Namibia and the United Nations Until 1990 Dennis U Zaire*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Windhoek, Namibia Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Windhoek, Namibia Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA NAMIBIA Population: 2,533,224 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 1.91% (2018) Median Age: 21.4 GDP: USD$29.6 billion (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita: USD$11,200 (2017 est.) City of Intervention: Windhoek Urban Population: 50% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.2% annual rate of change (2015- 2020 est.) Land Area: 910,768 sq km Total Roadways: 48,327 km (2014) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi-Scalar Governance Following a 25-year war, Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 under the rule of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Since then, SWAPO has held the presidency, prime minister’s office, the national assembly, and most local and regional councils by a large majority. While opposition parties are active (there are over ten groups), they remain weak and fragmented, with most significant political differences negotiated within SWAPO. The constitution and other legislation dating to the early 1990s emphasize the role of regional and local councils – and since 1998, the government has been engaged in efforts to support decentralization of power.1 However, all levels are connected by SWAPO (through common membership), so power remains effectively centralized. -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

Episcopalciiuriimen

EPISCOPALCIIURIIMEN soUru VAFR[CA Room 1005 * 853 Broadway, New York, N . Y. 10003 • Phone : (212) 477-0066 , —For A free Southern Afilcu ' May 1982 MISSIONS MOVEMENTS NAMIBIA 'The U .S. 'overnment has become an agent in South Africa's "holy crusade" against Communism . ' - The Rev Dr Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the Council of Churches in Namibia, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 25 April 1982. It was a . mission of frustration and a harsh learning experience . Four Namibian churchmen made a month-long visit to Western nations to express their feelings about the unending, agonizing occupation of their country by the South African regime and the fruitless talks on a Namibian settlement which the .Western Contact Group - the USA, Britain, France ,West Germany and Canada - has staged for five long years . Anglican Bishop James Kauluma, presi- dent of the Council of Churches in Namibia ; Bishop Kleopas Du neni of the Evangelical Luth- eran Ovambokavango Church ; Pastor Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the CCN ;, and the, assistant to Bishop D,mmeni, Pastor Absalom Hasheela, were accompanied by a representative of the South African Council of Churches and the general secretary of the All Africa Coun- cil of Oburches which sponsored the trip . They visited France, Sweden, Britain and Canada, end terminated their journey in the United States . It was here that the Namibian pilgrims encountered the steely disregard for Namibian aspirations by functionaries of a major power mapped up in its geopolitical stratagems. They met with Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester .Crocker, whose time is primarily devoted to pursuing the mirage of a Pretorian agreement to the United Nations settlement plan for Namibia . -

Civil Supremacy of the Military in Namibia: an Evolutionary Perspective

~f Civil Supremacy of the Military in Namibia: An Evolutionary Perspective By Guy Lamb Department of Political Studies University of Cape Town December 1998 Town Cape of . ·-~\,1.~ l ~ -._/ I /- -....,,._,.,---, University r/ / ~ This dissertation is for the partial fulfillment for a Master of Social Sciences (International and Comparative Politics). The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Town Cape of University Table of Contents Page Abstract i Maps ii Acknowledgements VI List of Acronyms viI Introduction 1 Civil Supremacy in Namibia: An Evolution? 1 Civil Supremacy and its Importance 2 Focus on Namibia 4 · Why Namibia? 5 Chapter 1: The Historical Evolution of Civil Supremacy: A 6 Conceptual Approach Town 1.1 Introducing the Problem 6 1.2 Civil-Military Relations: Survey of the Discipline and 7 Review of the Literature Cape 1.2.1 Civil-Military Relations as a Field of Study 7 1.2.2 Review of Civil Military Relationsof Literature 8 1.2.3 Focus on Civil Supremacy 11 1.3 What is Civil Supremacy? 12 1.3.1 An Overview of Civil Supremacy 12 1.3.2 A Question of Bias 13 1.4 Civil Military Traditions 14 1.4.1 Colonial 14 1.4.2 Revolutionary/Insurgent 15 1.4.2.1 The InfluenceUniversity of Mao Tse-tung -

Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: Genocide and the Quest of Recompense Gewald, J.B.; Jones A

Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: genocide and the quest of recompense Gewald, J.B.; Jones A. Citation Gewald, J. B. (2004). Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: genocide and the quest of recompense. In Genocide, war crimes and the West: history and complicity (pp. 59-77). London: Zed Books. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4853 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4853 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: Genocide and the Quest for Recompense Jan-Bart Gewald On 9 September 2001, the Herero People's Reparations Corporation lodged a claim in a civil court in the US District of Columbia. The claim was directed against the Federal Republic of Germany, in the person of the German foreign minister, Joschka Fischer, for crimes against humanity, slavery, forced labor, violations of international law, and genocide. Ninety-seven years earlier, on n January 1904, in a small and dusty town in central Namibia, the first genocide of the twentieth Century began with the eruption of the Herero—German war.' By the time hostilities ended, the majority of the Herero had been killed, driven off their land, robbed of their cattle, and banished to near-certain death in the sandy wastes of the Omaheke desert. The survivors, mostly women and children, were incarcerated in concentration camps and put to work as forced laborers (Gewald, 1995; 1999: 141—91). Throughout the twenti- eth Century, Herero survivors and their descendants have struggled to gain recognition and compensation for the crime committed against them. -

