NABU-2018-1 FINAL.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nissinen2001.Pdf

THE MELAMMU PROJECT http://www.aakkl.helsinki.fi/melammu/ ÐAkkadian Rituals and Poetry of Divine LoveÑ MARTTI NISSINEN Published in Melammu Symposia 2: R. M. Whiting (ed.), Mythology and Mythologies. Methodological Approaches to Intercultural Influences. Proceedings of the Second Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. Held in Paris, France, October 4-7, 1999 (Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project 2001), pp. 93-136. Publisher: http://www.helsinki.fi/science/saa/ This article was downloaded from the website of the Melammu Project: http://www.aakkl.helsinki.fi/melammu/ The Melammu Project investigates the continuity, transformation and diffusion of Mesopotamian culture throughout the ancient world. A central objective of the project is to create an electronic database collecting the relevant textual, art-historical, archaeological, ethnographic and linguistic evidence, which is available on the website, alongside bibliographies of relevant themes. In addition, the project organizes symposia focusing on different aspects of cultural continuity and evolution in the ancient world. The Digital Library available at the website of the Melammu Project contains articles from the Melammu Symposia volumes, as well as related essays. All downloads at this website are freely available for personal, non-commercial use. Commercial use is strictly prohibited. For inquiries, please contact [email protected]. NISSINEN A KKADIAN R ITUALS AND P OETRY OF D IVINE L OVE MARTTI N ISSINEN Helsinki Akkadian Rituals and Poetry of Divine Love haš adu išakkan u irrub u b it ru ’a mi They perform the ritual of love, they enter the house of love. K 2411 i 19 1. -

Transformation of a Goddess by David Sugimoto

Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 263 David T. Sugimoto (ed.) Transformation of a Goddess Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite Academic Press Fribourg Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Publiziert mit freundlicher Unterstützung der PublicationSchweizerischen subsidized Akademie by theder SwissGeistes- Academy und Sozialwissenschaften of Humanities and Social Sciences InternetGesamtkatalog general aufcatalogue: Internet: Academic Press Fribourg: www.paulusedition.ch Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen: www.v-r.de Camera-readyText und Abbildungen text prepared wurden by vomMarcia Autor Bodenmann (University of Zurich). als formatierte PDF-Daten zur Verfügung gestellt. © 2014 by Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg Switzerland © Vandenhoeck2014 by Academic & Ruprecht Press Fribourg Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen ISBN: 978-3-7278-1748-9 (Academic Press Fribourg) ISBN:ISBN: 978-3-525-54388-7978-3-7278-1749-6 (Vandenhoeck(Academic Press & Ruprecht)Fribourg) ISSN:ISBN: 1015-1850978-3-525-54389-4 (Orb. biblicus (Vandenhoeck orient.) & Ruprecht) ISSN: 1015-1850 (Orb. biblicus orient.) Contents David T. Sugimoto Preface .................................................................................................... VII List of Contributors ................................................................................ X -

Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2005 Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9 Chun Sik Park Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Park, Chun Sik, "Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9" (2005). Dissertations. 121. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/121 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary THEOLOGY OF JUDGMENT IN GENESIS 6-9 A Disseration Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Chun Sik Park July 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3182013 Copyright 2005 by Park, Chun Sik All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Israel & the Assyrians

ISRAEL & THE ASSYRIANS Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, & the Nature of Subversion C. L. Crouch Ancient Near East Monographs – Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Israel and the assyrIans ancient near east Monographs General Editors ehud Ben Zvi roxana Flammini Editorial Board reinhard achenbach esther J. hamori steven W. holloway rené Krüger alan lenzi steven l. McKenzie Martti nissinen Graciela Gestoso singer Juan Manuel tebes Volume Editor Ehud Ben Zvi number 8 Israel and the assyrIans Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, and the Nature of Subversion Israel and the assyrIans Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, and the Nature of Subversion C. l. Crouch sBl Press atlanta Copyright © 2014 by sBl Press all rights reserved. no part of this work may be reproduced or published in print form except with permission from the publisher. Individuals are free to copy, distribute, and transmit the work in whole or in part by electronic means or by means of any informa- tion or retrieval system under the following conditions: (1) they must include with the work notice of ownership of the copyright by the society of Biblical literature; (2) they may not use the work for commercial purposes; and (3) they may not alter, transform, or build upon the work. requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the rights and Permissions Office, sBl Press, 825 houston Mill road, atlanta, Ga 30329, Usa. The ancient near east Monographs/Monografi as sobre el antiguo Cercano Oriente series is published jointly by sBl Press and the Universidad Católica argentina Facultad de Ciencias sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación, Centro de estudios de historia del antiguo Oriente. -

