University Micrdfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plano De Los Transportes Del Distrito De Usera

AEROPUERTO T4 C-1 CHAMARTÍN C-2 EL ESCORIAL C-3 ALCOBENDAS-SAN. SEB. REYES/COLMENAR VIEJO C-4 PRÍNCIPE PÍO C-7 FUENTE DE LA MORAN801 C-7 VILLALBA-EL ESCORIAL/CERCEDILLAN805 C-8 VILLALBA C-10 Plano de los transportes delN806 distrito de Usera Corrala Calle Julián COLONIA ATOCHA 36 41 C1 3 5 ALAMEDA DE OSUNA Calle Ribera M1 SEVILLA MONCLOA M1 SEVILLA 351 352 353 AVDA. FELIPE II 152 C1 CIRCULAR PAVONES 32 PZA. MANUEL 143 CIRCULAR 138 PZA. ESPAÑA ÓPERA 25 MANZANARES 60 60 3 36 41 E1 PINAR DE 1 6 336 148 C Centro de Arte C s C 19 PZA. DE CATALUÑA BECERRA 50 C-1 PRÍNCIPE PÍO 18 DIEGO DE LEÓN 56 156 Calle PTA. DEL SOL . Embajadores e 27 CHAMARTÍN C2 CIRCULAR 35 n Reina Sofía J 331 N301 N302 138 a a A D B E o G H I Athos 62 i C1 N401 32 Centro CIRCULAR N16 l is l l t l F 119 o v 337 l PRÍNCIPE PÍO 62 N26 14 o C-7 C2 S e 32 Conde e o PRÍNCIPE PÍO P e Atocha Renfe C2 t 17 l r 63 K 32 a C F d E P PMesón de v 59 N9 Calle Cobos de Segovia C2 Comercial eña de CIRCULAR d e 23 a Calle 351 352 353 n r lv 50 r r EMBAJADORES Calle 138 ALUCHE ú i Jardín Avenida del Mediterráneo 6 333 332 N9 p M ancia e e e N402 de Casal 334 S a COLONIA 5 C1 32 a C-10 VILLALBA Puerta M1 1 Paseo e lle S V 26 tin 339 all M1 a ris Plaza S C Tropical C. -

INSIDE the U.S

Vol. XII, No. 5 www.cubatradenews.com May 2010 Ag debate shifts to privatizing distribution radually moving the focus of reform Selling debate from state decentralization to potatoes part-privatization,G private farmers at a three- in Trinidad, day congress of the National Association of Cuba Small Farmers (ANAP) blamed the state for bottlenecks in food production and distribution in Cuba, and — while not using the p-word — proposed more privatization of distribution. Photo: Rosino, Wikimedia Photo: Rosino, In a 37-point resolution, the organization representing some 362,000 private farmers supports the expansion of suburban agriculture with direct distribution to Also see: city outlets, and suggests allowing the Opinion direct sale of cattle to slaughterhouses page 3 by cooperatives, direct farm sales to the tourist sector, and that the state promote and support farm-based micro-processing plants for local crops, whose products should be freely sold on markets. Private farmers — ranging from small landowners leasing state land to cooperative Cont’d on page 5 U.S. grants Cuba travel license to Houston-based oil group he International Association of Drilling Contractors Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control rejected IADC’s received a travel license from the U.S. Department of first license application in December. Al Fox and the group TreasuryT May 19, allowing the Houston-based group to send appealed and reapplied in March; OFAC granted the license a delegation to Cuba within three months, Tampa lobbyist and Continued on next page businessman Al Fox told Cuba Trade & Investment News. This marks the first time a U.S. -

JOHN ASHBERY Arquivo

SELECTED POEMS ALSO BY JOHN ASHBERY Poetry SOME TREES THE TENNIS COURT OATH RIVERS AND MOUNTAINS THE DOUBLE DREAM OF SPRING THREE POEMS THE VERMONT NOTEBOOK SELF-PORTRAIT IN A CONVEX MIRROR HOUSEBOAT DAYS AS WE KNOW SHADOW TRAIN A WAVE Fiction A NEST OF NINNIES (with James Schuyler) Plays THREE PLAYS SELECTED POEMS JOHN ASHBERY ELISABt'Tlf SIFTON BOOKS VIKING ELISABETH SIYrON BOOKS . VIKING Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Limited, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada UR IB4 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Copyright © John Ashbery, 1985 All rights reserved First published in 1985 by Viking Penguin Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada Page 349 constitutes an extension ofthis copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Ashbery, John. Selected poems. "Elisabeth Sifton books." Includes index. I. Title. PS350l.S475M 1985 811'.54 85-40549 ISBN 0-670-80917-9 Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Ilarrisonburg, Virginia Set in Janson Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means· (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission ofboth the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. CONTENTS From SOME TREES Two Scenes 3 Popular Songs 4 The Instruction Manual 5 The Grapevine 9 A Boy 10 ( ;Iazunoviana II The Picture of Little J. -