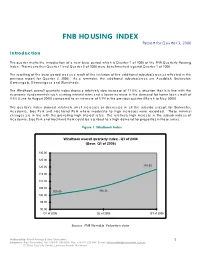

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

Washington, D.C

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIVIL DIVISION THE HERERO PEOPLE’S REPARATIONS CORPORATION, : a District of Columbia Corporation : 1625 K Street, NW, #102 : Washington, D.C. 20006 : : THE HEREROS, : a Tribe and Ethnic and Racial Group, : by and through its Paramount Chief : By Paramount Chief Riruako : Paramount Chief K. Riruako : P.O. Box 60991 Katutura : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Mburumba Getzen Kerina : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Kurundiro Kapuuo : Case No. 01-0004447 Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Judge Jackson Calendar 2 Cornelia Tjaveondja : Next Scheduled Event: P.O. Box 24861 : Initial Scheduling Conference Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : September 18, 2001 at 9:30 a.m. Moses Nguarambuka : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Hilde Kazakoka Kamberipa : SQ66 Genesis Street : P.O. Box 61831 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Festus Korukuve : P.O. Box 50 : Opuuo (Otuzemba), Namibia : Uezuvanjo Tjihavgc : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Ujeuetu Tjihange : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Moses Katuuo : P.O. Box 930 : Gobabis, Namibia 9000 : Levy K. O. Nganjone : P.O. Box 309 : Gobabis, Namibia : Festus Ndjai : Opuuo, Namibia : Hoomajo Jjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Uelembuia Tjinawba : Okandombo : Okunene Region, Namibia : Jararaihe Tjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Hangekaoua Mbinge : Opuuo, Namibia : Ehrens Jeja : Box 210 : Omaruru : Omatjete, Namibia : Nathanael Uakumbua : Box 211 : Omaruru, Namibia : Rudolph Kauzuu : Box 210 : Omatjete : Omaruru, Namibia : 2 Jaendekua Kapika : Opuuo, Namibia : Ben Mbeuserua : P.O. Box 224 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Felix Kokati : Box 47 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Samuel Upendura : Oyinene : Omaheke Region, Namibia : Majoor Festus Kamburona : P.O. 1131 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Uetavera Tjirambi : Okonmgo : Okanene Region, Namibia : Julius Katjingisiua : P.O. -

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES COHP Transcript Mr RF ‘Pik’ Botha: APPENDIX ONE Content: Interview with Mr RF ‘Pik’ Botha conducted by Dr Sue Onslow in Akasia, Pretoria, South Africa on 15th July 2008. Collected as part of research for the Africa International Affairs Programme at the London School of Economics Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy (LSE IDEAS). Key: SO: Sue Onslow (Interviewer) RB: Mr RF ‘Pik’ Botha (Respondent) SO: How far did South Africa find itself isolated and beleaguered in the international community because of SA intervention in Angola in 1975? RB: Under the Alvor Agreement, the three signatories – MPLA, FNLA and UNITA – were to govern Angola together until 11 November 1975. This meant that virtually every ministry and department would have had 3 officials for every post. However, the Portuguese governor gave in – he was pro-communist and favoured the MPLA. This caused disruption inside Angola and brought Cuban intervention, as the MPLA position in the central part of the country was strengthened by large numbers of Cuban troops. Against that background, UNITA requested South African assistance. In the case of Mozambique, the Portuguese handed over power to FRELIMO, the only nationalist movement, in accordance with international law. Hence South Africa immediately recognised the new government and power was transferred regularly. However, we never recognised the new government in Angola because the MPLA had seized power. I was then Ambassador in Washington. The South African view was a fear: where would the Cubans stop? Would they cross into Ovamboland, in northern South West Africa/Namibia? Then there would be a war there, too. -

The Cassinga Massacre of Namibian Exiles in 1978 and the Conflicts Between Survivors’ Memories and Testimonies

ENDURING SUFFERING: THE CASSINGA MASSACRE OF NAMIBIAN EXILES IN 1978 AND THE CONFLICTS BETWEEN SURVIVORS’ MEMORIES AND TESTIMONIES BY VILHO AMUKWAYA SHIGWEDHA A Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of the Western Cape December 2011 Supervisor: Professor Patricia Hayes ABSTRACT During the peak of apartheid, the South African Defence Force (SADF) killed close to a thousand Namibian exiles at Cassinga in southern Angola. This happened on May 4 1978. In recent years, Namibia commemorates this day, nationwide, in remembrance of those killed and disappeared following the Cassinga attack. During each Cassinga anniversary, survivors are modelled into „living testimonies‟ of the Cassinga massacre. Customarily, at every occasion marking this event, a survivor is delegated to unpack, on behalf of other survivors, „memories of Cassinga‟ so that the inexperienced audience understands what happened on that day. Besides survivors‟ testimonies, edited video footage showing, among others, wrecks in the camp, wounded victims laying in hospital beds, an open mass grave with dead bodies, SADF paratroopers purportedly marching in Cassinga is also screened for the audience to witness the agony of that day. Interestingly, the way such presentations are constructed draw challenging questions. For example, how can the visual and oral presentations of the Cassinga violence epitomize actual memories of the Cassinga massacre? How is it possible that such presentations can generate a sense of remembrance against forgetfulness of those who did not experience that traumatic event? When I interviewed a number of survivors (2007 - 2010), they saw no analogy between testimony (visual or oral) and memory. They argued that memory unlike testimony is personal (solid, inexplicable and indescribable). -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek.