Vint, Allan Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNI -News Feb 11

February 11 ! CNI Belfast Cathedral girl chorister records at St Paul’s ! Tania Murphy, a member of the Cathedral Girls’ Choir, has recently returned to St Paul’s Cathedral, London, to record a CD with St Paul's Cathedral Choir and choristers from other UK cathedrals. The Diamond Fund for Choristers CD will be released on March 17. This Fund was launched last April at a concert in St Paul’s to mark the Friends of Cathedral Music’s diamond jubilee. The concert brought together choristers [email protected] Page !1 February 11 representing 60 cathedrals along with the choir of St Paul’s for the first time ever Tania was selected by St Anne’s Master of the Choristers David Stevens to represent the Cathedral at the concert in St Paul’s on April 27 last year. The concert was presented by Classic FM’s Aled Jones and Alexander Armstrong, and held in the presence of HRH The Duchess of Gloucester. After her visit to St Paul’s, Tania said she had formed new friendships with choristers from different parts of the country who shared the same interests, and described it as ‘definitely an experience which I will never forget!’ Tania has sung with the St Anne’s Choir for almost four years. “I love being a chorister of St Anne's Cathedral as I have always been intrigued by the concept of choral music and the resonating sound of the music in such a big cathedral as St Anne's,” she said. “Being a chorister has given me so many opportunities such as singing in Puccini's opera Turandot, singing with the St Anne's choir on a tour of Paris, and of course this wonderful opportunity of being able to sing in St Paul's Cathedral, London.” [email protected] Page !2 February 11 ! Social Action Award for Armagh Church Lads' and Church Girls' Brigade Members of St Saviour’s, Dobbin, and St Aidan’s, Grange, Companies, both from Armagh Diocese, were at Buckingham Palace recently to receive a Social Action Award from the Prince of Wales. -

History of the Rise, Progress, Genius, and Character

v A HISTORY JAN 22 1932 &+*. A fo L SFVA^ OF THE RISE, PROGRESS, GENIUS, AND CHARACTER OF AMERICAN PRESRYTERIANISIfl: TOGETHSB WITH A REVIEW OF "THE CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OP THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, BY CHAS. HODGE, D. D. PROFESSOR IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, AT PRINCETON, N. J." BY WILLIAM HILL, D. D. OF WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA. WASHINGTON CITY: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BT J. GIDEON, jn. 1839. 1 Entered according to the Act of Congress, on the fourteenth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and thirty-nine, by Jacob Gideojj, jr. in the Clerk's office of the District Court for the District of Columbia. — CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Reference to the present divided state of the Presbyterian Church—The loose and un- guarded manner in which Professor Hodge uses the term Presbyterian—The trua meaning of the terms Puritan and Presbyterian—Quotation from Dr. Miller upon th« subject—Professor Hodge claims the majority of the Puritans in England, and of the Pilgrims who first settled New England, as good Presbyterians, and as agreeing with the strict Scotch system—What the Scotch system of strict Presbyterianism is The Presbyterianism of Holland—The Presbyterianism of the French Protestants Professor Hodge's misrepresentation of them corrected by a quotation from Neal's History ; also, from Mosheim and others—The character of the English Presbyte- rians—The true character of the Puritans who settled New England—The kind of Church Government they introduced among them—The Cambridge Platform Quotations from it—Professor Hodge's misunderstanding of it—The Saybrook Plat- form also misrepresented —Cotton Mather's account of the first Presbyterians in New England misrepresented by Professor Hodge—Dr. -

Monday 10 November 2014 Bishop Ted Luscombe Celebrates His 90Th Birthday Today

Monday 10 November 2014 Bishop Ted Luscombe celebrates his 90th Birthday today. Bishop Ted was Bishop of Brechin 1975-90 and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church 1985-90. He ordained our current Bishop Nigel as Deacon and Priest in St Paul’s Cathedral Dundee 1976/77. Sunday 23 November 2014 Bishop Nigel will be Licencing the Reverend Tracy Dowling as Chaplain (Assistant Curate) of St Paul’s Cathedral Dundee at the 11am Cathedral Eucharist for the Feast of Christ the King, together with Carole Spink who will be Admitted and Licenced as a Reader. Tracy comes from the Merton Priory Team Ministry in south London after a career with HMRC. Carole is completing her training at the Scottish Episcopal Institute and will also serve at the Cathedral. Tuesday 25 November 2014 The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is making a visit to the Dundee Centre of Mission St Luke’s Downfield, Dundee on Tuesday morning. The Centre, launched this September, is a partnership between the Diocese and Church Army, aiming to pioneer fresh ways of doing church for the unchurched. The Archbishop will meet local people connected with the project, Craig Dowling, Pioneer Evangelist and the Reverend Kerry Dixon, Priest Missioner. Bishop Nigel will welcome the Archbishop to our diocese and the Primus, Bishop David Chillingworth who is hosting the Archbishop during his visit to the Scottish Episcopal Church. Friday 28 November 2014 Bishop Nigel is attending the Abertay University winter Graduation Ceremony in the Caird Hall Dundee in his capacity as a Governor and Member of the University Court. -