Hispano Cubana

revista 15 índice 6/10/03 12:02 Página 1 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 15 Invierno 2003 Madrid Enero-Abril 2003 revista 15 índice 6/10/03 12:02 Página 2 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Javier Martínez-Corbalán REDACCIÓN Celia Ferrero Orlando Fondevila Begoña Martínez CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Alina Fernández, Mª Victoria Fernández-Ávila, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Guillermo Gortázar Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, César Leante, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Julio San Francisco, Juan Morán, Eusebio Mujal-León, Fabio Murrieta, Mario Parajón, José Luis Prieto Benavent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Rafael Solano, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es Esta revista es miembro de ARCE miembro de la Asociación de Federación Revistas Culturales Iberoamericana de de España Revistas Culturales (FIRC) EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.com Suscripciones: España: 24 Euros al año. Otros países: 58 Euros al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 8 Euros. Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO, -

Informe Buenas Prácticas De Comunicación Hipermedia En

BUENAS PRÁCTICAS DE Instituto Internacional de Periodismo COMUNICACIÓN José Martí, 2020 Lisandra Gómez, Ernesto Guerra, Sabdiel Batista, Itsván Ojeda, HIPERMEDIA EN TIEMPOS Manuel Alejandro Romero, Patricia Alonso Galbán y Dixie Edith Trinquete DE COVID-19 Informe de resultados I. El periodismo en tiempos de SARS-CoV-2: a modo de introducción ....................................... 2 II. El desafío, la muestra y la ruta metodológica ......................................................................... 3 La muestra ................................................................................................................................. 5 Tipología de medios .............................................................................................................. 5 Canal de publicación y medios más representados .............................................................. 5 Colaboración autoral ............................................................................................................. 7 Recursos multimediales ........................................................................................................ 7 Co-ocurrencia de términos .................................................................................................... 8 A modo de resumen: generalizaciones de la muestra .......................................................... 8 III. Resultados generales a partir de la integración de los criterios de selección y análisis ....... 9 Regularidades detectadas tras el análisis de los indicadores: -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

3 Villaverde Alto - Moncloa

De 6:00 de la mañana a 1:30 de la madrugada / From 6:00 a.m. to 1:30 a.m. Intervalo medio entre trenes / Average time between trains Línea / Line 3 Villaverde Alto - Moncloa Lunes a jueves (minutos) Viernes (minutos) Sábados (minutos) Domingos y festivos (minutos) / Period / Period Período Monday to Thursday (minutes) Fridays (minutes) Saturdays (minutes) Sundays & public holidays (minutes) Período 6:05 - 7:00 3 ½ - 6 3 ½ - 6 7 - 9 7 - 9 6:05 - 7:00 7:00 - 7:30 2 ½ - 3 ½ 2 ½ - 3 ½ 7:00 - 7:30 7 - 8 7:30 - 9:00 7:30 - 9:00 2 - 3 2 - 3 7 - 8 9:00 - 9:30 9:00 - 9:30 9:30 - 10:00 9:30 - 10:00 3 - 4 3 - 4 6 - 7 10:00 - 11:00 10:00 - 11:00 11:00 - 14:00 4 - 5 4 - 5 5 ½ - 6 ½ 11:00 - 14:00 14:00 - 17:00 3 - 4 4 ½ - 5 ½ 14:00 - 17:00 3 ½ - 4 ½ 17:00 - 21:00 17:00 - 21:00 3 ½ - 4 ½ 3 ½ - 4 ½ 4 - 5 21:00 - 22:00 5 - 6 21:00 - 22:00 22:00 - 23:00 6 - 7 5 ½ - 6 ½ 5 ½ - 6 ½ 5 ½ - 6 ½ 22:00 - 23:00 23:00 - 0:00 7 ½* 7 ½* 7 ½* 7 ½* 23:00 - 0:00 0:00 - 2:00 15 * 15 * 12 * 15 * 0:00 - 2:00 Nota: Note: Los intervalos medios se mantendrán de acuerdo con este cuadro, salvo incidencias en la línea. Average times will be in accordance with this table, unless there are incidents on the line. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

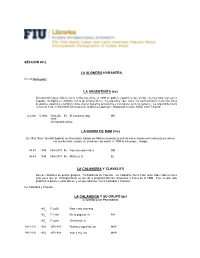

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA.