Vietnam: a Soldier's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soldiers and Veterans Against the War

Vietnam Generation Volume 2 Number 1 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Article 1 Against the War 1-1990 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1990) "GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol2/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GI RESISTANCE: S o l d ie r s a n d V e t e r a n s AGAINST THE WAR Victim am Generation Vietnam Generation was founded in 1988 to promote and encourage interdisciplinary study of the Vietnam War era and the Vietnam War generation. The journal is published by Vietnam Generation, Inc., a nonprofit corporation devoted to promoting scholarship on recent history and contemporary issues. ViETNAM G en eratio n , In c . ViCE-pRESidENT PRESidENT SECRETARY, TREASURER Herman Beavers Kali Tal Cindy Fuchs Vietnam G eneration Te c HnIc a I A s s is t a n c e EdiTOR: Kali Tal Lawrence E. Hunter AdvisoRy BoARd NANCY ANISFIELD MICHAEL KLEIN RUTH ROSEN Champlain College University of Ulster UC Davis KEVIN BOWEN GABRIEL KOLKO WILLIAM J. SEARLE William Joiner Center York University Eastern Illinois University University of Massachusetts JACQUELINE LAWSON JAMES C. -

Cobia Database Articles Final Revision 2.0, 2-1-2017

Revision 2.0 (2/1/2017) University of Miami Article TITLE DESCRIPTION AUTHORS SOURCE YEAR TOPICS Number Habitat 1 Gasterosteus canadus Linné [Latin] [No Abstract Available - First known description of cobia morphology in Carolina habitat by D. Garden.] Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturæ, ed. 12, vol. 1, 491 1766 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) Ichthyologie, vol. 10, Iconibus ex 2 Scomber niger Bloch [No Abstract Available - Description and alternative nomenclature of cobia.] Bloch, M. E. 1793 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) illustratum. Berlin. p . 48 The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the Under this head was to be carried on the study of the useful aquatic animals and plants of the country, as well as of seals, whales, tmtles, fishes, lobsters, crabs, oysters, clams, etc., sponges, and marine plants aml inorganic products of U.S. Commission on Fisheries, Washington, 3 United States. Section 1: Natural history of Goode, G.B. 1884 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) the sea with reference to (A) geographical distribution, (B) size, (C) abundance, (D) migrations and movements, (E) food and rate of growth, (F) mode of reproduction, (G) economic value and uses. D.C., 895 p. useful aquatic animals Notes on the occurrence of a young crab- Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 4 eater (Elecate canada), from the lower [No Abstract Available - A description of cobia in the lower Hudson Eiver.] Fisher, A.K. 1891 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) 13, 195 Hudson Valley, New York The nomenclature of Rachicentron or Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum Habitat 5 Elacate, a genus of acanthopterygian The universally accepted name Elucate must unfortunately be supplanted by one entirely unknown to fame, overlooked by all naturalists, and found in no nomenclator. -

Exclusif : Mariluon En Studio !

EXCLUSIF : MARILUON EN STUDIO ! MANOWAR SATRIANI MOONSPELL RAMMSTEIN SOULFLY, le nouveau groupe de Max Cavalera GOTTHARD ARENA RÉFÉRENDUM 97 L 6915-24-27,00 F-RD * r * T ^l i 5 1 •' i R * ; L ■ ^ H « i l B f p |> - 0 IW m T r \ 3^T > T „J IM &DAY £ ~ -J‘r- ,T f n T 'i |- ;. <. .n«i«~ > —r- • j a l g ^ i _ '.________~ n i n /. _ je hll~!Sz \1 K*îfTCcî cil Celuilogucî gi'cliliiî: c 'l l r % } M tSBËM â&kJUiteiirt^y-ittpi/AwAv.ifl-nel. ffl/wwsoa (r^M) Concept sur un thème de Science-Fiction Chronique inteîl&geinte*.. 'r ir iB l£v\£>\ï,Ç* ÉDiro kouJ# L e 11 mars dernier l r%n ''la'ra- 'î 'iî 'i a z’if tz à Paris de son nouve. - et e<ce..e"t : a’..eLY3 - album «Virtual XI». Et a :a nc!e à Steve H a rri s ne fait jamais es :':ses ::~ ^ e .as autres, un matcn de 'oct ru: c'ca^sé a_ stade Je Rungis. Il opposa une équ’ce a^iç.a'sa c:»p:see de plusieurs membres du grCupe :e 'cares et : an ciens internat’onaux br’ta^^iq_e5 _c " z " z ’\, Wo::- f f l s v w s i s c v cock ex-Manojneste' . à _',e at-'oe z'.~' co p a a i s laque..e :\q l .a : 'è~e ;es j : _ 5 s -•= à •: :< cz&stiB’VM : çais ains; c-e = : sta's V t :e ’ ■ " : sa Deilae. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Newsletter Still Doesn't Have Any Reporting on Direct Queries and Submissions To: Recent Developments in U.S

N ewsletter NoVEMbER, 1991 VolUME 5 NuMbER 5 SpEciAl JournaL Issue In This Issue................................................................ 2 The Speed of DAnksess ancI "CrazecJ V ets on tHe oorstep rama e o s e PublJshER's S tatement, by Ka U TaL .............................5 D D ," by DAvId J. D R ...............40 REMF Books, by DAvid WHLs o n .............................. 45 A nnouncements, Notices, & Re p o r t s ......................... 4 eter C ortez In DarIen, by ALan FarreU ........................... 22 PoETRy, by P D ssy............................................4 4 FIctIon: Hie Romance of Vietnam, VoIces fROM tHe Past: TTie SearcTi foR Hanoi HannaK by RENNy ChRlsTophER...................................... 24 by Don NortTi ...................................................44 A FiREbAlL In tBe Nlqlrr, by WHUam M. KiNq...........25 H ollyw ood CoNfidENTlAl: 1, b y FREd GARdNER........ 50 Topics foR VJetnamese-U.S. C ooperation, PoETRy, by DennIs FRiTziNqER................................... 57 by Tran Qoock VuoNq....................................... 27 Ths A ll CWnese M ercenary BAskETbAll Tournament, Science FIctIon: This TIme It's War, by PauI OLim a r t ................................................ 57 by ALascIaIr SpARk.............................................29 (Not Much of a) War Story, by Norman LanquIst ...59 M y Last War, by Ernest Spen cer ............................50 Poetry, by Norman LanquIs t ...................................60 M etaphor ancI War, by GEORqE LAkoff....................52 A notBer -

University of Cape Town

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Lost Soldiers from Lost Wars: A Comparative Study of the Collective Experience of Soldiers of the Vietnam War and the Angoran/Namibian Border War by Gretchen Bourland Rudham BRLGRE002 Town Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts inCape English (American Studies) of Department of English Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town University2003 This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people, has,.,bee!l pttributed, and has been cited and referenced. Jr~ 3. ~c.Y~ignature Lost Soldiers from Lost Wars: A Comparative Study of the Collective Experience of Soldiers of the Vietnam War and the Angolan/Namibian Border War I explore the Vietnam War and the Border War of South Africa through the analysis of the oral histories of the soldiers who fought in these wars. Considering the scarcity of oral histories about the Border War, I conducted several personal interviews with Border War soldiers to add to the oral histories representing that conflict. -

Luther Lee Sanders '64 1 Luther Lee Sanders '64

Honoring….. Honoring…LUTHER LEE SANDERS '64 1 LUTHER LEE SANDERS '64 Captain, United States Army Presidential Unit Citation Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry 1st Cav Div 101st Abn Div 1965 ‐ 1966 1969 th 3 Bn 187 Para Inf “Rakkasans” While at Texas A&M... Before Texas A&M... When anyone uses the term “Son of the Service”, In September 1960, Lee Sanders travelled from think of Luther Lee Sanders. Lee was born in Colo- Vacaville, California to College Station where he en- rado Springs, spent his childhood in several places rolled as an Agricultural Economics major. Back then, around the world, and attended three different high Army cadets who were students in the College of Agri- schools before graduating from Vacaville High culture were assigned to Company D-1 or “Spider D”. School, just outside Travis AFB, California. A few weeks into our Fish Year, Lee was one of several At an early age, Lee learned the value and hundred who tried-out for the Fish Drill Team. Lee cer- importance of non-commissioned officers tainly knew how to do Drill and Ceremonies. When the in any organization – especially when it selection process eliminated most of the hundreds who comes to maintaining “good order and tried, Lee was one of the 44 freshmen selected. From discipline”. Lee’s father was a Chief Mas- that point forward until Mother’s Day, Fish Drill Team ter Sergeant in the U. S. Air Force. was a big part of Lee’s effort. In fact, it was Master Sergeant Sanders who aimed Lee toward Texas A&M at an early age. -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