Cover 65 3&4.Pmd

EVENTEENTH- ENTURY EWS FALL - WINTER 2007 Vol. 65 Nos. 3&4 Including THE NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 55, Nos. 3&4 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS VOLUME 65, Nos. 3&4 FALL-WINTER, 2007 SCN, an official organ of the Milton Society of America and of the Milton Section of the Modern Language Association, is published as a double issue two times each year with the support of the English Departments of: University of Akron Oklahoma State University Texas A&M University SUBMISSIONS: As a scholarly review journal, SCN publishes only commis- sioned reviews. As a service to the scholarly community, SCN also publishes news items. A current style sheet, previous volumes’ Tables of Contents, and other information all may be obtained via our home page on the World Wide Web. Books for review and queries should be sent to: Prof. Donald R. Dickson English Department 4227 Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843-4227 E-Mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www-english.tamu.edu/pubs/scn/ ISSN 0037-3028 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS EDITOR DONALD R. DICKSON Texas A&M University ASSOCIATE EDITORS James Egan, University of Akron Jeffrey Walker, Oklahoma State University Michele Marrapodi, University of Palermo Patricia Garcia, Our Lady of the Lake University E. Joe Johnson, Clayton State University EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Mark A. Houston, Texas A&M University Jacob A. Tootalian, Texas A&M University CONTENTS VOLUME 65, NOS. 3&4 ......................... FALL-WINTER, 2007 REVIEWS Harold Love, English Clandestine Satire, 1660-1702. Review by MARGARET J.M. EZELL ............................................................................. 105 Anthony Adolph, Full of Soup and Gold: The Life of Henry Jermyn. -

Diocese in Europe Prayer Diary, July to December 2011

DIOCESE IN EUROPE PRAYER DIARY, JULY TO DECEMBER 2011 This calendar has been compiled to help us to pray together for one another and for our common concerns. Each chaplaincy, with the communities it serves, is remembered in prayer once a year, according to the following pattern: Eastern Archdeaconry - January, February Archdeaconry of France - March, April Archdeaconry of Gibraltar - May, June Diocesan Staff - July Italy & Malta Archdeaconry - July Archdeaconry of North West Europe - August, September Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe Nordic and Baltic Deanery - September, October Germany - November Swiss Archdeaconry - November, December Each Archdeaconry, with its Archdeacon, is remembered on a Sunday. On the other Sundays, we pray for subjects which affect all of us (e.g. reconciliation, on Remembrance Sunday), or which have local applications for most of us (e.g. the local cathedral or cathedrals). Some chaplains might like to include prayers for the other chaplaincies in their deanery. We also include the Anglican Cycle of Prayer (daily, www.aco.org), the World Council of Churches prayer cycle (weekly, www.oikoumene.org, prayer resources on site), the Porvoo Cycle (weekly, www.porvoochurches.org), and festivals and commemorations from the Common Worship Lectionary (www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts.aspx). Sundays and Festivals, printed in bold type, have special readings in the Common Worship Lectionary. Lesser Festivals, printed in normal type, have collects in the Common Worship Lectionary. Commemorations, printed in italics, may have collects in Exciting Holiness, and additional, non- biblical, readings for all of these may be found in Celebrating the Saints (both SCM-Canterbury Press). -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Bishop Says Scottish Church’S Move on Gay Marriage ‘A Way Forward’

