When You Have Not Decided Where to Go, No Wind Can Take You There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hezbollah-Israeli

The Hizbullah-Israeli War: an American Perspective Aaron David Miller It was unusual for an Israeli Prime Minster to break open a bottle of champagne in front of American negotiators at a formal meeting. But that’s exactly what Shimon Peres did. It was late April 1996, and Peres was marking the end of a bloody three week border confrontation with Hizbullah diffused only by an intense ten day shuttle orchestrated by Secretary of State Warren Christopher. Those understandings negotiated between the governments of Israel and Syria (the latter standing in for Hizbullah) would create an Israeli-Lebanese monitoring group, co-chaired by the United States and France. These arrangements were far from perfect, but contributed, along with on-again-off-again Israeli-Syrian negotiations, to an extended period of relative calm along the Israeli- Lebanese border. The April understandings would last until Israel’s withdrawal. The recent summer war between Hizbullah and Israel, triggered by the Shia militia’s attack on an Israeli patrol on July 12, masked a number of other factors which would set the stage for the confrontation as well as the Bush administration’s response. Six years of relative quiet had witnessed Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon in June of 2000, a steady supply of Katushya rockets—both short and long range—from Iran to Hizbullah, the collapse of Israel’s negotiations with Syria and the Palestinians, and the onset of the worst Israeli-Palestinian war in half a century. A perfect storm was brewing, spawned by the empowerment of both Hizbullah and Hamas, Iranian reach into the Arab-Israeli zone, Syria’s forced withdrawal from Lebanon, a determination by Israel to restore its strategic deterrence in the wake of unilateral withdrawals from Lebanon and Gaza, and an inexperienced Israeli prime minister and defense minister uncertain of how that should be done. -

New Report ID

Number 21 April 2004 BAKER INSTITUTE REPORT NOTES FROM THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY BAKER INSTITUTE CELEBRATES ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY Vice President Dick Cheney was man you only encounter a few the keynote speaker at the Baker times in life—what I call a ‘hun- See our special Institute’s 10th anniversary gala, dred-percenter’—a person of which drew nearly 800 guests to ability, judgment, and absolute gala feature with color a black-tie dinner October 17, integrity,” Cheney said in refer- 2003, that raised more than ence to Baker. photos on page 20. $3.2 million for the institute’s “This is a man who was chief programs. Cynthia Allshouse and of staff on day one of the Reagan Rice trustee J. D. Bucky Allshouse years and chief of staff 12 years ing a period of truly momentous co-chaired the anniversary cel- later on the last day of former change,” Cheney added, citing ebration. President Bush’s administra- the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cheney paid tribute to the tion,” Cheney said. “In between, Persian Gulf War, and a crisis in institute’s honorary chair, James he led the treasury department, Panama during Baker’s years at A. Baker, III, and then discussed oversaw two landslide victories in the Department of State. the war on terrorism. presidential politics, and served “There is a certain kind of as the 61st secretary of state dur- continued on page 24 NIGERIAN PRESIDENT REFLECTS ON CHALLENGES FACING HIS NATION President Olusegun Obasanjo of the Republic of Nigeria observed that Africa, as a whole, has been “unstable for too long” during a November 5, 2003, presentation at the Baker Institute. -

Hamas in Power

PALESTINIANS, ISRAEL, AND THE QUARTET: PULLING BACK FROM THE BRINK Middle East Report N°54 – 13 June 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE INTER-PALESTINIAN STRUGGLE ............................................................... 2 A. HAMAS IN GOVERNMENT ......................................................................................................3 B. FATAH IN OPPOSITION...........................................................................................................9 C. A MARCH OF FOLLY? .........................................................................................................13 D. THE PRISONERS’S INITIATIVE AND REFERENDUM................................................................16 III. THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY AND THE PALESTINIAN CRISIS.. 21 A. PA BUDGETARY COSTS, DONOR CONTRIBUTIONS AND DONOR ATTITUDES ..........................21 B. A NATION UNDER SIEGE .....................................................................................................26 C. CAN A HUMANITARIAN COLLAPSE BE AVOIDED WITHOUT DEALING WITH THE PA? ........27 IV. CONCLUSION: WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? ....................................................... 32 A. SUBVERTING HAMAS? ........................................................................................................32 B. STRENGTHENING ABBAS? ...................................................................................................34 -

