Light's Golden Jubilee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 4 (1929-1930)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Bowdoin Alumni Magazines Special Collections and Archives 1-1-1930 Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 4 (1929-1930) Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines Recommended Citation Bowdoin College, "Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 4 (1929-1930)" (1930). Bowdoin Alumni Magazines. 4. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowdoin Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BOWDOIN ALUMNUS Member of the American Alumni Council Published by Bowdoin Publishing Company, Brunswick, Maine, four times during the College year Subscription price, $1.50 a year. Single copies, 40 cents. With Bowdoin Orient, $3.50 a year. Entered as second-class matter, Nov. 21st, 1927, at the Postoffice at Brunswick, Maine, under the Act of March 3, 1879. Philip S. Wilder '23, Editor O. Sewall Pkttingill, Jr., '30, Undergraduate Editor Ralph B. Hirtle '30, Business Manager ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD Arthur G. Staples '82 William H. Greeley '90 Dwight H. Sayward 'i6 Albert W. Tolman '88 Alfred E. Gray '14 Bela W. Norton '18 William M. Emery '89 Austin H. MacCormick '15 Walter F. Whittier '27 Contents for November 1929 Vol. IV Xo. i PAGE Bowdoin—An Appraisal—James L. McConaughy, A.M., 'n i Bowdoin's 124TH Commencement—John W. Frost '04 3 Several New Men on Faculty 5 The Alumni Council Athletic Report . -

Edison History General

■■■bX'--i Idtekn Twp. Pub-1 34<yPlainiield AvO gdtaon, N. J. O te n NOT. TO BE TAKEN FROM UBBAHT SAM O'AMICO/The News Tribune Andy Hoffman waiting for a ride near the Blueberry Manor Apartments off Plainfield Avenue in Edison’s Stelton section. Stelton a ‘bit of everything’ Edison section has tree-lined streets, strip malls, condos By ANTHONY A. GALLOnO News Tribune Staff Writer EDISON “Mixed nuts” is how William Burnstile describes the town’s Stelton section. “It’s a little bit of everything, but it’s nice to come home to,” says the 58-year- old New York native who moveid to Stelton in 1987. Burnstile quibbles over the word “neighborhood.” “It’s not a neighbor hood in the New York sense of the word. Like I said, there’s a bit of every thing.” The older Stelton section sits north of Route 27 on a series of tree-line streets that branch off Plainfield Road. The Edison train station, off Central Ave nue, divides that community from a JEFFERY COHEOTIw Nww Tribuna are a string of newer town houses, said Jeff Schwartz, the administrator at condominiums, and apartment com the 348-patient Edison Estates Re plexes bordered by strip malls. habilitation and Convalescent Center on “It’s a strange little area,” Eisenhower Brunswick Avenue. NEIGHBORHOODS Drive resident Betty Ryan said. “The growth has been good for the “There’s a very quick change, visually, economy and property values are up. It’s driving up here from Route 27.” nice---- The area has developed but not distinctly different and more modern “There’s this older, typically quaint, overdeveloped,” Schwartz said. -

CBSE Board Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper – 1 SA II

CBSE IX | ENGLISH Sample Paper – 1 CBSE Board Class IX English Language and Literature Sample Paper – 1 SA II Maximum Marks: 70 Time – 3 hours The question paper is divided into the following sections. Section A: Reading 20 marks Section B: Writing & Grammar 25 marks Section C: Literature 25 marks SECTION A (READING - 20 marks) Q1. Read the following passage carefully: [8] Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed over 1,200 things including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. Edison is the fourth most prolific inventor in history. He is credited with numerous inventions that contributed to mass communication and, in particular, telecommunications. Edison holds 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as many patents in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. His inventions included a stock ticker, a mechanical vote recorder, a battery for an electric car, electrical power, recorded music and motion pictures. Thomas Edison was born in Milan, Ohio, on 11 February 1847. He went to school for only three months officially, since according to his teachers, his mind often wandered. His mother, who was a school teacher, taught him at home. Thus, Thomas was mostly self- educated. Edison did not invent the first electric light bulb, but instead invented the first commercially practical incandescent light. In 1878, Edison formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Edison made the first public demonstration of his incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. -