Page 1! CNI ! DUP MP says gay rights will be maintained in Tory-DUP deal A Democratic Unionist Party member has said that LGBT rights would be maintained if they formed a coalition party with the Conservatives despite his party’s stance on same-sex marriage. Jim Shannon, a Christian who was re-elected as the MP for Strangford said he had heard comments made by gay Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson who said she had received www.churchnewsireland.org NEWS June 12 Page 2! assurances from the Prime Minister over gay rights if a deal between the parties was made. He said despite people's concerns, the party during negotiations wants to set conditions that will "benefit everyone across the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland". He added: "We want to ensure that every one of the LGBT community have rights and their rights will be maintained. So, there's going to be no changes to that whatsoever. "The situation in Northern Ireland is very different. The Northern Ireland Assembly will make those decisions - they're two diverse and different opinions. Bishop says Scottish church’s move on gay marriage ‘a way forward’ The Church of Ireland may have found a way forward on the issue of same-sex marriage following a move by a church in Scotand, Bishop of Cork Paul Colton has said, Ratsy McGarry reports in the Irish Times. The Scottish Episcopal Church last week became the first major church in Britain or www.churchnewsireland.org NEWS June 12 Page 3! # ! Church of Ireland Bishop of Cork Paul Colton: ‘the reality is that there is such diversity and di"erence throughout the Church of Ireland.’ Ireland to allow same-sex marriage. -

Chaplaincy in a New Scottish University: the Issue Ofworship I

T Chaplaincy in a New Scottish University: The Issue ofWorship Christine M. Goldie "'r' The Starting Point I. My starting point is my experience as chaplain at Glasgow Polytechnic, later Glasgow Caledonian University, a post to which I was appointed in March 1992. I had previously served as the minister of St Cuthbert's Church in Clydebank, having been ordained to the ministry and inducted to that charge in May 1984. Almost as soon as I had been introduced as the first full-time chaplain to the Polytechnic, I began to sense uncertainties in my role. In retrospect, I believe I was actually fairly certain of my role. The Polytechnic authorities, however, saw my role differently, and the Church of Scotland, as whose minister I went to the Polytechnic, by virtue of my ordination (even if the Church was paying only a small proportion of my salary), differently again. Two early experiences, one of which occurred almost right away, and the second taking place a year after the first, helped me to realise that these uncertainties, or tensions, focused on my role as a worship leader. In particular, awkward negotiations prior to two quite different worship events - both involving the university administration and church authorities - convinced me that these tensions were connected to complex problems related to structure and theology, which in turn were connected to the different expectations of university and church. At the beginning of my study for the Doctor of Ministry degree in 1996, I was still wrestling with the problem of worship in the university setting, for it had become a problem, at least for me. -

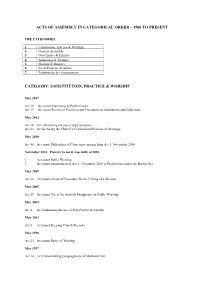

Acts of Assembly in Categorical Order – 1980 to Present

ACTS OF ASSEMBLY IN CATEGORICAL ORDER – 1980 TO PRESENT THE CATEGORIES 1. Constitution, Practice & Worship 2. General Assembly 3. Governance & Finance 4. Admission & Training 5. Mission & Ministry 6. Local Property & Assets 7. Presbyteries & Congregations CATEGORY: CONSTITUTION, PRACTICE & WORSHIP May 2017 Act 18 Act anent Reprinting of Psalm Books Act 19 Act anent Review of Practices and Procedures at Ordinations and Inductions May 2012 Act 16 Act authorising the use of Sing Scripture Act 22 Act declaring the Church’s Confessional Position on Marriage May 2010 Act 48 Act anent Difficulties of Conscience arising from Act 1, November 2010 November 2010 Plenary General Assembly of 2010 1. Act anent Public Worship 2. Act anent transmission of Act 1, November 2010 to Presbyteries under the Barrier Act May 2009 Act 30 Act anent review of Procedure for the Calling of a Minister May 2005 Act 29 Act anent Use of the Scottish Paraphrases in Public Worship May 2003 Act 4 Act authorising the use of Sing Psalms in worship May 2002 Act 5 Act anent Keeping Church Records May 1998 Act 24 Act anent Purity of Worship May 1997 Act 14 Act Consolidating Congregations of Mull and Coll May 1996 Act 16 Act anent Eligibility for Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2 1985, Section 4) Act 17 Act anent Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2, 1985, Section 4) Act 24 Act anent Procedures in relation to Calls May 1994 Act 8 Act anent The Practice – Supplement to Chapter on Discipline May 1992 Act 6 Act anent Supplementary Versions of the Psalms May -