2011 01 Newsletter Printer Final

January 2011 The Currahee! The Newsletter of the 506th Airborne Infantry Regiment Association (Airmobile — Air Assault) We Stand Together – then, now, and always Hill 996, A Shau Valley, July 10, 1969 1st Lt. Leonard “Len“ Griffin 2/319th Artillery, 101st Airborne Division Forward Observer to D Company, 1/506th, Vietnam 1969 On July 11, 1969, on a nondescript mountain top vived Hill 996 told our medic Rick “Doc” Daniels, ʺNo numbered 996 near Hamburger Hill in the A Shau Valley one will ever know what happened here.ʺ Seventeen of Vietnam, the 1/506th Infantry and other units engaged a days later Sgt Denton died in a mortar attack. I swore, if I larger NVA force. The day before, the forward observer could, I would take up Sgt. Denton’s challenge and tell for D 1/506th was injured jumping out of a helicopter on the story. When I decided to face my demons of Viet‐ the air assault. I was called and told to replace him and nam, I had to face Hill 996. Thanks to enormous support that is how I got involved with the men of the 506th and of those who were there with me, I made it. th Hill 996. By the end of the day on the 11 , 20 Americans I felt the men who didn’t walk off the Hill should had been killed and 26 wounded. Eight Silver Stars were be remembered and honored to some degree. Living awarded to the men and one Medal of Honor to SPC. near Toccoa, Georgia, the Mecca of the 101st Airborne Gordon Roberts who survived the war. -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

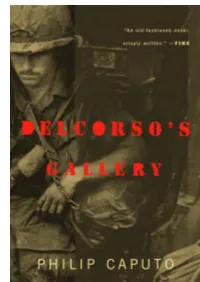

Download Delcorso's Gallery, Philip Caputo, Random House LLC, 2012

DelCorso's Gallery, Philip Caputo, Random House LLC, 2012, 0307822052, 9780307822055, 368 pages. A classic novel of Vietnam and its aftermath from Philip Caputo, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir A Rumor of War is widely considered among the best ever written about the experience of war.At thirty-three, Nick DelCorso is an award-winning war photographer who has seen action and dodged bullets all over the world–most notably in Vietnam, where he served as an Army photographer and recorded combat scenes whose horrors have not yet faded in his memory. When he is called back to Vietnam on assignment during a North Vietnamese attempt to take Saigon, he is faced with a defining choice: should he honor the commitment he has made to his wife not to place himself in any more danger for the sake of his career, or follow his ambition back to the war-torn land that still haunts his dreams? What follows is a riveting story of war on two fronts, Saigon and Beirut, that will test DelCorso’s faith not only in himself, but in the nobler instincts of men.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1j0zXiV Acts of Faith , Philip Caputo, May 3, 2005, Fiction, 669 pages. Philip Caputo’s tragic and epically ambitious new novel is set in Sudan, where war is a permanent condition. Into this desolate theater come aid workers, missionaries, and .... Dispatches , Michael Herr, 2009, History, 247 pages. Written on the front lines in Vietnam, "Dispatches" became an immediate classic of war reportage when it was published in 1977. -

Филмð¾ð³ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑ)

Dulé Hill Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Twenty Five https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twenty-five-7857786/actors Full Disclosure https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/full-disclosure-5508031/actors Five Votes Down https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/five-votes-down-5456181/actors Two Cathedrals https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/two-cathedrals-8770451/actors The Crackpots and These https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-crackpots-and-these-women-7727929/actors Women Let Bartlet Be Bartlet https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/let-bartlet-be-bartlet-6532644/actors An Khe https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/an-khe-4750131/actors Manchester (Part I) https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/manchester-%28part-i%29-6747478/actors The Lame Duck Congress https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lame-duck-congress-7745291/actors The Short List https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-short-list-7763978/actors The Warfare of Genghis https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-warfare-of-genghis-khan-7773548/actors Khan Ways and Means https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ways-and-means-5810871/actors Memorial Day https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/memorial-day-6815397/actors On the Day Before https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/on-the-day-before-609025/actors The Drop-In https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-drop-in-5473760/actors Separation of Powers https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/separation-of-powers-5680809/actors Access https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/access-4672407/actors