Building Stories a Creative Writing Contest for Students (Grades 3-12)

Building Stories A creative writing contest for students (grades 3-12) thehenryford.org/buildingstories 1 Thomas Edison Building Stories A creative writing contest Foundational Materials As you create your story for The Henry Ford’s Building Stories: A Creative Writing Contest, use these foundational materials as a starting point. You can and should conduct additional independent research. Be sure to cite your sources in your bibliography. Table of Contents Section 1 – Edison’s Youth 3 Section 2 – The Wizard of Menlo Park 6 Section 3 – Beyond Menlo Park 12 Section 4 – Edison’s Family and Friends 16 All sources in this document are from the collections of The Henry Ford®. For more information on Building Stories: A Creative Writing Contest, please visit: www.thehenryford.org/BuildingStories thehenryford.org/buildingstories 2 Section 1 Edison’s Youth thehenryford.org/buildingstories 3 Source Daguerreotype of Thomas Edison as a Child, 1851 1 Thomas Edison was born on February 11, 1847, to former schoolteacher Nancy Elliot Edison and Samuel Edison, Jr. who ran a shingle mill and grain business in Milan, Ohio. Thomas was the couple’s seventh and last child (three older siblings died in early childhood). This daguerreotype, which was an early photograph printed on a silver surface, was taken around age 4 and is the first known portrait of the future inventor. Portrait of Thomas Edison as a Teenager, circa 1865 Source 2 A ruddy Thomas Edison sat for this portrait around age 14, while he was working on the Grand Trunk Western Railway. Edison sold popular newspapers and magazines, cigars, vegetables and candy to passengers traveling between his hometown of Port Huron and Detroit, Michigan. -

Explaining Creativity: the Science of Human Innovation/R

EXPLAINING CREATIVITY This page intentionally left blank Explaining Creativity The Science of Human Innovation R. Keith Sawyer 1 2006 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sawyer, R. Keith (Robert Keith) Explaining creativity: the science of human innovation/R. Keith Sawyer p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 978-0-19-516164-9; 978-0-19-530445-9 (pbk.) ISBN 0-19-516164-5; 0-19-530445–4 (pbk.) 1. Creative ability. I. Title BF408.S284 2006 153.3'5—dc 22 2005012982 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been studying and teaching creativity for more than ten years, and have published several academic books on the topic. But when you write a book like this one, summarizing an entire field for the interested general reader, it’s like learning the material all over again. -

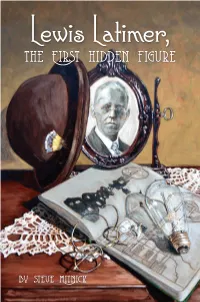

Lewis Latimer, the First Hidden Figure

Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure by steve Mitnick Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure Also by Steve Mitnick Lines Down How We Pay, Use, Value Grid Electricity Amid the Storm Lewis Latimer, The First Hidden Figure By Steve Mitnick Public Utilities Fortnightly Lines Up, Inc. Arlington, Virginia © 2021 Lines Up, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. The digital version of this publication may be freely shared in its full and final format. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947176 Author: Steve Mitnick Editor: Lori Burkhart Assistant Editor: Angela Hawkinson Production: Mike Eacott Cover Design: Paul Kjellander Illustrations: Dennis Auth For information, contact: Lines Up, Inc. 3033 Wilson Blvd Suite 700 Arlington, VA 22201 First Printing, October 2020 V. 1.02 ISBN 978-1-7360142-0-2 Printed in the United States of America. To my boyhood heroes Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Elston Howard and Al Downing The cover painting entitled “Hidden in Bright Light,” is by Paul Kjellander, the President of the Idaho Public Utilities Commission and President of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, commonly referred to by its acronym NARUC. Table of Contents A Word of Inspiration by David Owens ................................ ix Sponsoring this Book and the PUF Latimer Scholarship Fund ............... xii Acknowledgements .............................................. xviii Note to Readers .................................................. xix Foreword ...................................................... xxiv Introduction ...................................................... 1 Chapter 1. The First Hidden Figure .............................. 7 First, and Alone .......................................... -

