sayun winter Marib Sanaa W. H A D H R A M A U T breeding area Hodeidah Ataq Aug-Sep 2013 swarms SEP bands groups adults Aden breeding area winter hoppers AUG-SEP 2013 Breeding continued in the interior, giving rise to hopper bands and swarms by September. Survey and control operations were limited due to insecurity and beekeeping and only 5,000 ha could be treated. Large areas could not be accessed where bands and swarms were probably forming. Adults and adult groups moved to the winter breeding areas along the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden coasts where early first generation egg-laying and hatching caused small hopper groups and bands to DLIS form. Ground control operations commenced on 27 September. -

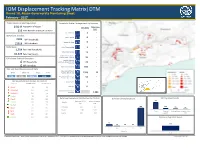

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017 Total Governorate Population Household Shelter Arrangements by Location 2 Population of Abyan 1 0.56 M IDPs (HH) Returnees (HH) 116 Total Number of Unique Locations School Buildings 2 - IDPs from Conflict Health Facilities 0 - 2103 IDP Households Religious Buildings 0 - 12618 IDP Individuals Returnees Other Private Building 5 - 1,754 Returnee Households Other Public Building 15 - 10,524 Returnee Persons Settlements (Grouped of Families) Urban and Rural - IDPs from Natural Disasters 24 Isolated/ dispersed IDP Households settlements (detatched from 26 - 0 a location) IDP Individuals 0 Rented Accomodation 650 - Sex and Age Dissagregated Data Host Families Who are Men Women Boys Girls Relatives (no rent fee) 1326 70 21% 23% 25% 31% Host Families Who are not Relatives (no rent fee) 54 - IDP Household Distribution Per District Second Home 1 - District IDP HH in Jan IDP HH in Feb Ahwar 32 29 Unknown 0 - Al Mahfad 379 264 Original House of Habitual Al Wade'a 110 96 Residence 1,684 Jayshan 15 25 Khanfir 505 499 Returnee Household Distribution Per District Duration of Displacement IDP Top Most Needs Returnee HH in Returnee HH in 79% Lawdar 259 278 District Jan Feb Mudiyah 34 35 Al Wade'a 130 130 92% 12% 6% Rasad 241 201 2% Khanfir 1,200 1,200 Sarar 121 114 Food Financial Drinking Water Household Items Lawdar 424 424 support (NFI) Sibah 248 221 Zingibar 221 341 Returnee Top Most Needs 8% 0% 0% 0% 100% 1-3 4-6 7-9 10-12 12 > Months Food 1 Population -

YEMEN: Humanitarian Snapshot (November 2013)

YEMEN: Humanitarian Snapshot (November 2013) Fifty eight per cent of Yemen’s population (14.7 million out of 25.2 million people) are affected by the humanitarian crisis and Internal displacement 3/4 will need assistance next year, the crisis is compounded by a lack of basic services, weak state authority and poor resource (Cumulative figures - 30 Oct 2013) management. 13 million people lack access to improved water sources, while 8.6 million lack access to basic health care. 306,964 IDPs There are also more than 500,000 IDPs, returnees and other marginalized people, and 242,944 refugees, mostly Somalis. 227,954 returnees Displaced/Returnees in 45%thousands Humanitarian Reponse Plan 2014 IDPs Identified Severe Needs Returnees 10 Food Security About 400,000 Yemeni migrant SAUDI ARABIA 306 307 306 307 307 307 5 OMAN 6 million moderately food insecure workers returned since April OMAN 232 232 233 228 228 228 4.5 million are severely food insecure May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct 72% of the total returnees (227,954) SAUDI ARABIA country-wide, are in the south. % of food- insecure people 103,014 > 75% 50.1% - 75% 25.1 - 50% SA'ADA Refugees and new <= 25% 7 Sa'adahDammaj AL JAWF Al Maharah 3 Nutrition No data 64,758 arrivals in 2013 779,000 children acutely malnourished 24,700 (Cumulative figures - October 2013) 279,000 children severely acutely Haradh 42,191 malnourished Al Ghaydah 242,944 Refugees (as of Oct 2013) Al Hazm 91 81,919 3 Al Ghaydah AMRAN Al Jawf Hadramaut 62,851 New arrivals (Jan-Oct 2013) HAJJAH AMANAT AL MAHARAH YEMEN Trend analysis