Edward T. Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Students Formul Ate Resumed by Bixler

I . R . C. To Discuss Happy Birthday The Big Three Dean Marriner VTTTTl,TT>T7»-D O Students Formul ate 52'Women/6 Men New Const itution Attain Dean 's List Men 's Student Council Men s Division Class of 1947 Powder And Wig Abandon War Documeat Initial - Discussion An open meeting of Powder Former Rhodes Scholar William Kershaw, Waterville, Maine and Wig is planned for Tuesday Bradley C. Maxim, Orono, Maine evening, October 16, at 7:15 in Studies Symbolist Poet By R. Rosen Of 1R. C Features Class of 1948 the Alumnae Building. All The Men's Student Council pro members of the club are invited Carl E. Chellquist, Boston, Mass. g Author Of. Literar y Criticism tempore met in the quiet seclusion of Panel On Bi Three to attend. Donald F. Klein, New York City Lounge last Wednesday night Smith Burton A. Krumholss, Brooklyn, N. Y. Teaches English And Histor y -jwrite the outmoded war constitu- • . Edward C. Schliek, Arlington, N. J. " 'The Big Three' : Concord or Dis- tion. cord" will be the topic of a panel dis- y Orchestra To Hold Colb Dr F. 0. Matthiessen opens the The highlights of the " constitution cussion at the opening meeting of the International Relations Club. This Pro gram on Januar y 27 1045-1946 season of Averill Lectures consists of liberal prerequisites for Women's Division with a talk on Edgar Allan Poe next tlie utilizing of initiative, referen- first meeting will be held on Tuesday Spring Term, 1944-45 evening, October 23 Friday evening. The lecture will be dum, and recall ; representation is to , at 7:45 in the Women's Union. -

Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular! Page 8

June 25–July 8, 2012 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE to BOSton PANORAMAEVSIGHTSENTS | | SHOPPING | MAPS | DINING | NIGHTLIFE | CULTURE Sparks fly at the BOSTON POPS FIREWORKS SpECTACULAR! page 8 A PEEK AT THE PAST BOSTON’S SKINNY HOUSE BOSTON COMEDY GET YOUR FUNNY ON Pano’s Guide tO BOSTon’s Hidden GEMS www.bostonguide.com raymond-weil.com freelancer collection automatic chronograph The Shops at Prudential Center Boston 617.262.0935 PanormaMag_RossSimon_RW_Freelancer_non.indd 1 5/7/12 11:44 AM June 25–July 8, 2012 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE TO BOSTON Volume 62 • No. 3 contents Features A 4th that Pops! 8 The Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular Now That’s Funny! 10 The Hub’s comedy scene A Peek at the Past 12 Boston’s Skinny House, plus the city’s best men’s shops PANO’s Guide to 8 14 Boston’s Hidden Gems Boston’s hard-to-find nightspots Departments 6 HUBBUB Ansel Adams in Salem, burger nirvana in Cambridge, Italian dining on the waterfront and more 16 Boston’s Official Guide 16 Current Events 10 24 On Exhibit 27 Shopping 34 Cambridge 39 Maps 45 Neighborhoods 52 Sightseeing 61 Freedom Trail 63 Dining 78 Back in Boston MFA Chef Tim Partridge ON THE COVER: The Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular. 14 MIDDLE PHOTO: DEREK KOUYOUMJIAN; BOTTOM PHOTO: DANIELLE ASHLEY BURKE BOSTONGUIDE.COM 3 ThE Official guidE to boston www.bostonguide.com June 25–July 8, 2012 Volume 62 • Number 3 Tim Montgomery • President/Publisher Samantha House • Editor Scott Roberto • Art Director Paul Adler • Associate Editor John Herron Gendreau • Associate Art Director Derek Kouyoumjian • Contributing Photographer Benjamin Lindsay • Staff Writer Kiana Sarabia Strayhorn • Editorial Intern Ze Sheng Liang, Danielle Ashley Burke • Photo Interns Rita A. -

