Position Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

War of Words: Isan Redshirt Activists and Discourses of Thai Democracy

This is a repository copy of War of words: Isan redshirt activists and discourses of Thai democracy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/104378/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Alexander, ST and McCargo, D orcid.org/0000-0002-4352-5734 (2016) War of words: Isan redshirt activists and discourses of Thai democracy. South East Asia Research, 24 (2). pp. 222-241. ISSN 0967-828X https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X16649045 © 2016, SOAS. This is an author produced version of a paper published in South East Asia Research. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ War of Words War of Words: Isan Redshirt Activists and Discourses of Thai Democracy Abstract Thai grassroots activists known as ‘redshirts’ (broadly aligned with former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra) have been characterized accordingly to their socio-economic profile, but despite pioneering works such as Buchanan (2013), Cohen (2012) and Uenaldi (2014), there is still much to learn about how ordinary redshirts voice their political stances. -

Download This PDF File

“PM STANDS ON HIS CRIPPLED LEGITINACY“ Wandah Waenawea CONCEPTS Political legitimacy:1 The foundation of such governmental power as is exercised both with a consciousness on the government’s part that it has a right to govern and with some recognition by the governed of that right. Political power:2 Is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labor, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. Demonstration:3 Is a form of nonviolent action by groups of people in favor of a political or other cause, normally consisting of walking in a march and a meeting (rally) to hear speakers. Actions such as blockades and sit-ins may also be referred to as demonstrations. A political rally or protest Red shirt: The term5inology and the symbol of protester (The government of Abbhisit Wejjajiva). 1 Sternberger, Dolf “Legitimacy” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (ed. D.L. Sills) Vol. 9 (p. 244) New York: Macmillan, 1968 2 I.C. MacMillan (1978) Strategy Formulation: political concepts, St Paul, MN, West Publishing; 3 Oxford English Dictionary Volume 1 | Number 1 | January-June 2013 15 Yellow shirt: The terminology and the symbol of protester (The government of Thaksin Shinawat). Political crisis:4 Is any unstable and dangerous social situation regarding economic, military, personal, political, or societal affairs, especially one involving an impending abrupt change. More loosely, it is a term meaning ‘a testing time’ or ‘emergency event. CHAPTER I A. Background Since 2008, there has been an ongoing political crisis in Thailand in form of a conflict between thePeople’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the People’s Power Party (PPP) governments of Prime Ministers Samak Sundaravej and Somchai Wongsawat, respectively, and later between the Democrat Party government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD). -

The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 6 The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Thai and U.S. Army Soldiers participate in Cobra Gold 2006, a combined annual joint training exercise involving the United States, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. Photo by Efren Lopez, U.S. Air Force The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics By Zachary Abuza Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 Series Editors: C. Nicholas Rostow and Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

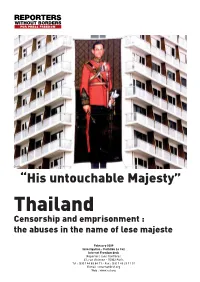

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

Love, Anger and Hate of the Red Shirts: the Contestation of Meanings of Politics and Justice

Volume 20 No 2 (July-December) 2017 [Page 103-124] Love, Anger and Hate of the Red Shirts: The Contestation of Meanings of Politics and Justice Thannapat Jarenpanit * Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Thailand Received 15 October 2017; Received in revised form 28 January 2018 Accepted 4 February 2018; Available online 7 March 2018 Abstract This article focuses on the cultural emotions of the red shirt supporters after the contexts of military coup in 2006. The patterns of emotions seen within the red shirt groups can help reveal their internal differences, and also the divisions and conflicts that exist there in. I will examine this issue by focusing on an analysis of the affective emotions of love (a positive emotion), anger and hate (negative emotions) displayed by the red shirt groups from Chiang Mai and Bangkok. These emotions can reflect the contestation of meanings of politics, democracy and justice among the social sub-groups and individuals who joined the red shirt protests during the last decade of Thailand’ s political conflicts. This situation, containing different cultural emotions and political meanings, has led to a deeply divided Thai population in terms of the country’s politics and society. To understand the diversity of social characteristics and actions that exist within the red shirt groups, one cannot see emotions as static; as emotions vary in terms of their meanings, levels and dynamics, based on the contexts and cultures within which they are experienced. Keywords Cultural emotions, Contestation, The red shirts, Politics, Justice * Corresponding author: [email protected] DOI: 10.14456/tureview.2017.12 Jarenpanit, T. -