Beehives Invention

BEEHIVES vy INVENTION Edison and His Laboratories BEEHIVES OF INVENTION Edison and His Laboratories by George E. Davidson National Park Service History Series Office of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1973 Library of Congress catalog card number: 73-600079 CONTENTS Folk Hero 1 An Obsession to Create 7 Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs 13 He Made Science Serve 63 Postscript:The Edison Sites 67 Further Readings 69 OLK HERO He hated the radio; he called it a "lemon." He had even less use for the electronic phonograph. In 1925 he sounded the death knell for the Edison name in the home phonograph industry by saying he would stick with his mechanical device. After much stubborn hesitation, his company brought out an electronic phonograph in 1928. But it was too late. In 1929 the Edison company stopped manu facturing entertainment phonographs and records. A last-minute venture into the mushrooming radio field failed soon afterwards. Thomas Alva Edison belonged to the 19th cen tury. It was there, in the beginnings of America's love affair with technology, that the dynamic and sharp-tongued "country boy" from Milan, Ohio, put his extraordinary genius to work and achieved na tional fame. In that age before the horseless carriage and wireless Thomas Edison made his remarkable contribution to the quality of life in America and became a folk hero, much like an Horatio Alger character. Edison's reputation stayed with him in the early 20th century, but his pace of achievements slack ened. At his laboratory in West Orange, N.J., in the 1900's he did not produce as many important in ventions as he had there and at his Menlo Park, N.J., lab in the late 1800's. -

Thomas Edison's Tracker Organ by J

Volume XIX Number 4 Summer 1975 Thomas Edison's Tracker Organ by J. Paul Schneider Thomas A. Edison and laboratory staff, second floor, Menlo Park New Jersey, February 22, 1880, with original Hllborne Roosevelt organ. Edison seated front row, left of center, cap on head, handB in lap. Photograph from the Collections of Greenfield Vlllage and the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan. W.i.th each visi.t to the second floor of the re part this organ played dur.ing the inventive drama stored Thomas A. Edison Menlo Park Laboratory at which occurred ,in the Menlo Park Laboratory. The Henry Ford's Greenfield V.i.llage [near Detroit, Mich organ was a gift to Edison ,by Hilborne Roosevelt, an igan, J I am intrigued to see the small tracker organ inventor and organ .builder, active in telephone re at one end of the room in the midst of the labora search. Roosevelt greatly admired Edison and pre tory equipment once used by the "Wizard of Menlo sented the instrument ,to him to aid in his sound and Park." telephone experiments. The organ proved to fulf,ill other functions as when 'in Mr. Edison's opinion, In Francis Jehl's book,l Menlo Park Reminis Music's magic strains were needed to soothe the sav cences, the author makes several references .to the age breasts of his employees.' Mr. Jehl continues, "After I began to work here (in the Laboratory), I took part in many a midnight song fest around this lFrancis Jehl was staff laboratory assistant of Thomas Alva Edison at Menlo Park and later the curator of instrument. -

Finding Aid for the Thomas A. Edison Collection, 1860-1980

Finding Aid for THOMAS A. EDISON COLLECTION, 1860-1980, BULK 1860-1950 Accession 1630 Finding Aid Published: January 2012 Electronic conversion of this finding aid was funded by a grant from the Detroit Area Library Network (DALNET) http://www.dalnet.lib.mi.us 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Thomas A. Edison collection Accession 1630 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 1630 CREATOR: Benson Ford Research Center TITLE: Thomas A. Edison collection INCLUSIVE DATES: 1860-1980 BULK DATES: 1860-1950 QUANTITY: 53.6 cubic ft., 50 oversize boxes and 5 volumes LANGUAGE: The materials are in English ABSTRACT: Thomas A. Edison was a great American inventor, applying for 1,093 patents during his lifetime. The collection includes correspondence, drawings, notes, financial records, artifacts, photographs and negatives concerning his work, family, associates and relationship with Henry Ford. Page 2 of 107 Thomas A. Edison collection Accession 1630 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research. Use of original audio or visual materials will require production of digital copies for use in the reading room; interested researchers should contact Benson Ford Research Center staff in advance at [email protected] COPYRIGHT: Copyright has been transferred to The Henry Ford by the donor. Copyright for some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator(s). ACQUISITION: Various donations and purchases RELATED MATERIAL: Related material held by The Henry Ford: - Greenfield Village Buildings records collection, Accession 186 - Edison Institute photographs, Accession 1929 PREFERRED CITATION: Item, folder, box, accession 1630, Thomas A. -