KARUS on the FRONTIERS of the NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo

KARUS ON THE FRONTIERS OF THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo YAMADA * The paper discusses the evidence for the harbors, trading posts, and/or administrative centers called karu in Neo-Assyrian documentary sources, especially those constructed on the frontiers of the Assyrian empire during the ninth to seventh centuries Be. New Assyrian cities on the frontiers were often given names that stress the glory and strength of Assyrian kings and gods. Kar-X, i.e., "Quay of X" (X = a royal/divine name), is one of the main types. Names of this sort, given to cities of administrative significance, were probably chosen to show that the Assyrians were ready to enhance the local economy. An exhaustive examination of the evidence relating to cities named Kar-X and those called karu or bit-kar; on the western frontiers illustrates the advance of Assyrian colonization and trade control, which eventually spread over the entire region of the eastern Mediterranean. The Assyrian kiirus on the frontiers served to secure local trading activities according to agreements between the Assyrian king and local rulers and traders, while representing first and foremost the interest of the former party. The official in charge of the kiiru(s), the rab-kari, appears to have worked as a royal deputy, directly responsible for the revenue of the royal house from two main sources: (1) taxes imposed on merchandise and merchants passing through the trade center(s) under his control, and (2) tribute exacted from countries of vassal status. He thus played a significant role in Assyrian exploitation of economic resources from areas beyond the jurisdiction of the Assyrian provincial government. -

Planets in Ancient Mesopotamia

Enn Kasak, Raul Veede UNDERSTANDING PLANETS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA This is a copy of the article from printed version of electronic journal Folklore Vol. 16 ISSN 1406-0957 Editors Mare Kõiva & Andres Kuperjanov Published by the Folk Belief and Media Group of ELM Electronic Journal of Folklore Electronic version ISSN 1406-0949 is available from http://haldjas.folklore.ee/folklore It’s free but do give us credit when you cite! © Folk Belief and Media Group of ELM, Andres Kuperjanov Tartu 2001 6 UNDERSTANDING PLANETS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Enn Kasak, Raul Veede On our planet time flows evenly everywhere but the history as we know it has different length and depth in every place. Maybe the deepest layer of history lies in the land between Tigris and Eufrat – Mesopotamia (Greek Mesopotam a ‘the land between two rivers’). It is hard to grasp how much our current culture has inherited from the people of that land – be it either the wheel, the art of writing, or the units for measuring time and angles. Science and knowledge of stars has always – though with varying success – been important in European culture. Much from the Babylonian beliefs about con- stellations and planets have reached our days. Planets had an im- portant place in Babylonian astral religion, they were observed as much for calendrical as astrological purposes, and the qualities of the planetary gods were carried on to Greek and Rome. The following started out as an attempt to compose a list of planets together with corresponding gods who lend their names and quali- ties to the planets. -

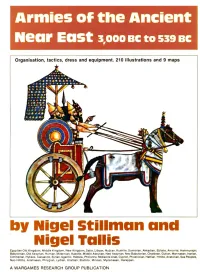

Armies of the Ancient Near E

Armies of the Ancient Near East 3,000 BC to 539 BC Organisation, tactics, dress and equipment. 210 illustrations and 9 maps. by Nigel StiUman and Nigel Tallis Egyptian Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom, S,itc, libyan, Nubian, KU 5hiu~. Sumerian, Akkadian, Eblaitc. Amoritc, HammUl1lpic lhhylonian, Old Assyrian, Human, MilaMian, K.ssitc, Middle: Assyrian, Neo Assyrian, Neo Babylonia n, Chaldun, GUlian, Mannatan, Iranian, Cimmerian, Hyluos. Canaanite, Syrian, Ugaritic, Hebrew, Philistine, Midianitc Arab, Cypriot, Phoenician, Hanian. Hillile, Anatolian, Sea Peoples, Neo Hinile, Aramaun, Phrygian. Lydian. Uranian, Elamilc, Minoan. Mycenaean, Harappan. A WARGAMES RESEARCH GROUP PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION This book. chronologically the finl in the W.R.G. series, attempts the diflkulltaP: ofducribingl he military organisa tion and equipment of the many civilisations ohhe ancienl Near East over a period of 2,500 years. It is du.slening to note tbatthis span oftime is equivalent to half of all recorded history and that a single companion volume, should anyone wish to attempt it, wou.ld have to encompass the period 539 BC to 1922 AD! We hope that our researches will rcOca the: .... St amount of archacologiaJ, pictorial and tarual evidence ..... hich has survived and been rW)vered from this region. It is a matter of some rcp-ct that tbe results of much of the research accumulated in this century has tended to be disperKd among a variety of sometimes obscure publications. Consequently, it is seldom that this mJterial is aplo!ted to its full potcoti.al IS a source for military history. We have attempted 10 be as comptcbensive IS possible and to make UK of the lcuer known sourcCI and the most recent ruearm. -