VALENTINE's MANUAL of OLD NEW YORK

Gc 974.702 PUBLIC LIBRARY N421V PORT WAYNE 8c ALLEN CO., IND. 1921 301064 SenhaloC^Y collection 02210 3862 .sormy.. 3 1833 aii»ntittt^^Mnttual nf Copyrig-ht, 1920 Press of The Chauncey Holt Company New York City 101064 Ea tl)[f Spatnration nf ; !%[ aittg l^all fark nnh tire lErrrtian nf tijp CONTENTS Page FIFTH AVENUE AND CENTRAL PARK, 1858 9 A retrospective comment on a rare view of the locality. SPLENDORS OF THE BATTERY IN 1835 20 A contemporary description from the N. Y. Mirror. "FRIENDSHIP GROVE" AND ITS MEMORIES 21 Recollections of Commodore E. C. Benedict. IMMORTALITY, "THE BUTTERFLY POEM," by Joseph Jefferson.... 25 RECORD OF SKATING DAYS, 1872-1887 46 DIARY OF A LITTLE GIRL IN OLD NEW YORK (Continued).... 47 Catherine Elizabeth Havens. CURIOUS OLD LETTER TO MR. ZENGER 70 EDGAR ALLAN POE IN NEW YORK CITY 71 From hitherto unprintcd papers in the possession of the Shakes- peare Society, by Dr. Appleton Morgan, President. NEW LIBERTY POLE AND REMOVAL OF THE POST OFFICE BUILDING 86 Action taken by the New York Historical Society and the Sons of the Revolution. LIBERTY POLES ERECTED AND CUT DOWN 90 AMERICA'S CUP 90 Commodore J. C. Stevens' account of ihe yacht race at Cowes, 1851. DEED OF TRUST OF THE AMERICA'S CUP TO THE NEW YORK YACHT CLUB 94 POPULATION FIGURES OF NEW YORK CITY, 1615-1920 96 [xi] Page EARLY DAYS OF DEPARTMENT STORES 97 Incidents and characteristics of their beginnings and growth in New York and of the men who made them. John Crawford Brown. -

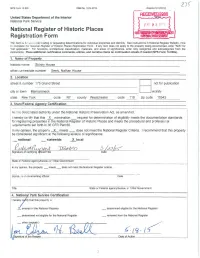

Skinny House Other Names/Site Number S E E~IY~, N a T Ha N H O U S E •______

2J5 NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-001 8 (Expires 5/31/2012) - AEGE\\IED2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Th is form is for use 111 nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin , How to Complete tile Na tional Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable ." For functions , architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Skinny House other names/site number _S_e_e~IY~, _N_a_t_ha_n_H_o_u_s_e_•_________________________ _ 2. Location street & number 175 Grand Street D not for publication city or town _M_a_m_a_ro_n_e_c_k_________________________ LJ vicinity state New York code NY county Westchester code 119 zip code _1_0_5_4_3___ _ 3. State/Federa l Agency Certification I -As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I I hereby certify that this _l__ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional equirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __L meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national , statewide .JLlocal State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government ---------------------- -·--------------- -------- In my opinion, the property _meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

History and Archeology

1. HISTORIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES Historic Overview Earle Shettleworth, Director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, cites Wiscasset as one of three architecturally significant villages in the state, along with the towns of Paris Hill and Castine. Samuel Chamberlain, in his book Towns of New England, chose Wiscasset to represent the State of Maine. He noted that millions were spent restoring Williamsburg, while Wiscasset remains essentially intact. Today, its abundance of classical architecture is evidenced by the inclusion of 10 structures in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) of 1936 and the subsequent inclusion of five buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Buildings. In 1973, a large part of the Village/Historic District became a part of the National Register. In fact, much of the downtown area is a living field museum – and we hold the keys to its future. The first recorded settlement at Wiscasset was in 1660 by George and John Davie. By 1740, there were 30 families at Wiscasset Point, numbering about 150 people. Wiscasset Point was one of three parishes incorporated in Pownalborough in 1760. It took the name of Wiscasset in 1802. As Wiscasset prospered as a deep-harbor shipping port during the late 18th and 19th century, grander homes were built beyond the initial simple, smaller homes closer to the harbor. These include the Nickels-Sortwell House, the Wood-Foote House and the Governor Smith House. Other structures of note are the elegant brick courthouse, which is home to the longest continuously operating courthouse in the country; the Old Jail, in operation until the 1950s; the Wiscasset Library; the Town Common; the Sunken Garden; the Ancient Cemetery, and much more. -

View the Vertical File List

Maryland Historical Trust Library Vertical Files The vertical file collection at the Maryland Historical Trust library contain a wealth of information related to historic buildings and properties from across the state. These files include material which complements reports completed for the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties and National Register of Historic Places, including architectural drawings, newspaper clippings from national, state, and local newspapers, photographs, notes, and ephemera. The vertical files can be viewed in the library, Tuesday through Thursday, by appointment. To schedule an appointment, researchers should contact Lara Westwood, librarian, at [email protected] or 410-697-9546. Please note that this list is incomplete and will be updated. For more information, please contact the librarian or visit the website. Annapolis – Anne Arundel County AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Development Impacts Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Maps Annapolis, Md. AA-2046 Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Annapolis Historic District Annapolis, Md. AA-2046 Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Annapolis Historic District – Research Notes Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Annapolis Emergency Hospital Association Annapolis, Md. AA-360 Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Acton 1 Acton Place, Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Acton Notes Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Acton Place Spring House 11 Acton Place, Annapolis, Md. AA-393 Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Adams-Kilty House 131 Charles Street, Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Alleys Annapolis, Md. AA- Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Annapolis Dock & Market Space Annapolis, Md. AA-1288 Annapolis (Anne Arundel County) Annapolis Elementary School 180 Green Street, Annapolis, Md. -