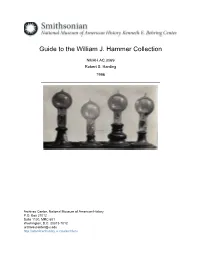

Guide to the William J. Hammer Collection

Guide to the William J. Hammer Collection NMAH.AC.0069 Robert S. Harding 1996 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biography of William J. Hammer..................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 5 'Electrical Diablerie'.......................................................................................................... 5 Expositions and Exhibitions............................................................................................. 8 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 10 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 12 Series 1: William J. Hammer Papers, 1851-1957.................................................. 12 Series 2: Edisonia, 1847-1960.............................................................................. -

Thomas Edison Thomas Edison Often Said That Chemistry Was Late a Chemistry Set; at One Time It Consisted of His Favorite Subject

NOT TO BE TAKEN August 31, 1990 — ME REVIEW - A t-HUNI LIBRART Edison temple to celebrate 30th anniversary in 1991 ■ C/4lcAnEdison Ti«r\ Twp. Pllh Pub. I LibraryihfAfV ^ Edison Twp. Pub. Library 340 Plainiisld Ave. Edison, N.J. 08817 340 Plaimield Ave. Before present synagogue was built, on. N.J. 08817 congregation met in church building By David C. Sheehan went from a handful of pro grew from 75 to more than 175 EDISON — There is a verse spective members to a congre families, and Fellowship Hall in the Book of Exodus which gation with hill High Holiday became inadequate to serve reads, “and let them make me services. the needs of Temple Emanu- a sanctuary that I may dwell St Stephen’s Evangelical El. among them.” Lutheran Church in the Clara Thus, the congregation pur To many Edison residents, Barton section of the township chased the now-unused St this was something more than made its Fellowship Hall Stephen’s Lutheran Church. a passage from the Old Testa available to Temple Emanu-El St Stephen’s, too, had out ment It posed a challenge and for its services and, thus, on grown its Pleasant Avenue an opportunity to form Edi August 25, 1961, Temple Em building and built its current son’s first Reform synagogue. anu-El held its first service. church building near Grand —Photo by Thomas R. DeCaro This challenge was taken up view Avenue. by seven area families who In attendance were the Rev. Construction of Temple Emanu-El, located on James Street across from John F. -

Thomas Edison 1 Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison 1 Thomas Edison Thomas Edison "Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration." – Thomas Alva Edison, Harper's Monthly (September 1932) Born Thomas Alva EdisonFebruary 11, 1847Milan, Ohio, United States Died October 18, 1931 (aged 84)West Orange, New Jersey, United States Occupation Inventor, scientist, businessman Religion Deist Spouse Mary Stilwell (m. 1871–1884) Mina Miller (m. 1886–1931) Children Marion Estelle Edison (1873–1965) Thomas Alva Edison Jr. (1876–1935) William Leslie Edison (1878–1937) Madeleine Edison (1888–1979) Charles Edison (1890–1969) Theodore Miller Edison (1898–1992) Parents Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr. (1804–1896) Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810–1871) Relatives Lewis Miller (father-in-law) Signature Thomas Edison 2 Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931) was an American inventor, scientist, and businessman who developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. Dubbed "The Wizard of Menlo Park" (now Edison, New Jersey) by a newspaper reporter, he was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of mass production and large teamwork to the process of invention, and therefore is often credited with the creation of the first industrial research laboratory.[1] Birthplace of Thomas Edison Edison is considered one of the most prolific inventors in history, holding 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as many patents in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. He is credited with numerous inventions that contributed to mass communication and, in particular, telecommunications. These included a stock ticker, a mechanical vote recorder, a battery for an electric car, electrical power, recorded music and motion pictures.