Political Demonology, Dehumanization, and Contemporary Thai Politics

Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 19(2) 2019, pp. 115–130 RESEARCH ARTICLE Political Demonology, Dehumanization, and Contemporary Thai Politics Siwach Sripokangkul1* and Mark S. Cogan2 1Khon Kaen University, Thailand 2Kansai Gaidai University, Japan [email protected] Abstract: The employment of acts of political demonology has become common among power holders in Thai society. Demonization campaigns trace back to the early 1970s when Thai nationalists deemed Communists to be “beasts in human clothing.” This paper reviews demonization strategies employed by power holders (countersubversives) to undermine, marginalize, and repress anti-government protesters (subversives), beginning with the formative 1970s student movements, and continuing through the 2014 military coup d’état. We argue through a series of vignettes that the Thai elites have conveniently labeled anti-government protesters and their mobilization networks as demons, trolls, or animals due to their supposed threats to the Thai state, its monarchy, or national religion. Keywords: political demonology, Thailand, dehumanization, state violence, repression Demonology, or regarding others as non-human Although demonology has been accredited with or as being unwelcome, is a phenomenon that has origins in the United States because of Rogin’s been around as long as political society itself. The work, there are oft-cited examples elsewhere, such political variety is primarily derived from Michael as the Nazi dissemination of a massive ideological Rogin’s (1987) book, “Ronald Reagan, The Movie dehumanization of a host of other groups of people, and Other Episodes in Political Demonology, which devaluing these groups as lower forms of life, called to the attention the creation of monsters as a commonly associated with animals (Steizinger, 2018). -

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the Publication of the White Paper on Surrogacy in 2015, There Have Been Addit

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the publication of the white paper on surrogacy in 2015, there have been additional cases of concern as well as some legal developments. While surrogacy has become increasingly lauded due to its use by celebrities, its troubling aspects continue to receive short shrift in media and culture. This addendum to that paper provides some updates and examples related to laws, cases, and surrogacy stories which have emerged that raise highlight the risks and problems associated with the practice. Examples of changes in laws related to surrogacy Due to concerns about surrogacy tourism and exploitation, India took steps to limit its surrogacy industry in 2018. The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2016 banned commercial surrogacy and prohibited foreigners from contracting with surrogates.1 Under the law’s provisions, surrogates must be a close relative and may only be reimbursed for medical expenses, in hopes of ensuring that vulnerable poor women are not exploited.2 The law also restricted altruistic surrogacy to infertile, married heterosexual couples.3 As of 2020, the legislature was considering some changes to the law based on recommendations from a committee, such as allowing divorced or widowed women access to surrogacy, removing the requirement that a surrogate be a close relative, and removing the five year infertility requirement.4 Turkey had already prohibited surrogacy, but has sought to strengthen its rules, including criminal penalties. A 2017 report noted that the Health Ministry proposed -

Thailand After the Red Shirt Uprising

Avoiding Conflict: Thailand after the Red Shirt Uprising Thailand’s 2006 coup unleashed deadly political conflict as a conservative elite rallied against Thaksin Shinawatra and his red shirt supporters. Further strife was predicted in the wake of Yingluck Shinawatra’s 2011 election victory. But, as Kevin Hewison reports, the expected clashes have not yet materialised. n April and May 2010, Thailand’s reducing opposition from the mili- challenge their own hierarchical con- colour-coded political conflicts tary, judiciary and monarchy. trol of the state. Igrabbed international attention While some in the red shirt Soon after Thaksin’s victory, these when the governing Democrat Party movement considered the election opponents began a campaign to oust led by Abhisit Vejjajiva ordered army a mandate for rapid and progressive him. The yellow-shirted People’s Al- crackdowns on pro-Thaksin Shina- change, for Thaksin, Yingluck and liance for Democracy (PAD) rallied watra red shirt protesters that were Pheu Thai leaders, compromise and and demonstrated, destabilising the demanding a new election. The reconciliation have been the defin- government. With Thaksin refusing result was more than 90 killed and ing political strategies since gaining to resign, the military was prodded some 2,400 injured. In murky cir- office. The underlying rationale for into action, prompted by former cumstances, several areas of Bang- all this has been a determination that generals in the king’s advisory kok and some provincial capitals the Yingluck administration should body, the Privy Council. When the were torched. Abhisit had presided remain in place for a full term and More than 90 military’s tanks rolled and the king over a remarkable expansion of po- gain re-election.