Israel and the Palestinians After the Arab Spring: No Time for Peace

Istituto Affari Internazionali IAI WORKING PAPERS 12 | 16 – May 2012 Israel and the Palestinians After the Arab Spring: No Time for Peace Andrea Dessì Abstract While spared from internal turmoil, Israel and the Palestinian Territories have nonetheless been affected by the region’s political transformation brought about by the Arab Spring. Reflecting what can be described as Israel’s “bunker” mentality, the Israeli government has characterized the Arab revolutionary wave as a security challenge, notably given its concern about the rise of Islamist forces. Prime Minister Netanyahu has capitalized on this sense of insecurity to justify his government’s lack of significant action when it comes to the peace process. On the Palestinian side, both Hamas and Fatah have lost long-standing regional backers in Egypt and Syria and have had to contend with their increasingly shaky popular legitimacy. This has spurred renewed efforts for reconciliation, which however have so far produced no significant results. Against this backdrop, the chances for a resumption of serious Israeli-Palestinian peace talks appear increasingly dim. An effort by the international community is needed to break the current deadlock and establish an atmosphere more conducive for talks. In this context, the EU carries special responsibility as the only external actor that still enjoys some credibility as a balanced mediator between the sides. Keywords : Israel / Israeli foreign policy / Arab revolts / Egypt / Muslim Brotherhood / Palestine / Gaza / Hamas / Fatah / Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations / European Union © 2012 IAI IAI Working Papers 1216 Israel and the Palestinians After the Arab Spring: No Time for Peace Israel and the Palestinians After the Arab Spring: No Time for Peace by Andrea Dessì ∗ Introduction The outbreak of popular protests throughout the Middle East and North Africa in early 2011 came as a shock to the world. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Cabinet Resolution Regarding the Disengagement Plan

The Cabinet Resolution Regarding the Disengagement Plan 6 June 2004 Addendum A - Revised Disengagement Plan - Main Principles Addendum C - Format of the Preparatory Work for the Revised Disengagement Plan Addendum A - Revised Disengagement Plan - Main Principles 1. Background - Political and Security Implications The State of Israel is committed to the peace process and aspires to reach an agreed resolution of the conflict based upon the vision of US President George Bush. The State of Israel believes that it must act to improve the current situation. The State of Israel has come to the conclusion that there is currently no reliable Palestinian partner with which it can make progress in a two-sided peace process. Accordingly, it has developed a plan of revised disengagement (hereinafter - the plan), based on the following considerations: One. The stalemate dictated by the current situation is harmful. In order to break out of this stalemate, the State of Israel is required to initiate moves not dependent on Palestinian cooperation. Two. The purpose of the plan is to lead to a better security, political, economic and demographic situation. Three. In any future permanent status arrangement, there will be no Israeli towns and villages in the Gaza Strip. On the other hand, it is clear that in the West Bank, there are areas which will be part of the State of Israel, including major Israeli population centers, cities, towns and villages, security areas and other places of special interest to Israel. Four. The State of Israel supports the efforts of the United States, operating alongside the international community, to promote the reform process, the construction of institutions and the improvement of the economy and welfare of the Palestinian residents, in order that a new Palestinian leadership will emerge and prove itself capable of fulfilling its commitments under the Roadmap. -