Isaiah Interwoven

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 15 Number 1 Article 18 1-1-2003 Isaiah Interwoven Kevin L. Barney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Barney, Kevin L. (2003) "Isaiah Interwoven," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 15 : No. 1 , Article 18. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol15/iss1/18 This Biblical Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Isaiah Interwoven Author(s) Kevin L. Barney Reference FARMS Review 15/1 (2003): 353–402. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract Review of Harmonizing Isaiah: Combining Ancient Sources (2001), by Donald W. Parry. I I Kevin L. Barney have had a longstanding interest in biblical languages and lit era- I ture,1 and for that reason I have followed the work of Latter-day Saint Hebraists, such as Donald W. Parry. In his book Harmonizing Isaiah: Combining Ancient Sources, Parry weaves together an English translation of the book of Isaiah drawn from four sources: (1) the Masoretic Text (MT), which is the traditional text of the Hebrew Bible and in general the text underlying the King James Version (KJV) of the Old Testament, (2) the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa) discovered in Cave 1 at Qumran among the Dead Sea Scrolls,2 (3) the Book of Mormon, and (4) the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) of the Bible. -

11 Chapter 1548 15/8/07 10:54 Page 173

11 Chapter 1548 15/8/07 10:54 Page 173 11 Neither Eyewitnesses, Nor Windows to the Past, but Valuable Testimony in its Own Right: Remarks on Iconography, Source Criticism and Ancient Data-processing CHRISTOPH UEHLINGER A single witness shall not suffice to convict a person of any crime or wrong- doing in connection with any offense that may be committed. Only on the evidence of two or three witnesses shall a charge be sustained. If a malicious witness comes forward to accuse someone of wrongdoing, then both parties to the dispute shall appear before the LORD, before the priests and the judges who are in office in those days, and the judges shall make a thorough inquiry. If the witness is a false witness, having testified falsely against another, then you shall do to the false witness just as the false witness had meant to do to the other. So you shall purge the evil from your midst. Deut. 19.15–19 NRSV ITISATOPOS AMONG PRACTITIONERS OF ANCIENT HISTORY to present their work in metaphorical terms as some kind of legal investigation. Historians are trained to balance testimonies of various kinds, which often preserve partial and sometimes conflicting views and interpretations of the past. What are the prerequisites for a fair trial, when we aim at balanced and reasonably accurate historical judgement? To begin with, one might think that we should start to collect as much evidence as possible—a basic principle that sounds like a truism but is not always respected. Moreover, the evidence produced should be of various kinds, which means, for instance, that we should not build a case on verbal testimony alone—essential points may never have been mentioned during the interviews, but ultimately build up a case. -

NABU 2020 2 Compilé 08 NZ

ISSN 0989-5671 2020 N° 2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 38) A Cylinder Seal with a Spread-Wing Eagle and Two Ruminants from Baylor University’s Mayborn Museum — This study shares the (re)discovery of a cylinder seal (AR 12517) housed at Baylor University’s Mayborn Museum Complex.1) The analysis of the seal offers two contributions: First, the study offers a rare record of the business transaction of a cylinder seal by the famous orientalist Edgar J. Banks. Second, the study adds an exceptional and well-preserved example of a cylinder seal engraved with the motif of a spread-wing eagle and two ruminants to the corpus of ancient Near Eastern seals. The study of this motif reveals that the seal published here offers one of the very few examples of a single-register seal which features a spread-wing eagle flanked by a standing caprid and stag. Acquisition History The museum purchased the cylinder seal for $8 from Edgar J. Banks on April 1st, 1937. Various records indicate that Banks traveled to Texas occasionally for speaking engagements and even sold cuneiform tablets to several institutions and individuals in Texas.2) While Banks sold tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets throughout the U.S., this study adds to the comparably modest number of cylinder seals sold by Banks.3) Although Banks’ original letter no longer remains, the acquisition record transcribes Banks’ words as follow: (Seal cylinders) were used for two distinct purposes. First, they were used to roll over the soft clay of the Babylonian contract tablets after they were inscribed, to legalize the contract and to make it impossible to forge or change the contract. -

