Old Church Slavonic Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Slavic Studies: Concepts, History and Evolution Published Online August 30, 2021

Chin. J. Slavic Stu. 2021; 1(1): 3–15 Wenfei Liu* International Slavic Studies: Concepts, History and Evolution https://doi.org/10.1515/cjss-2021-2003 Published online August 30, 2021 Abstract: This paper departs from the definition of Slavistics and reviews the history of international Slavic studies, from its prehistory to its formal establish- ment as an independent discipline in the mid-18th century, and from the Pan-Slavic movement in the mid-19th century to the confrontation of Slavistics between the East and the West in the mid-20th century during the Cold War. The paper highlights the status quo of international Slavic studies and envisions the future development of Slavic studies in China. Keywords: Slavic studies, Eurasia, International Council for Central and Eastern European Studies (ICCEES), Russian studies (русистика) 1 Definition Slavic studies, or Slavistics (славяноведение or славистика in Russian) refers to the science of studying the societies and cultures of the Slavic countries. The term “Slavic countries” refers normally to the 13 Slavic countries in Eastern and Central Europe, namely Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine in Eastern Slavonia, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia in Western Slavonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Northern Macedonia, Montenegro, Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia of former Yugoslavia. However, some other non-Slavic countries too are often included in Slavic studies, such as Hungary and Romania, countries of former Eastern Bloc, and 12 non-Slavic countries of former Soviet Union—the five Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan), the three Transcaucasian countries (Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia), the three Baltic states (Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia), and Moldova. -

Djerv and Bölzer to Inferno Metal Festival 2020

DJERV AND BÖLZER TO INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2020 We are proud to announce that the Norwegian metal band DJERV and Switzerland's black/death metal duo BÖLZER will perform at Inferno Metal Festival 2020! INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2020: MAYHEM – KAMPFAR – VED BUENS ENDE – CADAVER – MYRKSKOG – BÖLZER – DJERV – SYLVAINE – VALKYRJA DJERV Djerv was formed in 2010 with members from such bands as Animal Alpha, Stonegard and Trelldom. In 2011 they released their self titled debut album to critical acclaim. Their fresh mixture of catchy hard rock and more aggressive metal hit a nerve with their listeners. After only two days in sale the album crashed into the official Norwegian sales charts at an impressive # 8. After some years with heavy touring the band went into hibernation. Now they are back – stronger than ever! After five years the band has returned and will unleash their madness at Inferno Metal Festival 2020! https://www.facebook.com/djervmusic/ BÖLZER Attention came quickly to Switzerland's Bölzer after their 2012 demo “Roman Acupuncture” and subsequent EP “Aura” in 2013 due to their ability to create fascinating black metal melodies and dissonant structures with only two members in the band. Their debut album “Hero” was released in 2016 and was incredibly well received and as such the duo have been invited to play all over the world. Now it is time to finally play at Inferno Metal Festival! https://www.facebook.com/erosatarms/ INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2020 Inferno Metal Festival 2020 marks the 20 years anniversary of the festival. This makes the festival the longest running metal festival in Norway and one of the most important extreme metal festivals in the world. -

Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Ústav Archeologie a Muzeologie

