Tourism, Festivals and Cultural Events in Times of Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEEFHS Journal Volume VII No. 1-2 1999

FEEFHS Quarterly A Journal of Central & Bast European Genealogical Studies FEEFHS Quarterly Volume 7, nos. 1-2 FEEFHS Quarterly Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? Tue Federation of East European Family History Societies Editor: Thomas K. Ecllund. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group Managing Editor: Joseph B. Everett. [email protected] of American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, reli- Contributing Editors: Shon Edwards gious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven Daniel Schlyter societies bad accepted its concept as founding members. Each year Emily Schulz since then FEEFHS has doubled in size. FEEFHS nows represents nearly two hundred organizations as members from twenty-four FEEFHS Executive Council: states, five Canadian provinces, and fourteen countries. lt contin- 1998-1999 FEEFHS officers: ues to grow. President: John D. Movius, c/o FEEFHS (address listed below). About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi-pur- [email protected] pose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 1st Vice-president: Duncan Gardiner, C.G., 12961 Lake Ave., ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, on-line services, in- Lakewood, OH 44107-1533. [email protected] stitutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and 2nd Vice-president: Laura Hanowski, c/o Saskatchewan Genealogi- other ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes or- cal Society, P.0. Box 1894, Regina, SK, Canada S4P 3EI ganizations representing all East or Central European groups that [email protected] have existing genealogy societies in North America and a growing 3rd Vice-president: Blanche Krbechek, 2041 Orkla Drive, group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from Minneapolis, MN 55427-3429. -

LÚR Festival

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Hagnýt menningarmiðlun LÚR festival Greinagerð um menningarviðburðinn LÚR festival: Listahátíð Lengst Útí Rassgati Greinagerð til MA-prófs í Hagnýtri menningarmiðlun Ólöf Dómhildur Jóhannsdóttir Kt.: 170281-4119 Leiðbeinandi: Sigurjón B. Hafsteinsson September 2015 ÁGRIP Greinargerð þessi er hluti af af lokaverkefni mínu í hagnýtri menningarmiðlun við Háskóla Íslands og fjallar um vinnsluferli miðlunarhluta verkefnisins og fræðilegra þátta. Miðlunarleiðin sem valin var er listahátíð sem ber nafnið „LÚR-festival“ með undirtitilinn „Listahátíð lengst útí rassgati“. Hátíðin er menningarhátíð ungmenna haldin í fyrsta sinn sumarið 2014 og í annað sinn sumarið 2015. Undirbúningur hátíðarinnar er stór hluti verkefnisins og er greint frá vinnuferlinu frá upphafi til enda og eru bæði verklegir og fræðilegir þættir teknir fyrir. Ég vil tileinka verkefnið öllum þeim ungmennum sem hafa áhuga á listum og menningu sem nær út fyrir hátíðarhöld sautjánda júní og annarra hefðbundinna hátíða. 1 Efnisyfirlit 1 Inngangur .................................................................................................................... 4 2 Farvegur lista og menningar ......................................................................................... 5 3 Samhengið ................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Hvað er hátíð? .................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Fyrir -

Wings Without Borders Alas Sin Fronteras IV North American Ornithological Conference IV Congreso Norteamericano De Ornitología

Wings Without Borders Alas Sin Fronteras IV North American Ornithological Conference IV Congreso Norteamericano de Ornitología October 3-7, 2006 · 3-7 Octubre 2006 Veracruz, México CONFERENCE PROGRAM PROGRAMA DEL CONGRESO IV NAOC is organized jointly by the American Ornithologists’ Union, Association of Field Ornithologists, Sección Mexicana de Consejo Internacional para la Preservación de las Aves, A. C., Cooper Ornithological Society, Raptor Research Foundation, Society of Canadian Ornithologists / Société des Ornithologistes du Canada, Waterbird Society, and Wilson Ornithological Society 4to. Congreso Norteamericano de Ornitología - Alas Sin Fronteras Programa del Congreso Table of Contents IV NAOC Conference Committees ......................................................................................................................................................................................2 Local Hosts ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 Conference Sponsors .............................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Other Sponsors ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Ca' Foscari Short Film Festival 7