6086 AR Cover R1:17.310 MFAH AR 2015-16 Cover.Rd4.Qxd

μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2015–2016 MFAH BY THE NUMBERS July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 • 900,595 visits to the Museum, the Lillie and Hugh Roy Tuition Attendance Revenue $3.2 Other Cullen Sculpture Garden, Bayou Bend Collection and $2.1 5% 3% $7.1 Gardens, Rienzi, and the Glassell School of Art 11% Membership Revenue $2.9 • 112,000 visitors and students reached through learning 5% and interpretation programs on-site and off-site FY 2016 • 37,521 youth visitors ages 18 and under received free Operating Operating Revenues Endowment or discounted access to the MFAH Fund-raising (million) Spending $14.2 $34.0 22% 54% • 42,865 schoolchildren and their chaperones received free tours of the MFAH • 1,020 community engagement programs were presented Total Revenues: $63.5 million • 100 community partners citywide collaborated with the MFAH Exhibitions, Curatorial, and Collections $12.5 Auxiliary • 2,282,725 visits recorded at mfah.org 20% Activities $3.2 5% • 119,465 visits recorded at the new online collections Fund-raising $4.9 module 8% • 197,985 people followed the MFAH on Facebook, FY 2016 Education, Instagram, and Twitter Operating Expenses Libraries, (million) and Visitor Engagment $12.7 • 266,580 unique visitors accessed the Documents 21% of 20th-Century Latin American and Latino Art Website, icaadocs.mfah.org Management Buildings and Grounds and General $13.1 and Security $15.6 21% • 69,373 visitors attended Sculpted in Steel: Art Deco 25% Automobiles and Motorcycles, 1929–1940 Total Expenses: $62 million • 26,434 member -

Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North the Role of the Arab States Africa Programme

Briefing Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North The Role of the Arab States Africa Programme Yossi Mekelberg Summary and Greg Shapland • The positions of several Arab states towards Israel have evolved greatly in the past 50 years. Four of these states in particular – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and (to a lesser extent) Jordan – could be influential in shaping the course of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. • In addition to Egypt and Jordan (which have signed peace treaties with Israel), Saudi Arabia and the UAE, among other Gulf states, now have extensive – albeit discreet – dealings with Israel. • This evolution has created a new situation in the region, with these Arab states now having considerable potential influence over the Israelis and Palestinians. It also has implications for US positions and policy. So far, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and Jordan have chosen not to test what this influence could achieve. • One reason for the inactivity to date may be disenchantment with the Palestinians and their cause, including the inability of Palestinian leaders to unite to promote it. However, ignoring Palestinian concerns will not bring about a resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, which will continue to add to instability in the region. If Arab leaders see regional stability as being in their countries’ interests, they should be trying to shape any eventual peace plan advanced by the administration of US President Donald Trump in such a way that it forms a framework for negotiations that both Israeli and Palestinian leaderships can accept. Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking: The Role of the Arab States Introduction This briefing forms part of the Chatham House project, ‘Israel–Palestine: Beyond the Stalemate’. -

78% of Construction Was in “Isolated Settlements”*

Peace Now’s Annual Settlement Construction Report for 2017 Construction Starts in Settlements were 17% Above Average in 2017 78% of Construction was in “Isolated Settlements”* Settlement Watch, Peace Now Key findings – Construction in the West Bank, 2017 (East Jerusalem excluded) 1 According to Peace Now's count, 2,783 new housing units began construction in 2017, around 17% higher than the yearly average rate since 2009.2 78% (2,168 housing units) of the new construction was in settlements east of the proposed Geneva Initiative border, i.e. settlements that are likely to be evicted in a two-state agreement. 36% (997 housing units) of the new construction was in areas that are east of the route of the separation barrier. Another 46% (1,290 units) was between the built and the planned route of the fence. Only 18% was west of the built fence. At least 10% (282 housing units) of the construction was illegal according to the Israeli laws applied in the Occupied Territories (regardless of the illegality of all settlements according to the international law). Out of those, 234 units (8% of the total construction) were in illegal outposts. The vast majority of the new construction, 91% (2,544 housing units), was for permanent structures, while that the remainder 9% were new housing units in the shape of mobile homes both in outposts and in settlements. 68 new public buildings (such as schools, synagogues etc.) started to be built, alongside 69 structures for industry or agriculture. Advancement of Plans and Tenders (January-December 2017) 6,742 housing units were advanced through promotions of plans for settlements, in 59 different settlements (compared to 2,657 units in 2016). -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Avoiding Last Period Defection Within Israeli-Palestinian Final

Breaking the Stalemate: Avoiding Last Period Defection within Israeli-Palestinian Final Status Negotiations through Statistical Modeling John J. Villa Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a B.A. with Honors From the Political Science Department at Duke University March 31, 2017 1 Forward: --First, I must thank the phenomenal Political Science Department at Duke University and my thesis advisor Dr. Michael C. Munger for their tremendous support while I developed my thesis and during my general education. Dr. Munger’s leadership, creativity, and generosity provided the foundation upon which I write to you, and his impact upon this publication was critical. --To Dr. Abdeslam E. M. Maghraoui, thank you for instructing me in three tremendous Middle East Studies courses and helping me establish the foundational aspects of this publication. Your mentorship and sharing of knowledge provided an entry point into subject matter far beyond anything I ever thought I would reach. -- To Dr. Mbaye Lo, thank you for your unwavering support, challenging materials, and educated discussions. Our long debates in your office are some of my fondest memories of my time in Durham. --To the staff of the Data Visualization Lab staff at Duke University consisting of Mark Thomas, Angela Zoss, John Little, and Jena Happ, your expertise, patience, and assistance in ArcGIS, Open Refine, and general data manipulation were extremely helpful during the computational portion of this publication and for that I thank you. --To Ryan Denniston, your assistance in Microsoft Excel functions and ArcGIS modeling was impeccable. This is, of course, in addition to your generosity, patience, and creatively which I’m sure were tested day after day coding together in the lab as you guided me through the ever-more complex ArcGIS models. -

Shelter 2014 A3 V1 Majed.Pdf (English)

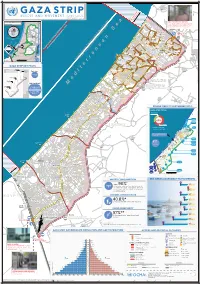

GAZA STRIP: Geographic distribution of shelters 21 July 2014 ¥ 3km buffer Zikim a 162km2 (44% of GaKazrmaiya area) 100,000 poeple internally displaced e Estimated pop. of 300,000 B?4 84,000 taking shelter in UNRWA schools S Yad Mordekhai n F As-Siafa B?4 B?34 Governorate # of IDPs a ID y d e e e h b s a R Netiv ha-Asara Gaza 3 2,401 l- n d A e a c Erez Crossing KhanYunis 9 ,900 r Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) r (Umm An-Naser) fo 4 º» r h ¹ a n 1 al n Middle 7 ,200 S ee 0 l-D e E 2 E t Beit Lahiya 'Izbat Beit Hanoun a t i k k y E a e l- j S North 2 1,986 l B lo l- i a a A m h F a - 34 i u r l B? J A 5! 5! 5! d L t 'Arab Maslakh Madinat al 'Awda i S w Rafah 1 2,717 ta 5! Beit Lahiya r af 5! ! ee g 5! S 5 az Ash Shati' Camp l- 5! W Beit Hanoun e A !5! Al- n 5!5! 5 lil 5!5! Al-q ka ha i uds ek K 5! l-S Grand Total 8 4,204 M h 5!Jabalia A s 5!5! Jabalia Camp i 5!5! D S !x 5!5!5! a a r le a d h Source of data: UNRWA F o m n a 5!5! a r a K J l- a E m l a a l A n b 5! a 5!de Q 5! l l- d N A Gaza e as e e h r s City a R l- A 5!5! 5! 5! s d ! Mefalsim u 5! Q ! 5! l- 5 A 5! A l- M o n a t 232 kk a B? e r l-S A Kfar Aza d a o R l ta s a o C Sa'ad Al Mughraqa arim Nitz ni - (Abu Middein) Kar ka ek n ú S ú 5! e b l- B a A r tt Juhor ad Dik a a m h K O l- ú A ú Alumim An Nuseirat Shuva Camp 5! 5! Zimrat B?25 5! 5! 5! I S R A E L n e e 5! Kfar Maimon D a 5! - k Tushiya l k Al Bureij Camp E e Az Zawayda h S la l- a A S 5! Be'eri !x 5! Deir al Balah Al Maghazi Shokeda Camp 5! 5! Deir al Balah 5!5! Camp Al Musaddar d a o f R la k l a o ta h o 232