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV ARCHEOLOGIE A MUZEOLOGIE Teória včasnostredovekých depotov z prostredia západných a južných Slovanov Dizertačná práca Autorka: Mgr. Mária Müllerová Školiteľ: prof. Mgr. Jiří Macháček, Ph.D. Brno 2020 Prehlasujem, že som dizertačnú prácu vypracovala samostatne s využitím uvedených prameňov a literatúry. ............................ Mária Müllerová Poďakovanie Na prvom mieste by som chcela poďakovať prof. Macháčkovi, za jeho neoceniteľnú pomoc a trpezlivosť počas tvorby dizertačnej práce. Ďakujem mu za jeho podnetné pripomienky, ako urobiť prácu ešte lepšou a podporu najmä v čase, keď už som sa sama chcela vzdať. Vzhľadom k tomu, že ide o geograficky široký záber rada by som na tomto mieste poďakovala jednotlivo odborníkom, ktorí mi pomohli alebo ma usmernili v hľadaní depotov, resp. zdrojov k problematike včasného stredoveku v jednotlivých oblastiach. Z Nemecka ide najmä o F. Bierrmann-a, z Rakúska E. Nowotny a S. Eichert. Z Maďarska mi pomohli B. M. Szöke, S. Merva, M. Harag a A. Csuthy. Rada by som poďakovala za pomoc orientovať sa v téme včasného stredoveku južných Slovanov srbskej archeologičke M. Radišič a z Bulharska S. Doncheva. Za pomoc v súvislosti so sekerovitými hrivnami ďakujem M. Hlavicovi. V neposlednom rade by som chcela poďakovať za pomoc a podporu mojím kolegom a priateľom zo spoločnosti ProArch Prospektion und Archäologie GmbH Ingolstadt: A. Šteger, S. Morvayová, V. Planert, D. Biedermann, R. Münds-Lugauer, P. Spišák, A. Heckendorff, T. Riegg, M. Flämig, B. Ernst a v neposlednom rade ďakujem mojej šéfke K. Lenk-Aguerrebere, ktorá ma s láskavým pochopením uvoľnila na istú dobu z práce, aby som mohla v pokoji a v kľude, dokončiť svoju dizertačnú prácu. -

Peace Corps Romania Survival Romanian Language Lessons Pre-Departure On-Line Training

US Peace Corps in Romania Survival Romanian Peace Corps Romania Survival Romanian Language Lessons Pre-Departure On-Line Training Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………… 2 Lesson 1: The Romanian Alphabet………………………………………………… 3 Lesson 2: Greetings…………………………………………………………………… 4 Lesson 3: Introducing self…………………………………………………………… 5 Lesson 4: Days of the Week…………………………………………………………. 6 Lesson 5: Small numbers……………………………………………………………. 7 Lesson 6: Big numbers………………………………………………………………. 8 Lesson 7: Shopping………………………………………………………………….. 9 Lesson 8: At the restaurant………………………………………………………..... 10 Lesson 9: Orientation………………………………………………………………… 11 Lesson 10: Useful phrases ……………………………………………………. 12 1 Survival Romanian, Peace Corps/Romania – December 2006 US Peace Corps in Romania Survival Romanian Introduction Romanian (limba română 'limba ro'mɨnə/) is one of the Romance languages that belong to the Indo-European family of languages that descend from Latin along with French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. It is the fifth of the Romance languages in terms of number of speakers. It is spoken as a first language by somewhere around 24 to 26 million people, and enjoys official status in Romania, Moldova and the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (Serbia). The official form of the Moldovan language in the Republic of Moldova is identical to the official form of Romanian save for a minor rule in spelling. Romanian is also an official or administrative language in various communities and organisations (such as the Latin Union and the European Union – the latter as of 2007). It is a melodious language that has basically the same sounds as English with a few exceptions. These entered the language because of the slavic influence and of many borrowing made from the neighboring languages. It uses the Latin alphabet which makes it easy to spell and read. -