Freeport, New York

Freeport, New York For other locations with this name, see Freeport (disam- 2.1 Location biguation). Freeport is located at 40°39′14″N 73°35′13″W / 40.65389°N 73.58694°W (40.653935, −73.587005).[4] Freeport (officially The Incorporated Village of Freeport) is a village in the town of Hempstead, Nassau Freeport is bisected by east-west New York State Route County, New York, New York, USA, on the South Shore 27, Sunrise Highway. Meadowbrook Parkway defines its of Long Island. The population was 42,860 at the 2010 eastern boundary. census.[1] A settlement since the 1640s, it was once an oystering community and later a resort popular with the New York City theater community. It is now primarily a 2.2 Surrounding communities bedroom suburb but retains a modest commercial water- front and some light industry. Baldwin lies to the west, Merrick to the east, and Roosevelt to the north. The south village boundary is not precisely defined, lying in the salt flats and bays. 1 Description 3 Government Freeport lies on the south shore of Long Island,[2] in the southwestern part of Nassau County, within the town Freeport’s government is made up of four trustees and a of Hempstead. Freeport has its own municipal electric mayor. One trustee also serves in the capacity of deputy utility, police department, fire, and water departments. mayor. Freeport’s first African American mayor, Andrew Freeport is New York State’s second-biggest village[3] and Hardwick, was elected in 2009, but was succeeded on has a station on the Long Island Rail Road. -

From Vienna to Sarajevo, Role Models and Replicas in the Architecture of Austro-Hungarian Period Boris Trapara

From Vienna to Sarajevo, role models and replicas in the architecture of Austro-Hungarian period Boris Trapara To cite this version: Boris Trapara. From Vienna to Sarajevo, role models and replicas in the architecture of Austro- Hungarian period. Art and art history. Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales- INALCO PARIS - LANGUES O’; International Burch University (Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Department of Architecture), 2019. English. NNT : 2019INAL0023. tel-02992615 HAL Id: tel-02992615 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02992615 Submitted on 6 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales École doctorale n°265 Langues, littératures et sociétés du monde CREE (Centre de Recherche Europes-Eurasie) THÈSE EN COTUTELLE avec Burch Université Internationale Faculté d'Ingénierie et Sciences Naturelles Département d'Architecture présentée par Boris TRAPARA soutenue le 13 décembre 2019 pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l’INALCO en Histoire, sociétés -

Courier Gazette

Issued Tuesday Thursday Thursday Saturday he ourier azette Issue T By Tha C,url«r-G»j«tt... C465 Main St., -G Established January, 1846. Entarad aa Sacond Claat Mall Mattar. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, May 7, 1925 THREE CENTS A COPY Volume 80.................Number 55. CLEAN-UP WEEK AGAIN COMMANDER FULLER EXONERATED The Courier-Gazette THREE-TIMES-A-WEEK KNOX COUNTY ALL THE HOME NEWS When All Citizens Are Expected To Beautify Their Rockland Naval Officer Whose Ship Was Raided For Subscription $3.00 per year payable In ad- Premises—Three Rules To Be Observed. Liquors Receives Complete Vindication. vauce ; single copies three cents Advertising rates based upon circulation and very reasonable. FISH AND GAME ASSOCIATION NEWSPAPER HISTORY Norfolk Va., Mtay 6. (By the Au- qulry which made an investigation t The Rockland Gazette was established In ; sociated Press).—Commander Doug of the case reported that Command 1846. In 1874 the Courier was established THE MAYOR’S SUGGESTIONS las W. Fuller, U. S. N., commanding er Fuller had no knowledge of the and consolidated with the Gazette In 1882. ; the naval transport Beaufort, waft presence of intoxicating liquors on The regular meeting of this Association sched The Free Press was established In 1855, and In 1801 changed Its name to the Tribune. Rubbish is bound to accumulate in and about our homes and un acquitted by a courtmartial at the board. uled for Thursday night has been set over to Thwe papers consolidated March 17, 1897. less it is removed it becomes a menace to health, increases the danger naval base here today of the three Under the naval law holding a of fire, and furthermore gives our premises a cluttered and untidy j charges alleging neglect of duty in commanding officer technically re FRIDAY NIGHT through reasons of necessity. -