Melrose: the Church and Parish of S

Melrose: The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert 19 Melrose : The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert ON the soil of Melrose Christian worship has been offered up for fully thirteen hundred years. The congregation of Melrose S. Cuthbert's Parish Church can thus trace its spiritual ancestry throughout that period by links which, if not formal, may justly be described as organic, by way of the Reformation to the famous Cistercian Abbey, and thence to the ancient Celtic monastery at Old Melrose two and a half miles away. The Celtic Monastery : The Monks of S. Cuthbert Old Melrose is little known and still less frequented. On the road between Leaderfoot and Dryburgh at its highest point of vantage, now known as " Scott's View ", Sir Walter was accustomed to halt, both to rest his horses and himself to enjoy the romantic landscape. From that point one looks across Tweed to a broad tongue of land almost enclosed by a loop of the river, with the Eildon Hills behind sheltering the place from the prevailing south-west winds. This tongue of land is Old Melrose. Here in the early part of the seventh century the Celtic monastery was founded, reputedly by S. Aidan of Iona himself, and quite surely at his instance, with a colony of monks deriving from Columba's own monastery. Here also Cuthbert, Celtic " Apostle of the Borders ", Roman Bishop of Hexham, anchorite of Lindisfarne and saint, entered on his novitiate. It is recorded by the Rev. Adam Milne, a minister of the parish during the first half of the eighteenth century, that in his day stones of the enclosing cincture of the monastery were still to be seen above ground. -

Allan Downie Lesley Sangster Rachel Mullan Jasmine Neufeld

SCR Rachel Mullan In September 2015, Rachel made the long On the pastoral side, Rachel was a tutor in journey across the Irish Sea to join us in the Home House and was very good at keeping Maths department at Glenalmond. Fresh out a lively bunch of girls on track, helping guide of university, she was full of enthusiasm them towards a successful set of A Level and new ideas and quickly threw herself results. into life at Coll. She is an excellent Beyond teaching, Rachel became involved in mathematician and a great teacher. musical productions, lacrosse coaching, Duke Rachel taught a full range of pupils, from the of Edinburgh, Third Form activities and camps, young Third Form intake to the slightly older contributing hugely to life at Glenalmond. hands in Upper Sixth and will be sorely missed We all wish her the very best as she moves by all the pupils she taught. on to take up her new post at Merchiston in Edinburgh. Gareth O’Neill Lesley Sangster Lesley Sangster is a staff nurse at People drink rain water but, during dry seasons, Glenalmond College. During Easter 2017 use the dirty lake for all forms of washing and Lesley volunteered her medical services on toileting. There is no facility to boil water. a much-needed hospital ship in Tanzania. We sailed to three different islands; Iroba, Here, she tells us about her vital work… Ihumbo & Bumbire, providing vital healthcare to hundreds of patients every day. In total, we I have just returned from a two week mission, treated 4,038 patients; 2,624 were GP, dental volunteering on-board the ‘Jubilee Hope’ medical and optician visits, the rest received healthcare ship, sailing around the ‘Forgotten’ Islands on advice. -

The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow

Servants to St. Mungo: The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow by Daniel MacLeod A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Daniel MacLeod, May, 2013 ABSTRACT SERVANTS TO ST MUNGO: THE CHURCH IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY GLASGOW Daniel MacLeod Advisors: University of Guelph, 2013 Dr. Elizabeth Ewan Dr. Peter Goddard This thesis investigates religious life in Glasgow, Scotland in the sixteenth century. As the first full length study of the town’s Christian community in this period, this thesis makes use of the extant Church documents to examine how Glaswegians experienced Christianity during the century in which religious change was experienced by many communities in Western Europe. This project includes research from both before and after 1560, the year of the Reformation Parliament in Scotland, and therefore eschews traditional divisions used in studies of this kind that tend to view 1560 as a major rupture for Scotland’s religious community. Instead, this study reveals the complex relationships between continuity and change in Glasgow, showing a vibrant Christian community in the early part of the century and a changed but similarly vibrant community at the century’s end. This project attempts to understand Glasgow’s religious community holistically. It investigates the institutional structures of the Church through its priests and bishops as well as the popular devotions of its parishioners. It includes examinations of the sacraments, Church discipline, excommunication and religious ritual, among other Christian phenomena. The dissertation follows many of these elements from their medieval Catholic roots through to their Reformed Protestant derivations in the latter part of the century, showing considerable links between the traditions.