+1. Introduction 2. Cyrillic Letter Rumanian Yn

MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM +1. INTRODUCTION These are comments to "Additional Cyrillic Characters In Unicode: A Preliminary Proposal". I'm examining each section of that document, as well as adding some extra notes (marked "+" in titles). Below I use standard Russian Cyrillic characters; please be sure that you have appropriate fonts installed. If everything is OK, the following two lines must look similarly (encoding CP-1251): (sample Cyrillic letters) АабВЕеЗКкМНОопРрСсТуХхЧЬ (Latin letters and digits) Aa6BEe3KkMHOonPpCcTyXx4b 2. CYRILLIC LETTER RUMANIAN YN In the late Cyrillic semi-uncial Rumanian/Moldavian editions, the shape of YN was very similar to inverted PSI, see the following sample from the Ноул Тестамент (New Testament) of 1818, Neamt/Нямец, folio 542 v.: file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 1 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM Here you can see YN and PSI in both upper- and lowercase forms. Note that the upper part of YN is not a sharp arrowhead, but something horizontally cut even with kind of serif (in the uppercase form). Thus, the shape of the letter in modern-style fonts (like Times or Arial) may look somewhat similar to Cyrillic "Л"/"л" with the central vertical stem looking like in lowercase "ф" drawn from the middle of upper horizontal line downwards, with regular serif at the bottom (horizontal, not slanted): Compare also with the proposed shape of PSI (Section 36). 3. CYRILLIC LETTER IOTIFIED A file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 2 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM I support the idea that "IA" must be separated from "Я". -

Literacy and Census: E Case of Banat Bulgarians, 1890–1910

144 P P Literacy and Census: e Case of Banat Bulgarians, 1890–1910 Literacy is a dynamic category that changes over time. e understanding of writing has gradually been expanding while its public signi cance has been increasing. e transition to widespread literacy was performed from the 17 th to the 19 th centuries and was connected with the rise of the bourgeoisie, with the development of services and technology that generated economic demand for literate workers. is transition was a slow and gradual process and deve- loped at di erent rates in di erent geographical regions, but from a global point of view it was marked by unprecedented social transformation: while in the mid-19 th century only 10% of the adult population of the world could read and write, in the 21 st century – despite the ve-fold increase in population – 80% have basic literacy. 1 In recent decades this transformation has caused a considerable research interest in the history of literacy and the process of over- coming illiteracy. On the Subject of Research Herein, with respect to the spread of literacy in Austria–Hungary are studied the Banat Bulgarians, who are Western Rite Catholics. In 1890 they numbered 14 801 people. At that time the Banat Bulgarians had already been seled in the Habsburg Empire for a century and a half. ey were refugees from the district of Chiprovtsi town (Northwestern Bulgaria) who had le Bulgarian lands aer the unsuccessful anti-Ooman uprising of 1688. Passing through Wallachia and Southwest Transylvania (the laer under Austrian rule) in the 1 Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006. -

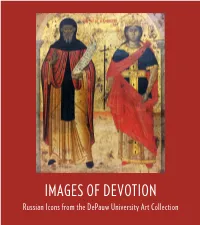

Images of Devotion

IMAGES OF DEVOTION Russian Icons from the DePauw University Art Collection INTRODUCTION Initially conceived in the first century, religious icons have a long history throughout the Christian world.1 The icon was not simply created to mirror the physical appearance of a biblical figure, but to idealize him or her, both physically and spiritually.2 Unlike Western Christianity where religious art can be appreciated solely for its beauty and skill alone, in the Orthodox tradition, the icon becomes more than just a reflection – it is a vehicle for the divine essence contained within.3 Due to the sacred nature of the icon, depictions of biblical figures became not only desirable in the Orthodox tradition, but an absolute necessity. Religious icons were introduced to Russia during the official Christianization of the country under Vladimir, the Great Prince of Kiev, in 988. After this period, many regional schools developed their own indigenous styles of icon painting, such as: Pokov, Novgorod, Moscow, Suzdal, and Jaroslavl.4 Upon Moscow’s emergence as Christ with Twelve Apostles the religious and political capital of Russia in the Russian Artist, Date Unknown Tempura Paint on Panel sixteenth century, it cemented its reputation as DePauw Art Collection: 1976.31.1 the great center for icon painting. Gift of Earl Bowman Marlatt, Class of 1912 The benefactor of this collection of Russian This painting, Christ with Twelve Apostles, portrays Jesus Christ iconography, Earl Bowman Marlatt (1892-1976), reading a passage from the Gospel of Matthew to his Apostles.7 was a member of the DePauw University class Written in Old Church Slavonic, which is generally reserved of 1912. -

The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 223 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) George Thomas The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 S lavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 223 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 GEORGE THOMAS THE IMPACT OF THEJLLYRIAN MOVEMENT ON THE CROATIAN LEXICON VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1988 George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access ( B*y«ftecne I Staatsbibliothek l Mönchen ISBN 3-87690-392-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1988 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, GeorgeMünchen Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 FOR MARGARET George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access .11 ж ־ י* rs*!! № ri. ur George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 Preface My original intention was to write a book on caiques in Serbo-Croatian. -

RUSSIAN ATHEMATIC VERBS, WITHOUT STRESS (AND WITH) Atelier De Phonologie, SFL, March 20, 2019

Ora Matushansky, SFL (CNRS/Université Paris-8/SFL)/UiL OTS/Utrecht University email: Ora.Mаtushа[email protected] homepage: http://www.trees-and-lambdas.info/matushansky/ RUSSIAN ATHEMATIC VERBS, WITHOUT STRESS (AND WITH) Atelier de phonologie, SFL, March 20, 2019 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The structure of the Russian verb Borrowing from prior work by Halle 1963, Lightner 1967, self, and Tatevosov: (1) a. [[[[[[PFX + stem] + v] + ASP] + THEME] + TENSE] + AGR] finite forms b. [[[[[[[PFX + stem] + v] + ASP] + THEME] + TENSE] + PRT] + AGR] participial forms c. [[[[[[PFX + stem] + v] + ASP] + THEME] + TENSE] + GER] gerund forms d. [[[[[[PFX + stem] + v] + ASP] + THEME] + TENSE] + IMP] imperative e. [[[[[PFX + stem] + v] + ASP] + THEME] + INF] infinitive Illustration: (2) [[[za-PFX + [[[bol- pain + e-v] + v-IMPV] + aj-THEME]] + e-PRES] + m-1PL] ‘we are getting sick’ To be disregarded here: Prefixes: can be iterated, unaccented with the exception of the accented vy- ‘out’ Aspectual suffixes: the secondary imperfective -yv-/-v-/-Ø- and the semelfactive -nu- (both accented, but see Matushansky 2009 on the former) Themes: all accented, subject for future work Verbalizing suffixes: -e-, -ov-, etc. Reason: the fewer pieces, the easier it is to determine what happens with inflection 1.2. Russian yers Slavic is famous for its abstract vowels (Halle 1959, Lightner 1972, Pesetsky 1979, Halle and Vergnaud 1987, etc.): (3) a. túrk-a ‘Turk.GEN’ túrok ‘Turk.NOM’ back yer b. osl-á ‘donkey.GEN’ os'ól ‘donkey.NOM’ front yer (4) a. párk-a ‘park-SG.GEN’ párk ‘park-SG.NOM’ b. rósl-a ‘stalwart.F.SG’ rósl ‘stalwart.M.SG’ Russian has two: the front one ([ĭ]) and the back one ([ŭ], some people think: [ĭ]) Their vocalization is mostly governed by the yer-lowering rule (cf. -

Michael Biggins Cv Highlights

MICHAEL BIGGINS CV HIGHLIGHTS 5405 NE 74th Street Telephone: (206) 543-5588 Seattle, WA 98115 USA E-mail: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Affiliate Professor, Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Washington, 2000 - present. Teach courses in Slovenian language (all levels), advanced Russian language, Slavic to English literary translation, Slovenian literature. Head, International Studies Units, University of Washington Libraries, 2004-present. Oversight and coordination of staff and activities of Near East Section, Slavic and East European Section, Southeast Asia Section, and materials processing for South Asia. Head, Slavic and East European Section, University of Washington Libraries, 1994 - present (tenured, 1997). Librarian for Slavic, Baltic and East European studies. Interim Librarian for Scandinavian Studies, 2011- 2012. Coordinator for International Studies units (Near East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Slavic), 1997-1999, 2004-present. Fund group manager, International Studies (Slavic, East Asia, Near East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Latin America and others), 2010-present. Slavic Catalog Librarian and South Slavic Bibliographer, University of Kansas Libraries, 1988-1994 (tenured, 1993). Assistant Professor of Russian, Knox College, Galesburg, Ill., 1986-1987. Instructor of Russian, Middlebury College Russian Summer School, Middlebury, Vt., 1986-87. Assistant Professor of Russian, St. Michael's College, Colchester, Vt., 1985-1986. Russian Language Summer Study Abroad Instructor/Group Leader, University of Kansas, led groups of 20-25 U.S. students enrolled in summer intensive Russian language program in Leningrad, Soviet Union, 1981 and 1982. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND PhD, Honors, Slavic Languages and Literatures: University of Kansas (1985). MS, Library and Information Science: University of Illinois/Champaign-Urbana (1988). MA, Honors, Germanic Languages and Literatures: University of Kansas (1978). -

Download Download

Journal of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music Vol. 4 (1), Section II: Conference papers, pp. 83-97 ISSN 2342-1258 https://journal.fi/jisocm Stifling Creativity: Problems Born out of the Promulgation of the 1906 Tserkovnoje Prostopinije Fr Silouan Sloan Rolando [email protected] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Greek Catholic Bishop of the city of Mukačevo in what is now Ukraine promulgated an anthology of Carpatho- Rusyn chant known as the Церковноє Простопѣніє (hereafter, the Prostopinije) or Ecclesiastical Plainchant. While this book follows in the tradition of printed Heirmologia found throughout the Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches of Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia starting in the sixteenth century, this book presents us with a number of issues that affect the quality and usability of this chant in both its homeland and abroad as well as in the original language, Old Church Slavonic, and in modern languages such as Ukrainian, Hungarian and English. Assuming that creativity is more than just producing new music out of thin air, the problems revealed in the Prostopinije can be a starting point the better to understand how creativity can be unintentionally stifled and what can be done to overcome these particular obstacles. A Brief History Heirmologia in this tradition are anthologies of traditional chant that developed in the emergence of the Kievan five-line notation in place of the older Znamenny neums. With the emergence of patterned chant systems variously called Kievan, Galician, Greek and Bulharski, each touting unique melodies for each tone and each element of liturgy, the Heirmologia would be augmented with these chants often replacing the older Znamenny, especially for the troparia, stichera and prokeimena of the Octoechos. -

St. John the Baptist Catholic Church St. Mary Catholic Church St. Martin

St. Mary St. John the Baptist Catholic Church Catholic Church 815 St. Mary’s Church Rd. 207 E. Bell St. Fayetteville (near Ellinger) Fayetteville www.stmaryellinger.com www.stjohnfayetteville.com Pope Francis Bishop Joe S. Vásquez Vatican City State Diocese of Austin MASSES Tuesday at 6:00 p.m. For the souls of Leo & Josephine Noska Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. For the soul of Rudy Jurecka MASSES Thursday at 7:00 a.m. For the soul of Dorothy Krenek Wednesday at 7:00 a.m. Friday at 6:00 p.m. St. Martin For the souls of For the soul of Rhonda Canik John, Albina, James & Larry Urban Saturday at 7:30 a.m. Catholic Church Thursday at 6:00 p.m. For the soul of Louis John Mascheck, Jr. World’s Smallest Catholic Church For the soul of Susan Petter Saturday Vigil at 6:00 p.m. 3490 S. Hwy 237 Friday at 7:00 a.m. Round Top For the souls of For the soul of Laddie Vasek (near Warrenton) Mary & Robert Kasmiersky, Sr. Sunday at 8:00 a.m. For the soul of Garland C. Polasek Sunday at 10:00 a.m. MONTHLY MASS For the People Tuesday, September 12, at 9:00 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation Sacrament of Reconciliation For the intentions left on the altar Before every Mass Saturday 4:30-5:30 p.m. Wednesday 6:00-6:30 p.m. First Friday 4:00-5:30 p.m. Mailing Address and Contact Information for all three Churches Rev. Nock Russell, Pastor P.O.