Short ca’ foscari short film festival 7 1 15 - 18 MARZO 2017 AUDITORIUM SANTA MARGHERITA - VENEZIA INDICE CONTENTS × Michele Bugliesi Saluti del Rettore, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia × Michele Bugliesi Greetings from the Rector, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Flavio Gregori Saluti del Prorettore alle attività e rapporti culturali, × Flavio Gregori Greetings from the Vice Rector for Cultural activities and relationships, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Board × Board × Ringraziamenti × Acknowledgements × Comitato Scientifico × Scientific Board × Giuria Internazionale × International Jury × Catherine Breillat × Catherine Breillat × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Barry Purves × Barry Purves × Giuria Levi Colonna Sonora × Levi Soundtrack Jury × Concorso Internazionale × International Competition × Concorso Istituti Superiori Veneto × Veneto High Schools’ Competition × Premi e menzioni speciali × Prizes and special awards × Programmi Speciali × Special programs × Concorso Music Video × Music Video Competition × Il mondo di Giorgio Carpinteri × The World of Giorgio Carpinteri × Desiderio in movimento - Tentazioni di celluloide × Desire on the move - Celluloid temptations × Film making all’Università Waseda × Film-making at Waseda University Waseda Students Waseda Students Il mondo di Hiroshi Takahashi The World of Hiroshi Takahashi × Workshop: Anymation × Workshop: Anymation × Il mondo di Iimen Masako × The World of Iimen Masako × C’era una volta… la Svizzera × Once upon a time… Switzerland -

Open'er Festival

SHORTLISTED NOMINEES FOR THE EUROPEAN FESTIVAL AWARDS 2019 UNVEILED GET YOUR TICKET NOW With the 11th edition of the European Festival Awards set to take place on January 15th in Groningen, The Netherlands, we’re announcing the shortlists for 14 of the ceremony’s categories. Over 350’000 votes have been cast for the 2019 European Festival Awards in the main public categories. We’d like to extend a huge thank you to all of those who applied, voted, and otherwise participated in the Awards this year. Tickets for the Award Ceremony at De Oosterpoort in Groningen, The Netherlands are already going fast. There are two different ticket options: Premium tickets are priced at €100, and include: • Access to the cocktail hour with drinks from 06.00pm – 06.45pm • Three-course sit down Dinner with drinks at 07.00pm – 09.00pm • A seat at a table at the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm • Access to the after-show party at 00.00am – 02.00am – Venue TBD Tribune tickets are priced at €30 and include access to the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm (no meal or extras included). Buy Tickets Now without further ado, here are the shortlists: The Brand Activation Award Presented by: EMAC Lowlands (The Netherlands) & Rabobank (Brasserie 2050) Open’er Festival (Poland) & Netflix (Stranger Things) Øya Festivalen (Norway) & Fortum (The Green Rider) Sziget Festival (Hungary) & IBIS (IBIS Music) Untold (Romania) & KFC (Haunted Camping) We Love Green (France) & Back Market (Back Market x We Love Green Circular) European Festival Awards, c/o YOUROPE, Heiligkreuzstr. -

485 Svilicic.Vp

Coll. Antropol. 37 (2013) 4: 1327–1338 Original scientific paper The Popularization of the Ethnological Documentary Film at the Beginning of the 21st Century Nik{a Svili~i}1 and Zlatko Vida~kovi}2 1 Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia 2 University of Zagreb, Academy of Dramatic Art, Zagreb, Croatia ABSTRACT This paper seeks to explain the reasons for the rising popularity of the ethnological documentary genre in all its forms, emphasizing its correlation with contemporary social events or trends. The paper presents the origins and the de- velopment of the ethnological documentary film in the anthropological domain. Special attention is given to the most in- fluential documentaries of the last decade, dealing with politics: (Fahrenheit 9/1, Bush’s Brain), gun control (Bowling for Columbine), health (Sicko), the economy (Capitalism: A Love Story), ecology An Inconvenient Truth) and food (Super Size Me). The paper further analyzes the popularization of the documentary film in Croatia, the most watched Croatian documentaries in theatres, and the most controversial Croatian documentaries. It determines the structure and methods in the making of a documentary film, presents the basic types of scripts for a documentary film, and points out the differ- ences between scripts for a documentary and a feature film. Finally, the paper questions the possibility of capturing the whole truth and whether some documentaries, such as the Croatian classics: A Little Village Performance and Green Love, are documentaries at all. Key words: documentary film, anthropological topics, script, ethnographic film, methods, production, Croatian doc- umentaries Introduction This paper deals with the phenomenon of the popu- the same time, creating a work of art. -