ABSTRACT of DISSERTATION Richard Elliott Day the Graduate

ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Richard Elliott Day The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2003 EACH CHILD, EVERY CHILD - FROM EQUITY TO ADEQUACY IN KENTUCKY’S SCHOOLS: THE LEGACY OF THE COUNCIL FOR BETTER EDUCATION ________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the College of Education at the University of Kentucky By Richard Elliott Day Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Susan Scollay, Associate Professor of Administration and Supervision Lexington, Kentucky 2003 Copyright © Richard Elliott Day 2003 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION EACH CHILD, EVERY CHILD - FROM EQUITY TO ADEQUACY IN KENTUCKY’S SCHOOLS: THE LEGACY OF THE COUNCIL FOR BETTER EDUCATION Support for an efficient system of common schools has been a serious problem throughout Kentucky’s history. The General Assembly has long been content to allow Kentucky’s schools to rank among the lowest in the nation. This study attempts to put the current struggle for adequately funded public schools into an historical context, focusing on the Kentucky Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Rose v. Council for Better Education. The study examines this decision in light of present efforts to define and assure a proficient education for each and every child. The activities of the Council for Better Education were part of a national effort to determine a set of judicially manageable standards for equitable and adequate school funding. This study chronicles the activities of the Council for Better Education from its inception in 1984 through 1993 as Kentucky sought to implement a new system of common schools. -

Index to Pioneers of American Landscape History

PIONEERS OF AMERICAN LANDSCAPE DESIGN Index Note: Following the publication of Pioneers of American Landscape Design, LALH editors realized that a com- prehensive index to the book would be a useful resource for readers searching for places, individuals not represented by specific essays, or connective themes. With this in mind, we commissioned an index com- prising more than 2,500 entries, to be available as a downloadable document from our website. This project was initiated with a gift from LALH Trustee Elizabeth Barlow Rogers and completed with generous donations of time and editorial acumen from Mary Bellino. © 2008 by Library of American Landscape History Italicized page numbers refer to in-text illustrations. Boldface numbers refer to color plates and indicate the pages between which the insert falls. Aalto, Alvar, 55 Alaska-Pacific-Yukon Exposition (Seattle, 1909), 77, Abbott, Carlton Sturges, 1 283 Abbott, Stanley William (landscape architect), 1, Albermarle Park (Asheville, N.C.), 480 1–3, 475 Albion College (Albion, Mich.), 478 Blue Ridge Parkway, 1, 2, 54–55, 59–60 Allen, Nellie B. (Osborn) (landscape architect), 3, Acadia National Park (Bar Harbor, Maine), 246–47, 3–6 276, 480 Dellwood (Mount Kisco, N.Y.), 4, 5 Adams, Andrew, 361–62 Persian Garden, 4 (plan) Adams, Brooks and Henry, 117 Alta Vista (Louisville, Ky.), 480 Adams, Charles Gibbs, 247 American Academy in Rome, 303, 447 Addams, Jane, 203, 264 fellows of, 152, 155, 170–71, 260, 308, 357 Adler, David, 262 judges, 120, 135, 149, 417 Admiralty Town House Community (Bay -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 107 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 107 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 147 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JULY 17, 2001 No. 99 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was bluegrass country Monday through Fri- no longer hear Earl Scruggs, ably called to order by the Speaker pro tem- day. At that time the bluegrass pro- backed by Lester Flatt and the Foggy pore (Mr. CULBERSON). gram, as I recall, was aired from noon Mountain Boys as he plays the Flint f until 6 p.m. That time slot subse- Hill Special. During December’s yule- quently was reduced by half running tide season, the Monday through Fri- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO them from 3 until 6 p.m. I did not take day bluegrass fans will be deprived of TEMPORE umbrage with this change and con- Christmas Time A Comin’ by Bill Mon- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- cluded it was not unreasonable. Six roe and the Bluegrass Boys or the fore the House the following commu- hours is, after all, a formidable block Country Gentlemen’s version of Back nication from the Speaker: of time and reducing it to 3 hours ap- Home at Christmas Time. WASHINGTON, DC, peared to be a fair compromise. We, the Monday through Friday July 17, 2001. The recent heavy-handed action group, will have to make adjustments. I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN taken by WAMU is neither fair nor a As a member of Congress, I have con- ABNEY CULBERSON to act as Speaker pro tem- compromise; and as I told a Wash- sistently contributed to WAMU’s var- pore on this day.