Righteous Jehu and His Evil Heirs the Deuteronomist’S Negative Perspective on Dynastic Succession

OXFORD THEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS Editorial Committee M. McC. ADAMS M. J. EDWARDS P.M.JOYCE D.N.J.MACCULLOCH O.M.T.O’DONOVAN C.C.ROWLAND OXFORD THEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS RICHARD HOOKER AND REFORMED THEOLOGY A Study of Reason, Will, and Grace Nigel Voak (2003) THE COUNTESS OF HUNTINGDON’S CONNEXION Alan Harding (2003) THE APPROPRIATION OF DIVINE LIFE IN CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA Daniel A. Keating (2004) THE MACARIAN LEGACY The Place of Macarius-Symeon in the Eastern Christian Tradition Marcus Plested (2004) PSALMODY AND PRAYER IN THE WRITINGS OF EVAGRIUS PONTICUS Luke Dysinger, OSB (2004) ORIGEN ON THE SONG OF SONGS AS THE SPIRIT OF SCRIPTURE The Bridegroom’s Perfect Marriage-Song J. Christopher King (2004) AN INTERPRETATION OF HANS URS VON BALTHASAR Eschatology as Communion Nicholas J. Healy (2005) DURANDUS OF ST POURC¸ AIN A Dominican Theologian in the Shadow of Aquinas Isabel Iribarren (2005) THE TROUBLES OF TEMPLELESS JUDAH Jill Middlemas (2005) TIME AND ETERNITY IN MID-THIRTEENTH-CENTURY THOUGHT Rory Fox (2006) THE SPECIFICATION OF HUMAN ACTIONS IN ST THOMAS AQUINAS Joseph Pilsner (2006) THE WORLDVIEW OF PERSONALISM Origins and Early Development Jan Olof Bengtsson (2006) THE EUSEBIANS The Polemic of Athanasius of Alexandria and the Construction of the ‘Arian Controversy’ David M. Gwynn (2006) Righteous Jehu and his Evil Heirs The Deuteronomist’s Negative Perspective on Dynastic Succession DAVID T. LAMB 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective -

Chapter 7 Jerusalem in the Neo-Assyrian Period

Originalveröffentlichung in: Zeidan Kafafi - Robert Schick (Hg.), Jerusalem before Islam. BAR International Series 1699 (2007) S. 40-44 CHAPTER 7 JERUSALEM IN THE NEO-ASSYRIAN PERIOD Wolfgang Rollig It is known but not at all surprising that the city of Der'a. A road did lead eastward to Jericho and into the Jerusalem very seldom comes into view during the period Jordan Valley, but practically no direct access over the of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, i.e., between the rulers Judean Hills toward the west was possible. Therefore, it Assur-dan II and Ashurbanipal and his successors. is not surprising that the state of Judah with its capital Beginning in 935 and continuing until ca. 612 BC, the city Jerusalem lay in the lee of history, remaining Assyrian sources themselves are almost completely silent unharmed by many a historical turbulence. concerning the city. Even in the periods of exceptional Assyrian efforts at westward expansion,1 under However, there were occasional altercations with the Shalmaneser III (859-824) and Tiglath-pileser III (746- Israelite brothers, and Judah frequently meddled in events 727), it is not mentioned, just as the kingdom of Judah, outside its borders, e.g., Asa (908-868) fought against whose capital city had been Jerusalem since the division Baasha of Israel with Damascene support. The northern of the kingdom under Rehoboam, also is rarely men king Ahab, but significantly no Judean, belonged to the tioned in Assyrian sources (see below). There are several coalition of Syrian leaders who setback Shalmaneser Ill's reasons for this silence in the Assyrian sources.