Filming in Croatia 2020 1 Filming in Croatia 2020

Filming in Croatia 2020 1 Filming in Croatia 2020 Production Guide cover photo: Game of Thrones s8, Helen Sloan/hbo, courtesy of Embassy Films 2 Filming in Croatia 2020 Contents Introduction · 4 Permits and Equipment · 94 Location Permits · 97 Filming in Croatia · 8 Shooting with Unmanned Aircraft The Incentive Programme · 12 Systems (drones) · 99 Selective Co-Production Funding · 20 Visas · 102 Testimonials · 24 Work Permits for Foreign Nationals · 103 Customs Regulations · 105 Local Film Commissions · 38 Temporary Import of Professional Equipment · 107 Locations · 46 Country at a Glance · 50 Made in Croatia · 108 Istria · 52 Kvarner and the Highlands · 56 Dalmatia · 60 Slavonia · 64 Central Croatia · 68 Crews and Services · 72 Production Know-How · 75 Production Companies · 80 Crews · 81 Facilities and Technical Equipment · 83 Costumes and Props · 85 Hotels and Amenities · 88 Airports and Sea Transport · 89 Buses and Railways · 91 Traffic and Roads · 93 Zagreb, J. Duval, Zagreb Tourist Board Filming in Croatia 2020 5 Introduction Star Wars: The Last Jedi, John Wilson/Lucasfilm © 2018 Lucasfilm Ltd. All Rights Reserved Croatia offers an ideal combination Dubrovnik as the setting for King’s Landing, the fortress of Klis as the city of Meereen, and locations in Šibenik and Kaštilac of filming conditions. It is a small, for the city of Braavos. Numerous locations throughout Croatia hosted the bbc One’s McMafia, awarded best drama series at yet diverse country, with breath- the International Emmy Awards. hbo’s Succession season 2 taking locations; its landscapes finale took the luxurious cruise down the Dalmatian coast before scoring Golden Globe for Best Television Series – Drama. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

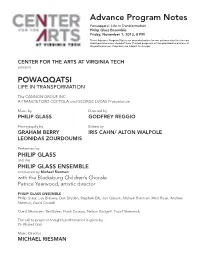

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

VIPNEWSPREMIUM > VOLUME 146 > APRIL 2012

11 12 6 14 4 4 VIPNEWS PREMIUM > VOLUME 146 > APRIL 2012 3 6 10 8 1910 16 25 9 2 VIPNEWS > APRIL 2012 McGowan’s Musings It’s been pouring with rain here for the last below normal levels. As the festival season weather! Still the events themselves do get couple of days, but it seems that it’s not the looms and the situation continues, we may covered in the News you’ll be glad to know. right type of rain, or there’s not enough of see our increasingly ‘green’ events having it because we are still officially in drought. to consider contingency plans to deal with I was very taken by the Neil McCormick River levels across England and Wales are the water shortages and yet more problems report in UK newspaper The Telegraph from lowest they’ve been for 36 years, since our caused by increasingly erratic weather. I’m the Coachella festival in California, as he last severe drought in 1976, with, according sure that many in other countries who still wrote, “The hairs went up on the back of my to the Environmental Agency, two-thirds picture England as a rain swept country neck…” as he watched the live performance ‘exceptionally ’ low, and most reservoirs where everybody carries umbrellas will find of Tupac Shakur…” This is perfectly it strange to see us indulging in rain dances understandable , as unfortunately, and not to over the next couple of months! put too fine a point on it, Tupac is actually dead. His apparently very realistic appearance Since the last issue of VIP News I have was made possible by the application of new journeyed to Canada, Estonia and Paris, and holographic projection technology. -

The Case Study of Apocalypto

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288187016 Relativism, Revisionism, Aboriginalism, and Emic/Etic Truth: The Case Study of Apocalypto Article · August 2013 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1065-2-8 CITATIONS READS 2 2,540 1 author: Richard D Hansen University of Utah 33 PUBLICATIONS 650 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Mirador Basin Project, Guatemala View project Mirador Basin Archaeological Project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Richard D Hansen on 30 March 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Chapter 8 Relativism, Revisionism, Aboriginalism, and Emic/Etic Truth: The Case Study of Apocalypto Richard D. Hansen Abstract Popular fi lm depictions of varied cultures, ranging from the Chinese, Africans, and Native Americans have repeatedly provided a variant perception of the culture. In works of fi ction, this fl aw cannot only provide us with entertainment, but with insights and motives in the ideological, social, or economic agendas of the authors and/or directors as well as those of the critics. Mel Gibson’s Maya epic Apocalypto has provided an interesting case study depicting indigenous warfare, environmental degradation, and ritual violence, characteristics that have been derived from multidisciplinary research, ethnohistoric studies, and other historical and archaeological investigations. The fi lm received extraordinary attention from the public, both as positive feedback and negative criticism from a wide range of observ- ers. Thus, the elements of truth, public perception, relativism, revisionism, and emic/etic perspectives coalesced into a case where truth, fi ction, and the virtues and vices of the authors and director of the fi lm as well as those of critics were exposed.